Lenscratch Student Prize 2023: Top 26 to Watch

Every year, the Lenscratch Student Prize Awards give us an opportunity to celebrate and support the next generation of photographic artists. Hundreds of artists shared their work with us– powerful creative voices that make us truly excited about the future. Before we begin the celebration of our 7 winners tomorrow, we wanted to shine a light on 26 photographers that you should have (and keep) on your radar. Congratulations to all!

An enormous thank you to our jurors: Aline Smithson, Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist; Daniel George, Submissions Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist; Linda Alterwitz, Art + Science Editor of Lenscratch and Artist; Kellye Eisworth, Managing Editor of Lenscratch, Educator and Artist; Alexa Dilworth, Publishing Director, Senior Editor, and Awards Director at the Center for Documentary Studies (CDS) at Duke University; Kris Graves, Director of Kris Graves Projects and Monolith, Photographer and Publisher; Elizabeth Cheng Krist, Former Senior Photo Editor with National Geographic magazine and founding member of the Visual Thinking Collective; Yorgos Efthymiadis, Founder of the Curated Fridge, Photographer; Hamidah Glasgow, Director of the Center for Fine Art Photography; Drew Leventhal, Artist and Publisher, Winner of the 2022 Student Prize; Allie Tsubota, Artist, Winner of the 2021 Student Prize; Raymond Thompson, Jr., Artist and Educator, winner of the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize; Guanyu Xu, Artist and Educator, winner of the 2019 Lenscratch Student Prize; and Shawn Bush, Artist, Publisher and Educator, winner of the 2017 Lenscratch Student Prize.

©Mateo Arciniegas Huertas, Felipe Joshua y El Mocho, 2022

Pratt Institute | BFA Photography

MADISON is a collaborative project where ideas of community, memory, migrant impermanence, passion, and celebration of Latino-American culture are approached; this happens in a shared space that comes to life as it gradually builds and fluctuates week by week. The reenactment that occurs in this communal space is temporary, limited by time and space. It is animated by its participants with the sole purpose of sharing a familiar activity that can bring them closer to home, to what was left behind, to what is dear to them, and by doing so, enabling the construction of new experiences and friendships that sets the basis for a flourishing community. The connecting tissue is Fútbol, bringing more than 20 people together weekly to exercise an act of freedom and of being present, regardless of troublesome thoughts and adversities that exist in their lives outside this place. These weekly occurrences are moments suspended in time, where all that matters is sharing a drink, laughs, a game and pastime, as well as the latest news from home and the Fútbol world.

Madison stems from my experience as a Latino American immigrant living in Bushwick, Brooklyn, my Colombian upbringing, my obsession with Fútbol, and as an active participant in this community. Madison is not the name of a long-gone president nor the name of a fancy avenue in a city. It is a group of friends, the intersection where friendships and belonging are built—an exercise of bonding and learning to live in the present. Cold Modelo and Corona are the drinks of preference. Vallenato, Corridos, Reggeaton, Salsa, Cumbia, and Bachata are listened to, and the games of the major Fútbol leagues are watched on cell phone screens. Representing the permanence of what is impermanent is where Latino American culture, Spanish language, and Futbol live. Madison es un paréntesis Latinoamericano en el Norte.

Thanks to everyone at Madison for welcoming me years ago into their community and the Madison family. Gracias a Pachi, Suegro, Tio, Boli, El Pan, Bailemos, El Chori, Ramon, Felipe, Pillo, Prins, El Chino y sus primos, El Mocho, Rafa, Chui, Frank, El E, David, Peru, Experiencia, Masche, El Tilin, Jeffry, El Don, Joshua, Oliver, el Tanque, Diego, Junior, La Doña, Luis, Oscar.

Follow Mateo on Instagram: @mateoah

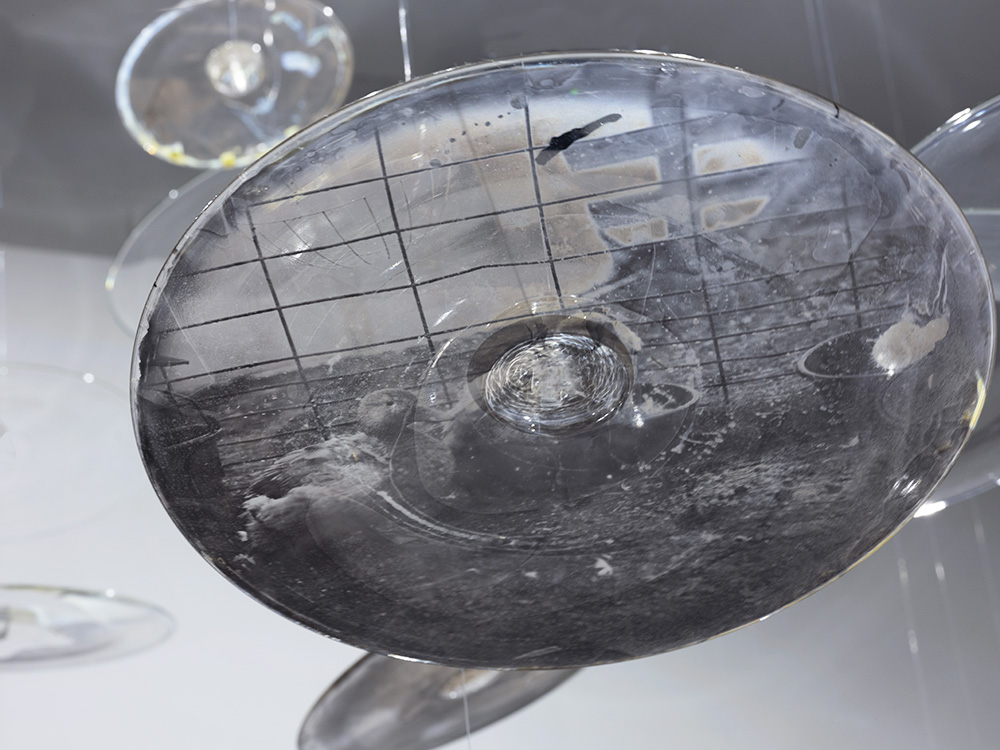

©Lynn Bierbaum, All Memories Fade, Installation of Wet Plate Collodion on Blown Glass, 2023

Rochester Institute of Technology | MFA Photography and Related Media

All Memories Fade is an installation and sculptural exhibition examining familial connection through my developed fear of forgetting. These works comprise many materials, including glass, resin, silk fabric, wet plate collodion images, and chemigrams. This installation uses light and optical variants to communicate the fear of losing one’s most cherished memories in life. All Memories Fade draws inspiration from my family farm in Minnesota that had been sold when I was young. The encapsulated sculptures and installation produce a distorted perception of home through material memory, utilizing light and shadow to highlight those distortions and abstractions that checker one’s past. Many elements within the installation All Memories Fade connect process and sensory engagement with audio and movement to communicate the ever-changing nature of memory.

