Justin Levesque: Place/Hold

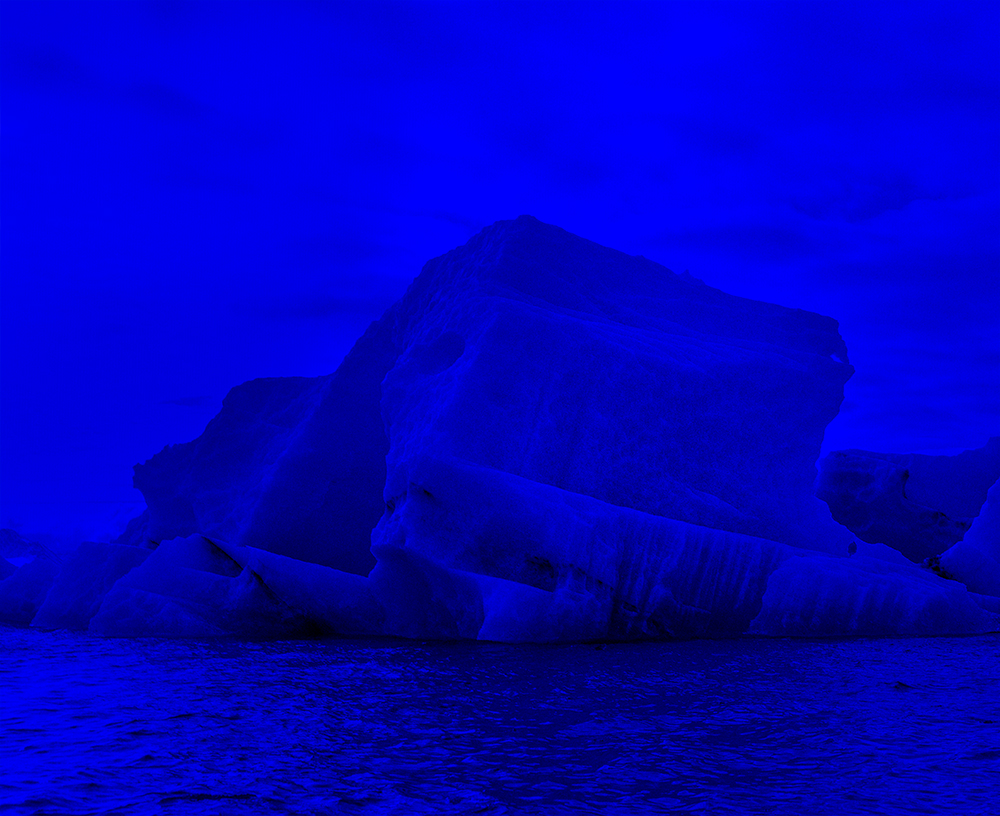

©Justin Levesque, 1 Day at Sea Feels Like 3 Days on Land: 13.03LM 1/3, 13.03LM 2/3, 13.03LM 3/3, archival pigment print with acrylic face mount, 7” x 7″ each, 2017

Justin Levesque is a Portland, Maine based interdisciplinary artist whose work I was introduced to earlier this year. I was initially struck by his work on board a container ship as its something I’ve dreamed of. And his more recent work during an artist residency on a tall ship in the arctic led me to create an interview with Justin. His work is a collection of projects that begins with Iceland, ships, and Maine; a dynamic system of business, culture, history, and humans. Exploring the system revealed more systems.

