Photographers on Photographers: Daniel George on Millee TIbbs

For the entire month of August, photographers will be interviewing photographers–image makers who have inspired them, who they are curious about, whose work has impacted them in some way. I am so grateful to all the participants for their efforts, talents, and time. -Aline Smithson

When I was in graduate school (that has to be the best way to lose people’s attention when starting a sentence), I came across a series of self-portraits in which the photographer was nowhere visible. She was hiding behind a rock, inside an oven, or at the bottom of a lake. The titles of the images were simple, and further imbued the work with what I interpreted to be a dry sense of humor (i.e. “Self-Portrait Kneeling Behind and Altar to the Virgin Mary”). I liked them and they remained catalogued in my mind—occasionally becoming part of conversations on self-portraiture in class with my students. Almost ten-years later at a conference for the Society for Photographic Education (another attention losing sentence starter), I was introduced to this person—Millee Tibbs. I do not remember the specifics of our initial conversation, only that it was enjoyable and lasted long enough to miss at least one presentation I had planned on attending. I suppose that’s an indicator of a good chat. I chose to interview Millee because I find her photographs alluring, both in cleverness and aesthetic. They have personality, and that says something positive about their maker. Daniel George is an artist whose work explores the interconnection of place and culture as it relates to communal and personal identity. His recent photographs that document gun culture in a rural Idaho community have been exhibited nationally, including solo exhibitions at The Speer Gallery (PA) and The Art Museum of Eastern Idaho (ID). In 2018, his series Trigger Trash was selected as a winner of the Communication Arts annual photography competition. Daniel is currently based out of Vineyard, UT, where he teaches at nearby Brigham Young University.

Daniel George is an artist whose work explores the interconnection of place and culture as it relates to communal and personal identity. His recent photographs that document gun culture in a rural Idaho community have been exhibited nationally, including solo exhibitions at The Speer Gallery (PA) and The Art Museum of Eastern Idaho (ID). In 2018, his series Trigger Trash was selected as a winner of the Communication Arts annual photography competition. Daniel is currently based out of Vineyard, UT, where he teaches at nearby Brigham Young University.

Millee Tibbs’ work derives from her interest in photography’s ubiquity and the tension between its truth-value and inherent manipulation of reality. Tibbs is an associate professor of photography at Wayne State University. She holds an MFA in Photography from the Rhode Island School of Design. She was the 2017 Evelyn Stefansson Nef Fellowship recipient at the MacDowell Colony, and has received multiple national and international artist residencies awards. Her work has been published by Aperture and exhibited internationally, most recently at Pingyao International Photography Festival, China, and at the George Eastman Museum, NY.

Daniel George: Tell me a little about yourself.

Millee Tibbs: I grew up in Huntsville, AL, first near a beautiful state park in the Appalachian foot hills, then on a horse farm, then a block away from the first house near the park. I was unicorn crazy (!) for the first five years of my life, then, much to the consternation of parents, I realized that horses were real, and was horse crazy (!) for the next ten years. I was as tenacious as my parents were accommodating, hence the horse farm. Never having felt comfortable with conservative Southern politics or the religious fanaticism of the South, I chose a college as far away from the South (geographically and philosophically) as I could get. Unfortunately, Vassar proved to be as ideologically dogmatic, just with a different politics. I studied Studio Art because I thought that I always knew I wanted to be an artist (but recently realized that was probably a seed planted by my kindergarten through 12th grade art teacher, Mrs. Costes), and Hispanic Studies, because I really wanted to study abroad. When I graduated I was awarded a travel grant that afforded me the opportunity to go to the Hispanic Caribbean to “travel and see art.” What I thought would be a six-month trip ended up a close to seven-year sojourn in the Dominican Republic before I decided to go to grad school and seriously pursue a career in the arts. I attended RISD and studied photography. Four years later I accepted a full-time position at Wayne State University in Detroit, MI, where I was recently tenured.

DG: So, the interest in unicorns stems from your youth. I was wondering about the roots of your Virgin Land, Wyoming series. I hope you have a secret archive of unicorn drawings that are completely saturated with glitter glue. When did photography become your medium of choice? Was it always a focus throughout your Studio Art studies?

