Stephen Crowley: Time Spent: Florida 1972-1984

I discovered Stephen Crowley’s terrific exploration of Florida in the 1970’s and 80’s when jurying Photolucida’s Critical Mass Competition. Stephen’s project, Time Spent: Florida 1972-1984 went on to be selected as one of the Top 50 portfolios of 2015. At the young age of 20, Stephen had already identified himself as a street photographer and had a rare ability to capture moments that, now seen 40 years later, were insightful, telling, and iconic. His work allows us to consider a period in history that comes after the shape-shifting era of change in the 1960’s and early 1970’s and realize that Florida was slower to evolve and that the stark contrast between the classes was ever present.

Stephen Crowley began his career as a photographer in 1972 during a stint at a community newspaper in Jupiter, Florida. Mr. Crowley moved to Washington DC in 1986 where he covered the remaining two years of the Reagan presidency and the Iran-Contra hearings on Capitol Hill for The Washington Times. In 1992, Crowley moved to The New York Times Washington bureau to cover The White House and Congress, and he was embedded in the Dole, Bush, Kerry, McCain, and Romney campaigns. In his personal work Crowley searches for morsels of humanity, irony and humor, collecting images of the country’s character as hinted by physical structures, shifting light patterns and happenstance.

On Feb. 5, 2002, Crowley, a graduate of the photography program at Daytona State College, was cited as “Photographer of the Year” by the White House News Photographers’ Association for a portfolio that included his essays “Voices of Afghanistan” and “A Day in the Life of President Bush.” In 2001, Mr. Crowley was part of a team at the New York Times that won the Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, “How Race is Lived in America.”

In 2002, the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography was awarded to Crowley and four other photographers at The New York Times for work produced during the war in Afghanistan. That same year he received an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degrees from the Corcoran College of Art + Design in Washington, D.C. In 2005, American Photo Magazine included Crowley on its list of the 100 Most Important People in Photography.

His personal photography has been exhibited in shows at the Library of Congress, The National Geographic Society, and the Corcoran Art Museum.

TIME SPENT: Florida 1972-1984

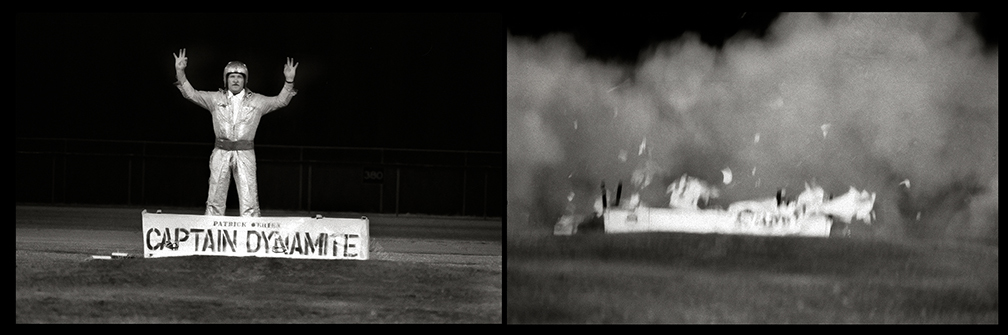

When the 60’s ended on January 27, 1973, the day the U.S. Selective Service announced there would no longer be a military draft; I was a 20-year-old fledgling street photographer. Forty years later I re-examine my work heralding the start of this most curious and seldom documented period of American history: 1973-1984.

The cultural hegemony had claimed an apparent victory: the threat of nuclear war had lessened; the U.S. had won the space race to the moon; women’s rights and racial justice had been addressed; and US military prisoners held in North Vietnam started to trickle home.