Follow Lynn on Instagram: @lynn_bierbaum

©Elena Bulet I Llopis, My mom’s eye

Rhode Island School of Design | MFA Photography

My grandma Mari, my mother’s mom, migrated from the south of Spain due to shortage and economic difficulties and built up a family in Catalonia. She died when I was three, and since then I have tried to find her in a yellow-flowered blanket that was at her house. Grandma Elvira, from my father’s side, is still with us, and she used to spend part of the summers in a house in the countryside with a pond. At first, the pond was used to water the surrounding agricultural fields. Decades later, it became the place where several generations of my family would swim together.

I began this project by looking at both of my grandmothers’ archives as visual articulators of place, belonging, and personhood. They showed the morality of a generation, in terms of what deserved to be included and what remained silent. But also were the basis for understanding the tensions that permeated their lives. People who grew up in times of postwar and dictatorship in Spain and who have been marked by heteropatriarchal violence from their partners.

To make the pictures, I investigate what it means to return to childhood as an adult. I perform activities my relatives used to do when they were young, like playing string games with their hands or collecting shells on the beach. I embrace the idea of play as a space where one can be imaginative and vulnerable, but also a space where one can be hurt.

There is a lot of pain that comes from the demands of heteronormative institutions, wounds that are unconsciously inherited and reproduced generation after generation. What tensions lie beneath the structures of masculine control and power within my family? How do we read between the cracks of this trauma: of my mother and her mother before her? Of my father’s mother? How do we confront–and begin to weave–the unsaid, the suppressed, the broken, into emergent possibilities of being when so much of it preceded your own existence?

I began this project with a partial aim to come to terms with the roots of my story. I have found that I do not need to render things visible, nor do I want to. The blanks of the archives have opened a universe of possibilities to rethink my grandmas’ lives in terms of agency and identity and–in some ways– have liberated the work from the weight of uniquely playing witness, despite my continued desire to acknowledge my grandmas’s paths.

Follow Elena on Instagram: @elenabulet

©Cenìnye, Her Beauty, 2023

School of the Art Institute of Chicago | BFA

I had spent more time in America than in my own home. 4,091 days to be exact. I still remember the day I left Liberia. My mother was crying as if she had lost her son. I stood right in front of her, alive, suitcase in hand, still waiting for my flight. She was sad, anxious, and hopeful. I was just excited, a nine-year-old boy who had not traveled before.

A quick Google search for the poorest countries in the world will introduce you to my lovely birthplace, Liberia. When I moved, I left not only my mother and brother, but cousins, uncles, aunts, and countless more family members I can’t seem to remember. I left my grandmother there too. She got sick, however. She went to the hospital and the doctors refused to see her because she couldn’t pay their bill. I imagined she knew she was going to die that day.

My grandmother’s last day is not uncommon one in Liberia. Many people share her story. After its first civil war, Liberia fell to poverty and has not recovered since. The country trudges under a cloud of impoverishment. I remember when I first arrived in the America I was so malnourished the doctors told me if I had spent another year in Liberia, I would have died.

Many people are aware of the civil wars that led to Liberia’s poverty — popular media has spread numerous images in of Liberian rebels ruthlessly killing each other. Many people, however, are not award of the history that caused these civil wars. Liberia was founded in 1822 by America as an outpost for returning free slaves. Most, if not, all the slaves they sent, did not originate from Liberia. For them, Liberia was a foreign land. They viewed themselves as Americans, took control of Liberia and enslaved the natives Liberians already living there. This imploding tension is where the civil war stems from.

Media and research fail to study and acknowledge this history. Instead, they focus on the cruelties of the civil wars and craft a persona for Liberians that is violent, filthy, and lazy. They disregard the families who survived and are admirable trying to plant a seed for their children in the debris of war.

Son of Liberia aims to center these families, proclaiming a new narrative and deposition for Liberia while countering the stigmas that surrounds “developing” countries. As media and research emphasize their poverty, effectively asserting Liberians as people with nothing of value, Son of Liberia counters with the opposite.

Son of Liberia explores themes of possession and poses ones’ humanity as thing more valuable than any coin. It aims not to rewrite the history of ownership or subjugation that has tore the country down, but instead offers a way forward. Son of Liberia asserts the people of Liberia as evidence of the country’s wealth, potential and beauty.

When I left Liberia eleven years ago, I left with memories of an orange sun at seven in the morning. I left with memories of a soft orange gleam in a familiar town and of a boy running on golden sand. I left with memories of an orange oasis. Perhaps nostalgia, the longing for home, lit these memories orange — even as a kid, I was certainly aware of the poverty in Liberia and of the numerous people that died daily. Yet, whenever I thought about Liberia, I remembered only the sun, the familiar town, and the boy running on golden sand.

Follow Cenìnye on Instagram: @clutch.andrew

©Paola Chapdelaine, (Right) Portrait of Radar, who’s VRChat avatar is a small mouse, and which was made based on a real-life outfit including a made’s dress and two furry ears. (Left) Radar’s compass. As an analog person, she doesn’t use a smart phone and thus relies on a compass to get around. She also uses an old CRT-monitor instead of VR headset, which makes her a VR desktop user.

“I maybe have more of a connection to my avatar than I do to my physical self. That was the epitome of the person I wanted to become. (…) My VR self influences my real self and vice-versa. I’m fully integrated at this point.” – Silent

Silent and Radar, two transgender friends who spend most of their time on the virtual reality platform VR Chat, have found there a true sense of belonging. For many, this growing community of about 30.000 people has acted as a space to explore identity and overcome boundaries: walls, borders, language… And in this, to create an environment of limitless, fast-paced creative expression.

Living in New York, Radar experiences VR as “a simulation of a world that doesn’t have landlords.” The rent-stabilized apartment complex in which she lives with her parents and sibling is the only she has ever known. “I just turned 30, and I live in the same apartment that I’ve lived in my entire life. And I will never leave. Or rather, I want to leave, but I cannot afford to live anywhere in the city. When I walk around the Lower East Side, there’s a bunch of closed-down storefronts. I remember what used to be there. I walk and there’s five weed stores that all have the same fake linoleum wood floor, and the same shitty neon signs.” For them, it is never about the technology itself, but always about the human emotional need and how it is being satisfied.