MT: If only! My drawing phase came after I shifted my obsession to horses. No glitter glue, though.

I came to photography in college, but outside of the Studio Art program. At the time, Vassar didn’t offer classes in photography. My work-study was at the slide library*. The assistant curator became a good friend and mentor. She taught me about equivalent exposures, the joys of fiber paper, and how make a “snappy” print. There was also a photo club that a friend coerced me into joining freshman year. She and I made cringe-worthy photographs of each other in flowy, Victorian dresses at Vassar farm, then spent all night printing them in the darkroom. I quickly became addicted to the glow of the safe light and the smell of fixer. By the end of my undergraduate education, I had (thankfully) passed through the on-location faux fashion shoot phase and used photography for both of my theses in Studio Art and Hispanic Studies concentrations.

In addition to the magic and alchemy of photography, which is something that I am revisiting in my work now, what drew me to it over other media is its subtractive nature. Photography starts with everything, then through a process of elimination the vastness of the world is edited down to a single frame that occurs at a fraction of a second. A blank sheet of paper is much more intimidating to me. That said, I’ve never been interested in straight photography either. I am much more attracted to playing in the space between representation and mediation.

*A slide library was a visual resource archive that housed thousands of 35mm film transparencies of artworks that were projected during art history lecture classes. It also provided a study room for those same classes that featured black and white photographic prints reproduced from art books.

DG: Yeah, I find it interesting that your work varies in proximity to the straight photography aesthetic–all the while maintaining a high degree of intervention. What would you say have been the driving influences for you to continue to work this way?

MT: I think of art making as puzzle solving. The puzzle that I keep returning to is how, inside the framework of the photographic, can I make an image that undermines or questions photographic truth? Photography’s truth value is its most salient (and dangerous) characteristic. Left unexamined and at its worst, it can perpetuate and normalize stereotype, sentimentalize history, and aestheticize suffering. I want to draw attention to photography as something that acts on us as a mediated representation of the world, and in the case of vernacular photography, encourage us to perform for it.

As a maker, I enjoy tactile interaction with the photograph. After working digitally for many years, I felt something was missing from my practice. Working physically with the photograph as an object allows for the unexpected in a way that editing in the computer (or at least the way I was editing in the computer) didn’t.

DG: What have you been up to lately? If Instagram is to serve as a record of your goings on, it looks like you’ve been adventuring in the Himalayas. Were you there to make work, or was that a leisure trip? Although, leisure is probably the incorrect word to describe hiking in those mountains.

