Photographers on Photographers: Benjamin Dimmitt on Bridget Conn

For the entire month of August, photographers will be interviewing photographers–image makers who have inspired them, who they are curious about, whose work has impacted them in some way. I am so grateful to all the participants for their efforts, talents, and time. -Aline Smithson

Since moving from New York City to Asheville, NC in 2014, I’ve come to know various local and regional photographers. Asheville is a place where many artists are very attuned to craft and process – an interesting hybrid of the Black Mountain College of Art legacy and the centuries old craft traditions of the southern Appalachians. As a result, I’ve become intrigued by new and different ways to speak photographically.

When considering an artist to interview that I admire, Bridget Conn immediately came to mind. At a time when most artists are working digitally, she uses arcane alternative photographic processes that eschew cameras, lenses, film and all things digital. Her chemigrams are closer to painting and drawing than they are to camera-based photography. She is one of the hardest working artists I know. I love her work and admire her process and commitment. She is very passionate about her practice and I’m always interested to see what she’s doing.

Bridget Conn earned a BFA in Studio Art from Tulane University in 2000, and an MFA from the University of Georgia in 2003, focusing in photography, mixed media and installation. In 2009, Bridget moved to Asheville, NC where she taught at several colleges, in addition to working as an arts writer, designer, and independent artist. Her association with the Phil Mechanic Studios Public Darkroom blossomed into the creation of The Asheville Darkroom, a non-profit art educational facility which she founded in 2012 and served as Executive Director and primary instructor through May 2016. Bridget joined the faculty of Armstrong State University (now Georgia Southern University) in Savannah, GA as Assistant Professor of Art in August 2016, focusing on analog photographic processes. Her current artwork explores the potential of photography as a chemical and physical medium through the process of chemigrams.

Conn will offer a chemigram workshop at the Society for Photographic Education’s Southeast Regional Conference at the Penland School of Crafts in September, as well as present a paper on analog artmaking processes at SECAC in Birmingham, AL in October. Her upcoming exhibitions include shows at Mercer University in Macon GA in November, at Jacksonville State University in Jacksonville AL in March 2019, and at Tracey Morgan Gallery in Asheville NC in the spring of 2019.

Benjamin Dimmitt graduated from Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, FL and also studied at the International Center of Photography in NYC, NY, Santa Fe Photographic Workshop in Santa Fe, NM, Santa Reparata Graphic Arts Centre in Florence, Italy and City and Guild Arts School in London, England.

He moved to New York City after college and held an adjunct professor position at the International Center of Photography from 2001-2013. He now lives and works in Asheville, NC and teaches workshops in the Southeast.

Benjamin’s photographs have been exhibited at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, School of International Center of Photography, NYC, NY, American Academy of Arts & Letters, NYC, NY, Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans, LA and Florida Museum of Photographic Arts, Tampa, FL .

His work is represented by Clayton Galleries in Tampa, FL and is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the Florida Museum of Photographic Arts among others.

Benjamin’s photographs will be included in Asheville’s photo+sphere festival this fall and in a three-person climate change exhibit at the Southeast Museum of Photography next year.

Benjamin Dimmitt: What was growing up like for you?

Bridget Conn: I grew up mostly in Orlando, surrounded by strip malls and concrete, going to Catholic school my whole life and living 10 minutes from Disney. My personal experience growing up in Florida had very little contact with nature, and that became really important for me to experience later in life and through my art. I was a straight-A nerdish kid, later becoming an obnoxious mallrat, eventually turning into a moody kneesock-wearing gothy teenager, who was still interested in making A’s. My known-family at the time was very small and disconnected, so my relationships with friends and music were really important to me. When my mom and I moved to Clearwater to be with my stepdad, leaving everything I loved in Orlando, I rebelled by spending nights alone staring at the ocean, writing bad poetry, and blaring Dead Can Dance out of my car into the salty air. I guess I could have been worse.

BD: What brought you to photography?