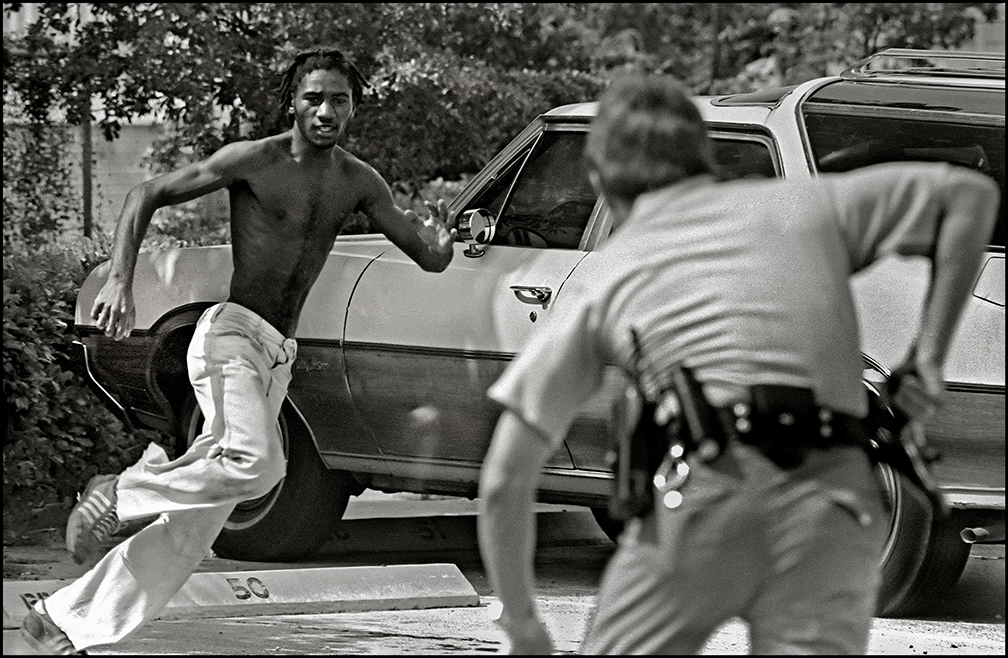

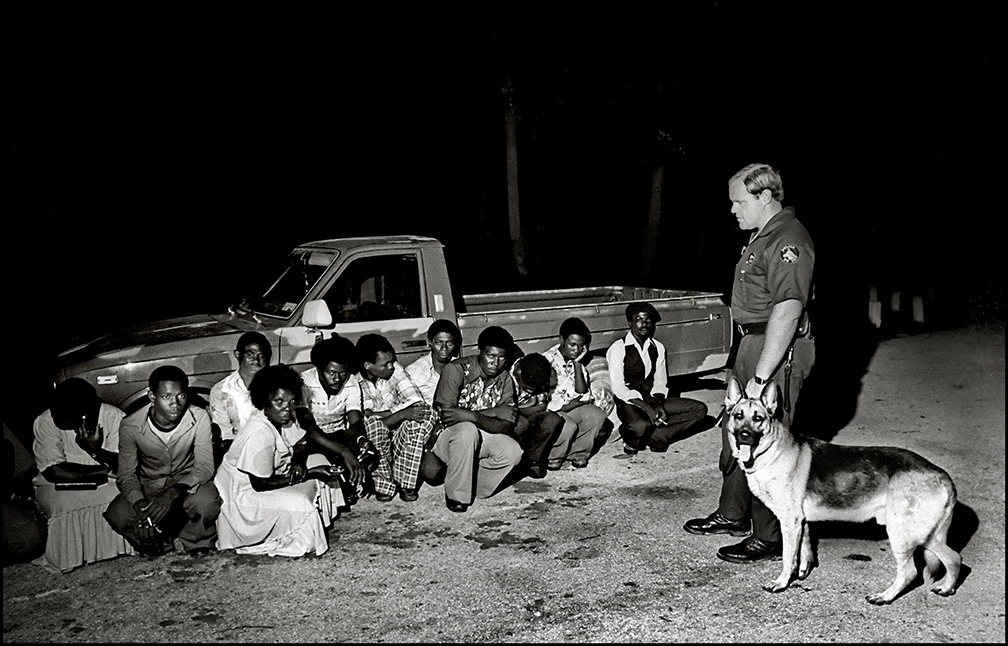

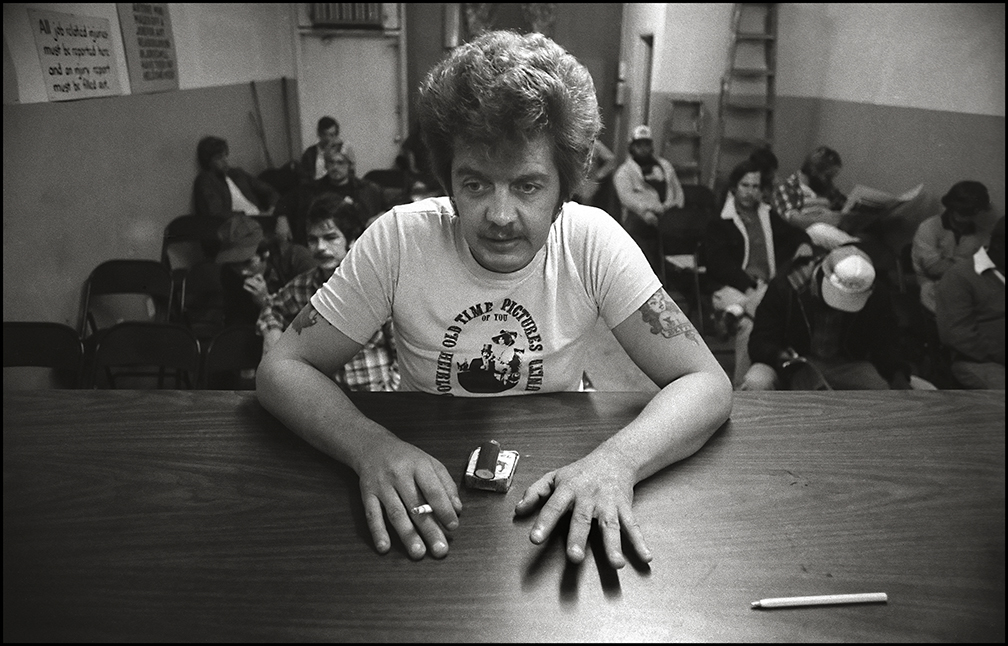

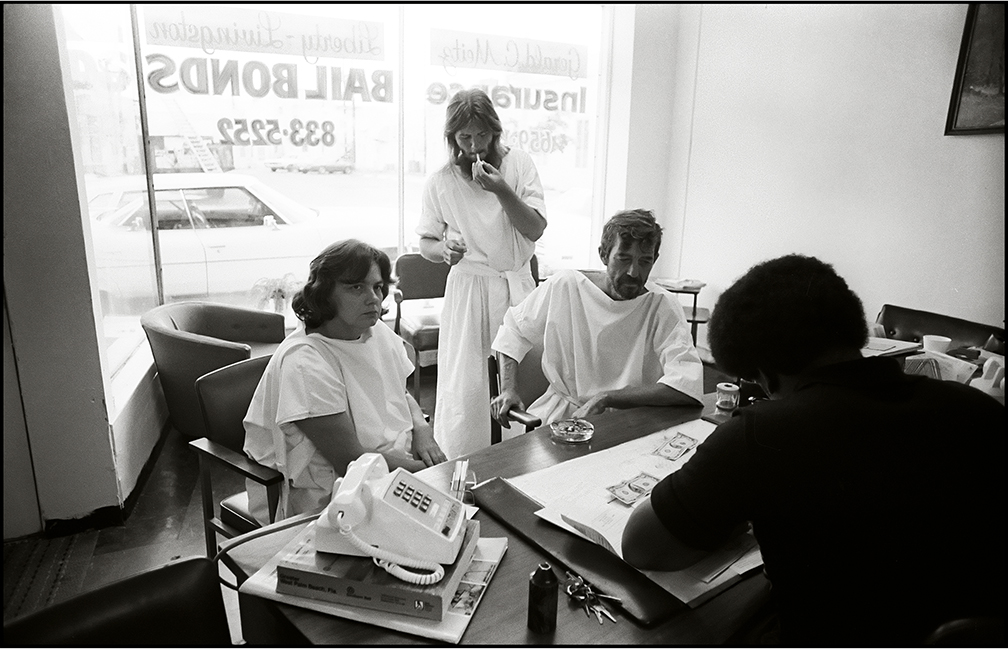

Yet beyond these victories a deeper look revealed: latchkey children struggling in homes with two working parents; the domestic economy overwhelmed by oil shortages and double-digit inflation added insult to a profound recession, which further heightened the growing disparity between the classes.