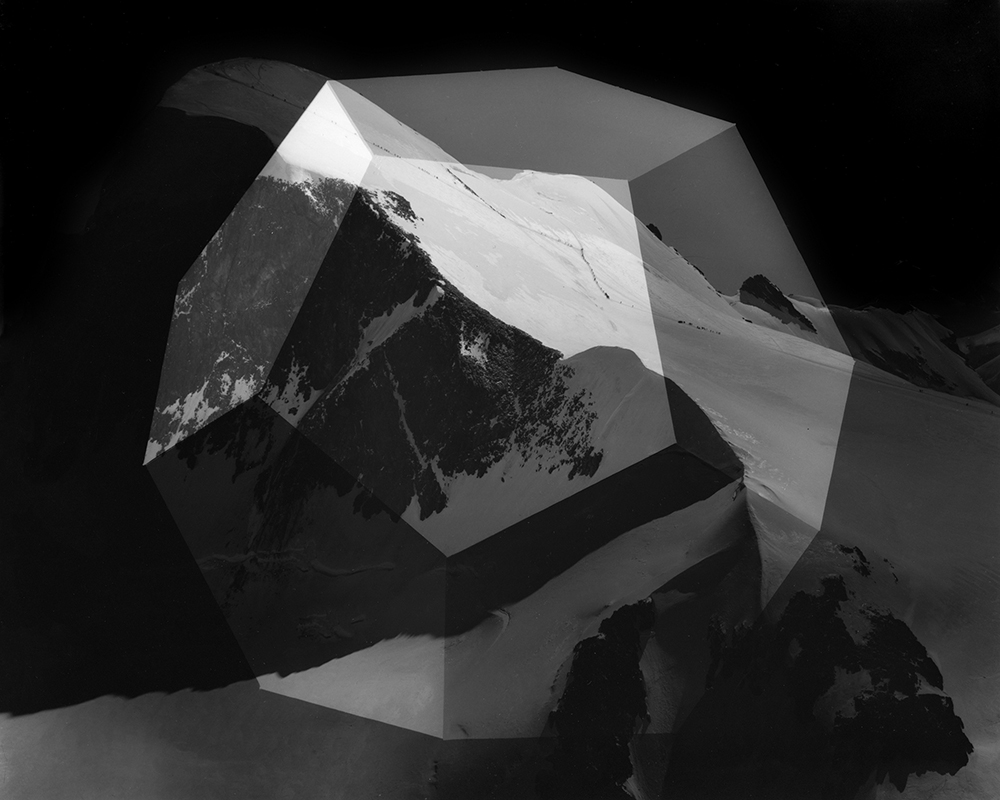

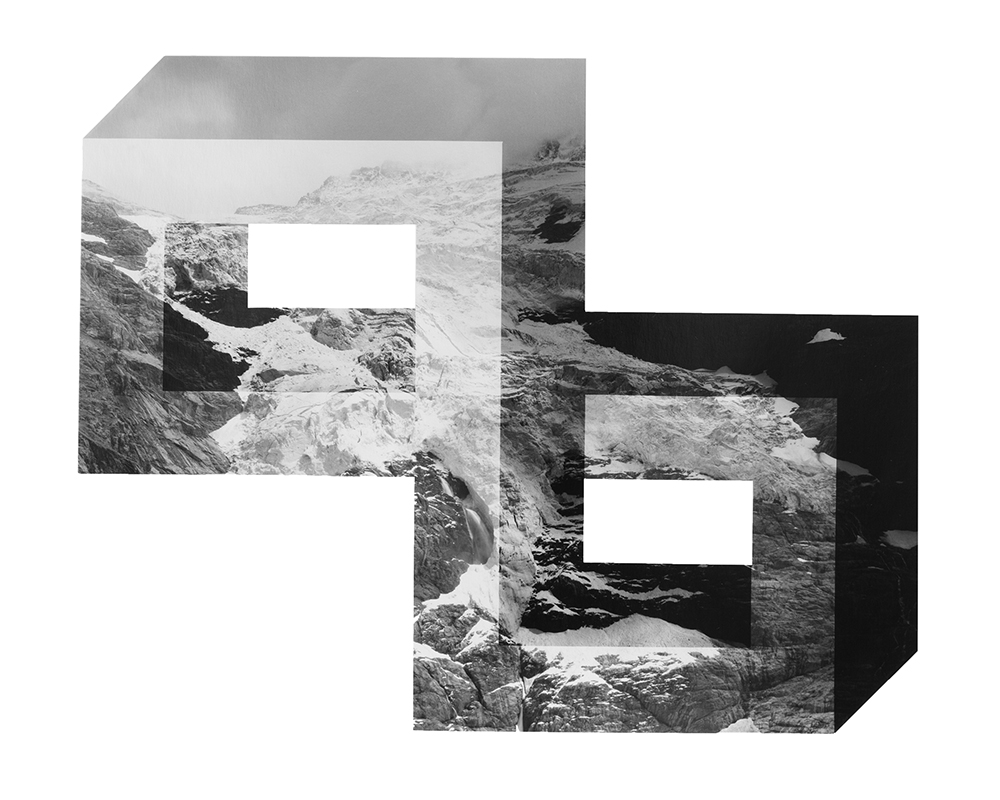

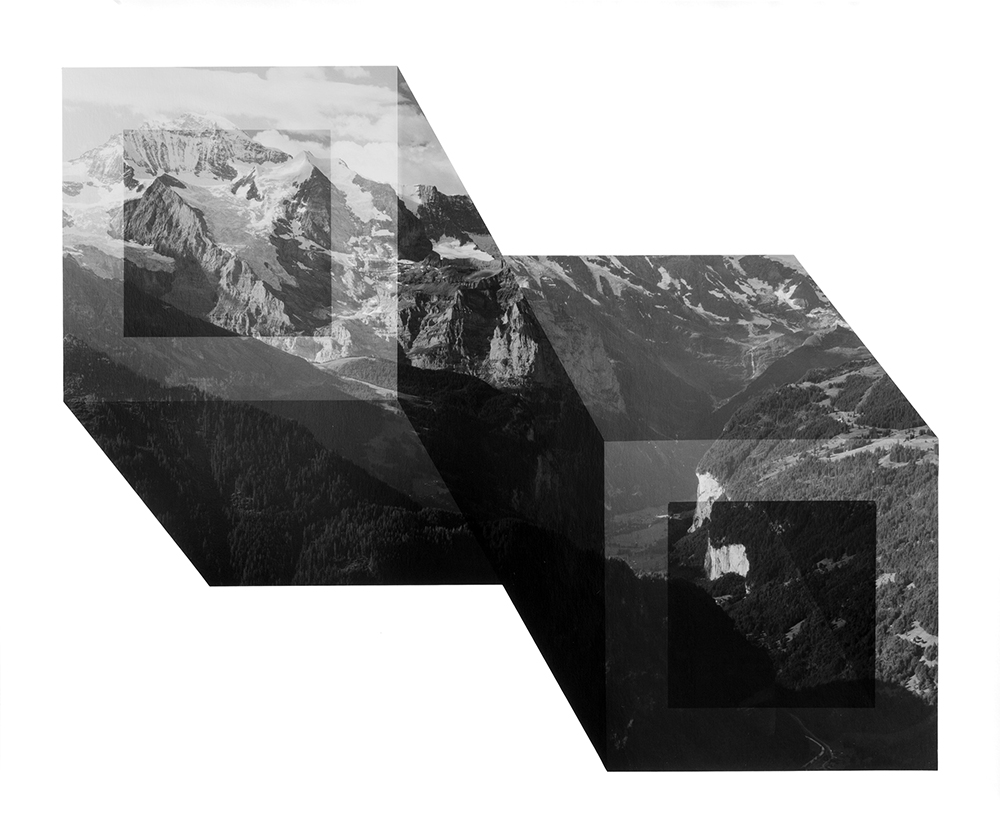

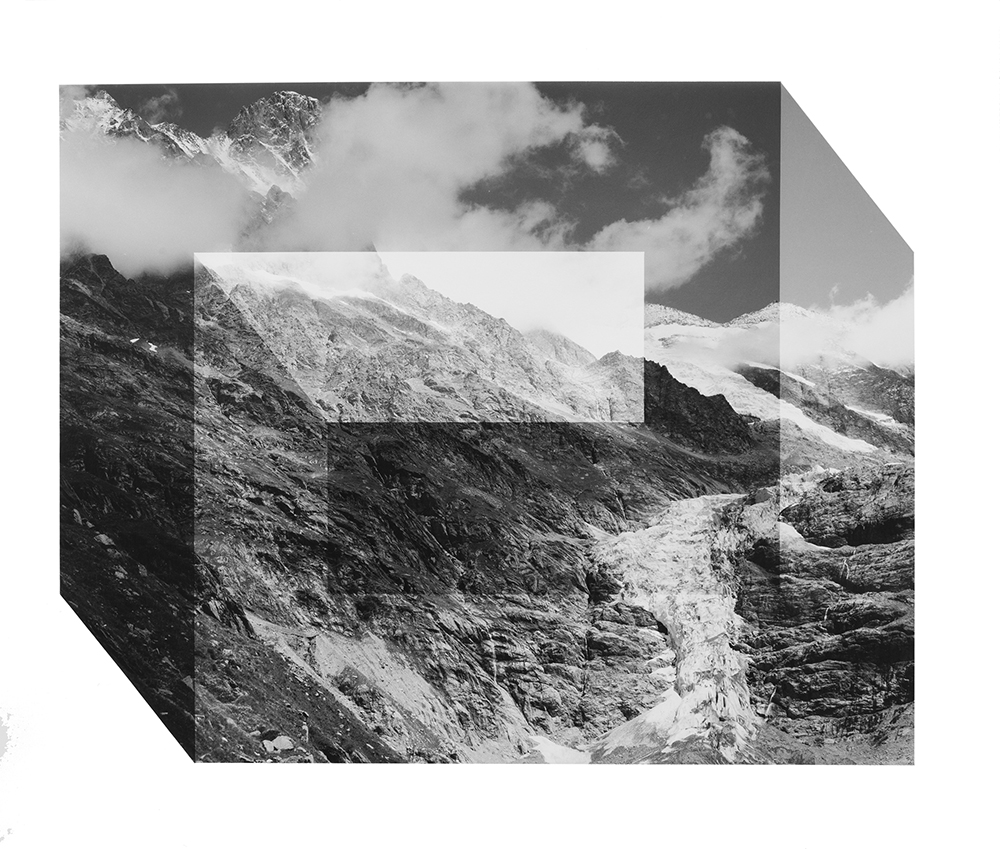

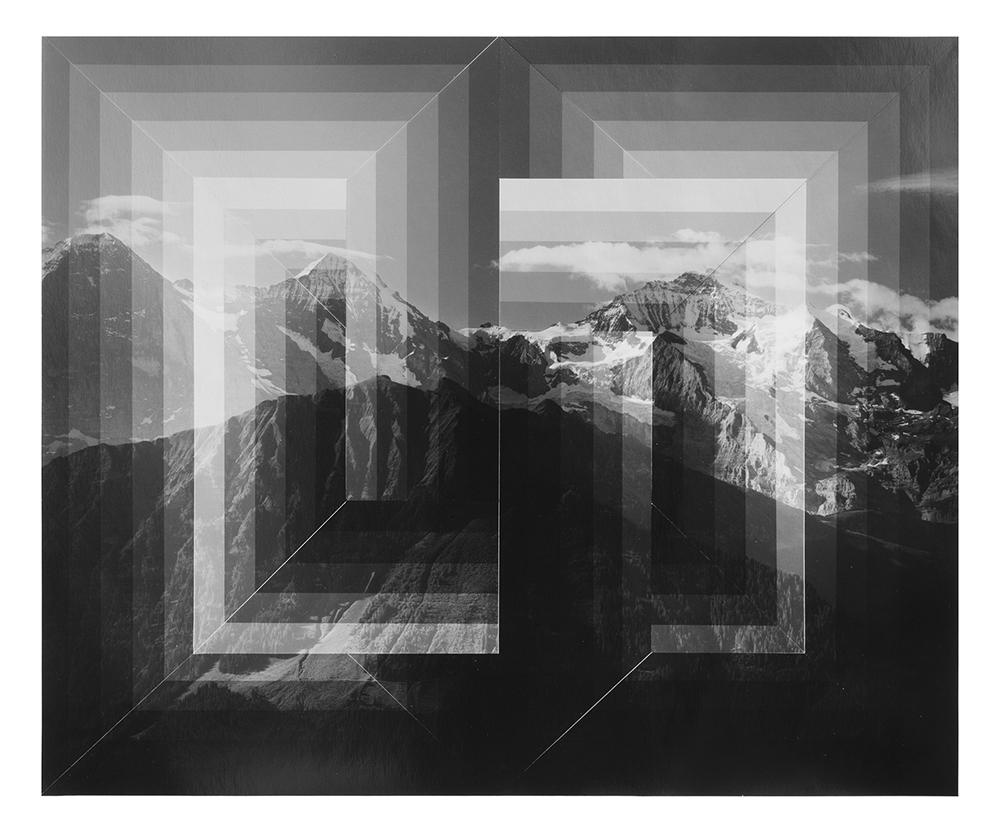

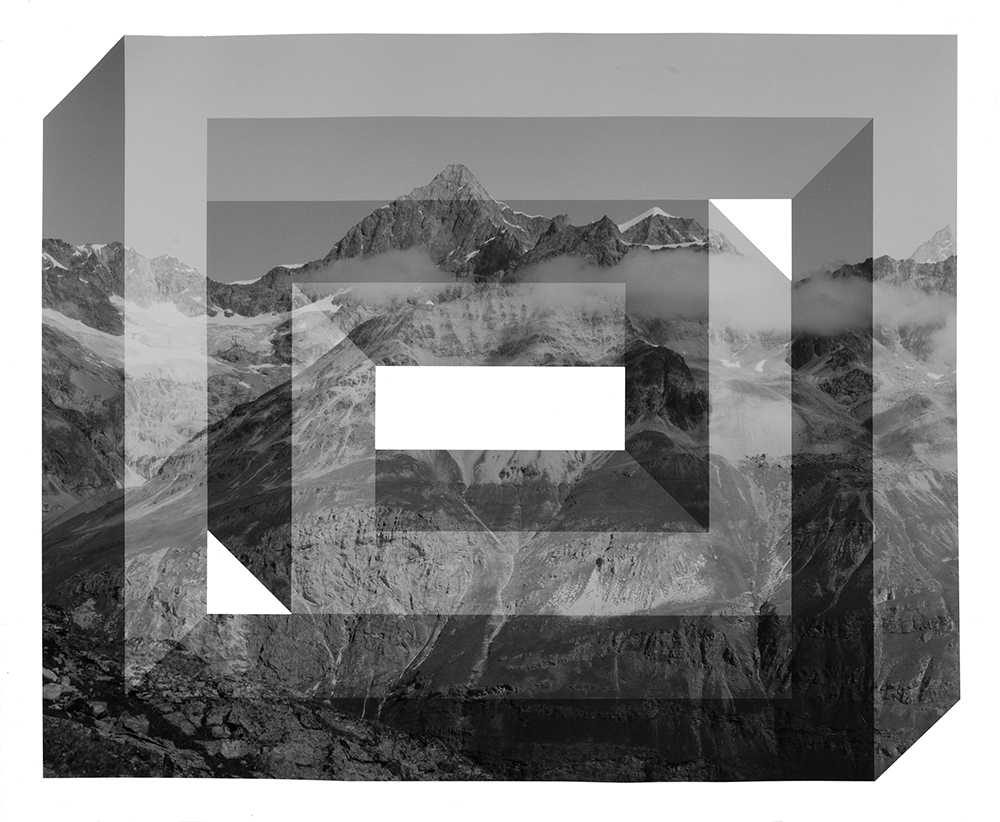

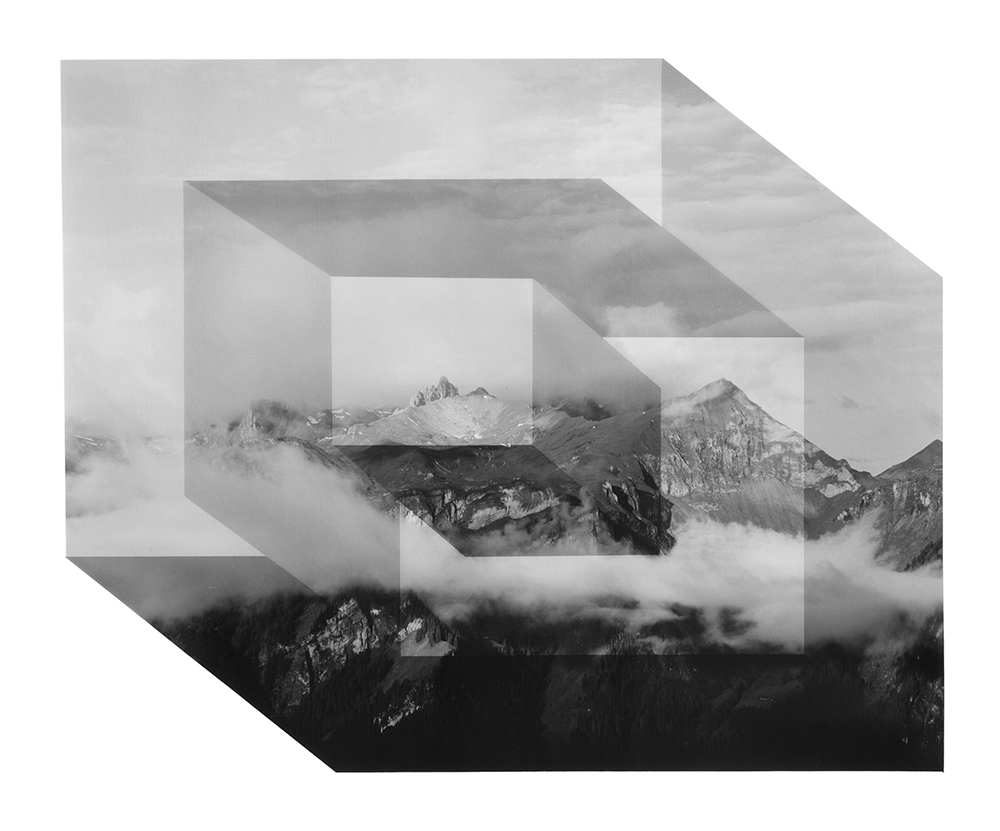

MT: Yes! I was at an artist residency in Nepal for two weeks, then spent another four weeks trekking and photographing, mostly in the Everest region. The trip was for a project that I’ve been working on for the last couple of years titled “Mount Analogue.” As I was working on my previous body of work “Mountains + Valleys,” I became increasingly interested in the relationship between photography and the sublime in the context of landscape representation. Where “Mountains + Valleys” dealt specifically with iconic American landscapes, “Mount Analogue” uses the mountain as a symbol to explore the paradoxical relationship between photography, which can only represent what is in front of the camera’s lens, and the sublime, which exceeds the limits of perception.