BC: I remember the first time I was allowed to use a camera – I was six, and just ran around the house snapping pictures of random things with a point-and-shoot. I still remember getting the film back, and seeing the photo I had taken of whatever was on the television screen at the moment – it had been a picture of a race car. Something about the process of having this physical thing that represented what I had seen with my eyes in that past moment struck me. I mainly drew and painted as a kid, and developed a stronger interest in photography in high school, though I had no way to study it there. I was highly discouraged by family to pursue photography or anything art-based, for all the typical “you won’t make any money” excuses. My second semester of college, I decided to enroll in a Painting class anyway, which got the ball rolling. I had to petition the dean to get into a Photography class, as it was always filling up with seniors who wanted a “fun” elective their last semester, and I suspected I might want to major in this. I got into Intro Photography in January of 1998 at Tulane University and never looked back.

BD: Who or what do you consider as a major influence in you work?

BC: Well from early on, I would have to say that my fellow grad students and professors were huge, as it was a really bumpy time for me and I wouldn’t have ever become an artist if not for them. Corey George, Christa Kreeger Bowden, Chuck Hemard, and Paul Dunlap all watched me stumble through many an awkward critique and patiently listened to me whine afterwards. My professor and mentor Michael Marshall introduced me to a whole other world of photography I didn’t know existed but was exactly what I was looking for. Ben Reynolds’ support was huge, and I think Rick Johnson is single-handedly responsible for talking me off a metaphorical cliff when I reached the decision to quit grad school altogether.

In more recent times, being the director of a non-profit public darkroom in Asheville for several years, and the everyday conversations I had with people about it, was a huge influence in the work I have been making for the last four years. Previously I had been making a lot of mixed media pieces, using digital-based capture and non-traditional inkjet printing, but the whole time I had been teaching traditional darkroom classes. When my previous work came to a halt, both in terms of my concepts and technique, I turned to the current state of analog photography itself as a major inspiration. I told visitors to my darkroom that it was probably one of the most exciting eras in photo history, as we were watching the darkroom transform from a technology into purely an art form, and we are living through all the interesting growing pains of that process. I found the work of Pierre Cordier, the inventor of the chemigram, and the evolution of the darkroom along with his experimental processes dating back to the 1950s all merged and resonated with me.

BD: Whose work do you admire?