As such, this story goes beyond tech or the notion of ‘digital future’. Rather, it speaks to the ideas of community and space — those lacking in one’s immediate, real, surroundings. VRChat is the punk underground scene of virtual reality, largely unknown by an audience numbed by the techno-futurist idea of the Metaverse.

By combining several photographic forms (portraits, still and daily life, virtual reality vignettes, and large format photographs), this project confronts and blends the idea of the real and the non-real, the virtual and the tangible, the digital and the analog.

When both worlds start to merge, how is the ‘self’ defined? And what does it tell us about our real, tangible, world?

Follow Paola on Instagram: @paola.chapdelaine

©Yukai Chen, Revisiting (The Living Room), 2023

Massachusetts College of Art and Design

Growing up in a rural area of Xiamen, China, I would attend the local temple with my parents. There, we served the gods and watched the captivating opera performances. I distinctly recall one performer in particular, a woman with pink makeup and dressed in male attire, who sang boldly on stage.

During a period when I struggled to accept my changing body, my hair growing rapidly and my throat expanding, I found solace in the memory of that gender-bending performer. She danced and sang in a traditional story on stage but she was fearless and powerful. I am also inspired by my childhood memories of playing various masculine characters for a memorial album in a photo studio. On the contrary, I made self-portraits again in my studio but took full charge of my body and my desires this time on different stages, and regarded it as a resistance.

I also sought refuge on the internet, regarding it as a safe haven, a temple for a queer individuals where I could temporarily forget about the present and immerse myself in various cultures and explore my desires without fear of judgment. Consuming every bit I liked online, I expanded my desires into the debris of consumer culture in which I attach my hope of alternative reality. My art serves as a bridge between my memories, my desires, and my future. By acknowledging my queer identity and the potential of my body, I create new ways of seeing and being in the world. The Factory of Desire is a manifestation of my personal journey towards self-discovery and a celebration of the power of picture-making to advocate for alternative social realities.

Follow Yukai on Instagram: @cykkai

©Rosie Clements, Dad on Horseback, 2023

University of Texas at Austin | MFA Studio Art

In What Part of Me is You, I’m thinking about the ways that the relationships we have with other people influence us physically and psychically.

Using a UV printer and a mesh fabric, I print through the mesh onto paper, and then remove the mesh. Some ink passes through the holes, and some is retained on the fabric itself, resulting in both a ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ of the image. The series incorporates archival photos scanned from slide film taken during my parents’ honeymoon alongside my own photographs, which depict other relationships of people close to me. Interspersed are images of my current partner, always obscured.

Throughout this process, I’m thinking about where ‘I’ end and ‘you’ begin. The mesh acts as a barrier that represents how we never truly know someone else—how we can never be someone else. I’m interested in how our brains can still ‘read’ these images despite having removed most of the information. We fill in the gaps. This makes me think about the fallibility of memory and how it can be fabricated, embellished, and altered.

“Instead of trying to define the other (‘what is he?’), I turn to myself: what do I want, wanting to know you?” – Excerpt from ‘A Lover’s Discourse’, Roland Barthes

Follow Rosie on Instagram: @_rosieclements

©Nykelle DeVivo, Birth of the Purple Moon, 2023

University of California San Diego | MFA Visual Art

My practice is a personal meditation on the liminal space between our world and that of spirit. Less interested in the destination, my photographs work to document the shift. The moments between moments of time, the pause between the clap.

Raised in a deeply religious household and honoring the language of afro spiritualism, my images reflect a lifetime of reverence for the divine while simultaneously bearing the cross of anti-Blackness that saturates our relationship to the land. In that, they work as a form of escapism in the hopes of a new world to come.

In my images, Black is potentiality. In the shine, there is god, and in fire, there is change. The concurrent states of Black existence (the past, the present, and our futures) can collapse in a singular moment, and image-making has the power to bear witness. The camera can act as a space for the refusal of a history of violence in that it may be used as a tool for communion.

Now I find spirit in the collective hopes we place on a pair of sneakers, the way flowers reach for the sun, and the eyes of those I love. All can act as a portal to other worlds and an entrance for spirit unto ours.

Follow Nykelle on Instagram: @nykelle_devivo

©Chloe Dichter, Manischewitz Portraits, 2021- 2023

University of New Mexico | MFA

The choice to use archived family imagery translated through the cyanotype process acts as a bridge between spirituality, history, and memory. Reconstructing my family tree through cyanotypes on matzo crackers draws reference to consumption and fragility. Each crack and fracture act as visual indicators of lost cultural roots and erasure. My efforts are frantic to conserve both the integrity of the crackers and circumvent the ephemeral past. By making these images of my family on a material as perishable as a matzo cracker, I’m forced to confront their impermanence. As fleeting as the memories captured in the original photographs themselves, the crackers decay and their existence is completely temporary.

With this work I am contemplating my precarious ownership of my history as an American Jew and examining the emotional weight of being the last person in my family to carry its original name.

Follow Chloe on Instagram: @cyanodyke

©Hazel Dunning, Laundry Day, 2022

Bard College | BA Photography

As a child I spent hours at a time lost in various worlds, both tangible and imaginary. I would paddle our canoe across the pond and enter fairyland, or build an addition to the cardboard village of barbie mansions which lived in the guest room. Other days, I was an actor rather than an architect, filling the role of doctor, or mother, or teacher. I easily accepted, and willfully ignored, the discrepancies between the worlds I constructed and reality; the fictions were real enough to believe in. Baking plastic muffins in a fake oven, while wearing high heels I couldn’t walk in and poorly applied lipstick smeared across my face. My imagination blurred the messiness of these imitations, painting the fabricated with a false glow of authenticity.

As I aged though, those imitations became more transparent, and their believability waned. I found myself repeating these motions which had once brought me so much joy, and yet I was too aware of their absurdity to engage with them as I had before. I began to feel as if some invisible line had been crossed, as though I had lost both a way of seeing the world, and a way of experiencing it. Unable to backpedal or stop my forward motion, I mourned my lost access to those worlds.

