Focus on Gallerists: Catherine Edelman of Catherine Edelman Gallery

Daniel Beltrá, “The Amazon” Installation View (2020), courtesy of Catherine Edelman Gallery, Chicago.

This week, we’ll be featuring a series of interviews with commercial, fine art gallerists across the United States. Our conversations will address how these particular art dealers—whose galleries and platforms range in age from a handful of months to over thirty years—see their role in the art world, and how they’ve navigated different curveballs (including, but not exclusive to, an ongoing global pandemic) along the way.

At a time when many art world constituents find themselves thinking more deeply and critically about various aspects of our arts institutions—from what work is being exhibited (and what work is not), to who is allowed (or denied) access and upward mobility, to who these organizations ultimately serve (and do not serve)—it is perhaps more important than ever to be in dialogue with the figures at the helm of these initiatives. Operating in between artists, collectors, and the public, commercial gallerists and their galleries walk an interesting—and complicated—path, juggling artist representation, exhibition programming, and community engagement, all while pursuing financial viability.

Today, we begin with a pillar in the contemporary photography world who has long been negotiating these issues: Catherine Edelman of Catherine Edelman Gallery.

Since its founding in 1987, Catherine Edelman Gallery has established itself as one of the leading galleries in the US devoted to the exhibition of prominent living photographers, alongside new & young talent. The gallery showcases a broad range of subject matter, attracting both the seasoned collector and first-time buyer. In May of 2019, CEG moved to a 4400 sq ft space, expanding its program to include artists readings and panel discussions, with a larger exhibition space and dedicated video room, as the gallery seeks to expand the vocabulary of photography. The gallery’s website provides a wealth of information, including artist talks, interviews with art world professionals, and extensive educational material. To date, CEG has hosted 245 public exhibitions, featuring more than 200 artists.

Erica Cheung: Tell me about the inception of your gallery and how it came to be.

Catherine Edelman: I came to Chicago in 1985 to attend the School of the Art Institute for my MFA in photography. I wanted to be a curator, but I had taken five years to get through college because I switched my major, then two years of grad school, and I was a little tired of school. You need a PhD to become a curator, so I thought I’d run a gallery for five years and get my “business feet,” if you will, and then go into museum work, hoping to bypass more schooling. Early on, I met Robert Sobieszek, who was the curator of photography at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), who mentored me those first five years. I used to go to LA all the time and really wanted to work with him. When the job came up to be his assistant, it was perfect timing. I had gone through the stock market crash in ’87, two Gulf Wars and the recession of ’92, and business was just awful. I was eating Rice-a-roni, and really struggling. But Robert told me not to apply—that he wouldn’t hire me, that I should stay with what I was doing… that I would have more autonomy if I could stick it out. And I listened to him.

While I didn’t set out to be in the gallery world, I knew I didn’t want to be a photographer for a living. I knew I was good at business because that’s how my brain works and I knew that I wanted to put together exhibitions. I never use the word “curate” because I have great respect for people who go through the process of becoming curators, and have the degree, so you’ll never hear me say that I “curate.” I edit, and I put together shows, and I get my ya-ya’s out that way.

EC: One of the things that people commonly say about your programming is that it is so diverse. Within this abundance, how do you think about the balance between programming that is socially relevant and reflective of the times that we’re living in versus programming intended for financial viability?

CE: I have another mentor, John Mulvany, who reminds me that at the end of the day, I need to make money. I understand this, but I also cannot do anything just for the sake of money. Never have, never will. I need to maintain my own integrity, because my name is on the door of the gallery. I trust myself to work with and for my artists in the best way that I know how.

I also do not immediately respond to the various crises happening today. When I feel the need to put together an exhibition about an idea, it is definitely reflective, not responsive. I have put together shows about war, shows that deal with inequality, identity, etc.—but it’s not reactive. I think galleries can make an important contribution to social issues once there is perspective, which usually means things need to settle. I hope that at the end of the day, I can balance my passion and make enough money to pay the bills. My job is to elevate the photographers that let me work with them.