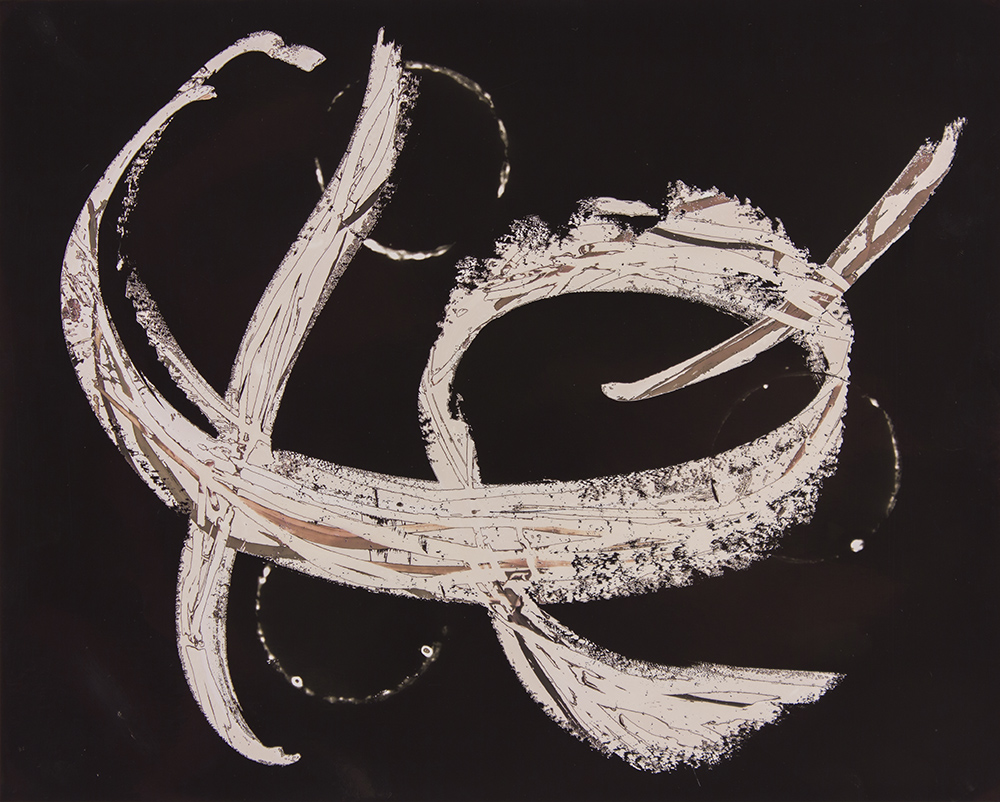

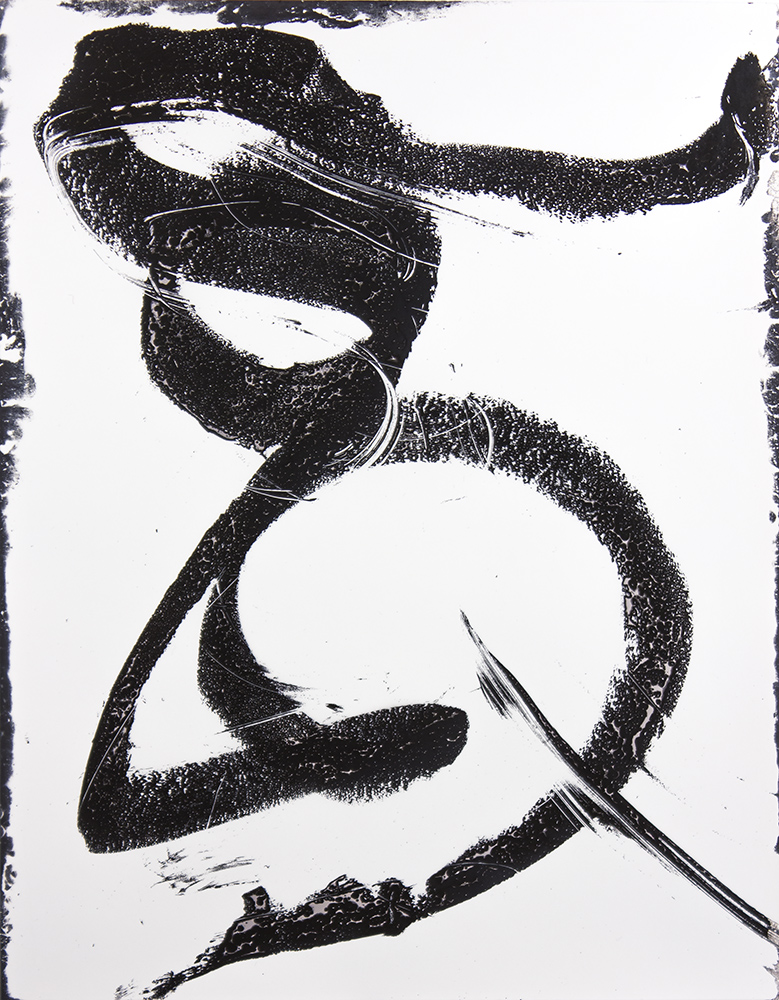

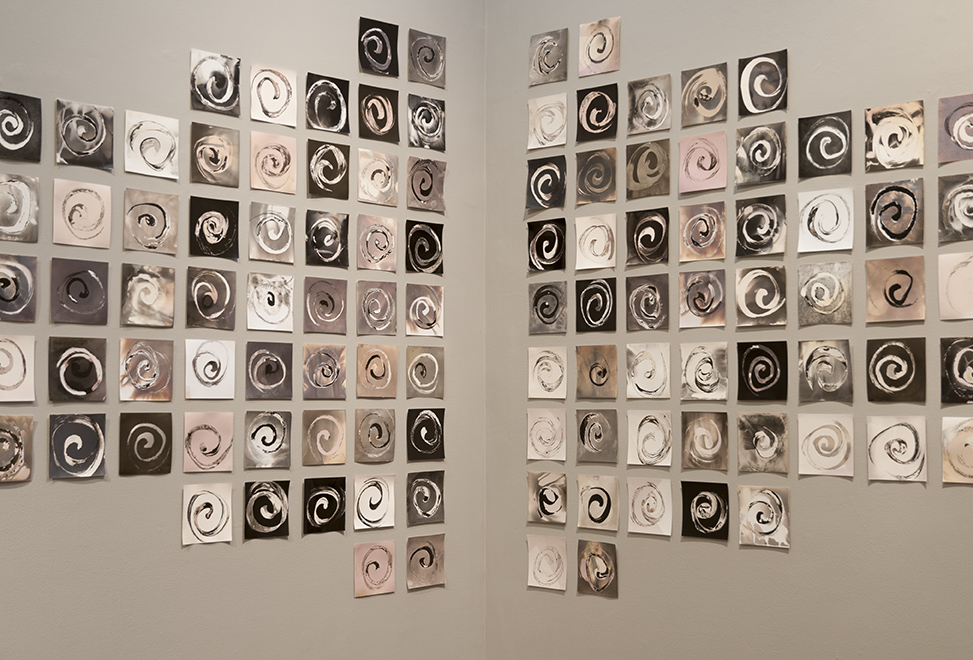

BC: There are so many analog-based artists doing experimental work right now that I get really excited about – I found the work of Alison Rossiter, Mariah Robertson, and Marco Breuer early on in my chemigram work. Chris McCaw, Matthew Brandt, Christopher Colville, Meghann Riepenhoff… I’ve long admired Dan Estabrook’s work for its aesthetics and content, but even his more recent work, as he references photography as sculpture, very much resonates with me. Being that a good part of my work is about the gesture, I often cite Franz Kline and the power of his mark-making, as well as certain elements of Aaron Siskind’s photographs. Jackson Pollock has become more influential to me in recent years, which actually surprises me a bit. It’s not so much for his style, but in his process of needing to be in a certain mental space when making work, almost like a trance, and the importance he placed on ritual and the subconscious.

BD: Can your share your process?

