Wendel White: Storytellers

How we experience an image has largely to do with light, tonality, and composition. Even when dealing with depictions of chaos and violence, artfully made images have a way of fooling our senses although we may logically know better. What we are left with is an ineffable dissonance. While it would be easy to view this discord of the senses as a limitation of the medium it’s also an opportunity for practitioners to make photographs that do more than describe a scene’s exterior.

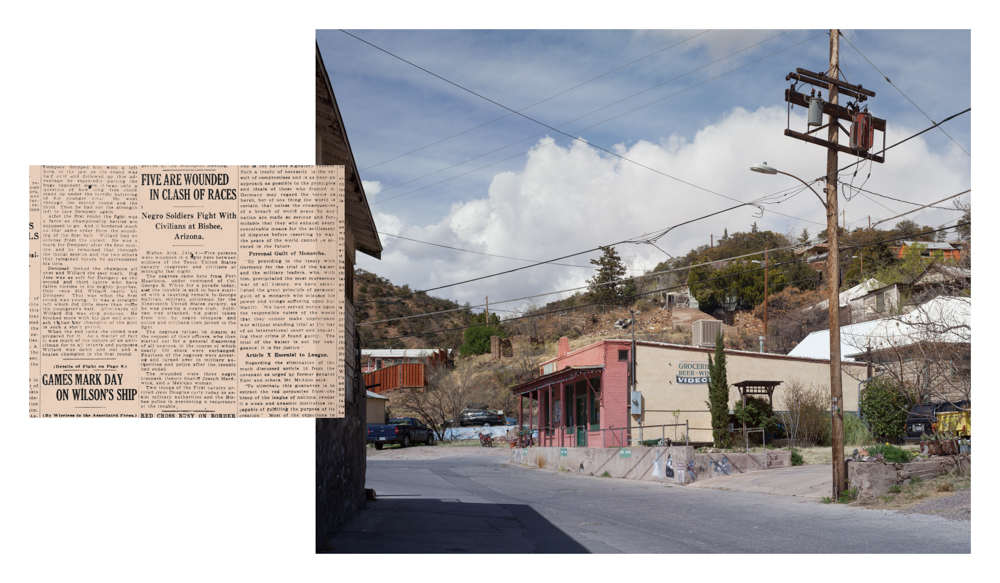

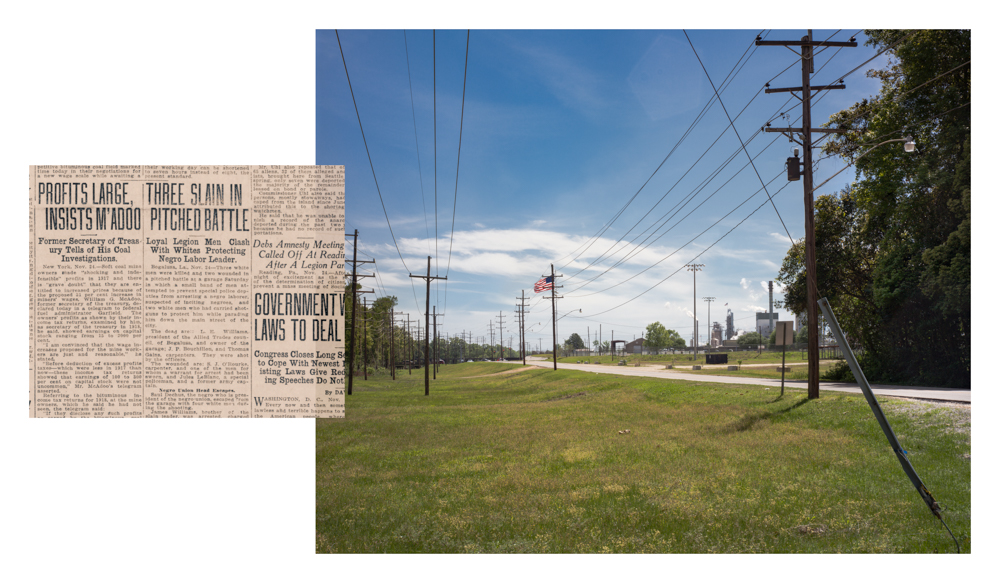

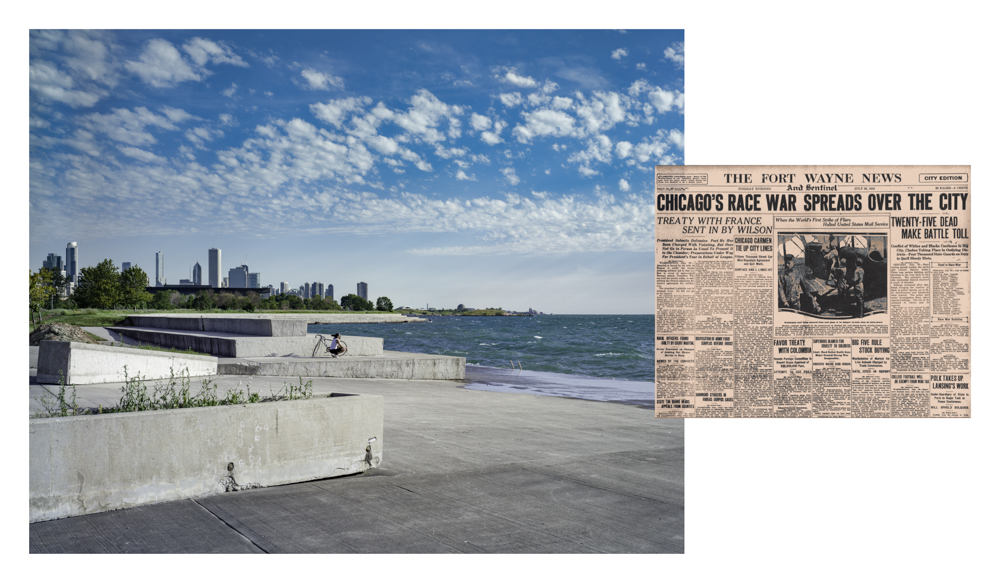

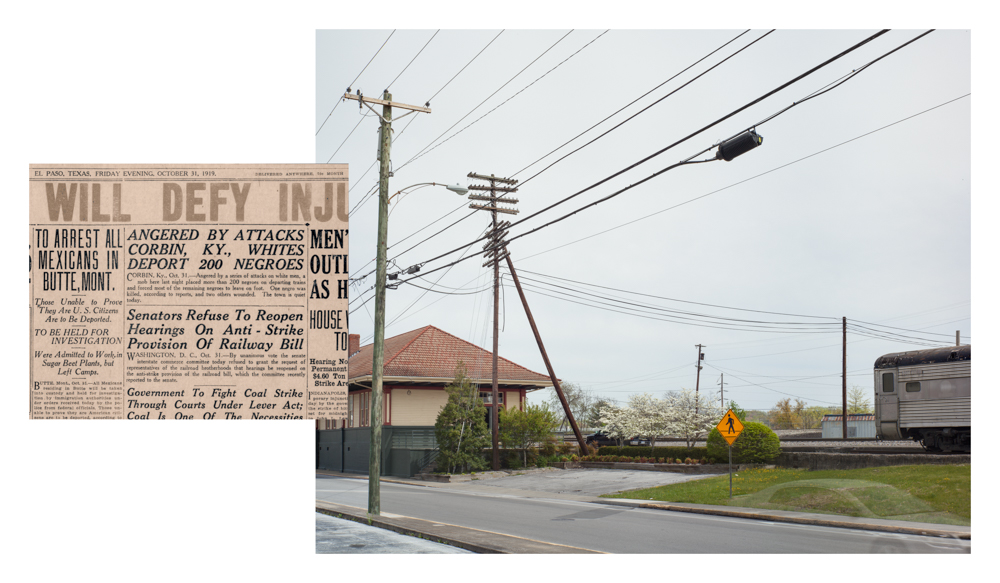

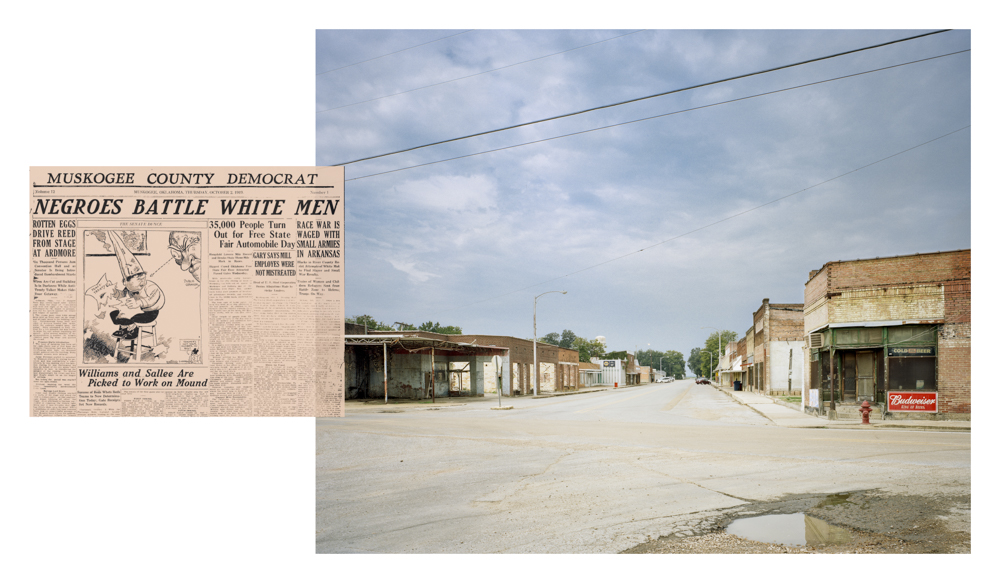

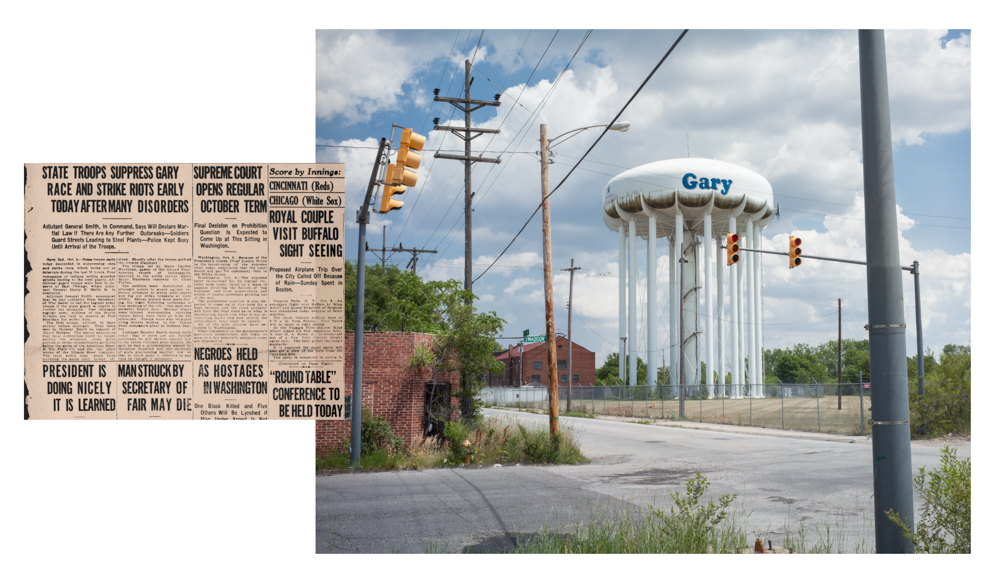

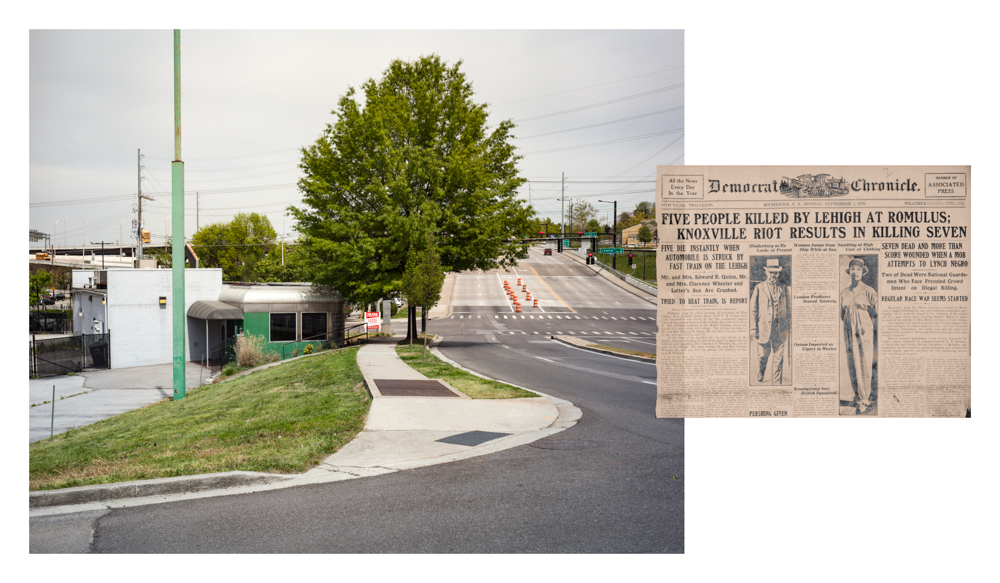

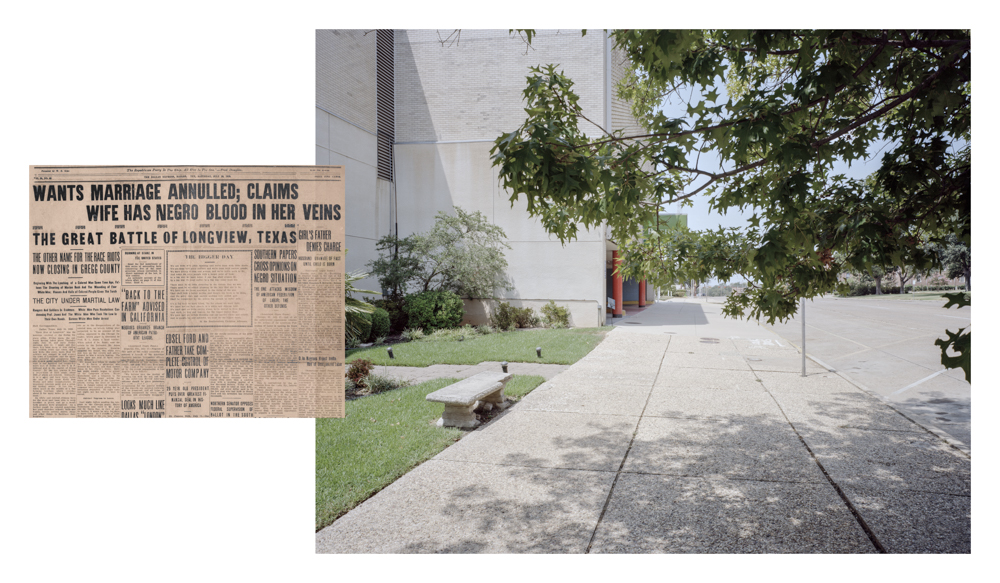

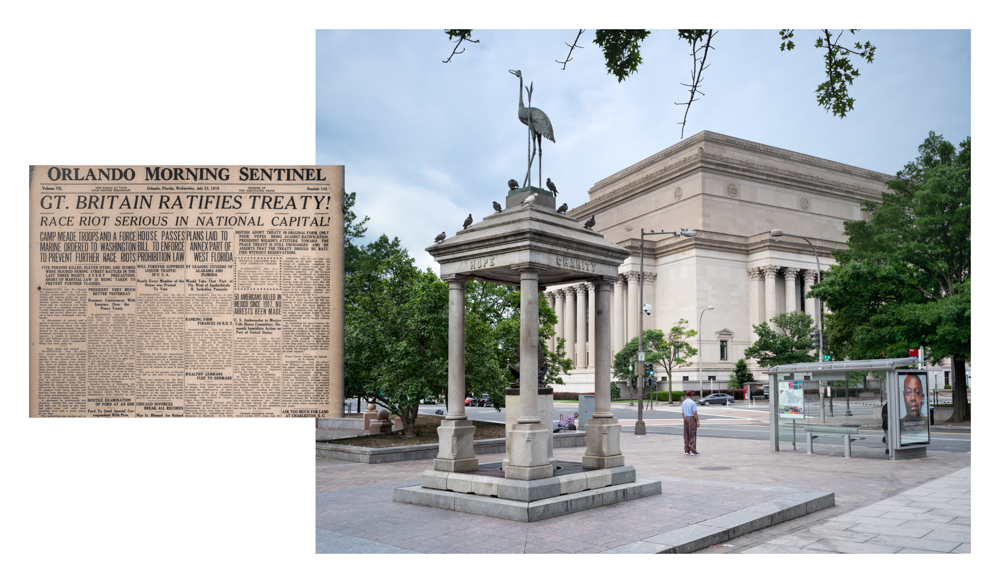

Enter Wendel White, a New Jersey based photographer whose series Red Summer pushes the boundaries of how we as viewers experience landscape. Made over the course of several roadtrips, White traveled to prominent locations of racial violence which targeted the black community between 1917 and 1923. This tumultuous period of unrest and upheaval was positioned between the Civil War and peak of the Civil Rights Era by roughly 50 years on either side. The resulting images are disarmingly serene. A partially deconstructed dock stretches into a gently rolling stretch of water on the outskirts town. Sleepy urban centers and vacant roadsides beget a world outside of time. The few figures that we encounter are turned away from White, seemingly on their way and unaware of his presence. If it weren’t for the revelation of a modern shopping center one could lose themselves to the ageless perpetuity of these works.

