Gina Costa & Janet Sternburg explore memory, objects, & the Los Angeles Fires

TWO PHOTOGRAPHERS QUESTIONING

Gina Costa & Janet Sternburg explore memory, objects, & the Los Angeles Fires

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico

Janet Sternberg: I’m at my home in San Miguel talking with award-winning photographer Gina Costa. I met Gina when she was visiting here last year. She and I quickly became friends, connecting with a deep understanding of one another. Both of us are compelled by the past and how it presses on our work.

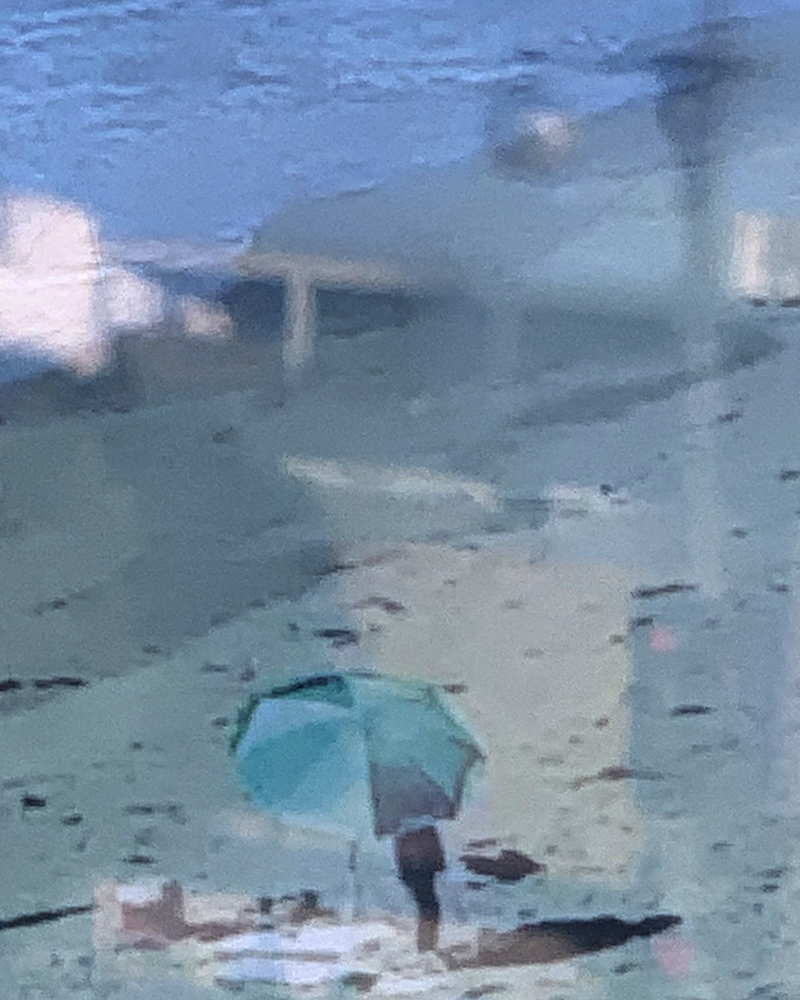

Now, a year later, she has returned to Mexico. We’re sitting in my living room across from an old stone wall on which I’ve hung some of my photographs from my first ones in 1998 to the present. I began here in San Miguel with a disposable camera which was all that was available then. Its limitations — no depth of field, automatic focus — showed me a different way of seeing that became a vision of interpenetrating and layered time and space.

I’ve had the great honor of Wim Wenders writing the introduction to my first monograph. He said, “This book about the nature of photography is intense and confusing, but definitely essential.” I hadn’t set out to baffle, but t I am deeply interested in revealing how the mind works without boundaries.