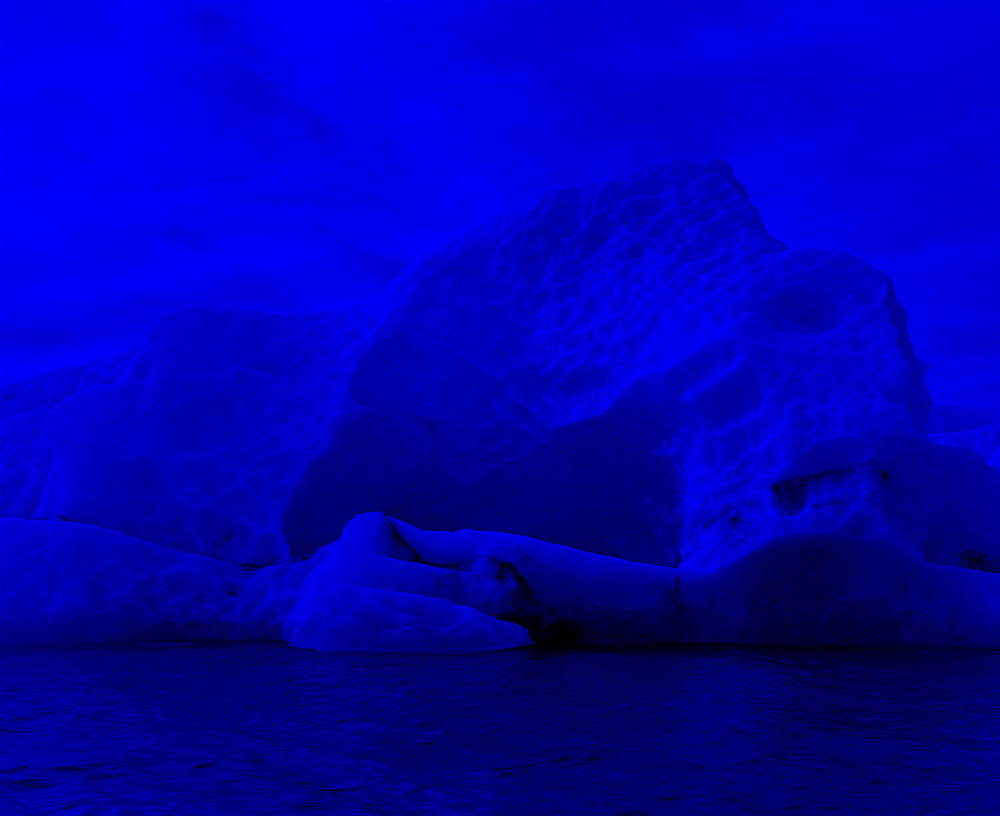

©Justin Levesque, 1 Day at Sea Feels Like 3 Days on Land: 13.02LG 1/3, 13.02LG 2/3, 13.02LG 3/3, archival pigment print with acrylic face mount, 7” x 7″ each, 2017

PLACE / HOLD

PLACE / HOLD is a working title that encompasses several components from a connected network of distinct but related projects that concern Arctic image consumption, data as the new divine, spatial simulacrum, and corporeal complexity.

New works in response to The Arctic Circle are a product of my interdisciplinary practice with a consideration for the materiality and tradition of formal photography and its relationship to new consumer technologies, image-culture, objects in space, and systems. – Justin Levesque

©Justin Levesque, N 79.119464, E 11.851767, archival pigment print from medium format negative with GPS data drawing, 16” x 20″, 2017

©Justin Levesque, N 79.823822, E 12.104159, archival pigment print from medium format negative with GPS data drawing, 16” x 20″, 2017

ED: Greetings Justin. Could you please tell us a little about yourself? Where are you from? Where do you live now? What do you do?

JL: Hey Eliot, I’m an interdisciplinary artist rooted in photography and image-making based in Portland, Maine. Originally, I grew up in the post-industrial city of Biddeford, Maine just 20 minutes south, so, Maine is home, through and through.

Currently, I’m working on several projects related to my participation in The Arctic Circle artist residency in June 2017. When I’m not working on projects related to my creative practice, I have clients I work with on anything from web design to interior design photography to marketing.

