Raymond Thompson Jr: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize: 1st Place Winner

“I see my work as an act of resilience;

it is a way to begin a personal healing process that counteracts the impact of generational trauma.”

It is with so much pleasure and excitement that we announce the 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize 1st Place Winner, Raymond Thompson, Jr. He was selected for his outstanding project, Appalachian Ghosts. He is working towards his MFA at West Virginia University which he will receive in 2021.

The jurors included Guanyu Xu – 2019 Student Prize Winner, Zora Murff- 2018 Student Prize Winner, Shawn Bush – 2017 Student Prize Winner, Drew Nikonowicz – 2016 Student Prize Winner, Elizabeth Moran – 2013 Student Prize Winner, Aline Smithson – Lenscratch Founder & Editor in Chief, Brennan Booker – Lenscratch Director of Special Projects, and Daniel George – Lenscratch Submissions Editor. We had a record number of submissions and the competition was fierce.

Raymond will receive a $1000 Cash Award and a feature on Lenscratch, a $250 cash prize from The Griffin Museum of Photography, a $500 Gift Certificate from Freestyle Photo Supplies, a $500 Gift Certificate towards a Los Angeles Center of Photography Workshop, a $500 Gift Certificate towards a Santa Fe Photo Workshop, a mini exhibition on the Curated Fridge, a collection of books from Yoffy Press, a collection of books from Kris Graves Projects, a year long mentorship with Aline Smithson, a Lenscratch T-Shirt and tote and a Supporting Level membership with CENTER.

This powerful body of work is presented with four different approaches to storytelling, each adding new considerations to “documented” African-American visual history. The work “challenges the political nature of archives and pushes back against the history of photography that has consistently been used to silence and erase black and brown bodies.” As he states, “Specifically, I’m looking at what has been left out of African-American visual history, which to date has mainly been documented with a colonial gaze. From this standpoint, I have sought to re/create work that has been informed by and made from historical documents and photographs.” I am thrilled to be in conversation with Raymond on October 1st, through the Los Angeles Center of Photography.

Raymond Thompson Jr. is a freelance photographer and multimedia producer based in Morgantown, WV. He currently works as a Multimedia Producer at West Virginia University. He is also pursuing an MFA in photography from West Virginia University. He received his Masters degree from the University of Texas at Austin in journalism and graduated from the University of Mary Washington with a BA is American Studies. He has worked as a freelance photographer for The New York Times, The Intercept, NBC News, Propublica, WBEZ, Google, Merrell and the Associated Press.

In the 1930s, migrant laborers came from all over the region to work on the construction of a 3-mile tunnel to divert the New River near Fayetteville, WV. During the process, workers were exposed to pure silica dust due to improper drilling techniques. Many developed a lung disease known as silicosis, which is estimated to have caused the death of nearly 800 workers. Up to two-thirds of those workers were African American. Besides a small plaque at the Hawks Nest State Park, which lists a significantly lower number than the actual number killed, there is very little to mark the site. There is also sparse visual documentation available about the event. There has been an effort to erase this tragic moment in history from the memory of West Virginia.

In Appalachian Ghost, I explore visual possibilities of what that time and place looked like, using primary-source materials to recreate the workers’ experiences in photographs. I have also recontextualized and re-presented archive photographs, originally made to document the construction of the Hawks Nest Tunnel dam and powerhouse. The few people caught in the photographic archive were often nameless and voiceless workers. Specifically, I’m looking at what has been left out of African-American visual history, which to date has mainly been documented with a colonial gaze. From this standpoint, I have sought to re/create work that has been informed by and made from historical documents and photographs.

In Twelve Men, I have cut out, enlarged and reprinted specific figures from the archive photographs. The 40×72-inch cutouts were created from two photographs appropriated from the West Virginia State Archives. In the two large group portraits, the anonymous photographer set his composition in the opening of the drilling wall inside the tunnel. In the photographs, some of the men posed looking directly at the camera, some posed with a playful swagger and some look to be still drilling at the wall. Behind the 20 to 30 workers, you can see the rock that would claim many of their lives. Throughout this process, I was intrigued by the individual figures from these photographs. I struggle to see actual facial details in the images. The images have a soft focus and at times look like they have been manipulated in the printing process. This fascination led me to cut out the images and to print them at human scale. The images where printed and mounted to 3/16-inch foam core for display. I was working with digital scans that were only big enough to create 8×10-inch images. I had to digitally extrapolate files to enlarge the figures to a human scale. This created a texture on the surface of the photograph that looks like digital noise, but the further you stand from the figures the details of the image start to emerge.

My research also focused on working with non-visual resources that inspired the creation of new works. I researched news clips, letters, poetry and other cultural resources looking for information that described the experience of working in the tunnel. I was particularly struck by a poem from Muriel Rukeyser’s book The Book of the Dead called “George Robinson: Blues:”

As dark as I am, when I came out at morning after the tunnel at night,

with a white man, nobody could have told which man was white.