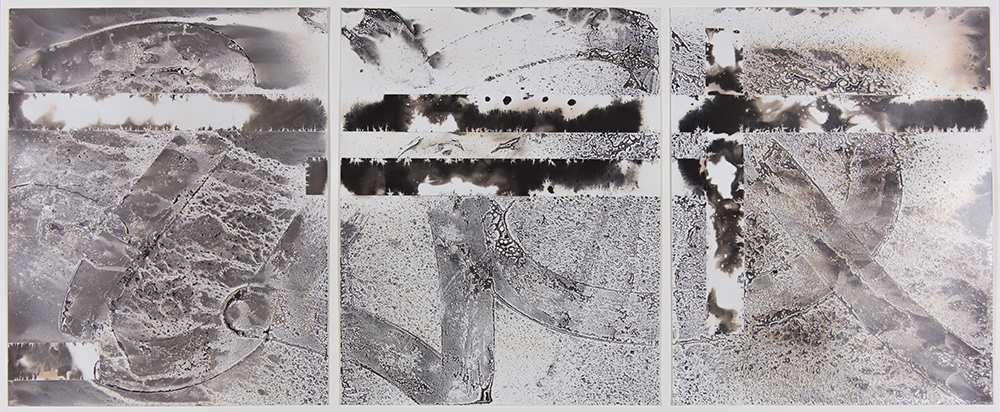

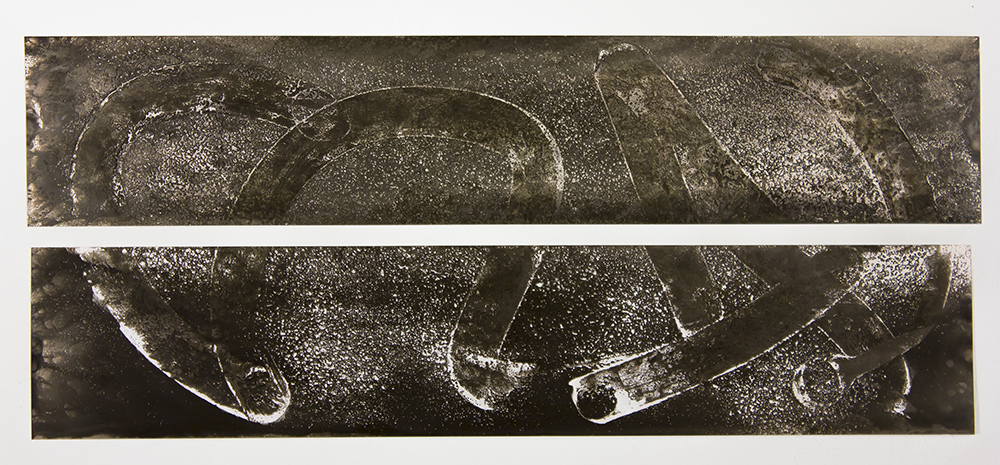

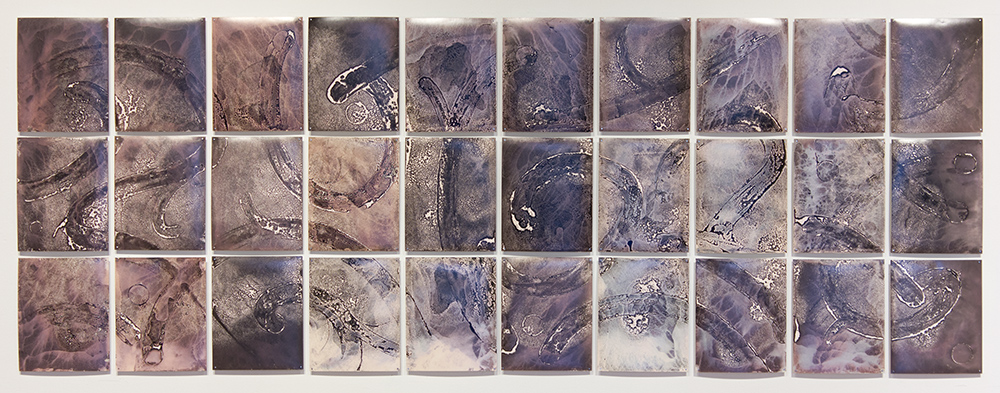

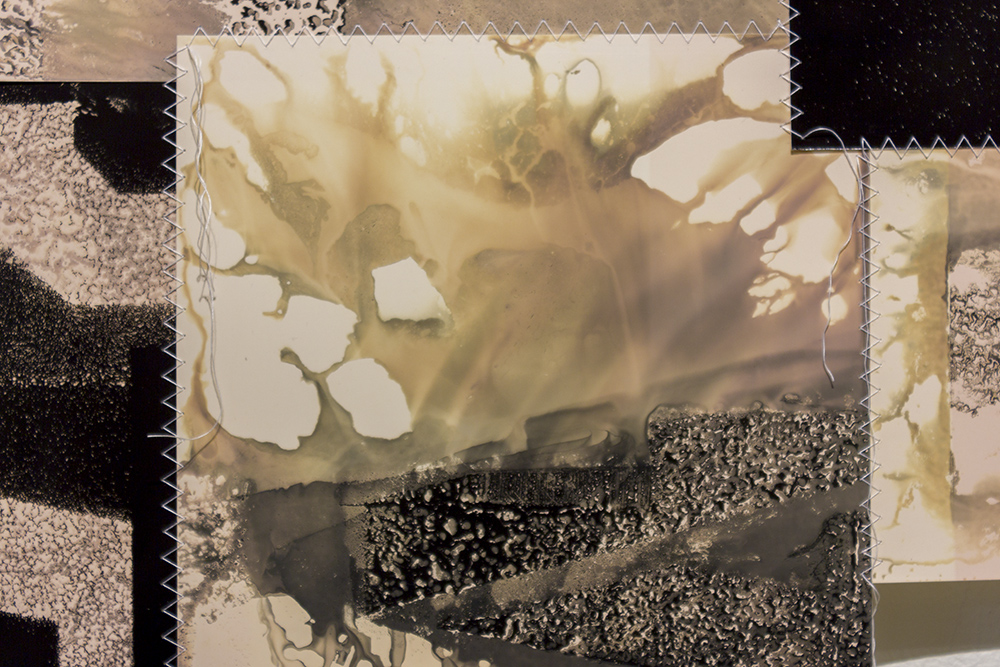

BC: My work is based in creating chemigrams, which are sometimes the end point, but more recently have become a starting point for larger installation pieces. A lot of my work is based in gesture, in mark-making that resembles language. I studied as many languages as I could in college. The idea of making marks to which people ask “what language is that?” has always been deeply satisfying, as though I were creating my own secret language. My frequent goal is to make compositions that work on their own for their mark-making, but a majority of them don’t – the photo gods can be moody. There are several subsets of my work that make use of some of these failed compositions: I break down those pieces into strips and work with formal elements to create a sense of movement or symmetry with collaged panels. My most recent pieces involve taking strips or whole pieces of chemigrams and sewing them together to create new pattern-based compositions. I’ve been excited about introducing my sewing machine into the mix for years, and now the thread is becoming a more prominent element. I’m really interested in the relationship between the two – how at one time, a sewing machine was seen as this automated, technologically-advanced way to make clothes, but time has turned it back into something unique and handmade. The same can be said for photo paper – a commercially-made photograph had long been a silver gelatin print, and now it’s seen as this unique art-based object. I also work with chemigrams on roll paper to get at more of my concerns of looking at photo paper as a sculptural object, emphasizing its physical properties to make 3D installations.