EC: I appreciate the sentiment of working with your artists as opposed to trying to get at things from a more consumer-focused standpoint. And I think doing so is tricky, because commercial art galleries stand as middlemen between artists who are sometimes hard to access (especially if they’re of national/international acclaim), and the general public (both collectors and non-collectors alike). Because of this, I’ve seen a sentiment—particularly in my generation—that art galleries function as ‘gatekeepers’ in the art world. How do you feel about your role as the intermediary between artists and the public?

CE: I think it’s kind of simple. Without artists, the galleries have nothing to show. And without a venue, the artists don’t have a place to show. Today, artists are getting very creative. They have their own websites, and some of them are doing quite well on their own. But they often don’t have access to the business side of things unless they’re with a gallery. And once you’re with a gallery, it is a business. Galleries have to be run in a specific way so that we’re still here tomorrow.

In the best of both worlds, artists understand that it’s a collaboration. I absolutely expect honesty and communication with my artists, and if we don’t have that, we generally don’t last very long. I expect my artists to keep working, to promote themselves even though they have a gallery. Just because they have a gallery doesn’t mean they stop working on their own behalf.

Based on what I’m seeing and hearing, the younger generation does not seem as interested in going to galleries as generations prior. They seem to prefer to do things online. Meanwhile the generation that I grew up with comes back to me because I’m very honest. I don’t do a sales pitch because I don’t believe in sales pitches. That’s the part of the art world that has the bad reputation. The philosophy at my gallery is education. You educate people, and then through education, they can make their own decision as to whether or not they want to purchase.

I don’t really love the word ‘gatekeeper,’ but I do understand its usage. We are an avenue to the museums, we’re an avenue to the collector, we’re an avenue to an international audience. There are only so many people we can represent. It doesn’t do an artist any good to be with a gallery that has a hundred artists. They won’t be remembered. So to that extent, are we a ‘gatekeeper’? Perhaps, but it’s completely subjective.

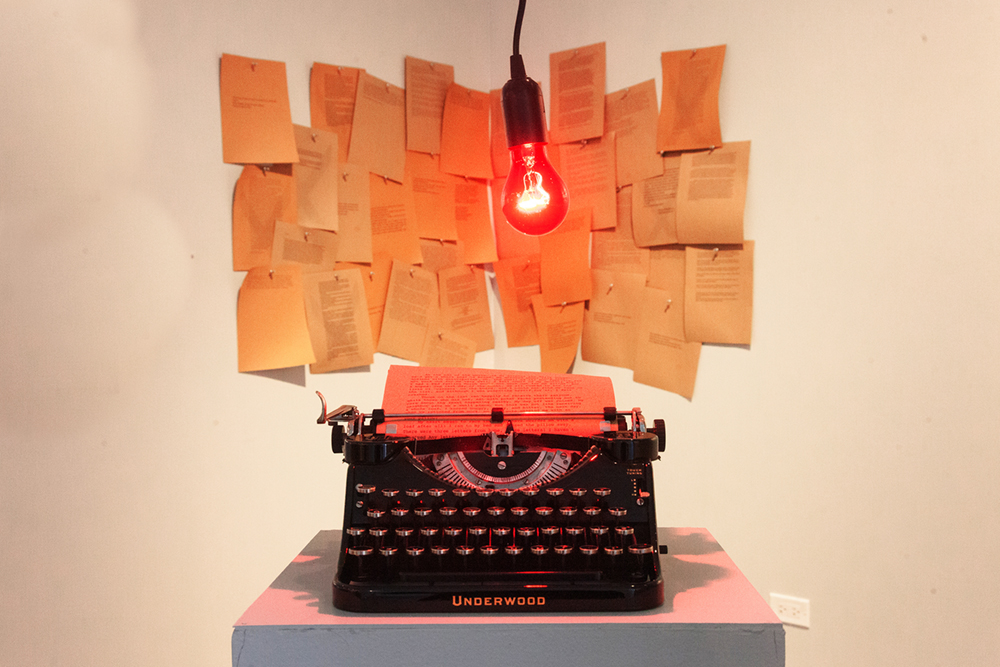

©Marina Black, “Unseen” Installation View, Typewriter Detail (2021), courtesy of Catherine Edelman Gallery.

EC: Scaling out, commercial art galleries exist in a broader art world alongside other organizations like museums, non-profits, and auction houses. I’m curious to know what niche you think dealers and art galleries hold in this ecosystem.