A huge part of my process has been embodying the mythic labor of landscape photography by hiking classic trekking routes with my 4×5 camera to photograph iconic vistas. The first phase of the work uses imagery from the French and Swiss Alps. I hiked from Chamonix, France to Zermatt, Switzerland, then a year later I hiked around the Jungfrau region of Switzerland. In Nepal, I hiked to the base of Mount Everest (Sagarmatha). Despite having been x-rayed at least a dozen times in transit, and having broken my ground glass pretty early on in the trip, my film seems to have come out OK… (one of many magical occurrences on that trip).

DG: Wow. You must have some great insights into the do’s and don’ts of long-distance hiking, large-format photography. I won’t ask you any questions regarding that stuff because I like the idea of other people suffering through trial and error. It’s character building. However, I would like you to talk about your interest in the landscape as a subject. A lot of people gravitate toward that genre, so I am interested in your personal motivation. And at what prompted your manipulations to straight images of the landscape?

MT: I’m glad you used the word “genre.” It suggests a history of form that I am really interested in. My earlier work investigated the codes and conventions of vernacular photography – personal archives of snapshots in particular. What attracted me to those images was how incredibly generic they are while simultaneously evoking specifically personal nostalgia.

My focus shifted to landscape after my first artist residency experience. I spent a summer at the Santa Fe Art Institute and found that all I wanted to do was to hike the mountains of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. Out of guilt, I brought my camera along, but soon I couldn’t stop myself from taking really saccharine photographs of the western landscape, which produced more guilt. I sat with the photographs for about a year. I was hired at Wayne State University and moved to Detroit during that time. In my new, urban environment, I longed for the landscape that