Ken Weingart interviews Mei Xian Qiu

Today, we are sharing an interview that photographer and blogger, Ken Weingart conducted with photographer Mei Xian Qiu. Ken has been producing interviews for his Art and Photography blog, and he has kindly offered to share a his interviews with the Lenscratch audience.

Mei Xian Qiu is a Chinese, American, and Indonesian fine art photographer. Mei’s work is rich in metaphor and meanings, and she has had tremendous success. In the following interview, she opens up about her history and how her unique visualizations came to be.

Mei Xian Qiu is a Los Angeles based artist. She was born in the town of Pekalongan, on the island of Java, Indonesia, to a third generation Chinese minority family. At birth, she was given various names in preparation for societal collapse and variant potential futures, a Chinese name, an American name and an Indonesian name given by her parents, as well as a Catholic name by the local priest. In the aftermath of the Chinese and Communist genocide, the family immigrated to the United States. She was moved back and forth several times between the two countries during her childhood – her parents initial reaction to what they perceived as the amorality of life in the West countered with the uncertainty of life in Java. Partially as a result of a growing sense of restlessness, her father joined the U.S. Air force and the family lived across the country, sometimes staying in one place for just a month at a time. She has also been based in Europe, China, and Indonesia as an adult.

How old were you when you moved to the United States, and how has being Chinese and American informed your art?

I moved to the U.S when I was four to escape persecution in Indonesia. My family lived in Indonesia for three generations, since the 1880’s. Coming from a very conservative country, my parents wanted to frame their lives differently. Although they felt a certain exultation from this new freedom, they perceived the U.S. as an amoral place and not a place to raise children.

Hence, they gave all their children away, and I was sent back to Indonesia. My mother separated from my father and decided she wanted her family back. She and my father began the difficult process of reclaiming their four children. Since that time, I have moved back and forth several times.

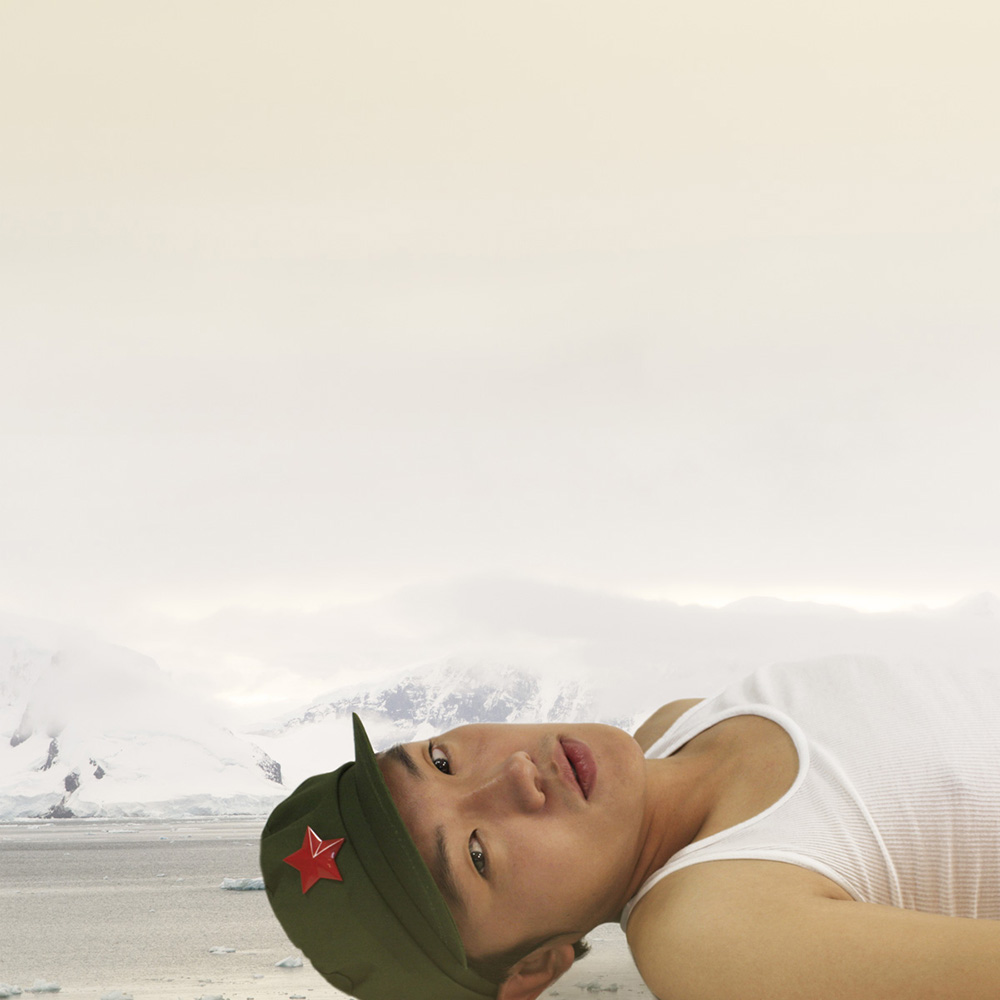

Inter-culturalism is interesting and often complex. My work stems directly from being Chinese, American, and Indonesian. My view of Chinese culture is necessarily fantastical, because I grew up where being Chinese was illegal and we had no access to Chinese culture in terms of traditions or morays. At the same time, we were labeled as Chinese and persecuted. In my work, I try to create a “Chinese” history in self-reinventions — skewed and out of whack, and completely unrestricted.