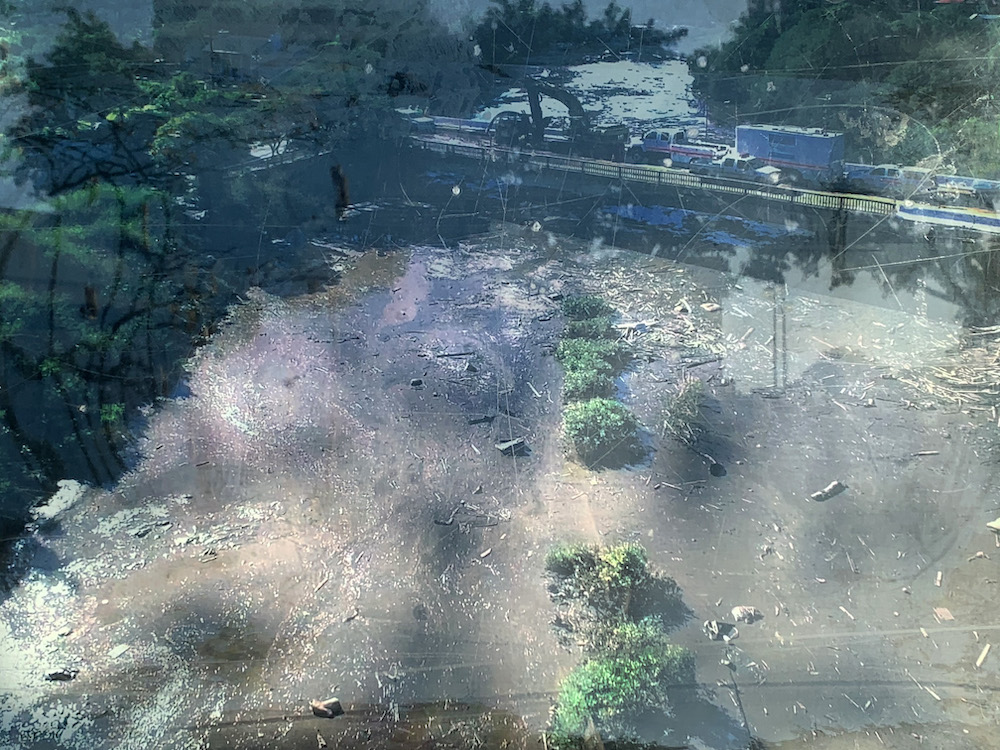

Gina Costa: Hello, I’m Gina Costa . I’m an art historian, museum curator, and photographic artist and it’s the 22nd of January 2025. And the sun is shining. I’m in this beautiful room with a woman who is such an inspiration, talking about some of the things that are most important to me. My photographs are a meditation on memory. I’m asking to what extent are one’s personal narratives informed by memories. How do we construct memories from the past in order to give meaning to the present?

I’m especially interested in how quotidian objects are tied to memory, I have a great friend, Gene Halton who has influenced me on this subject. He’s a professor at the University of Notre Dame who with coauthor, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, has written a seminal book The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self. Gene will walk into your house and tell you what every object says about you, how every object has significance. Today we’re talking about the loss of these objects — photographs, archives, mementos –along with the loss of self in the recent Los Angeles fires.

JS: We’re asking questions that aren’t new but have become so much more immediate now with the losses of Los Angeles fires. Why are objects so important to us? What of value resides in the object itself, or lives instead in one’s memory of it? What happens when the object is gone? And why do we save our mementoes? What will they mean to future generations? Where does all this richness go after we’re no longer here? The objects, the cherishing?

GC: When a fire takes your personal narratives, you have to resort to memory to reconstruct all of that. And it can be overwhelming because we feel at a loss, because memory is very capricious. Scientific study reveals that every time we remember something, we actually remember the last time we remembered it. Therefore, we are continually constructing memory. Each and every time we remember who gave us that vase or that photograph, we’ve reconstructed it again, the memory of the event and the person. We live with all these constructions that are strung together like a necklace that becomes our identity, our personal narratives.