Photography has restored some of that access. I’ve realized that the act of making my photographs is the closest I’ve since gotten to building those worlds as a child. Blending the real and the imagined, these staged scenes allow me to manipulate my reality once again. The camera, blind to both context and time, allows for further control; it is told what to see but it is also told how to see. Training the lens upon these carefully crafted scenes, I coax the camera into seeing how I once saw. The camera can act as a bridge, and as an instrument of reconciliation. In my mind it is a ramshackle bridge, with missing planks of wood and broken railings; it can hold my weight but it is not yet crossable.

From behind the ground glass of the view camera the world is once again painted with a false glow that blurs context. However, as I step in front of the camera, as I enter the scenes of my own making, the context returns, and the camera documents the negotiation between competing emotions. There are a plethora of distractions, responsibilities and life events that, in competing for my attention, divert my focus from moments of wonder. The camera simplifies the world. The view camera allows me to zoom in, and concentrate on the

minute, easily overlooked moments.

While I am overjoyed that the camera allows me access to these worlds I inhabited as a kid, I find myself to be a distant viewer. The worlds that were once boundless are now constricted by the tenets of adulthood. The borders of these worlds have become sharper, and harder to ignore. I can no longer exist fully inside of them, without recognizing those edges which place them inside of this world. This group of photographs chronicles my attempts to reclaim those lost appetites for worlds other than this one.

Follow Hazel on Instagram: @haze.rd

©Brayan Enriquez, 20 Years of Service, 2022

Georgia State University | BFA Photography

And Taste the Dirt Below is an ongoing project about my family and their experience of living in the South as undocumented immigrants. The title was inspired by both my mother and father: my mother, when she recalled how in Arizona, she trudged through mud that went up to her knees, and my father, when he spoke of how he lay planted on the ground, hiding from an officer who was only steps away.

Follow Brayan on Instagram: @_brayanenriquez

©Paul Fauller, Self Portrait as Olympia, 2023

The School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University | BFA Studio Art

Queer domesticity is the next frontier in queer liberation- especially with the relationship between queer bodies, gendered spaces, and domestic comfort. How does domesticity relate to those who have to construct their family, creating a chosen family? My work challenges and creates new ideas of queer domesticity- asking: How can we navigate these spaces in meaningful ways that deconstruct the very conception that is gendered space?

My images are not intended to be characters nor are they purely representational; more so they exist in the middle of the two as vignettes where my body becomes the object of perception- one that is holding space previously removed from me by sex, age, and identity. By juxtaposing myself with domestic spaces, chosen families, and blood families, I emphasize the dichotomy between public/private spaces and personal identity; trying to navigate identity in a world where invisible walls are constructed around queer bodies to restrict their movement, hoping we never move.

Follow Paul on Instagram: @paulfauller

©Conner Gordon, Untitled, 2022

The University of Oregon | MFA Art

It is in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon that the tragic figure Cassandra utters the words, “I speak always truths, never grasped as true.” Cursed by the god Apollo to see the future but to never be believed, Cassandra was tormented by visions of calamity and the apathy of those she tried to warn. Today, her story is more relevant than ever, as we grapple with apocalyptic futures that threaten to overwhelm our capacity to address them.

Taking inspiration from this condition, After Cassandra reframes the Cassandra myth as a point of departure to examine prophecy, uncertainty, and apocalypse. Using images ranging from birds of prey to construction site debris, the series weaves together fragmented visions that echo the mindset at the heart of Cassandra’s story while suggesting a cataclysm lingering beyond the threshold of perception. In doing so, After Cassandra harnesses photographic ambiguity to explore a myth and a moment when the apocalypse feels both intangible and close at hand.

Follow Conner on Instagram: @conner.gordon

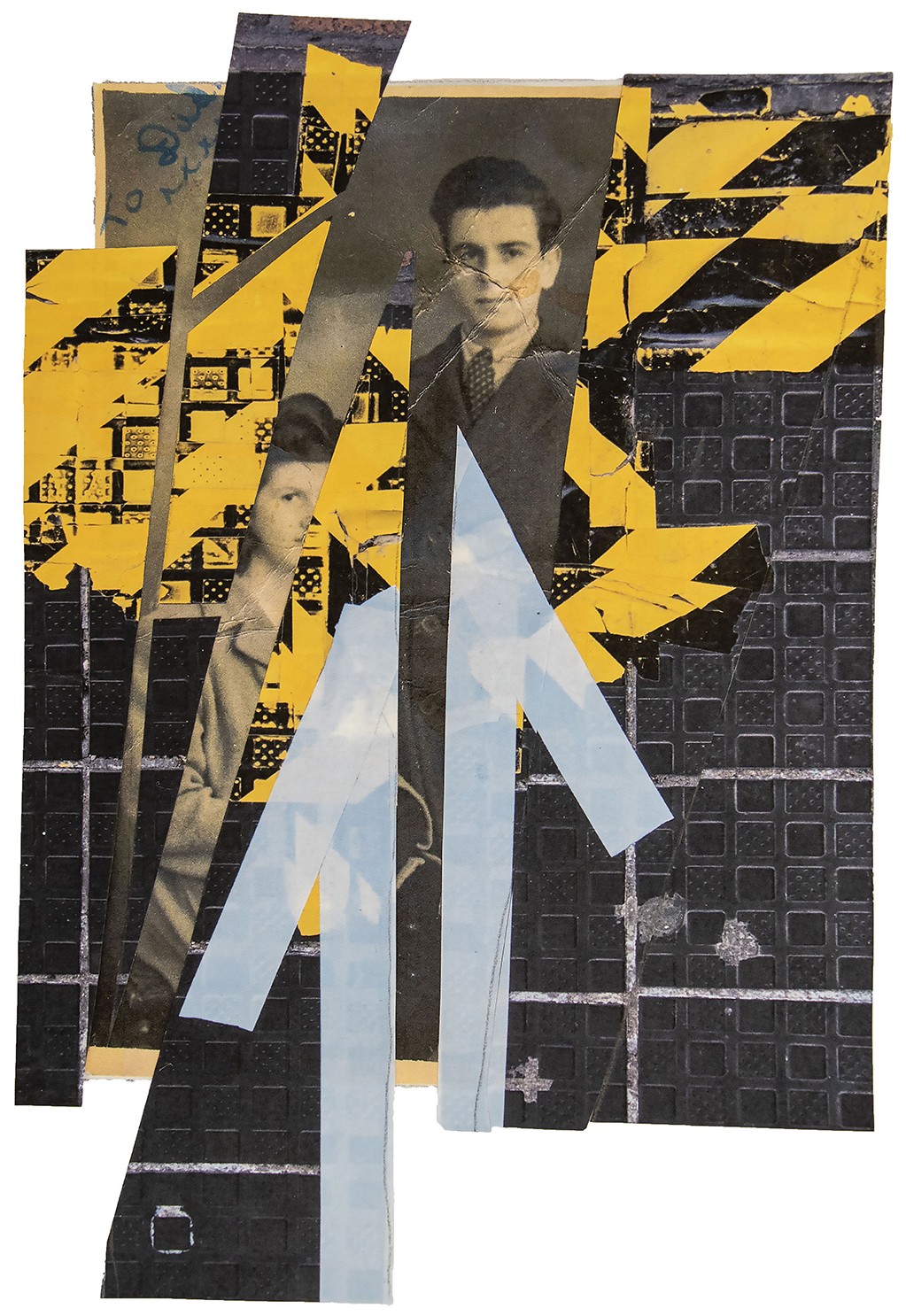

©Sue Greenfield, Fragmented Lives, 2021

Open College of the Arts | BA Photography (Honors)

