THE FOTO AWARDS PRESENTED BY LAS FOTOS PROJECT: Chrystal Ding in Conversation with Anna Grevenitis

Las Fotos Project was launched to provide opportunities for those who are both systemically and socially silenced to make themselves heard

This week in honor of Latinx Heritage Month, we are celebrating a wonderful organization in Los Angeles, the Las Fotos Project, and The Foto Awards taking place on October 22, 2022. Today we celebrate The Self-Expression Award Winner, Chrystal Ding.

Las Fotos Project’s mission is to elevate the voices of teenage girls through photography and mentoring, empowering them to channel their creativity for the benefit of themselves, their community and future careers. The organization was founded in 2010 to introduce teenage girls to the transformational power of photography and advance positive change in the surrounding community.

Born in China and based in the UK, Chrystal Ding is a research-led artist and writer who works with photography, text, personal archives, and machine learning to explore the impact of past (trauma) and future (technological advancement) on identity.

Chrystal read English at the University of Cambridge, and holds an MA in Photojournalism & Documentary Photography from London College of Communication (University of the Arts London).

Her work focuses on the intersections of science, culture, and the individual, and has been published by the BBC, The Guardian, The Telegraph, the Royal Photographic Society Contemporary Photography Journal, and PHmuseum. She was one of 209 female photographers selected to contribute a portrait to the ‘209 Women’ project in 2018, commemorating 100 years since women got the vote. In 2019 she was awarded the Rebecca Vassie Memorial Award, which funded her work Yours is Going to Be Healed As Well about genocide survivors in Rwanda taking part in group counseling.

From 2017-2019 she worked with the Wellcome Genome Campus to produce Genetopia, a self-published book about 23 people who had done DNA tests and an exploration into what genetic testing means for the individual. In 2018 she co-founded Ixy Labs, a pop-science research and discussion series about private life in the time of AI.

Her current work uses machine learning as a tool for self-expression, and she is interested in issues of embodiment in the machine age.

Follow Chrystal Ding on Instagram: @chrystal.ding

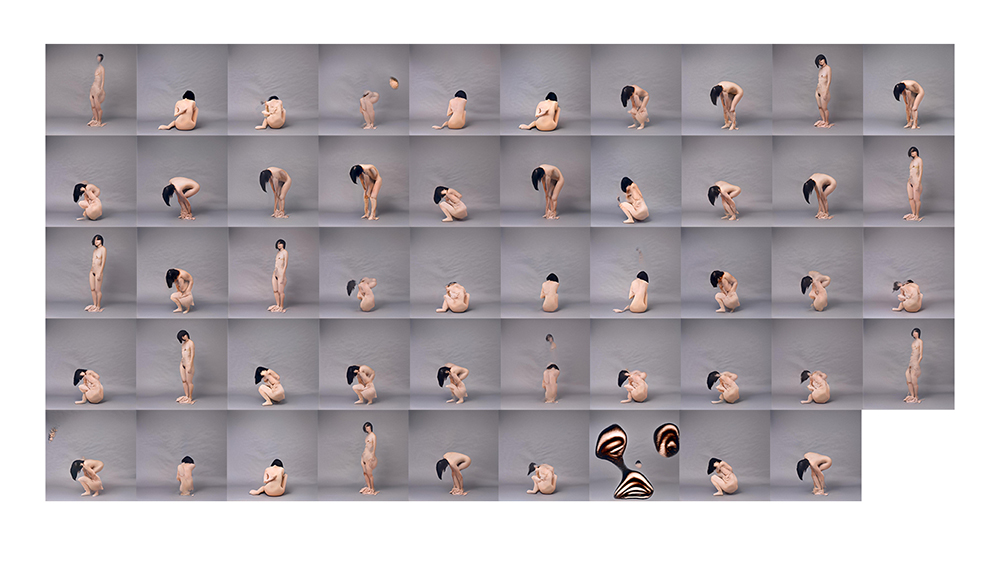

© Chrystal Ding, ‘Performance IV’ from Bits and Pieces, in which a GAN recreates a human performance of a mental health crisis. ‘Performance IV’ recreates a recital of a decade of mental health records.