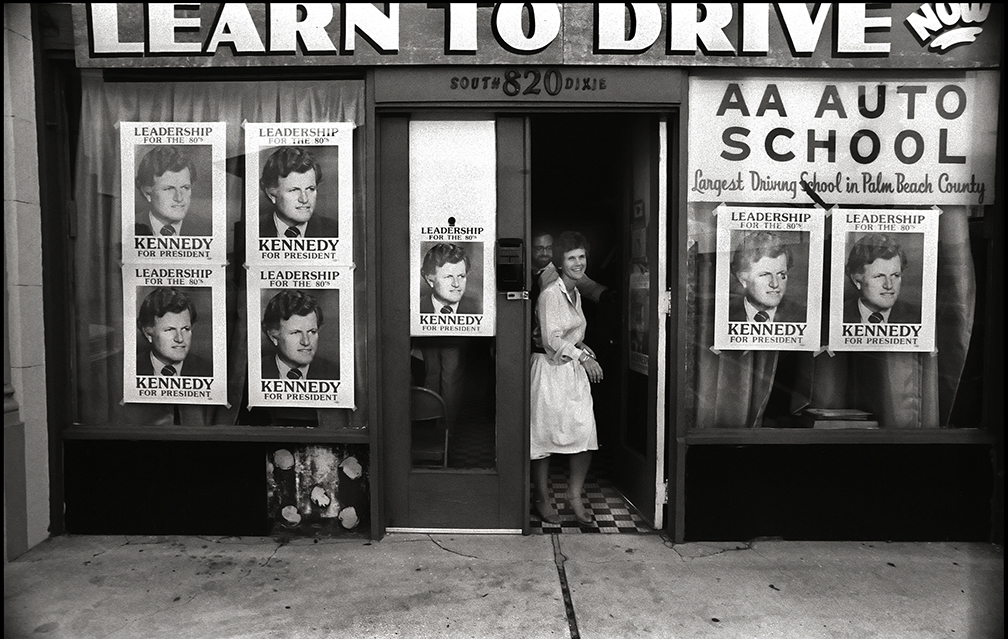

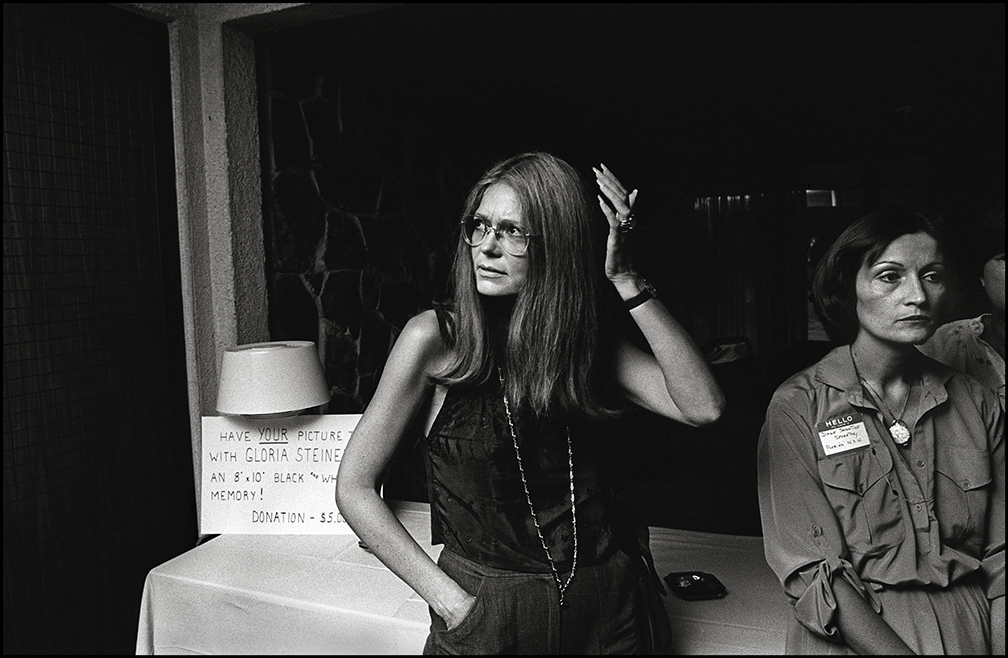

I began to photograph the cultural, educated and political elites who touched down briefly during “the season” to host parties and fundraisers at their mansions on the islands and peninsulas along the coast and the baby boomers as they slipped into the easy no-account life of relativism, enjoying their newly won loosening of restraint and discipline.