BD: Could you describe the chemigram process?

BC: Chemigrams are made with no negatives, no enlarger, just light, traditional paper chemicals, and the possible use of a resist. They can look like paintings, drawings, or even near-photographs when introducing printmaking into the process. So let’s say I want to draw with a stick of butter on photo paper (one of my favorite resists), and I then take that piece of paper to the developer. Because we are working in the light, everything except my drawing will turn black – the butter protects the paper from the developer. I can then take the print out of the developer, wash off the butter, and introduce the print to the fixer, and my drawing will be preserved in white. By alternating the order of the chemicals, and playing with their dilutions, I can actually introduce color into the prints as well. That’s an important part of the process for me – balancing the mark-making with color, value, and texture to create a composition that can stand on its own.

BD: Why do you do the work that you do?

BC: I think it goes back to my early experiences learning photography. After my first few years of studying photo, I began to shy away from the darkroom and get more into printmaking and papermaking, eventually more mixed media and installation. Silver gelatin prints were still the standard in the photographic world in the early 2000s, but quickly becoming unsatisfying to me. I wished to see the physical mark in my work, and to create objects. Photography as I knew it felt mass-produced and devoid of this materiality. While so many of my fellow students would complain while in the darkroom about wanting to be done with printing so they could get back to shooting, I was the complete opposite – I was happy to spend days exploring the possibilities of one negative. When visiting art museums, I was drawn to paintings more than anything – to see the actual brushstrokes and reflect on how each one was put in place by the artist’s own hand. Yet through all this, I always identified as a photographer.

I spent a lot of years making work that was necessary for me to explore the peculiarities of my upbringing, despite its difficulties, and when that work came to its needed end, the chemigram process quickly pulled me in. The fact that I am drawing on photo paper satisfies that missing mark of the artist I experienced so long ago. Just picking up a paintbrush wouldn’t do it for me – I feel like each piece I make is this collaboration with the mysterious properties of silver gelatin paper. A lot of it is about getting to exist in that place of awe and discovery – I think about how rare that is becoming as we are more and more connected to constant correct answers through our screen-based lives. The variables involved in chemigrams are so vast that from my point of view, there is a lot of rich juicy mystery in each printing session. I think our society is experiencing the negative impacts from a deficit of mystery and resulting wonder – I see this in the struggles of my students. I’ve always felt that one of the major goals of art is to provide wonder, and I’m grateful that my artmaking process provides a healthy dose of this for me.

BD: How do you navigate in the photography world ie: finding galleries, paying for shows, garnering exposure, balancing this with teaching?

BC: I feel like I’m constantly on the lookout for opportunities to get out there in the world – I haven’t really learned to say no yet, which I hear is a bad thing. I’m starting my third year as a full-time professor, and while obviously teaching can get in the way of my own work, in a lot of ways I feel like it’s helped me focus more. That might be more of a result of getting off the hamster wheel of living in Asheville, where at one point I was juggling 5 jobs and still struggling with its cost of living. Now that I’m a bit more settled with my school facilities and classes, I’ve been able to push my work a little more in the last year – although crafting a photo program still feeds into the bigger pot of what excites me about being a photographic artist and educator.

I just feel very lucky that I love what I do, and I don’t really tire of doing research on shows, festivals, teaching opportunities, etc. I don’t have a ton of “hobbies” that aren’t art-related. My partner Ken is a distiller, but he also went to art school, so I get a lot of encouragement and great conversations about art and art opportunities. I try to pat myself on the back more for how much I apply to rather than how much I am actually accepted into. I tell my students this all the time, that you can’t get bogged down and ultimately discouraged by rejection, just put the emphasis on your effort, and at least a portion of that will work out.

The cost of it all is of course a deterrent for a lot of people trying to get their work out there in the world. I think I am just fortunate that, other than good food and drink, I’m a pretty crappy American consumer. Even for years when I struggled more, I always had a bit to spare to send my work off to a show or try for other opportunities. I always felt that I was just passionate enough about what I was doing to be able to prioritize having the means to stay active.