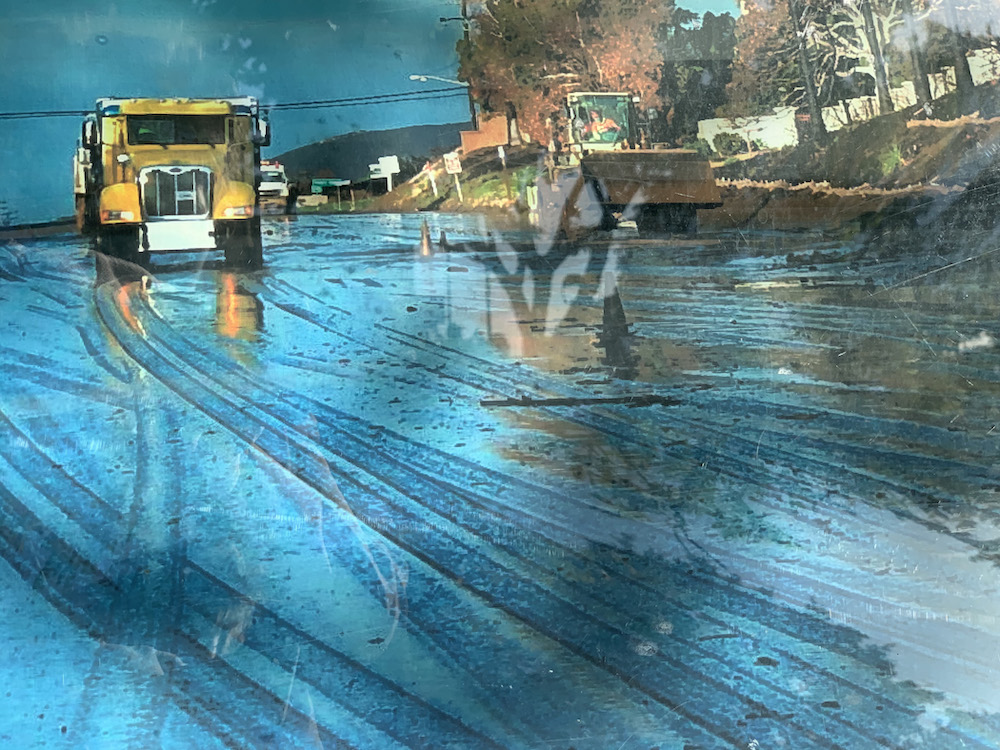

All the people who have lost things in the Los Angeles fires have suddenly lost those memory theaters, those supports, the armature for who they are, not knowing what they’re going to do tomorrow, where they will be, what they can piece together to reconstruct all the things that are essential to their sense of self and identity.

JS: I’ve had a love affair with objects for much of my life, and in many of the same ways that you are talking about. Years ago I encountered a line that has great meaning for me. It was written about the sort of poet who uses language but since you and I are also visual poets, it’s for us too. “Poets are people who speak for things that cannot speak.”

I love the idea that as artists we can be conduits for mute objects. When I take a photograph, it’s almost as though I can feel the object calling me, wanting to be heard. It’s a romantic idea, I know, but it bears on the moment of taking a photograph, when there’s always a connection between photographer and subject, and here between the inanimate and the animate. I felt this especially during COVID when I walked through Los Angeles streets, at first seeing mostly desolation and then finding traces of human presence.

GC: What about those objects we hold onto against all common sense? I still have a little green dress that I wore all summer in Italy while I was pregnant with my son. I came back to the United States to have my child, but I found that I didn’t want to throw out that dress. It was like a cocoon of nurturing motherhood. And here I am dragging it around thirty-eight years later. Do I need this dress to remember that exquisite summer?

JS: Rilke writes that people keep crutches in their closets long after they’re needed. There are rich psychological meanings in that image but for now I’m going to narrow them down to a sundress I kept in my closet since high school, pink and white with spaghetti straps. At first (‘d wanted to see whether I could fit into it through the years, but I gave up on that. I kept it anyway, thinking of it as a trigger to memory. Could I say goodbye to the dress and still have access to that young woman, her experiences, her emotions?

Eventually I did say goodbye. But l can still conjure its tightness at my waist and the crisp cotton holding up firm breasts, one of which is no longer part of me.

Would a photograph of me wearing that dress be useful for remembering? There was one — I can see it, in my parents’ driveway. But neither dress nor mage would get to the heart of things. I think that as we get older, and I am much older than you, — how old are you — ?

GC: I’m almost 68.

JS: I just turned 82. I think that as we get older we need to place more trust in our associative powers, live more intimately with our neurological and psychological powers that allow us to link the past with now in ways that are more complex than memory alone.

This past summer, I was at a hotel in the Mexican countryside where the owners were hosting their grown children and grand-children, among them a grandson who came with three friends, all materializing on the terrace wearing white cotton t-shirts, the apparel of teenage years. So too a memory materialized of my high school boyfriend, the smell of his spearmint gum, the feeling of his shoulder blades under that white cotton. I would have loved to touch these young men standing in front of me.

I realize I’m in well-worn Proustian territory. But my point is that these feelings and evocations aren’t only memories. There’s a line I’ve written in my book, Phantom Limb: “Memory is diasporic, traveling from person to person becoming story.”