I am interested in things that ‘other’ us – be they science, culture, each other, or ourselves. My work is an attempt to give space to these things – space to capture, to explore, and to ask questions. The methods I rely on – image-making and writing – can be described as inherently othering. They force the author to adopt a perspective (first person/third person, subject/photographer) and in so doing they make it impossible to tell a story without addressing the complexity of the story being told. In this, they become useful tools for exploration – they invite questions rather than answers. If I can wield them well, they create space for thought. If my work may be said to have an objective it is that – to think something through, and to invite thought. In that sense, the work is rarely conclusive, sometimes shared, and always in progress. -Chrystal Ding

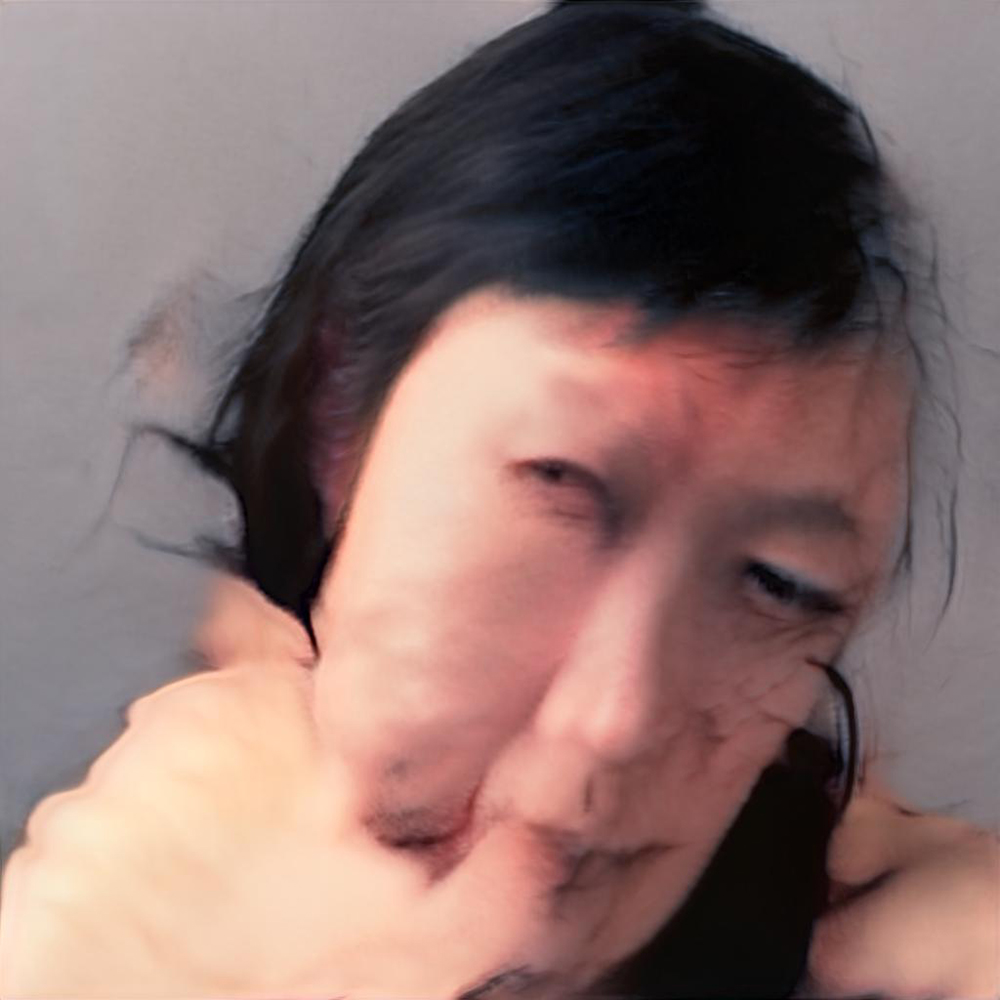

© Chrystal Ding, ‘Performance III’ from Bits and Pieces, in which a GAN recreates a human performance of a mental health crisis. ‘Performance III’ is a recreation of depression.