When the sirens were going is a remembering of the treks people made across Portsmouth city, SE England, during the Second World War, seeking refuge from bombing raids in tunnel shelters cut into the side of Portsdown Hill, a chalk ridge overlooking the city. How did it feel to make those nightly treks? To spend the night in those tunnel shelters?

Eighty years on, I recall these events and experiences through the medium of photomontage and collage using contemporary images and archival materials. I use Covid-19 imagery to introduce hauntological disruption into the work; a sense of the past haunting the present. This came from the realisation that my Covid-19 lockdown walks coincidently followed part of the trekkers’ route; both my walk and those treks imbued with a sense of threat and a need for refuge.

I have no personal or family connection to these wartime events. But as a member of Marianne Hirsch’s “generation after”, whose postmemories are their own memories of other people’s experiences, I remember those times. These images, my postmemories, evoke the fragmentation of daily life, separation from family and loved ones, the presence of danger, sometimes unseen, but which also echoed within our lives during the pandemic.

Follow Sue on Instagram: @photosueg

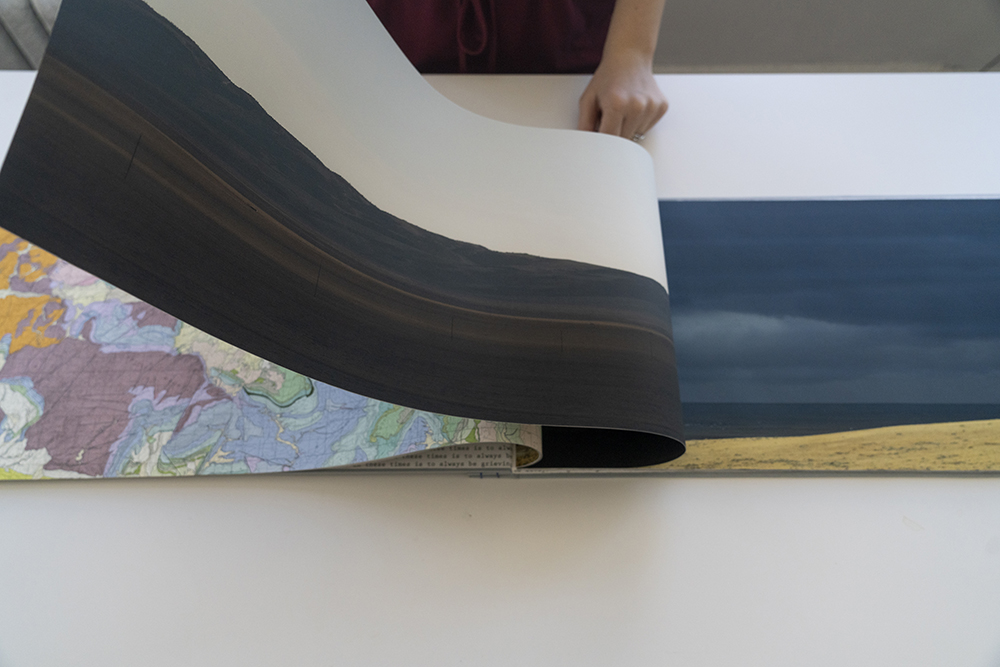

©Jessica Hays, Horizon Line, Artist Book, 2023

Columbia College Chicago | MFA

I, like many others, am deeply connected to the places I live in and find myself longing for more time spent in recognition of the sense of solace, joy, and belonging that can still be derived from the landscapes I am most familiar with. The impacts of the Anthropocene have already infiltrated much of the land I am connected to, shifting them in both clear and subtle ways. In addition to making images expressing the grief and loss of landscape, part of my artistic practice involves making images that are meditations on self in relationship to place, about the ways I experience the land and belong to the landscapes I inhabit. Collectively, I am always working at reconciling the land as both a place of joy and of grief.

Horizon Line is a monumentally scaled handmade artist book rooted in experiences of reverence and appreciation for the land, alongside consideration of the ways in which land may seem empty and limitless but is a the same time divided and subdivided by use and ownership lines. Utilizing photographs, satellite images, and altered maps, the book creates moments to pause and consider the impacts human development has on the land while remaining firmly rooted in a spirit of appreciation for and connection to our surroundings. Scaled to mimic the size of a human body, the book requires interaction and movement from the viewer, creating an embodied relationship with the images and thus the landscapes they represent.

People who feel a connection to any part of the earth or nature are well equipped to strongly empathize with the idea that the planet as a whole is their home, and can find endemic destruction in any area disturbing. As more parts of the earth become damaged and polluted, experiences of positive emotions in relationship to the earth become more difficult. And so we are left with more and more climate grief. Even as we seek out solace in nature, it is less able to provide such relief. If grief is the price we pay for love, then to love the land in these times is to always be grieving.

Follow Jessica on Instagram: @jess_the_photographer

©Kien Hoang, Urban Garden

Hanoi Academy of Theatre and Cinema

This project started during my last days in the hometown – Long Bien, before moving to the other side of the country with my family. At first, going out to take pictures was just an excuse for me to temporarily forget the sadness of displacement. Unexpectedly, that was my very first opportunity to truly witness the changes of the landscape and the people, which I never noticed during the past years.