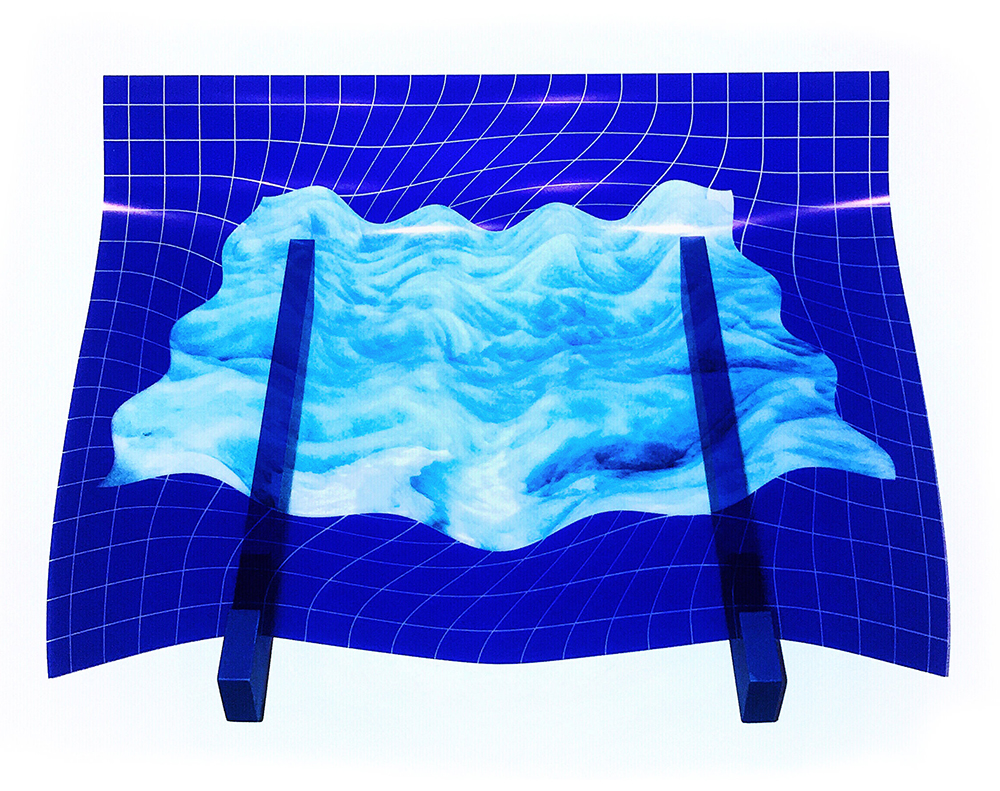

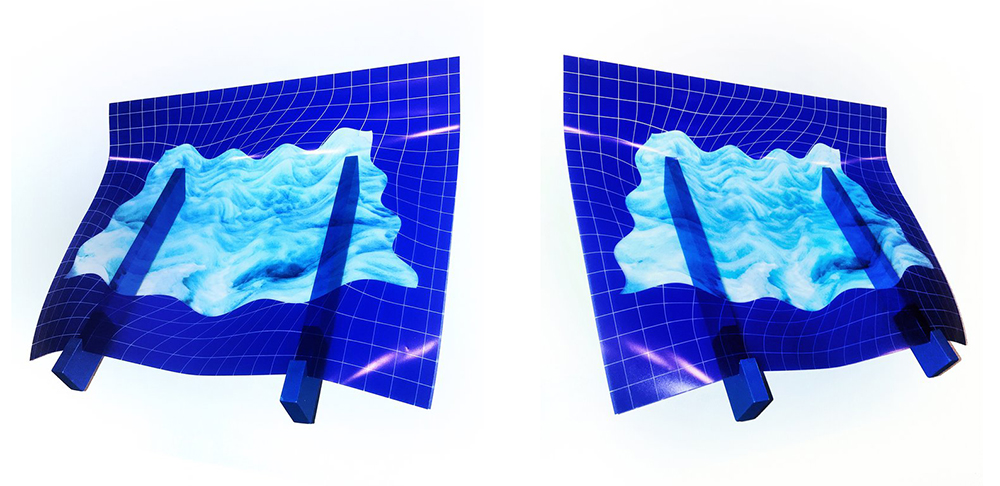

©Justin Levesque, Originally thought to be slippery due to the pressure of an object coming in contact with ice, UV print on transparent film, wood, rubberized paint, spray paint, 24″ x 36″ x 12”, 2018

ED: I’m always interested in hearing how artists go about making a living outside of their artwork. It seems you have some good things going that tie nicely into your art practice. So Maine wasn’t cold enough for you, and you decided you wanted to start exploring the Arctic? What sparked your interest in the Arctic?

JL: The colder the better, in my opinion!