Anna Grevenitis: As an adoptee genetic testing has had a crucial place in the search for my identity. A few years back my husband gifted me a 23 and me dna kit for my birthday and I was very eager to spit, mail and discover more about myself. After all that there was really nothing flabbergasting to uncover, but in an odd way, the ordinariness of my discovery grounded me and became an integral part of my process to find my roots. Can you tell me what started you in your artist quest on the story of genetics and if completing your project Genetopia changed your way of seeing yourself in the world.

Chrystal Ding: Your story resonates a lot – I think that when it comes to consumer DNA testing, for every person who uncovers something new, there’s a person who discovers who they already were, and to me that’s a good reflection of the inherent tension of being a person. It’s an iterative process, and continuity is as valuable to recognize as change.

That’s kind of where my artist quest began too. I come from a family of scientists, and I’m not a scientist, which always left me feeling like my view of the world was somehow not quite right. But at the same time, science has shaped a lot of my experience. As a kid, I spent a lot of time in the lab where my mother worked, waiting for her to finish her day. Some of my fondest memories are of liquid nitrogen being poured, 3D printed metal, and images from electron microscopes of metal alloys – those were the images I grew up with, not photographs, and they were beautiful. They always seemed to reveal something more, something secret – they made invisible structures visible. But at the same time, they were just revealing reality through a different ‘lens’ so to speak.

At the beginning of the project, I did a 23andMe test too. Like you, I didn’t discover anything flabbergasting. But when I started interviewing people about their experiences, I discovered that they had really different views about what they considered private, specifically what they considered too private to share. Some people were completely open books and delighted to share what they had found. Others did a lot of talking to their families and weighing up how much they wanted their story told versus how much it would require them to reveal, and not only about themselves. Because that’s the thing – spitting in a tube is a very clinical act, an individual act, one that you can do just sitting in front of the TV, but the stuff that you find out goes so far beyond the individual – it ends up being about family, sometimes hypothetical future family. And I think almost everyone I spoke to wanted to make sure their families were involved in their decisions with the project – that was really reassuring actually. I thought the weight of their decision-making was so much more telling than any story I could pull together, so that’s what it became – interviews directly in the participants’ own words, guided by whatever material from their own lives they wanted to share to tell their stories. I became more of a facilitator than anything else, which also fit well with my nature. I like asking questions, and I don’t mind leaving with more questions than answers.

AG: I am fascinated by the behind the scenes of this project. Just like Schenectady New York by Andy Kaufman and Gordon Mata Clark before him (who is featured in the diary!) Your project Stanley Street shows more than just the inside of a house. It is as if we are given the script of the character and the stage direction. Please tell me how you came to find the house and what was your process while executing the project. Why did you feel compelled to tell the story of Stanley Street?

CD: I have to preface this by saying that moving to Australia was simultaneously one of the dumbest and best things I’ve ever done. I had a full-blown eating disorder at university, and in the middle of my final year exams I received this letter offering an incredibly detailed and well-thought-through treatment plan that involved me staying in my university town and attending lots of group therapy sessions in clinic (enough that I would have struggled to hold down a job), and I remember thinking to myself when I got this letter, ‘I did NOT work this hard just to graduate into an eating disorder clinic’. So I was feeling really annoyed and self-righteous about this when I went to get a coffee and the barista asked me, “What are you going to do when you graduate? Are you going to go and work in a bank like the others?” and in this stupid naive fury, I just spat back, “I don’t know. Maybe I’ll move to Australia and work on a farm or something.” He did me the wonderful accidental favour of saying “You can’t do that. People don’t just move to Australia and work on a farm.” So I basically ran back to my room, applied for an Australian visa, and woke up to realize that it had been approved.

Then the fear set in – was I really about to pack up my life and my eating disorder and move to the other side of the world? I was stubborn, so the answer was yes. But romanticism aside, the barista ended up being right – I didn’t work on a farm. But I did move, and I found a job selling pianos, and I devoted myself to learning to eat from scratch. For what it’s worth, I would not recommend this approach – it was entirely irresponsible. I was completely lost. (My journey with eating disorders certainly wasn’t fixed by one trip to Australia – there was a lot of therapy in the years that followed.)