those images held. I realized that my nostalgia for the West was bigger than my individual experience, but was part of a larger, very complicated American metaphor.

The transition from a concept-forward practice using mostly self-portraiture to a materially-based process was messy. I was trying to fit a new subject matter into an old way of working. Bad art was made. I finally got to a point where I hated the work I was making so I started paying attention to the art that I enjoyed viewing. Letha Wilson’s photo-sculptures were an epiphany to me. They were smart and beautiful. I remembered that before grad school and my obsession with photographic theory I had been working with photographs as objects – stitching onto them and covering things with them. I went back to a much earlier way of working but with a new criticality.

DG: You have mentioned a couple of your residency experiences (New Mexico, Nepal), and your website lists about a dozen others in which you have participated throughout the years. So, it seems like you spend quite a bit of time making work outside of Michigan. Do you feel it is necessary to travel in order to realize your creative vision? I recognize that the upper Midwest has little to offer in terms of mountains, so not much help for Mount Analogue. Do you make work locally, or do you prefer the road?

MT: I like to travel. A lot. I especially like to travel with a purpose. Photography is a special medium in that it grants us access to the things we photograph. If we chose to photograph things we love, then we get to access those things. I would like to work more locally. It seems like that would be a better and more sustainable long-term practice, but for now I am happy to go away for a month or two every year and experience new places. Then I get revisit them in my studio the rest of the time. Residencies have been particularly nourishing to my practice. I’ve met so many wonderful artists who have become really good friends. Having that concentrated time to make has also been really productive.

DG: How do these experiences inform your role as an educator?