BD: What defines success for you?

BC: The most simple definition for that I can think of is being able to make a comfortable living doing what I love. And by that standard, I guess I have already achieved success. Because I think it’s human nature to always strive for the next big thing though, I have some ideas for next-level goals I’d like to work on. I think when you’re young, it’s easy to adopt the idea of success meaning fame, and that usually means fame for fame’s sake. I think there’s so much exciting stuff happening in photography right now, and how it relates its moment in art history right now, that I’d like to be remembered as being at least a small part of that conversation. Maybe that translates into being published in some books, maybe it means my work was sold by some galleries or collected by some museums and was valued by people who appreciate the evolution of art. It could be embodied by a shift in being sought out more than I have to seek. I’m often thinking about the relativity of success though, as I address this with my students, and I consider how I’ve already achieved things that my 18-year old self would be proud of. I think as long as I can continue to pass my passion along to my students, and challenge myself in healthy ways to make my voice heard at the art table, I won’t cringe at the question of whether I have achieved “success” or not.

BD: What is some interesting work you’ve seen lately?

BC: I was really intrigued by the subtlety of KangHee Kim’s Street Errands – digital constructions that at first glance, could possibly be believable. There’s a similar thing happening with Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs, whose work I saw and really enjoyed at The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip recently. One of my students introduced me to Mark Dorf, and I am specifically really interested in his Transposition series – the way he is taking a digital-based experience and translating it back into a physical realm. I’m also fascinated by how Ally Christmas incorporates videos of her editing photos in Photoshop as subject matter in her Pleasing Memory Picture series. As far as work that is a little closer to my experimental/physical interests, I’m really loving how Robert Calafiore’s work is so engrained into the processes of not just pinhole, but also analog color, and the results are visually stunning. I was asked to jury an experimental photo show at Sulfur Studios in Savannah in March, where I was introduced to the work of Fereshteh Toosi. Her piece Did I Have a Chance? was an incredibly powerful installation concerning an incarcerated essayist in Chicago, executed in chemigram form. I actually find really interesting experimental photography almost daily on Instagram, and through Gallery 1/1 in Seattle, which introduced me to lots of great work from J. Jason Lazarus, Thomas Condon, Briana Tadeo, and many others.

BD: What’s next for you?

BC: The rest of 2018 is going to be pretty full. As of this writing, Ken and I are in the process of buying a house here in Savannah, which would mean I finally get to build my dream darkroom. As I want to push myself into making work on a more regular basis and seeking gallery representation, this would be a huge asset. I’ll be hosting a chemigram workshop at the Society for Photographic Education regional conference at Penland School of Crafts in the fall, as well as presenting a paper at SECAC concerning using analog processes in contemporary artmaking. I’m assisting with starting a public darkroom through Sulfur Studios in Savannah, so I hope that will help build up the photo community here. I’m also in the process of lining up some solo shows in Georgia, North Carolina, and Alabama through next May, so that will definitely push me to keep up with making new work.

BD: And finally describe your perfect day.

BC: Oh man. Can this day be more like a magical realism type of day, where I get to do all the things regardless of time frame or geography? In no particular order, it involves some hiking and blueberry picking along the Blue Ridge Parkway in a quiet spot that no tourists have yet discovered; a really fabulous critique with my photo students in which everyone was talking so much that I could barely get a word in and many breakthroughs about life, love, the process of creation, and our shared experience of humanity were had; a good friend pops into town for a visit and breaks up my typical weekday schedule so that I get to unexpectedly have a day-drink or two while people-watching on an outdoor downtown porch at a perfect 70 degrees; the photo gods grant me a full day of beautiful, unexpected chemigram results and that kind of flowing intense inspiration to keep making work that you want to bottle up and break out for the lean days; my partner and I spend a day cooking a big meal in our kitchen for a bunch of people while sipping on his bourbon and listening to nerdy podcasts – later on we share said tasty meal and have great conversations and laughter with not a cell phone in sight.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Month: Photographers on Photographers, Dennis DeHart in conversation with Laura PlagemanApril 16th, 2024

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024

-

European Week: Sayuri IchidaMarch 8th, 2024

-

European Week: Jaume LlorensMarch 7th, 2024