But finding 12 Stanley Street was really a lot of the reason I didn’t just fall off a cliff entirely. It was just a regular ad online for a spare room in a house that was full of people who were also lost, and a landlord who created a space where we could all be safe to experiment and – as corny as it sounds – ‘find ourselves’. And those people – I loved them for it. I loved what we had together. I loved how our journeys overlapped in that time and place, and I knew that once we moved on we’d forget, and I didn’t want to forget. So I messaged friends in Australia asking them to send me back things I’d left there, I combed through all those photos that I’d taken with no purpose in mind, all the correspondence I’d written and received – I searched for anything that would capture the feeling I felt when I was there, and then it was a process of curation. I was trying to piece together a snapshot – a love letter of sorts – of being that age, that blend of brazen and idiotic, and having an adventure.

AG: Your background study in photojournalism and documentary shines in the series Second Youth. As a viewer we are allowed to look in scenes that are usually closed off to us, outsiders. The closeness to the smiles, the richness of fabrics and colors: Everything is there for us to revel in something that we usually would not be privy to. One of the subjects is quoted saying “It’s not been easy for us…we’ve got by all these years with our friends” How do you wrestle with your identity as a Chinese born UK based artist? Does this quote at the end of your series echo a personal feeling?

CD: It’s so strange to me that when you say ‘outsiders’ and you mean – entirely accurately – the viewer, not the migrant. To this day I sometimes walk past a mirror and think to myself ‘oh wow – there’s a Chinese person!’ We’ve all got identity-based baggage, and mostly it’s just part of who we are, but there are moments where our ‘otherness’ bumps into what’s considered ‘normal’ and it’s like a jolt that forces us to revisit the questions we thought we’d already answered. For a long time, I think I wanted to achieve some sort of ‘100% British’ benchmark as a way of never having to be othered again – I studied English literature as my Bachelors degree, thinking that somehow that would do it. Like ‘if I know Shakespeare, then nobody can accuse me of not belonging’. It’s obviously all a fallacy – nobody’s identity is that reductive. But there are certainly moments when people lean on the reductive interpretation because it’s simpler. I’d consult mental health services, they would see I was Chinese, fix a narrative built on a stereotype in their heads, and any attempts I made to shift that narrative would completely fail – conversation over. It’s like they’d land on one correct assumption and completely miss the bigger picture. Or when people learn that I moved to the UK when I was 3 and they say “Oh so you’re basically English then,” and I stop myself from saying “Well not really… I spoke Chinese at home, my entire cultural reference was Chinese, I went to Chinese school as well as Western school, and I mostly socialised with other Chinese kids.” There are worse examples too. But the reality is: it’s the same in reverse. You, too, will overlook other people’s stories and be reductive without meaning to, so try and at least learn from your own experience – be curious. Intention matters, as does self-correction. “It’s not been easy for us” – most of the people I’ve ever met would say the same.

AG: When I first looked at your work in progress I was fascinated by the stark difference between them: one, Bits and Pieces, is a very personal series of self portraits and the other, Yours is going to be healed as well, an intimate documentary style series on survivors of the genocide in Rwanda. But as I looked closer I realized that indeed these are part of the same story: story of personal survival, of visibility, of humanity. How do you invite a new project into your life? What is your process once you decide on a project and how much time do you allow for each series? When do you know a project is finished? Finally what advice would you give to young, starting women photographers?

CD: I’m so relieved to hear you say that! I often worry that people will look at my work and think ‘what on earth is this person doing jumping between these things?’ To me, the thread is continuous, and I’m always trying to just create a space where the differences can meet. You phrase it so well – ‘invite a new project into your life’ – that’s exactly what it is. An invitation. It bubbles up in a moment of feeling, and a moment of desire. And then begins the research. I throw myself into books and papers – typically for something like two years – before I start making images. It’s probably too long, but it’s a product of a desire to be rigorous, and an anxiety around the handling of other people’s stories, and depicting reality. I plan a lot, but the trick is to leave enough space for serendipity – because until you start making the work itself, you don’t actually know what the story is, you’re just planning for a version that you believe is likely to be the one that is ‘true’.