When I first moved here, Long Bien imprinted on my mind as a sparsely populated suburb, completely different from the city central part just a bridge away. Inevitably, as an energetic young adult, I spent most of the time in the central part, its liveliness caught all my attention. But in the moment, on the threshold of change, I suddenly felt … strangely helpless. My house, where used to be full of people talking, music playing, now just me and the silence remains. Even when I try to recall the surrounding landscapes as a salvation, to the most familiar scenes that I have memorized, it is not the same anymore. The small school on my way back has been abandoned ever since. The old small shrine is now crumbling to make way for construction sites. The green spaces of trees are surrounded by concrete walls from high-rise buildings. LED lights lit up the night made this place look like an unreal land. Changes came with such an incredible speed that I no longer recognized my hometown. Since, every night I play the role of a wanderer, walking around Long Bien, rediscovering the place through the eyes of a stranger. Coming back home in the morning, I take pictures of the objects inside my house as a visual diary of nostalgia filled with exclamations: If only! If only I had spent more time with my family back in the day. If only I had more memories with this place so that when I am away, I have a place to feel like I belong.

Every single day, a vague sense of belonging to nowhere invades my thoughts, making me feel like free-falling into an endless void. This project, somehow, is my desperate race to preserve pieces of my memories of Long Bien, before everything fades away.

Follow Kien on Instagram: @kienhoanng

©Healim Hwoang, Exploring a cultural identity and experience of being in-between

The University of Cincinnati | BFA Fine Arts

The first time I became aware of my nationality was when I was in the fourth grade and transferred to a Korean school in Tokyo. I could not even write my name in Korean, and my parents told me, “We transferred you to this school because we want you to learn our native language.” I have experienced a sense of in-betweenness and struggled to reconcile my multiple identities and find my belonging. This feeling has become even stronger since I immigrated to the United States.

Mother Tongue is a photo series about my experience of being Korean in Japan and an immigrant in the U.S. My work addresses the confusion and frustration about my cultural and national identities and experience of being in-between places. I work with the medium of photography to capture those emotions and experiences of living with multi-cultures in a sometimes direct and sometimes nuanced way.

Follow Healim on Instagram: @lim_hwoang

©Kylee Isom, looking at me looking at you, 2023

The University of Missouri | BFA Fine Arts

MAKE ME FEEL GOOD is a series of self-portraits, still lifes, and photographic objects which centralize around the intersection of feminism and the gaze within a digital cosmos, through the lens of the modern pornography webscape — OnlyFans. This work examines the heightened ways in which the pornographic industry has contemporaneously mutated the gaze to perpetuate systems of gender inequality through the guise of capital empowerment. With a range of methods, this series infiltrates the consumer gaze through the use of imagery and research mined from the OnlyFans site. The work utilizes analog collage to sew appropriated images into environments and hyperbolic costuming, referencing the performative and plastic nature of the OnlyFans ethos. Swatches of spray-tanned flesh, objects from Amazon wishlists of OnlyFans content creators, and pieces of bedrooms are reconstituted as the material residue of the online. This body of work uses crude, physical construction to articulate infinite, intangible digital space. The cardboard stage set is tethered by visible fishing line and artifacts of the bubblegum-colored home studio are erected as paper monuments, standing only long enough for the performance. Censoring, obscuring, or exaggerating weaponizes the power of looking and blurs the boundary between the viewer and the viewed. MAKE ME FEEL GOOD calls into question the platform’s ability to incubate empty connections and false gestures of intimacy centralized around sex, fetish, and performance. The work utilizes pieces of text extracted from the content creator’s automated, subscription-based direct messages, sent as beacons of empty affection. Using the messaging inbox between creator and consumer, this project shifts perceived privacy and intimacy outward to the walls of its environment, smearing lines of sexual foreplay onto flesh-bound tissues. When stripped of their context, the messages are decoded. A neon sign demands — MAKE ME FEEL GOOD.

Follow Kylee on Instagram: @kyleeisom

©Alexander Komenda

Aalto University | MA Photography

I first travelled to Kyrgyzstan in 2016 to visit my father who continued his work in international development and human rights. Our conversations over the years helped shape my interest in the specific geopolitics and culture of the area. It eventually became my place of work also, where I started to unveil questions of home. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kyrgyz areas of the Fergana Valley have been subject to interethnic clashes in recent decades, between Kyrgyz, Tajiks and Uzbeks. Uzbek and Tajik minorities are subject to systemic discrimination. These events, tainted by a post-imperialist landscape, have blurred the line between division and unity in relation to everyday life; they are seldom visible. Following seven trips to Kyrgyzstan between 2017 and 2022, alongside both extensive field research, discussions and readings, this visual amalgamation refrains from any factual purity. They exist as segments entangled in one common history governed by the legacy of an empty promise and corruption. This is over half a decade’s worth of bearing witness to people putting on shoes like watching a glacier move. As much an observation as it is a meditation. The camera is an opportunity to reach out via kinship and reciprocity. Where is the line between division and unity? Such questions become starting points, where the quotidian can be unpicked and contemplated; to capture a feeling, to convey the bond that occurs off camera. How does one encompass it all and depict such complexity and nuance with tranquility, dignity and respect, without exaggerating the tragedy nor undermining it?

Follow Alexander on Instagram: @alexanderkomenda

©Christian K. Lee, from Armed Doesn’t Mean Dangerous, Aaron Banks, 38, and his son Aaron Banks Jr., 08, embrace at a local park on Saturday, May 22, 2021 in Cedar Park, Tx. “The image of the average gun enthusiast needs an update,” Mr Banks said. He is the President of Keep Firing LLC where he has made his son the CEO. Currently he is one of 24 Pistol Instructors certified by the National African American Gun Association.

School of the Art Institute of Chicago | MFA Photography

Armed Doesn’t Means Dangerous began when I realized, that I had only seen negative images of African American gun owners. I became curious as to why that imbalance exists. My goal is not to promote gun ownership, but to utilize it as a gateway to discuss larger issues in American society.

“There is a higher crime rate when people cannot work and earn,” says Chicago resident Angela Ross Williams. The 67-year-old became a gun owner out of necessity to protect herself from crime. Community members such as Angela inspire me to continue this work.

I want to show that gun ownership in urban communities are symptoms of bad policies and lack of resourcing, rather than an obsession with guns. The research conducted by The Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence supports this claim, identifying the root causes of gun violence to be poverty and lack of opportunity, among other factors.

Follow Christian on Instagram: chrisklee_jpeg

©Eli Murdock Lynch, Chew, 2023

Massachusetts College of Art and Design | BFA Photography

“…But still, no matter how much time passes, no matter what takes place in the interim there are some things we can never assign to oblivion, memories we can never rub away. They remain with us forever, like a touchstone. And for me, what happened in the woods that day was one of these.” – Haruki Murakami, Kafka on the Shore

The Blooding Rite is a project surrounding the fragility of existence. How we as people cope with anguish and loss. How we feel entirely powerful and utterly powerless simultaneously through violence or victimhood. Interweaving the unsettling with the curious I create unpredictability throughout, using encounters of everyday life and conjuring moments to photograph.