The dust had covered us both, and the dust was white.

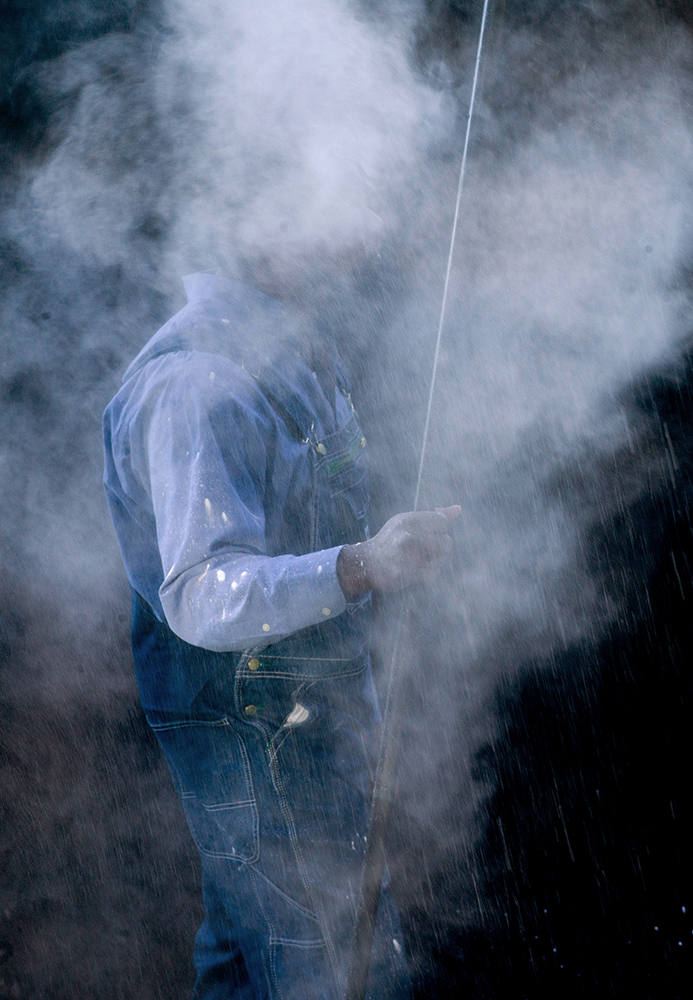

Rukeyser’s book, along with other primary-source documents, inspired a series of images that focuses on the silica dust that covered everything at the work site.

In my series, The Dust, I created a series of 24×30-inch photographs that featured black men performing gestures similar to images found in the Hawks Nest archive. I add layers of dust to obscure the men as they worked. I wanted to make images that were not possible to make in that dark tunnel, and I wanted the viewer to share in the experience of the Hawks Nest Tunnel workers. In addition, my piece, Tunnelitis, is a 24×30-inch triptych of hands covered in dust. With this work, I was also attempting to pull the viewer into the space of the tunnel workers by isolating a single element of recreation.