MT: I try to teach to my interests as an artist. It keeps me excited about teaching, and my research for the classroom helps inform the work I make. I’d like to think that I can enlarge the world view of my students by sharing my experiences with them, or at the very least plant a few seeds of curiosity.

DG: Not only are you very active in making work, but in exhibiting and publishing as well. You are also the recipient of numerous grants and awards. How do you stay on top of all that? It certainly requires effective time-management strategies. What are some of your best practices for getting your projects funded and your work shown?

MT: Thanks. I never feel like I do stay on top of that. Deadlines slip through my fingers pretty regularly, and the rejection letters…sigh. Back in the day when institutions sent out paper rejection letters, I threw a Whine and Cheese and Wine party with my artists friends. We made our rejection letters in to party hats and cut them into paper dolls, snowflakes, and confetti. Sadly, the internet has ruined that.

Because of my academic schedule, I find it easier to make work in the summer and administrate in the school year. I am in awe of my colleagues who are able to maintain their creative practice all year long. Once the school year starts, mine is pretty much over (sad face emoticon.) But, let’s talk about what I do well… Organization is key. I have an elaborate architecture of folders inside folders organized by date and subject for upcoming opportunities and I mark really important deadlines on my google calendar as well. I also color code ones that require recommendations. In the early days after grad school I spent a lot of time on the internet researching opportunities. Thankfully, sites like (ahem) Lenscratch has made it a lot easier for young artists to find these. Many of my shows, etc. have resulted from friendships with other artists. The funding has primarily come from my University. Tier 1 research universities are pretty much the Medici’s of modern America.

DG: Whine Cheese and Wine sounds amazing. We’ll have to put our heads together to come up with an equivalent for email rejections. I’m always interested in hearing about how other artists manage their productivity–especially those with teaching responsibilities. There are many discouraging moments in artist’s lives that force them to reconsider what they are doing and why they are doing it. What keeps you making?

MT: I have a strong creative drive. If I’m not making art, then I’m experimenting in the kitchen or writing music. When I made the decision to be a visual artist, I committed to building a life that would support my creative practice. I have been remarkably fortunate to have succeeded at that. On good days, making is joyful and fulfilling. Then there are days when I would really much rather be a mechanic. Seriously. But I can’t ever imagine not wanting to creatively problem solve and make things. There are certain questions that I try not to ask myself because they lead down a deep, dark rabbit hole of despair. Unfortunately, these are usually the ones on grant applications. I try (try!) to keep a sense of humor when things feel grim, and most importantly, I have an amazing community of artists friends both here in Detroit and across the world that remind me that making is just what we do, there is no other option.

DG: Finally, there is a tradition to end Lenscratch interviews by asking the interviewee to describe their perfect day. Since we are looking at your Mount Analogue work and the labor of hiking is part of your process, I would like to modify the request slightly by asking you to describe your perfect day as if on one of your many hikes.

MT: Ah, that’s a nice question. I wake up early after a restful night’s sleep to pre-dawn darkness and position myself in front of whatever peak I slept nearest to. Fog fills the valley, but the skies are clear. With pre-loaded film holders in hand – prepared the day before in preparation for my perfect day – I set up my camera so that I capture the morning light raking across the side of the mountain as the sun rises. Maybe a stray dog greets me and introduces me to his pack. Then I go back to the lodge, eat a hearty breakfast of warm muesli and coffee, reload my film holders, and set off for my next destination. The temperature is cool and the air is dry. The first big ascent comes early in the day, and while the sun is still low in the sky, I reach the pass that presents a spectacular vista of the range. There are clouds in the distance. I stop to take more photos, reload my film holders, and eat some chocolate. For the rest of the day I am hiking above the tree line – no steep descents, only an undulating path that hugs a glacial moraine. There are more animal encounters, but of the cloven hooved variety. I arrive at a mountain hut by late-afternoon. I settle in and have a post-hike beer (apparently I’m at a low enough altitude to not preclude imbibing alcohol.) As the sun gets lower in the sky, I set up my camera at the base of a peak and wait for the drama of sunset. I return to the warmth of the wood burning stove in the hut and dine with fellow trekkers and mountaineers. I am fast asleep after catching a glimpse of a star filled sky and am soon dreaming of snowfall. The end.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026