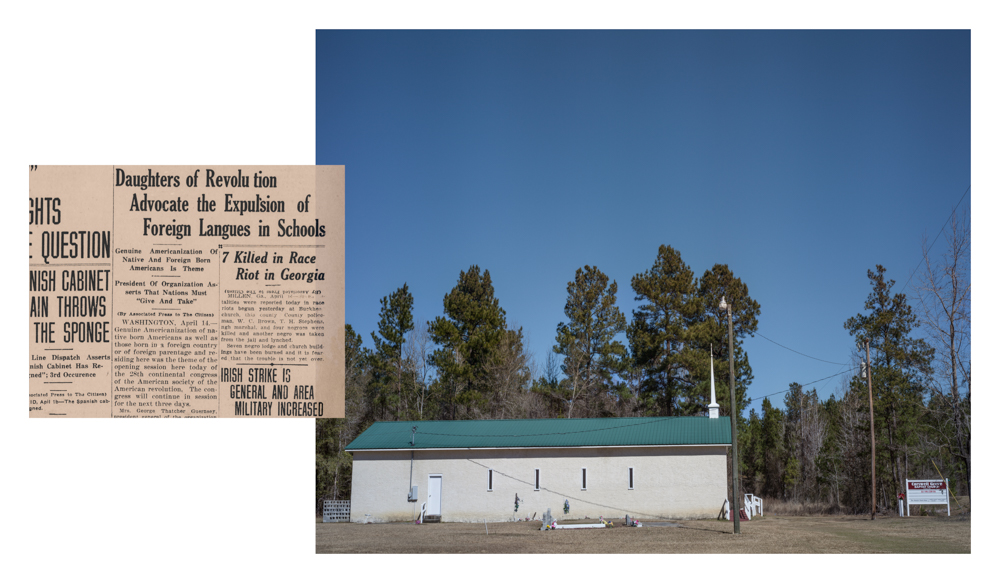

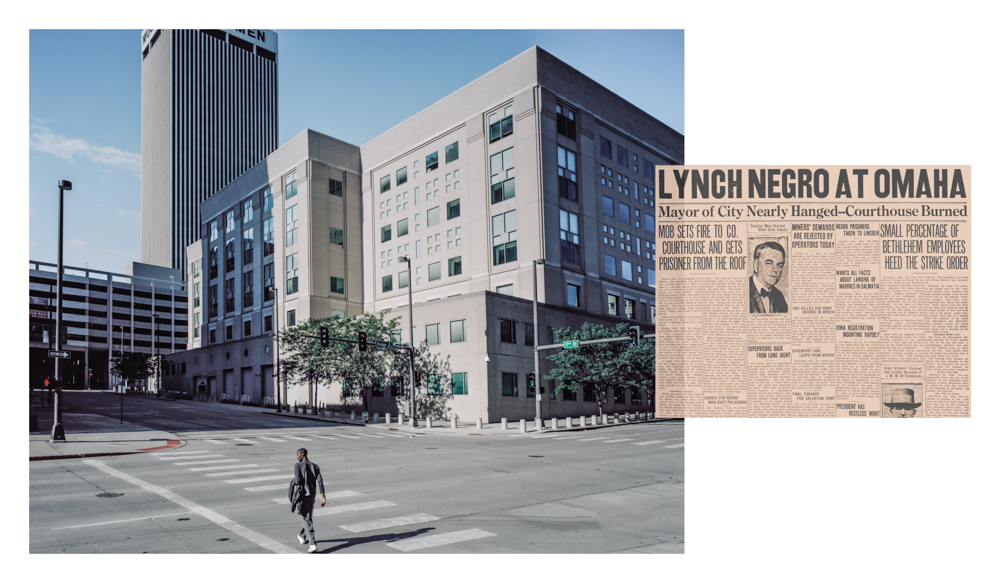

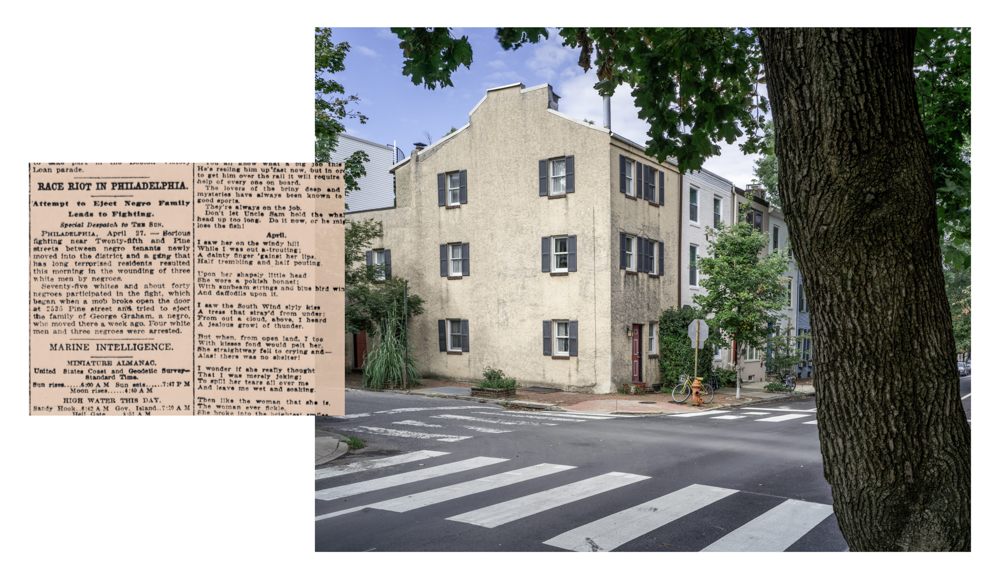

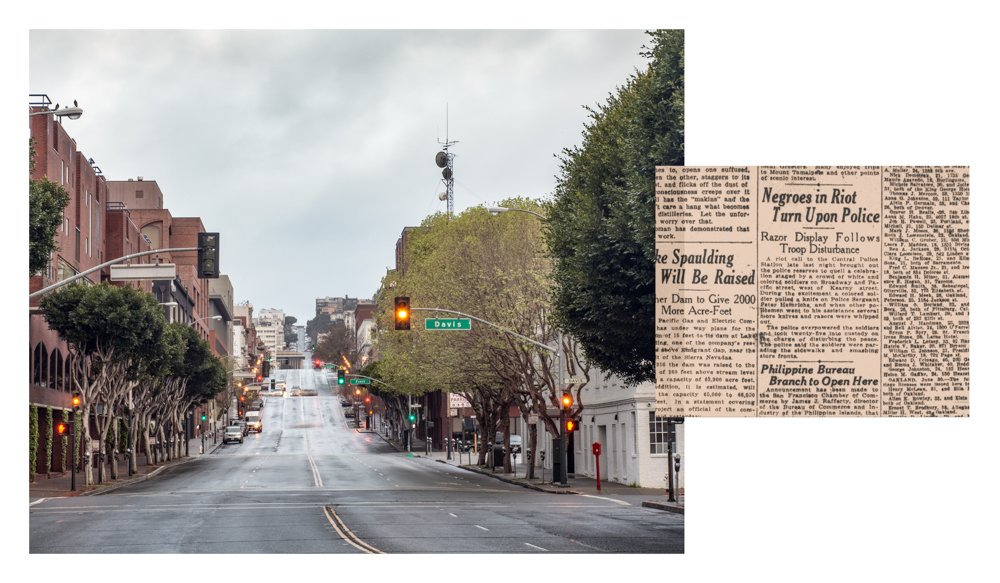

However, look beyond the frame and you’ll find juxtaposed archival newsprint that stands in opposition to the previously conveyed tranquility. These headlines proclaim “Six Are Killed Many Are Wounded In Charleston Riots,” “Five Are Wounded in Clash Of Races”, and “Chicago’s Race War Spreads Over The City”. These contrasted pairings are an urgent reminder of the countless realities beyond our own lived experience. A place of respite for one was a place of bloodshed for another. Through decades of systemic erasure these histories are forgotten and new worlds grow over. It is through this forgetting that we repeat ourselves and atrocities of the past become contemporary. White’s work plays with this timeline to great success, highlighting past and present and joining them in visual form. Through this series one comes to realize that the landscape in and of itself remains objective even as centuries of evolving human influence wash over.

Wendel A. White was born in Newark, New Jersey and grew up in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. He was awarded a BFA in photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York and an MFA in photography from the University of Texas at Austin. White taught photography at the School of Visual Arts, NY; The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, NY; the International Center for Photography, NY; Rochester Institute of Technology; and is currently Distinguished Professor of Art & American Studies at Stockton University.