I had become exposed to the idea of death when I experienced my first family hunting trip at the age of six years old. I was taken out with the two guides, my brother and father, and the pack of hunting dogs. The snarling dogs surrounded a boar in the swamp, their barking piercing the humid air. When the boar seemed to have understood its imminent death, I put a bullet in its forehead. Not even old enough to walk through the mud on my own, I closed my eyes obediently as John the guide instructed. Staunch fingers ran over my face, warm blood and brain matter began crawling down my cheeks, a ritual to the success of my first hunt. Not long after this trip, my teenage brother passed away, and six weeks later, my father met the same fate.

Photography is my tool to bear witness to a lived experience and a grapple with the spirituality surrounding existence. Using inherited beliefs and legends, I meditate on why we as a population indulge ourselves into the sinister. Does it give us comfort to know others have experienced similar emotions? Are we hoping that if we conjure malevolence it will in turn make our experience with death a relief? What stories will be told about me when I am gone?

Follow Eli on Instagram: @elilynchphoto

©Jade Nguyễn, Blessing, 2023

Illinois State University | MFA Fine Arts

Commerce(d) Culture, a study of the consumer culture displayed in various Vietnamese grocery stores across the United States, explores the intersection of consumption and cultural practices in Vietnamese diasporic communities. From Little Saigon in Southern California to Philadelphia and smaller towns in rural Illinois, these stores range from independent corner shops to larger multi-aisle supermarkets, attracting thousands to millions of shoppers of cultural nostalgia or global cuisine exploration. These stores exist not only as a place of transaction but also a celebration of intercultural communities and immigrants’ experience on display.

For many customers, shopping in these stores fulfills a craving for more than just items on the shelves. For members of Vietnamese diasporic communities, the goods and decorations carried in the stores portray a construct of nationhood and nostalgia of motherland. Unlike the ethnic section in other generic supermarkets, immigrant grocery stores are where people can shop for their everyday cooking ingredients and have the privilege of doing a quick grocery run without the constant reminder that they are aliens in the communal spaces they inhabit. By looking beyond the offered products, the photographs unveil the complex intersection of history and culture, placemaking and displacement, and the aftermath of globalization and mass-commercialization muffled under a party of attractive colors, sounds, and textures in the mundane subject of a grocery store.

I grew up in Vietnam behind a grocery store, well-acquainted with towers of cardboard boxes, friendly Saigonese banters, and an excessive amount of goods at the tip of my fingers. When I moved to Upstate New York, the nearest Vietnamese grocery store was an hour and a half plus a ferry ride away in Vermont, or two if I took the scenic route to the Canadian border. The piercing white Adirondacks called for a hot soup that cannot be made from the ingredients found in a neighborhood Walmart, so I took part in a monthly ritual, journeying across Lake Champlain to keep in touch with my cultural identity. For a special treat: familiarity. Once I moved to the Midwest, the stores became the few places where I could dust off my Vietnamese vocabularies as I read brand names on packages and “help wanted” signs on the community boards. The storekeepers recognized that I was a compatriot before I said a single word; all they had to do was look at the assortment of goods in my basket. It brings me great comfort to know that in these spaces, I am understood.

Follow Jade on Instagram: @jd.ngn

©Hannah Nigro, $40 Per Grave, 2022

Rhode Island School of Design | BFA Photography

“And in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the

earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea.” — Timaeus

In Italo Calvino’s “Invisible Cities,” the narrator poetically constructs cities for Ghengis Khan, who has asked him to discover the world. The city of Baucis swims in the clouds and Raissa’s inhabitants live two lives, at once unhappy and happy. At the end, the narrator reveals that he has only ever been describing one city : Venice. What if this city was Atlantis? Plato’s “Critias” tells of Atlantis, an island allotted to Poseidon, sunk by an earthquake after a failed battle with Athens. These folktales materialized for me out of the submerged towns of the Catskills that have been lost to water and time. Both Atlantis and the Catskills bear likeness in their pre-sunken states: rich in fertile soil and abound with flowing water. Just as “Critias” ends abruptly, leaving the history of Atlantis unknown, the continued lives of the sunken Catskill towns go untold. This project proposes to capture, dredge, and reconstruct the lives and structures of the very real, abandoned cities sapped and sacrificed for the good of the New York City metropolis.

In 1905 the New York State Legislature passed the McLellan Act, beginning the city’s long-lived campaign to obtain populated rural lands for use in an ongoing project to supply New York City’s increasing population with adequate water. The project was to be realized through the creation of a complex network of reservoirs and aqueducts which would alter and destroy the natural ecological landscape of the Hudson Valley. Within 10 days of an appraisal commission’s appointment, villages could be condemned and purchased for a fraction of their worth. Infrastructure would then be set ablaze, and submerged in water meant to be funneled south to the island of Manhattan. Valley lore claims that when the reservoirs’ levels drop low enough, remnants of homes peak through the water’s surface.

The conceptual draw of these water-logged hamlets is the irony of their destruction as a simultaneous act of preservation. Today the structures of these submerged towns survive as magical, subaquatic metropolises. The Catskills cradle the fantastical worlds of Ashokan, Neversink, Olive and twenty-three other towns which were glazed in a liquid encasing of time. Underwater ghosts continue familiar patterns of life – navigating bartering economies, preserving familial relationships rooted in land tilling, making yearly trips to the big town of Kingston. The once spiritual connection between the living and the land is marred by the state’s unforgiving history of exploitative use. How have such decisions that support production over sustainable stewardship rerouted lives and informed the current climate crisis?

My project deals with a living archive. While the majority of documentation is located in the early twentieth century when the project was first conceived of and realized, building continues today. Tunnel 3, a 60-mile-long water supply route, was only completed in 2021, acting as a third connection between Manhattan and the Upstate reservoirs. I am at once sifting through images from the fateful 1907 construction of the Catskill Aqueduct, and speculating about a future in which New York City’s water needs go unmet. I am fascinated by the events of forced land dislocation, motivated by capitalist priorities that at their core, further divide the “rural” and the “metropolis.” Destructive rumbles traced to over a century ago, still run through veins of the state’s topography. I’m interested in how this infrastructure decision and turning point served as a catalyst and foundation for land indifference.These images look to inform a narrative of upheaval and exploitation, tease out our complex relationships to the horrific yet enchanting ramifications of an engineered topography, and illustrate the disastrous decoupling of the environment and humankind — a cleavage that continues to affect our present, urgent realities.