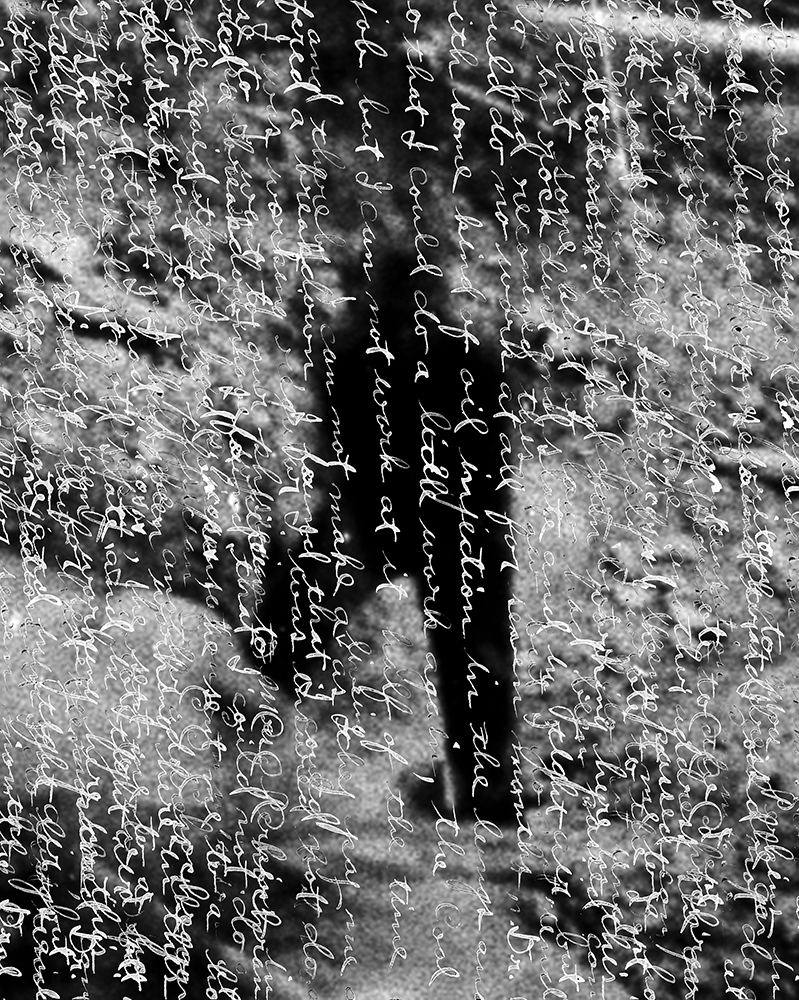

In my research, I found images that looked like they had been seriously manipulated in the printing process. This intervention and alteration of the documentary image shook my belief in the sanctity of the archive. One particular image shows a scene outside the tunnel. There are five figures in view, four workers and one manager wearing dress clothes. The four workers are completely removed and look like their exact shapes have been burned to black. The manager is the only one not removed from the image. In my piece, Erased, I combine cropped and enlarged cutouts of the blurred black forms with archive letters written by Hawks Nest workers describing the working conditions at the time.

Shawn Michelle Smith argues in Photography on the Color Line that archives have a power beyond the dusty storage rooms that hold them. “Once an archive is compiled, it makes a claim on history, it exists as a record of the past. The archive is a vehicle of memory, and as it becomes the trace on which a historical record is founded, it makes some people, places, things, ideas, and events visible, while relegating others, through its signifying absences, to invisibility. In this sense, then, archives have an ideological function not only in the moment of their inception but also across time, for they determine in large part what will be collectively remembered and how it will be remembered.”

She also argues that it is the archive where a counter narrative can be developed. In this way the archive can be a site for resistance against historical narratives that would erase minority communities labor in developing America’s cultural heritage. “Archives train, support, and disrupt racialized gazes, infusing race into the very structures of how we see and what we know.”

Beyond the archive, the black body in photography has a long and contentious history.

Photography was invented in the early 19th century. In America, the medium emerged in a political and social climate that was especially fearful of blacks’ interrogation of the social order that enslaved them. Louis Agassiz, an anthropologist, used the medium to make claims that argued that there were biological differences between the races. Carrie Mae Weems pushed back against this narrative by directly appropriating these images from the Getty Museum archive, in her series From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried. Brian Wallis, author of “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes,” argues that “Weems saw these men and women not as representatives of some typology but as living, breathing ancestors. She made them portraits.” I was inspired by Weems’ work while I was working on Appalachian Ghost.

I was also inspired by photographer Cristina De Middel’s book Afronauts. In the series, she used primary-source documents about a proposed Kenyan space program to create a series of images. This work helped me see the potential of archives to mine for new visual approaches to image making.

With this work, I sought to challenge the political nature of archives and to push back against the history of photography that has consistently been used to silence and erase black and brown bodies. For as long as I can remember, I have been bombarded by waves of stereotypical narratives of black people and their role in American society. One of the reasons I decided to pursue an MFA was to figure out how to use those narratives to rethink, remake and redefine the scope of the black experience in this country. I see my work as an act of resilience; it is a way to begin a personal healing process that counteracts the impact of generational trauma.

1.Michelle Shawn Smith, Photography on the Color Line : W.E.B. Du Bois, Race, and Visual Culture. A John Hope Franklin Center Book. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

2.Ibid

3.Brian Wallis, “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes.” American Art 9, no. 2 (1995): 39-61.

Tell us about your growing up and what brought you to photography?

I grew up outside of Washington D.C. in the Northern Virginia area. I’m lucky that I grew up in such a diverse region. I didn’t know this then, but looking back now at my elementary school class photographs, it looks like a mini United Nations. I feel like for that short part of my life I was mostly shielded from racism. This allowed me a freedom from the immediate impact of growing up in a racist culture during one of the most traumatic moments in modern times, the War on Drugs.

Watching the War on Drugs unfold on my TV screen in the 1990’s and early 2000s left a huge influence on my sense of self and on what I, as an African American male, can achieve in life. One of the reasons I came to photography was because I wanted to directly wrestle with what it means to be black in American society.

We are always considering what the next generation of photographers are thinking about in terms of their careers after graduation. Tell us what the photo world looks like from your perspective. What you need in terms of support from the photo world? How do you plan to make your mark? Have you discovered any new and innovative ways to present yourself as an artist?