Oddly enough, my interest in the Arctic starts in Maine. In 2013, the Icelandic shipping company, Eimskip, moved their North American headquarters to Portland. Having just returned from Iceland for the first time back in 2014, I was surprised to see the same Eimskip shipping containers in the Port of Portland that I had just seen in Reykjavík. Long story short, I began a project called ICELANDx207 that included an independent artist residency aboard an Eimskip container ship sailing from Maine to Iceland where I made photographs, recorded audio, etc. The result being a related public art exhibition in a shipping container to see into the forces that have so rapidly revitalized the Port of Portland’s commercial potential.

During that project, it was impossible to ignore this larger conversation that was emerging about Maine’s future economic role in the Arctic vís-a-vís shipping. Everyone was, and still is, very excited about this idea; from businesses to universities to city officials and state government. And it’s a serious enough concept that in 2016, The Arctic Council Senior Arctic Officials meeting was held in Portland. It was first time they’ve ever been hosted outside of Alaska.

In many ways, it’s a natural continuation of my previous work to now be looking further north. When I applied to The Arctic Circle residency, the biggest question I was thinking about was: How do we reconcile this potential economic opportunity by way of new shipping lanes with the melting Arctic? I wanted to expand my experience beyond a theoretical idea of the Arctic by actually going there. But since the residency, the questions have completely changed and become less regional, more global, with a focus on the complexity of the system as a whole.

©Justin Levesque, (Detail) Originally thought to be slippery due to the pressure of an object coming in contact with ice, UV print on transparent film, wood, rubberized paint, spray paint, 24″ x 36″ x 12”, 2018

ED: So the entire ICELANDx207 project was completed aboard the cargo ship? That’s pretty interesting. What was it like on the ship? I’ve always been curious about those floating mammoths. Did you ever feel confined in your ability to make work aboard the ship?

JL: Actually, both the ICELANDx207 project and The Arctic Circle residency were on ships. But in the Arctic, it was a much smaller ice-class sailing vessel. There were 30 other participants on the tall ship and sometimes we’d bump into each other’s space but for the most part things have a way of working themselves out when you’re at sea. There’s nowhere else to go, you quickly figure out how to adapt to the environment. In general, my experience has been that ships are psychologically small in size no matter how big they actually are. But I always find that kind of restraint to be beneficial. It forces a creative problem solving process that often makes the work better in the end.

ED: And the 30 participants aboard the tall ship were from all sorts of backgrounds? That must have been fascinating. Your work Place/Hold that you made during this residency seems to grapple with the limits of technology, human perception, and time through things like mapping, virtual reality, and performance. You mentioned a shift in your thinking since your residency, what led you into this shift and these investigations?

JL: Exactly, there were scientists, performers, writers, artists, and even a composer. Collaborations formed across the divide of those categories very quickly. I definitely came out at the end with this incredible new community, many of which are now dear friends.

Prior to arriving in Svalbard, there was certainly this sense of how actually being in the Arctic, in the unique conditions of the residency, was a once in a lifetime opportunity. But instead of allowing that to encapsulate the experience, I uncharacteristically gave myself permission to experiment without explicitly imagining or worrying about the final outcome.

Quelling that anxiety right out of the gate allowed for unexpected discoveries. On one hand, an answer to an idea would form but on the other, new questions were raised.

For example, when I was on the container ship, I wondered: Why does one day at sea feel like three days on land? How could I represent that sense of discordant time in images? In the Arctic, I began to exploit the camera’s capture method on my iPhone to create elongated icebergs, new ice generated by digital error, that are now a series of triptychs. For me, these images speak to that subjective experience of time but they also ask questions about the inherent propensity of the digital image to perform as platitude disguised as action.

I also brought a pretty wide range of gear. A Pentax 67, Mamiya RZ-67, Canon Mark III + three lenses, disposable cameras, iPhone, Garmin inReach Explorer + and a TASCAM Dr-100 MKIII with a shotgun mic. Traveling to Svalbard with it all was heavy and pretty miserable but having those options to respond with was critical.

ED: Were you able to witness the effects of climate change in the Arctic first hand, or did it remain abstract? Climate change is such a huge subject that moves at such speeds that can be difficult for us to perceive with the naked eye and without the aid of scientific data. I’m curious if you were able to actually see the problems we face?