He has received various awards and fellowships including a John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in Photography, three artist fellowships from the New Jersey State Council for the Arts, Bunn Lectureship in Photography and grants from Center Santa Fe (Juror’s Choice), the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, and a New Works Photography Fellowship from En Foco.

His work is represented in museum and corporate collections including: Duke University; the New Jersey State Museum; California Institute for Integral Studies; The Graham Foundation for the Advancement of the Fine Arts; En Foco, New York, NY; Rochester Institute of Technology; The Museum of Fine Art, Houston; Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL; Haverford College, PA; University of Delaware; University of Alabama; and the NYPL Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, NY.

White has served on the board of directors for the Society for Photographic Education, three years as board chair. He has also served on the Kodak Educational Advisory Council, NJ Save Outdoor Sculpture, the Atlantic City Historical Museum, and the New Jersey Black Culture and Heritage Foundation. White was a board member, including three years as board chair, of the New Jersey Council for the Humanities.

Recent projects include; Red Summer; Manifest; Schools for the Colored; Village of Peace: An African American Community in Israel; Small Towns, Black Lives; and others.

Red Summer

The Red Summer portfolio represents the stories of various locations in the American landscape where racial violence (often characterized as “Race Wars” at the time) erupted between 1917 and 1923. These years of conflict reveal several aspects of racial anxiety that inform our contemporary experience, including, though not limited to; racism, fear of violent black revolt, lynching, poverty, mass incarceration, and competition for employment. The term “Red Summer” was first used by James Weldon Johnson to describe the violent attacks against black communities during 1919.

Though the events of the early twentieth century seem to be remote and fading apparitions of an American past; my work is concerned with the power and influence of our shared historical narrative upon the present. The upheaval of Red Summer occurred approximately fifty years after the American Civil War, fifty years before the height of the Civil Rights Era and three centuries after the first enslaved Africans arrived in English colonies that would become the United States.

The project combines photographs of the contemporary landscape made at or near the site of racial conflict with fragmented selections of contemporaneous newspaper reporting (1917-1923). In many cases the newsprint images include the surrounding stories or advertisements. The combination of the landscape photograph and the reproduction of newspaper fragments (which invade the contemporary with a narrative from the past), is a rupture and a conversation on the timeline between past and present.

The conceptualization of “the veil” as expressed by DuBois, has been a visual metaphor for the representation of race within my work for several decades; particularly in the two projects known as, Schools for the Colored and Red Summer. The newspaper, in its role as public record, commentary, and historic archive, is a veil of information through which most of the country as well as many in the international community, understood and misunderstood these events.

The juxtaposition of newsprint text in Red Summer is such a strong element. Upon viewing your wider portfolio I noticed that several of your projects take on multimedia approaches. What draws you to the pairing of imagery with the written word?

I began making images in the late 1980’s of a small, historically African American community in southern New Jersey known as Whitesboro. The photographs started as a traditional documentary project. However, as I continued to make photographs it became clear that I was often participating in long conversations about the history of the community. At the time I was not thinking about using the narratives in my work but nonetheless I started recording and taking notes so that I would have references to use as descriptions of the people and the setting.

Shortly after making photographs in Whitesboro, I was told about a small cemetery of African American Civil War veterans, in what was now an all-white community. Photographing the cemetery led to research at the National Archive to retrieve their veteran’s folders. It became clear to me that the images and the narratives needed to be connected directly within the artworks. This led to the pairing of the image with the narrative texts to tell the invisible histories of the sites. Throughout the “Small Towns, Black Lives” project (1989-2002), I combined images with text and used archival materials to tell the stories of the communities.

In the “Red Summer” project, I returned to the use of text and archival materials combined with the photograph as a means of accessing the visible and invisible narratives of the sites. I am drawn to the remarkable ways that text and image interact and create new and complex representations of time and place.

The reported events included in this work took place specifically between 1917 and 1923. How did these years in particular become of interest? Do you feel that the connection between this period and the contemporary US is especially poignant? If so why?

The project began and remains primarily concerned with the 1919 Red Summer (as named by James Weldon Johnson). My work started in 2011 while working on an artist residency at Bemis Center in Omaha, NE. The story of the lynching of Will Brown is a powerful story in Omaha and within the landscape of the city. Anyone can stand at the location where he was lynched or at the intersection where a crowd gathered to be photographed around his burned and dismembered body. It was clear that many thousands of people were passing through these spaces everyday unaware of the historic erasure of that event.

This experience led to the longer-term goal of photographing what had become known as Red Summer and the sites that were involved throughout the U.S. Throughout the country, Black communities were being attacked and ultimately hundreds and maybe thousands (there is a lack of accounting for the dead in many of these events) of African American were killed.