Do you think we may be enshrining memory at the expense of opening to assemblages of past and present?

GC: I’m walking around with questions. One of the projects that I’m working through now deals with photos and stories of my family. Why do I need to do this? It’s a preoccupation that relates to my family, especially my grandmother Gina Costa, who survived the brutalities of WWII in Italy. I have heard so many horrible stories of her incredible courage and strength under unspeakable conditions that I cannot share here. My father couldn’t even talk about this time, he was so traumatized. During his life a detail would surface, then be tucked away again.

You know there’s new research on trauma, positing that it’s passed down through generations in our DNA as well as our psyches. I know that I have trauma from my grandmother and my father. It’s not exactly mine. It’s inherited. I’m asking myself whether my photographs are subconscious reflections of these inherited memories? Do I continue to search out subject matter that ties me to them?

JS: I think that photographers are partly investigators, and that to investigate means not to be determined by the past. Our generational ghosts can take us only so far. It’s all so poignant. A friend wrote me recently about “the impossibility to reach out to the past and yet the will to revive a glimpse of it.” The fires took away the reaching and the glimpse. The question becomes how can people find the will to restore? And if not to literally restore, then to find another way? The questions facing so many people in Los Angeles are those of a history shared with others who have had to leave everything behind.

GC: Right now I’m thinking of Kandinsky who wrote a little book in 1912 Concerning the Spiritual, about the spiritual in art-making. It’s the gift I give all my graduating students. He says that he paints because he has to. It’s who he is, he has no other choice.

JS: That’s what we have to search for in the ashes, the ongoing self. Maybe that’s the essential personal narrative. As for us, you and I, we search with. the help of the phoenix of photography.

I’m starving. We’ve been talking nonstop for over an hour and it’s time for lunch. We need to take care of other needs, yes? On offer Is a roast chicken.

GC: I would love that.

Gina Costa is an internationally known fine art photographer, art historian, museum professional, and independent curator. She earned her graduate degrees in art history from the University of Chicago, and has worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, The Art Institute of Chicago, and currently, as Professor at the University of Notre Dame She has written several books and museum catalogues , among them on 20th century Mexican graphics, and Midcentury Modernism in Chicago.

Winner of the 2023, 2019, and 2018 Julia Margaret Cameron Photography Award, and 2023 Critical Mass finalist, PhotoLucida, her work has also been featured in Lensculture, F-Stop Magazine, and Lenscratch. Her work has been shown at the International Center of Photography, New York; The Mira Foundation, Porto Portugal; Griffin Museum of Photography, Winchester MA; Filter Space, Chicago; Perspective Gallery, Evanston, Il; The Rebekka Jacob Gallery, Charleston, South Carolina; the Minneapolis Photography Center, Minneapolis, MN; The Vermont Center for Photography, Battleboro, VT; The LightBox Gallery, Eugene Oregon; Tethys Gallery, Firenze, Italy: and MART, Rovereto, Italy. Her works are in public and private collections in the United States and Europe including The Fratelli Aliniari Archive, Florence Italy.

Janet Sternburg is a fine art photographer, writer of literary books, maker of theatre and film, and an educator. Her solo shows include the Seoul institute of the Arts, Korea; Contrasto Galleria, Milan; two-year traveling exhibition, Berlin to Munich; USC Fisher Museum of Fine Arts, Los Angeles. Her photo publications include Aperture and cover/ portfolio in Art Journal, as well as three monographs from Distanz Verlag: Overspilling World: The Photographs of Janet Sternburg, with essays by Wim Wenders, Cathy Opie (2016); I’ve Been Walking: Los Angeles Photographs (2021) with conversation, Jane Bennett; and Looking at Mexico/Mexico Looks Back, in collaboration with Jose Alberto Romero Romano (2024).

Among her literary publications are The Writer On her Work (“groundbreaking . . landmark,” Poets & Writers cover story); Phantom Limb (“the perfect metaphor,” Bill Moyers); White Matter (“beautiful. . . healing,” Los Angeles Review of Books); Optic Nerve: Photopoem.s (“redefining both poetry and photography,” Molly Peacock, Foreword). She is the recipient of the REDCAT AWARD, (2016), “given to individuals who exemplify the creativity and talent that define and lead the evolution of contemporary culture.”

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025