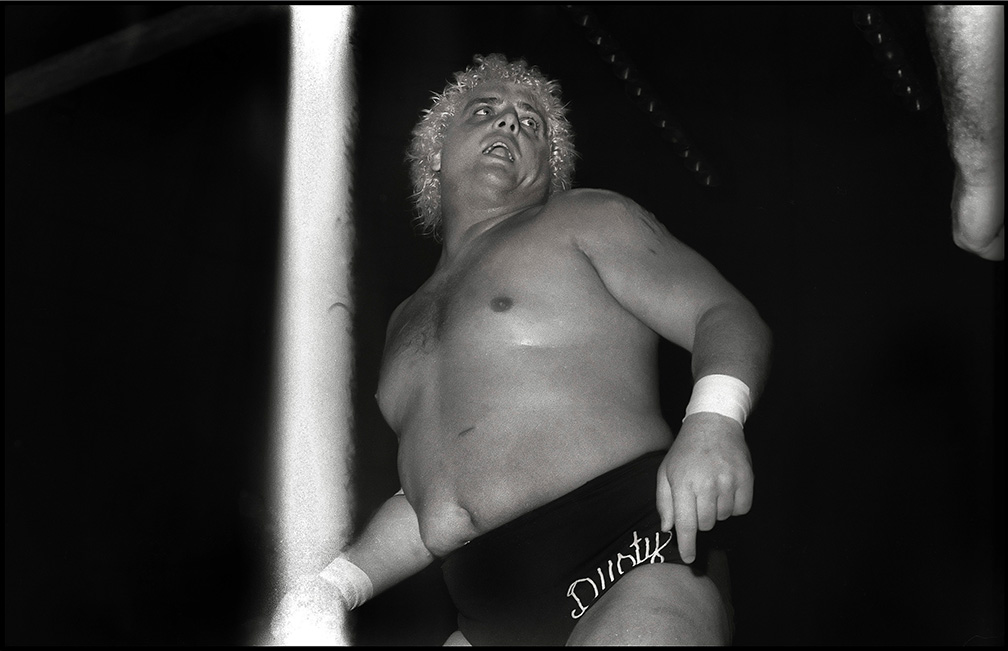

If opportunity was no longer a reliable draw, the weather was enough to attract Guatemalan refugees escaping civil war; homeless drifters or the mysterious tribe of “Jesus People” and the “greatest” generation, raised during the great depression and steeled during a world war, who retreated behind the gates of closed retirement communities.

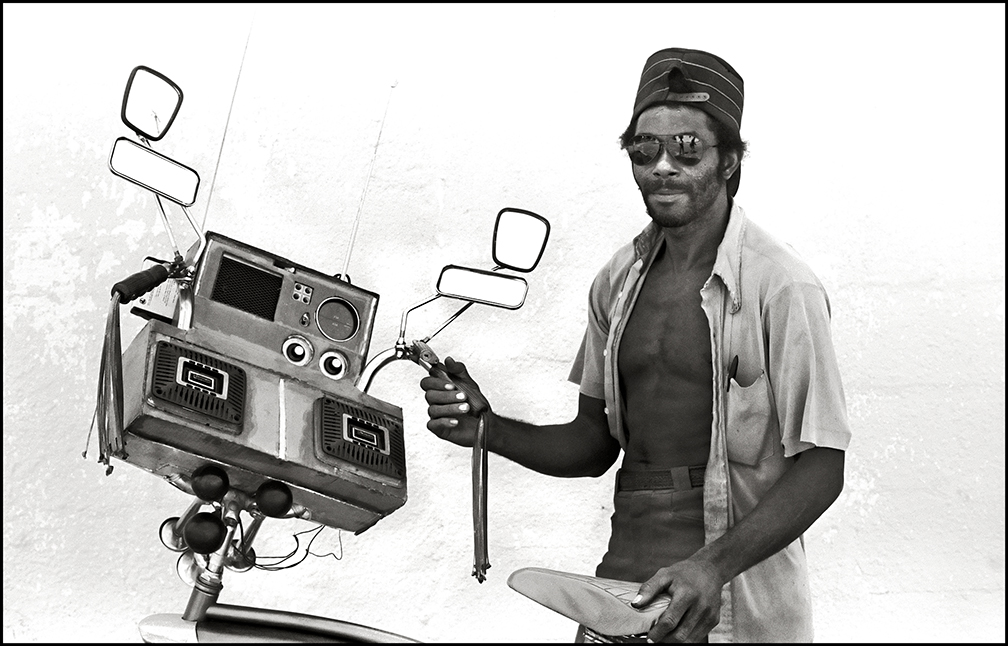

Non-conformity was the new conformity. Protest music gave way to a fledgling punk scene, largely overshadowed by the disco era, which was eclipsed by the “urban cowboy “ movement.