I definitely take too long to finish projects – a huge part of that is life needing to be lived. I beat myself up for this a lot, but at the same time I don’t like to rush thinking, digesting, and marinating time – you only get one shot to say ‘this is the story I’m telling’. And once you start putting the work out there, you’re going to get a lot of opinions – some useful, some not. Either way – story’s out, and it’s not just yours anymore.

My advice to young people would be – take time to develop your craft and your instincts. One of my biggest regrets is that I’m nowhere near as good a photographer as I’d like to be, and I think a lot of this was lost to time not spent on that particular craft, but it was also because I’m an image-text hybrid person, and I was always splitting my time with the crafting of words and I don’t regret that at all. Even now, I make my living as a Writer not a Photographer – and I love it. And that’s okay – I’m not cheating on photography (or vice versa)! It took a surprisingly long time to acknowledge and accept that – I don’t think I’m fully there yet either. But the point of taking time, for me, is this: at the end of the day it’s your particular confluence of craft and instinct that is you, so figuring out where you stand with yourself on those things – what you’re prepared to throw away in favour of growth, and what you want to hang onto because it’s the stuff only you can bring to the work. That’ll become your process, and while the work may change, topics change, the tools you use change, the world itself changes – that’s the bit that stays consistent. That’s the bit that’s you.