CE: Let’s just talk about living, contemporary artists right now, because otherwise it’s a whole different ballgame. Auction houses exist because artists have gotten acclaim. Most artists’ works are not going to be at an auction unless they already have an established exhibition history, which comes about by going through the gallery system. The galleries, in turn, rely on curators to validate the work, through acquisition or exhibitions, which then raises the profile of the artist.

I love the non-profit world. I just started a non-profit, so I’m a little biased in that regard. But I think non-profit organizations and for-profit galleries can work beautifully together. I’ve always worked with other galleries, non-profits, and museums. I’m not that interested in the auction world because I don’t deal with the secondary market, but I keep up with what’s happening.

Collaboration is key in the art world. You can’t just sit in your gallery and think everyone is coming to you. You’ve got to get out there and make yourself known.

EC: What do you think the future of art galleries looks like—especially given the fact that the pandemic has shown us how brick and mortar spaces are not always sustainable for everybody who owns a gallery?

CE: I firmly believe it’s vital to have an exhibition space if you’re going to represent living artists, because artists want to see their work on the wall. There’s nothing quite like seeing work in person; it’s an undeniably powerful experience, which is why museums exist, and why galleries still have brick and mortar spaces. But if people don’t visit galleries and just experience work online, then it does question the validity of spending the kind of money that we have to spend to have a physical venue.

I am currently trying to reinvent the gallery model, and that is very much due to the pandemic. I don’t have a succinct answer to this; I am in the midst of it. Most of my sales have always been online, and around 90% of my sales have always been out of state. You’ll probably hear the same from dealers in California, dealers in New York… we all say the same thing. It’s the way the art world seems to work, at least among my colleagues. A lot of us are rethinking how to engage with the public in a fulfilling way. I’ve pivoted a few times. I’m older and hopefully wiser.

EC: What are some of the changes that you have made, or are making, to your gallery model as of late?

CE: I had to let my staff go to maintain the gallery, which was the single worst decision I’ve ever had to make. It affected other people who I truly cared for, and who were dedicated to me and the gallery. But I got very, very ill trying to figure it out… in the end, the decision had to be made. When I started in 1987, I worked alone. It’s almost full circle, but now I’m more like a private dealer with a beautiful, spacious gallery. I have a great intern who came my way out of the blue, and art fairs are starting again.

For the last eleven years, my director worked with all new clients. Now I engage with people and it’s very fulfilling. When visitors come into the gallery, they’re the only ones in the space, allowing us to have a dialogue for as long as they want. It’s good for me, and I think it’s great for the public, if they’re interested in what I have to say. It’s funny—it feels almost like the beginning again, but with 33+ years more experience.

EC: Will you tell me about your experience running a non-profit?

CE: I co-founded CASE Art Fund with one of my dearest friends who lives in Norway. The organization’s mission is to raise awareness about children’s human rights through the support and exhibition of photography. You can learn more about what we do on our website.

CASE is unbelievably rewarding because it’s not about specific artists—it’s about a mission, which is very different from the gallery world. I love constantly working on behalf of an idea. I can guilt people into giving us money because it’s about children, and their need for education, regardless of where they live and their circumstances. There are stresses in this part of the art world—you’re constantly trying to raise money, constantly looking for fundraising opportunities. But it’s with a different sense of purpose.

I know that my years in the gallery lead me to this. I know that there’s no way I could’ve started a non-profit without the years of knowledge from the gallery world.

EC: You wear a lot of hats.

CE: I do. I’m a little tired, but not as tired as I used to be. The stress level of owning a gallery has always been very high for me… it’s just my nature. But I only own one hat. I bought it when Anette, my business partner, told me I had to get a hat because we go to Arles every year for the festival and it’s beastly hot. We were passing through Paris, and there was this beautiful hat. It’s really gorgeous. I’ve only worn it once, but it looks great on my dining room chair.

EC: It’s great—I love it.

CE: Thank you, thank you.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Suzanne Theodora White in Conversation with Frazier KingSeptember 10th, 2025

-

Maarten Schilt, co-founder of Schilt Publishing & Gallery (Amsterdam) in conversation with visual artist DM WitmanSeptember 2nd, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025