A more informed look, decades hence, at these early negatives reveal more clearly the dichotomy of rich and poor, opportunity and lack, political promises made and broken.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Greg Constantine: 7 Doors: An American GulagJanuary 17th, 2026

-

Yorgos Efthymiadis: The James and Audrey Foster Prize 2025 WinnerJanuary 2nd, 2026

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Celebrating 20 Years of Critical Mass: Cathy Cone (2023) and Takeisha Jefferson (2024)October 1st, 2025

![In the early morning of Sunday, September 15, 1963, four members of the United Klans of AmericaÑThomas Edwin Blanton Jr.,Herman Frank Cash, Robert Edward Chambliss, and Bobby Frank CherryÑplanted a minimum of 15 sticks of dynamite with a time delay under the steps of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, close to the basement.

At approximately 10:22 a.m., an anonymous man phoned the 16th Street Baptist Church. The call was answered by the acting Sunday School secretary: a 14-year-old girl named Carolyn Maull. To Maull, the anonymous caller simply said the words, "Three minutes", before terminating the call. Less than one minute later, the bomb exploded as five children were present within the basement assembly, changing into their choir robes in preparation for a sermon entitled "A Love That Forgives". According to one survivor, the explosion shook the entire building and propelled the girls' bodies through the air "like rag dolls".

The explosion blew a hole measuring seven feet in diameter in the church's rear wall, and a crater five feet wide and two feet deep in the ladies' basement lounge, destroying the rear steps to the church and blowing one passing motorist out of his car. Several other cars parked near the site of the blast were destroyed, and windows of properties located more than two blocks from the church were also damaged. All but one of the church's stained-glass windows were destroyed in the explosion. The sole stained-glass window largely undamaged in the explosion depicted Christ leading a group of young children.

Hundreds of individuals, some of them lightly wounded, converged on the church to search the debris for survivors as police erected barricades around the church and several outraged men scuffled with police. An estimated 2,000 black people, many of them hysterical, converged on the scene in the hours following the explosion as the church's pastor, the Reverend John Cross Jr., attempted to placate the crowd by loudly reciting the 23rd Psalm through a bullhorn. One individual who converged on the scene to help search for survivors, Charles Vann, later recollected that he had observed a solitary white man whom he recognized as Robert Edward Chambliss (a known member of the Ku Klux Klan) standing alone and motionless at a barricade. According to Vann's later testimony, Chambliss was standing "looking down toward the church, like a firebug watching his fire".

Four girls, Addie Mae Collins (age 14, born April 18, 1949), Carol Denise McNair (age 11, born November 17, 1951), Carole Robertson (age 14, born April 24, 1949), and Cynthia Wesley (age 14, born April 30, 1949), were killed in the attack. The explosion was so intense that one of the girls' bodies was decapitated and so badly mutilated in the explosion that her body could only be identified through her clothing and a ring, whereas another victim had been killed by a piece of mortar embedded in her skull. The then-pastor of the church, the Reverend John Cross, would recollect in 2001 that the girls' bodies were found "stacked on top of each other, clung together". All four girls were pronounced dead on arrival at the Hillman Emergency Clinic.

More than 20 additional people were injured in the explosion, one of whom was Addie Mae's younger sister, 12-year-old Sarah Collins, who had 21 pieces of glass embedded in her face and was blinded in one eye. In her later recollections of the bombing, Collins would recall that in the moments immediately before the explosion, she had observed her sister, Addie, tying her dress sash.[33] Another sister of Addie Mae Collins, 16-year-old Junie Collins, would later recall that shortly before the explosion, she had been sitting in the basement of the church reading the Bible and had observed Addie Mae Collins tying the dress sash of Carol Denise McNair before she had herself returned upstairs to the ground floor of the church.](http://lenscratch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/001-16th-Street-Baptist-Church-Easter-v2-14x14-150x150.jpg)