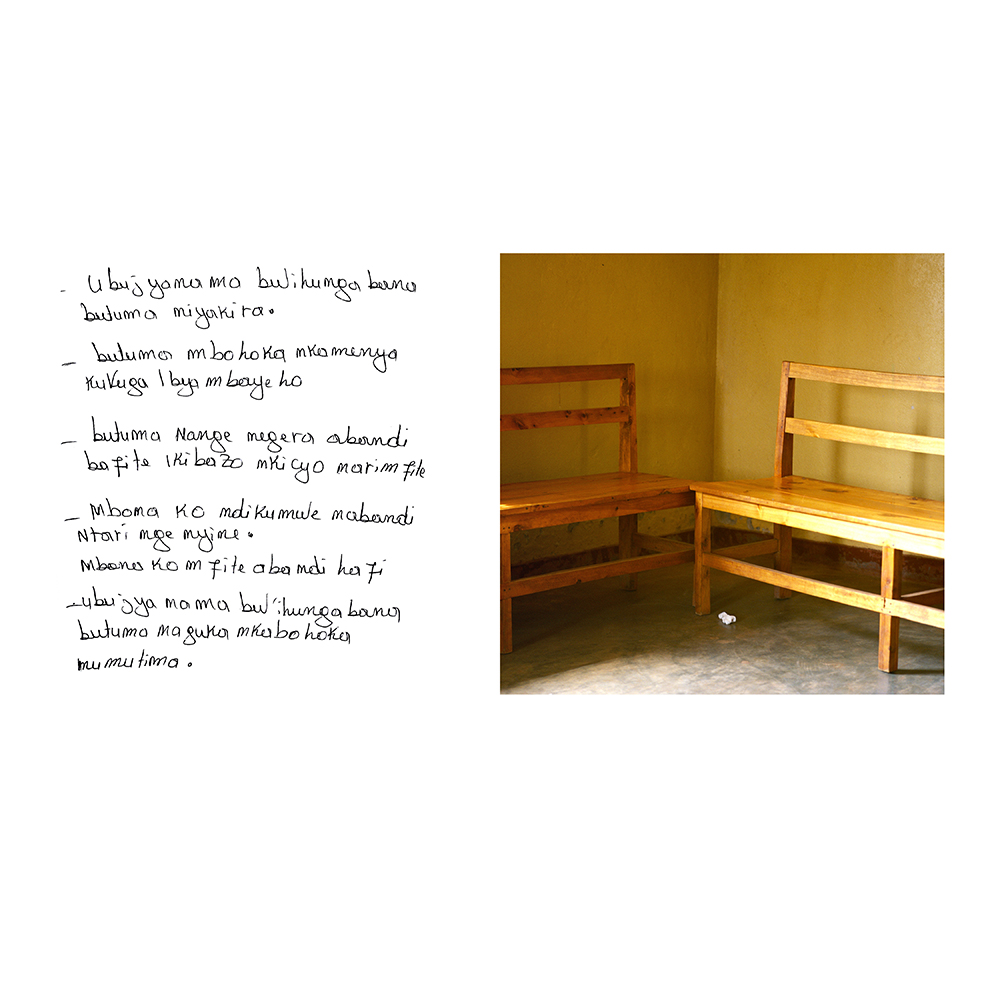

© Chrystal Ding, Photograph of a tissue left after a counselling session for genocide survivors in Rwanda. Accompanying the image – a survivor responds in writing to the prompt ‘What is the role of counselling in your life?’ Translation: Counselling helped me accept myself. Helped me to feel free to tell what happened to me. Helps me to reach out to those who have similar problems like the ones I had. Helped me to know that I am not alone, instead I have other people around me. The role of counselling awakens and sets my heart free.

© Chrystal Ding, Sunset over Kigali, accompanied by a genocide survivor’s written response to the question ‘What is your dream?’ Translation: ‘To reach another level.’

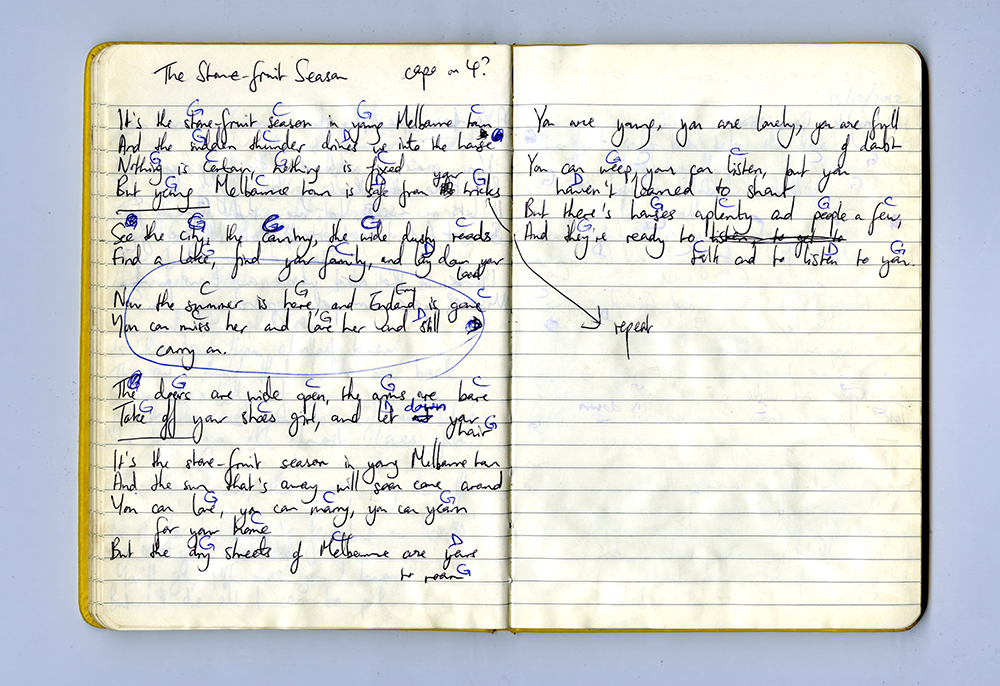

© Chrystal Ding, Lyrics and chord notation for a song written at 12 Stanley Street in Australia in 2012. Published in 12 Stanley Street. 2017.

Originally from France, Anna Aude Grevenitis is a visual artist based in Brooklyn, NY. For her work, the act of performing is an important step in image making. Drawing on the experiences of the domestic to inform her daily practice, she uses her home as a stage and her body and the body of others in her familial sphere as characters in order to deliver, in the photographs, the essence of what she wants to express about motherhood and the self. Nowadays she divides her time between research and creation, and she is interested in building long term projects in photography as an act of establishing visual memory and engaging in social visibility.

Follow Anna Grevenitis on Instagram: @annagrevenitis

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Lorraine Turci: The Resilience of the CrowMarch 16th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Awards: Natalia Garbu: Moldova LookbookMarch 15th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Rayito Flores Pelcastre: Chirping of CricketsMarch 14th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Alena Grom: Stolen SpringMarch 13th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Louise Amelie: What Does Migration Mean for those who Stay BehindMarch 12th, 2024