One of the reasons I decided to attend graduate school was to help me break out of a photojournalism mindset in which I was trained. So as I peak at the photography world from outside photojournalism, I see a lot of overlap. I’m starting to see the walls that separate all of photography’s genres as artificial. From this point of view, I think that there is a lot of opportunity, but it’s going to require new ways of thinking as the traditional paths to a career in photography continue to dry up.

I hope to make my mark as an artist and an educator. I also want to be a part of the ongoing conversation to understand and possibly rewrite photography’s complex relationship with blackness.

I don’t think I have discovered any new or innovative ways of making images. Graduate school has been a humbling experience. There is so much I still need to learn. I was able to attend the opening of the 2020 Fotofest in Houston before it was shut down because of Covid-19. This year’s theme focused on African photography and I was blown away at how many of the photographers I had never seen or studied in my photography history course. It actually left me a little frustrated. But the experience has helped me open a new line of inquiry to understand the influence of photography on the African and African American diaspora in a deeper way.

Your project uses archives not only for research but for the potential of questioning history from the perspective of the black gaze, a gaze that interprets these documents and photographs in a very different way. Can you speak to that?

Through my research I have come to learn that archives are political things. Archives are collections of primary source materials. People, organizations and states, entities that are political by nature, collect primary source materials to provide evidence of existence. Shawn Michelle Smith argues in Photography in the Color Line that the function of archive was to determine what and who should be remembered as part of America’s collective memory. “If one cannot or does not produce an archive, others will dictate the terms by which one will be represented and remembered; one will exist, for the future, in someone else’s archive,” wrote Smith. When you take Smith’s notion and look a little deeper at the organizations that compiled archives you can find ulterior motives. In some cases you can trace the threads of an archive that weaves in and out of the political, social and financial interest of white supremacy and capitalism. For example, the Hawks Nest Tunnel archive is composed of primary sources materials donated by the corporation that built the dam project. The Hawks Nest Tunnel photographs that make up the public’s understanding of the event were made from this white supremacist, capitalist patriarchal gaze. But for me, the archive is a double edged sword that can be interpreted in different ways. The archive exists as an important site to reimagine and disrupt the white gaze in visual culture. This project was an attempt to reclaim a part of this history.

How did you come to the story?

I first came to the story from Muriel Rukeyser’s book of poetry The Book of the Dead. Rukeyser traveled the region in the mid-1930’s and reported on the disaster. The output of her reporting was a book of poetry. The book’s introduction written by Catherine V. Moore, was also important in sparking my interest in the story. The essay written in a travelogue form reinforced the idea that the region had mostly forgotten about the people who died in the name of progress. But, what really captured my attention was actually visiting the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel Worker gravesite. The once forgotten cemetery, which sits on the side of a Wet Virginia byway, holds three dozen nameless bodies marked by ply wood crosses. While I was standing on the hollow grounds something reached out and hooked me. I knew I needed to make work about what happened to these men and women.

One of the powerful statements you shared was that when everyone was covered in dust, skin color disappeared, and it reminded me that the dust of who we are at the end, for example, if we were cremated is also a dust of no color and it’s an important idea. Tell us about your concept of approaching the project in multiple ways.

I think my approach stems from trying to be as open as possible to making work for this project. To begin with, I had a series of different primary source materials to work with, Muriel Rukeyser poetry, archived photographs and documents, newspapers and magazines reporting, and all the physical Hawks Nest sites themselves. I found over time that each primary source material needed a different approach. The project is broken up by two different concerns. The first was how do I address the lack of images produced that show workers in the space. I wanted to imagine what it was like to be in the tunnel surrounded by dust. The second concern was how do I overcome the way that the Hawks Nest archive was constructed to minimize the workers that were actually photographed. The Hawks Nest archive was about documenting an industrial process, the workers were never a concern.

My next step is to complete my MFA thesis work. I feel it’s been challenging to make art through the explosion of Covid-19 and the Movement for Black Lives. I’ve had to really fight the urge of my formal training to return to the immediacy of photojournalism. I had to stop and think for a time about what was the most significant way to contribute to the importance of this moment. I realized that my real work will unfold over a longer period of time than a protest and that I needed to continue on my current path.

I’m currently tracing the edges of my family’s history, from the perspective of my grandfather. I’m finding that this history is made up of a combination of facts and half-truths. In my search, I have to navigate walls built of memory, myth and incomplete archives, which works to obscure much of that history.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Amrita Stützle: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Winner Honorable MentionJuly 29th, 2020

-

Leah Schretenthaler: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Winner Honorable MentionJuly 28th, 2020

-

Hannah Altman: The 2020 Student Prize Winner Honorable MentionJuly 27th, 2020

-

Lindley Warren Mickunas: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable MentionJuly 24th, 2020

-

William Camargo: The 2020 Lenscratch Student Prize Third Place WinnerJuly 23rd, 2020