Follow Hannah on Instagram: @hannahnigro

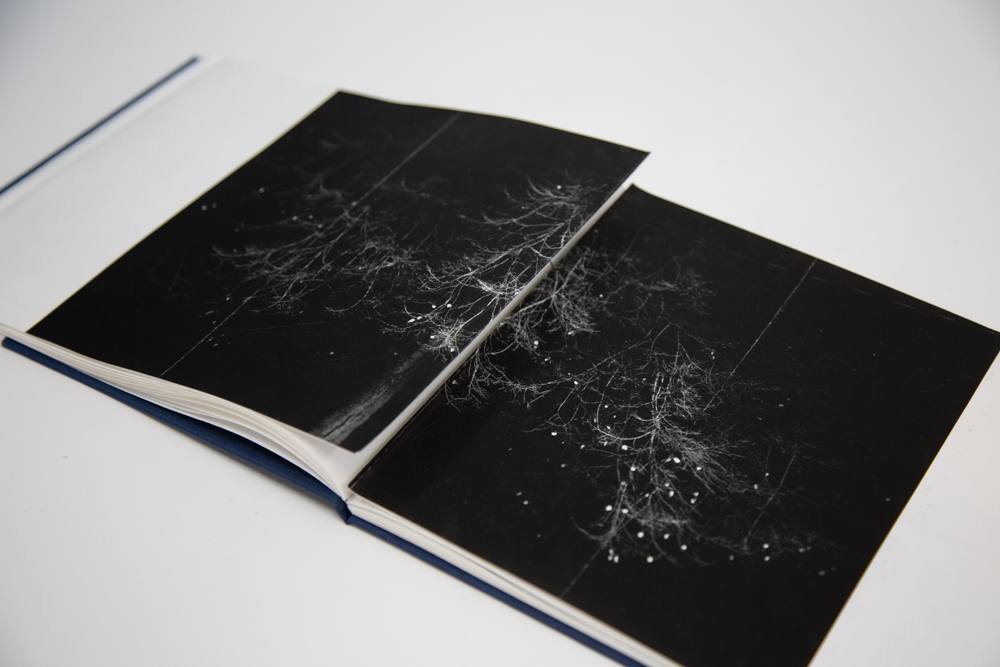

©Angelica Ong, 「霜の声」 “heavenly bodies”, hand-bound, drum leaf-bound photo book, 2023

School of the Art Institute of Chicago | BFA

From frozen ponds to birds, 「霜の声」 “heavenly bodies” captures the starkness, ephemerality, and subtlety of the beautiful entities of winter. This book carries two titles, one in Japanese and one in English, which do not translate to each other. 「霜の声」, read as “shimo no koe,” directly translates to “voice of frost,” referring to the silence of a deep, cold winter night. Over the course of winter, I took numerous slow walks in the snow to discover its quietest yet most penetrating moments. While sequencing and choosing the images for this book, I made prints of all the potential selections so I could physically manipulate them, cutting them up and cropping them in unconventional ways. I then rephotographed these prints.

By rephotographing them, I retained every scuff mark and blemish accumulated on their surfaces and captured the shadows they cast, giving their reproductions within the photo book a sense of objecthood. By referring back to their status as physical objects—possessing their own mass and occupying their own space—I emphasize the significance of materiality and volume in our apprehension of a photograph. In every spread, the photographs float in space, echoing the rhythm and pace that I took as I wandered in the world and inviting viewers to do the same—to wander, to examine, and to discover these heavenly bodies in the minutiae of the world.

Follow Angelica on Instagram: @catchingsunlight_

©Anna Rotty, Paradise Waterfall, installation of double-sided pigment print photographs on paper and transparency film, light, photographs of Albuquerque bathtub, Feather River, CA, Scituate, MA, 2022

The University of New Mexico | MFA

I strive for the feeling of lifting up a rock along the shore to see what world is living underneath. Spectrals from a shoreless sea embodies the pleasure and anxieties linked to water. Having grown up in the Northeast, I am amazed by the arid desert landscape of my new home in the Southwest. I’m fascinated by the Rio Grande as a fluid being with a complicated history. Last summer, I was shocked to witness the river dry up as far north as Albuquerque. This year it is overflowing. I have lived in places that flood often, or burn due to wildfire due to failed infrastructure. In response to these experiences, I have conversations with my father who works for the energy utility in Boston. Using his words and my personal reflections as prompts, I reconstruct photographs in the studio, or within the landscape, that investigate the systems, both natural and built, that transfer energy and water from place to place. The piece Paradise Waterfall looms 10 feet tall, referencing a memory of swimming below a waterfall located in Butte County, California, near a site of failed energy infrastructure, causing one of the largest wildfires yet. Using materials like transparencies and mirrors, I invite movement through space and physical engagement, helping us slow us down, pay attention, and shift perception; treating imagery of landscape as active rather than reiterating a passive gaze. Tide Pool with Periwinkles & Suns, a photograph of the constantly changing intertidal zone, hovers horizontally, a few inches off the ground, allowing us to gaze downward into this fluid micro-landscape through the rectangular frame of the camera. I’m always looking for moments that access an emotional connection through light. I ask, how can we show land and water as fluid, reciprocal experiences, rather than as fixed representations?

Follow Anna on Instagram: @annarotty

©Tristan Sheldon, Working Clay, 2020

The University of Missouri | BFA Studio Art

Golem is an ongoing meditation on the conflicting and tenuous relationship between the built environment, the human body, and the natural world. As we relentlessly shape and mold the world to our will, we disrupt a complex and largely unseen environmental balance on which we depend for survival. The work portrays human intervention in the landscape as both reverent and destructive. Through the use of dramatic contrast in tonal range and material, as well as recurring motifs of touch and physical impression, the work suggests a relationship with the world that is as harmful and predatory as it is tender and nurturing.

Follow Tristan on Instagram: @tristan__sheldon

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Lorraine Turci: The Resilience of the CrowMarch 16th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Awards: Natalia Garbu: Moldova LookbookMarch 15th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Rayito Flores Pelcastre: Chirping of CricketsMarch 14th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Alena Grom: Stolen SpringMarch 13th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Louise Amelie: What Does Migration Mean for those who Stay BehindMarch 12th, 2024