JL: You’re absolutely right, that particular kind of impact is difficult to see in a short period. More than anything, the way I experienced or witnessed the direct effect of climate change was by interviewing our expedition guides. They would often observe differences in the landscape or how the size of a glacier had changed since they first saw it some years back.

But your question does make me think about how there are these quintessential images about the Arctic and climate change; perhaps epitomized by a glacier calving. It’s an extremely linear message that’s conveyed: Look at this mammoth amount of ice breaking off! The Arctic is melting!

Meanwhile, a glaciologist would tell you calving is a natural process that occurs at a glacier’s termination zone. I witnessed several calvings. And while they were all certainly both spectacular, irrevocable, and truly moving events, was it actually evidence of the issue? Or has the perpetuated image conditioned an immediate conclusion?

Don’t get me wrong, there is no denying that climate change is affecting the Arctic. But with this recent work, I’ve been primarily concerned with how that impact is portrayed in images and the complex challenges that come up when communicating changes in climate.

Frankly, it seemed to me, Svalbard had a bigger trash / pollution problem more than anything.

ED: I find your approach to your most recent work on such a difficult and enormous subject to be intriguing and fitting, using technologies whose limits are still quite unknown to investigate immediate problems whose full impact is somewhat of a mystery.

I’m curious where you’re finding inspiration these days? What/who are you looking at? What can you not get out of your head?

JL: Thanks for putting it that way back to me. That gives me something to think about.

Visually I can’t stop thinking about: Caitlin Cherry’s paintings for the way they get off the wall and become a literal defense system. Sarah Oppenheimer’s interactive sculptures, specifically at the Wexner. And I keep revisiting the photographs of Eliot Porter from his books on Antarctica and Iceland.

I also can’t stop reading Lars Jensen’s writings on post-colonialism, “Softimage” by Ingrid Hoelzl and Rémi Marie, “The Human Shore” by John R. Gillis, and “Concerto for the Left Hand” by Michael Davidson.

I’m in total research mode right now. Materials, essays, print methods, potential collaborations, fellowships, grants, etc. My creative practice is a venn diagram of research, making, and identity. Its at the intersection of these ideas where I find what interests me most, from art and science or art and economics, etc.

ED: How did you become so interested in economics? It seems to play an integral role in your work.

JL: Thinking about the economy of an image, or even how the local economy of the waterfront is performing, keeps me engaged in a practice of choice-making. Opportunity cost as an experience is not unique to most: If I buy this, I can’t buy this. How does one choice affect the next and so on?

But further, the kinds of economies that are “important” to a place, like the past and potential future of extraction economies in the Arctic, can tell you a lot in a short amount of time. They also become entry points into more conceptual questions: Who owns the land ? What is a landscape? Does the caught fish feed the person who catches it or does it get shipped away? How big is the network or reach of a place? These kinds of economical questions are actually part of my proposal in response to being nominated for a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship (SARF) at the Arctic Studies Center. I’ll find out in April if I make it to the next phase. Fingers crossed.

ED: Wow! Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship? That’s so exciting, congrats! I was just about to ask what you have in the pipeline. Anything else we can look forward to or follow you on?

JL: Thank you! Being nominated for SARF is awesome but nothing’s official yet. Otherwise, I’ll be showing in the window gallery at SPACE in Portland, Maine this Spring.

I’ve also curated an exhibition at 3S Artspace in Portsmouth, New Hampshire called “Freeze-thaw” this upcoming June will be showing new works with five other artists from The Arctic Circle residency: M. D. Acuff, Anna Clark, Rachael Dease, Brandy Leary and Cara Levine.

I’m on Instagram (@onedynamicsystem) and my website is http://onedynamicsystem.com. I contribute over at JONAA Magazine (http://jonaa.org) and The First Coast (http://thefirstcoast.org).

©Justin Levesque, Types of Ice I, archival pigment print from medium format negative + data manipulation, 20” x 24”, 2017

ED: Great to hear, Justin. Thank you for taking some time to share with us. This has been fascinating. I really appreciate it. Best of luck with all these new projects.

JL: Thanks for the interview, Eliot!

©Justin Levesque, Types of Ice I, archival pigment print from medium format negative + data manipulation, 20” x 24”, 2017

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025