Gradually it was necessary to broaden the timeframe beyond 1919, to account for the more complex and interconnected events that occurred between WWI and the early 1920’s. I selected 1923 as the end point with the complete destruction of the Rosewood community in Florida. Rosewood was a symbol of the purpose and objectives during this period of white violence against black communities. The violence was not merely a form of intimidation, it was an attempt to drive Black communities from many areas, such as Rosewood.

In the case of Will Brown, if we accept the narrative of his supposed crime (and there is ample evidence to indicate that the charges were untrue), the punishment was not only extra-legal, but also disproportionate to the claimed offence. This is an ongoing thread in the narrative of American justice with regard to people of color. Black men and women have been historically over-criminalized in the perceptions of many Americans. Even when the claims of criminality or non-compliance (crime statistics indicate no actual difference in crime rates between Black and white populations) are true, the use of summary executions (of unarmed or fleeing individuals), on the spot without due process, is the inherited and ongoing injustice. Throughout the many decades of violence used to terrorize black populations in the U.S., there are very few cases of punishment for the perpetrators.

Lead us through the process of creating this work. Over what timeline were these photos created and how did you go about collecting the articles?

The first three Red Summer locations (Omaha, NE; Longwood, TX and Elaine, AR) were photographed during the summer of 2011 during and after the Bemis Center Residency. After these initial images I made very few new photographs until 2016 when I spent several months travelling around the country in a series of car trips, making the bulk of the images for the project. Since 2016, I have added a few additional sites (Wilmington, DE; Chester, PA; Philadelphia, PA; and New London, CT).

Using the same research methods I established in the “Small Towns, Black Lives” projects, I began searching and reading as much as I could about the events of the time. I was already aware of some of the more well-known events, so I had a starting point and there were already several very helpful texts that listed the sites. Unlike the research for Small Towns, where it was necessary to travel to DC for all of the materials, there were many online sources for early newspapers such as the archive at the Library of Congress. In some cases, I received help from local librarians that provided copies of newspapers in their collections, these were mostly helpful in guiding me to a specific location for these events.

In many of these works I am only providing a fragment of the headline and the story. I am often as interested in the stories surrounding the narrative of the so-called riots for the context and for framing the moment. The work has been presented in more than one format, the most common has been with the newspaper image intruding into the frame of the contemporary photograph. However, they also appear apart on the same page in some presentations.

How did you arrive at photography? Were there other creative mediums that influenced your way of working?

I began making photographs as a high school student in Montclair, NJ. From that moment, I have been primarily concerned with camera-based images in various forms. My work has included camera manipulations, computer-based transformations of images, small amounts of video, and lots of direct camera representations of my engagement with race, culture and society.

I am an enthusiastic consumer of artmaking in every medium (visual, performing, and written word) but if I were to single out particular mediums that have influenced my work, it would be painting and filmmaking.

In your statement you reference writer and sociologist W.E.B Dubois’ conceptualization of “the veil”. What influence has Dubois had on your work?

His writings along with the work of other scholars (Black and white) have regularly helped me to shape my ideas about the world and therefore by extension, the photographs I create to make sense of that world. The concept of the veil was especially significant while I was working on the project “Schools for the Colored.” In one of the opening chapters of “The Souls of Black Folks,” Dubois tell the story of a childhood experience with discrimination during a holiday event at school. Ironically, he attended an integrated school but that did not keep one particular student from making it clear that he was not to receive the same acknowledgement as the other white students. This moment made it clear to him that he was in their world but he was not part of their world. That expression of the veil was the central inspiration for the use of a “visual veil” in my work that effectively screened the structures from the surrounding landscapes.

Aside from your own artistic practice you have an extensive history with teaching as well. How has educating others informed your personal pursuits within photography?

Working in an academic setting has been and continues to be a central aspect of my work as an artist. I am challenged on a daily basis by the students to respond in a meaningful way toward their efforts at artistic production. Their efforts and my replies are a constant reminder of the challenges and rewards of making new work. Even the least effective students provide opportunities for me to help them find ways to succeed as well as articulating the importance of creative effort.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Lauri Gaffin: Moving Still: A Cinematic Life Frame-by-FrameDecember 4th, 2025

-

Dani Tranchesi: Ordinary MiraclesNovember 30th, 2025

-

Art of Documentary Photography: Elliot RossOctober 30th, 2025

-

The Art of Documentary Photography: Carol GuzyOctober 29th, 2025