My main cultural identity has been American and Los Angelino, with a view towards the East like something out of a dream. My work is clearly American (as opposed to Chinese), especially in the way the subjects challenge the viewer with the directness of their gaze.

When did you become an artist, and how did photography start to play a role in that?

Probably from my mother’s belly! My caretakers would ask me to stop drawing and go outside to play with my friends. My life history posed questions that I had to tackle in an open handed way.

Photography was an outgrowth of painting. It is an ideal medium for me because photographs bombard an average 21st century human on a daily basis, combining commercial and political propaganda with images of personal and societal history. I find this daily merging of fiction and reality interesting. I want my work to have that illusion and connection to reality.

How do you like living in Los Angeles? What are the pros and cons, and is there somewhere else you would like to be?

Perhaps it’s the connection to cinema, but from when I arrived in Los Angeles at sixteen, I felt this freedom — this relative tolerance of differences, ideas, and exploration. It took me a few years to get accustomed to the landscape, the colors and the even the architecture, but I’ve now acquired a deep appreciation for these characteristics. I would like to be in a lot of places. I miss Indonesia for instance, but am unsure if what I miss still exists.

Your newest series Qilin and Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom have a lot of deep and diverse things going on. Can you distill for the layman what you are trying to say?

A simple distillation would be that the work presents an eroticized Rorschach to view our shifting perceptions, which are impermeable and unchanging. We live in an internal self-imposed landscape of an increasingly global monoculture. Who are we and what will we become, as seemingly indigenous cultural origins become more and more attenuated? Does our view of ourselves start to resemble how others view us at its most trite, streamlined and iconic?

A Qilin (Qi–male, lin–female) is an amalgamated Chinese creature, a hybrid of real and imaginary beings, and an ancient compass to the West. It pushes the work of Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom to its most dualistic, hybridist components.

In the image Cherry Blossoms from this series, there is a woman beautifully dressed in front of slaughtered animals. What is the meaning of this? Did you photograph the animals or have them imported into the shot?

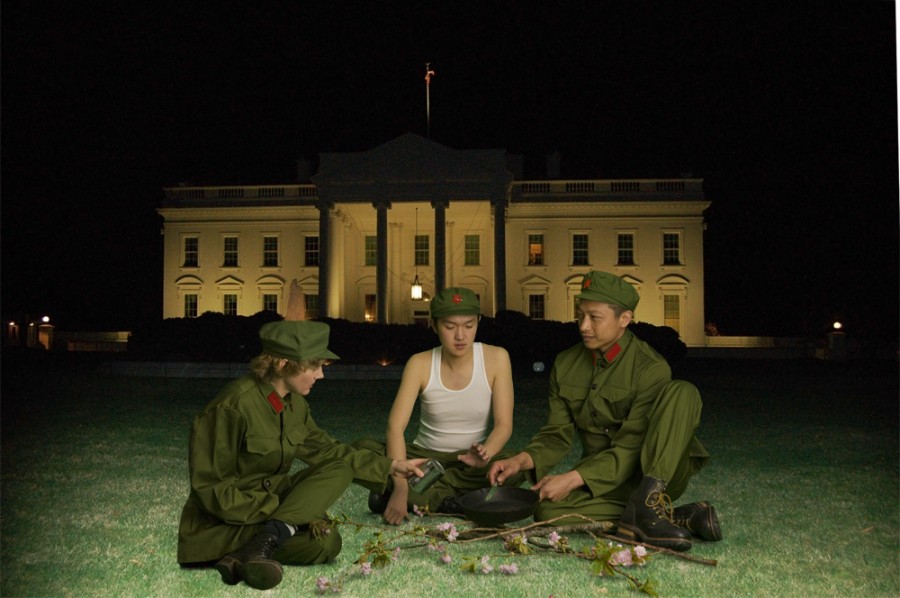

To understand this image, it is useful to look at the general outlines of the series Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom. Mao Zedong quoted a classic Chinese poem, “Let a hundred flowers bloom. Let a hundred schools of thought contend.” In a great society, different points of view and free expression should prevail. As a result, intellectuals and artists came out of hiding, living for this “beautiful idea,” even though they must have known it would be ultimately fatalistic, by creating a utopian kernel inside a dystopian vision.

The photographs portray a mock annexation of the U.S. by the Chinese, creating a hundred flowers movement here. The actors in the photographs are American artists or academics specializing in Chinese history — the very group targeted in the hundred flowers movement. The Chinese uniforms come from a Beijing photo studio where cultural revolution imagery is re-enacted by foreign tourists. The uniforms are brought home as souvenirs.

In this particular image, the woman is wearing a classical Chinese dress called a qipao, considered outmoded and “anti-modern,” in contemporary China, where Western pop culture and fashion are wholeheartedly embraced. She is holding cherry blossoms, a symbol of feminine domestic power and the dominance of beauty.

In image 8990, you have two gay soldiers, one Chinese and the other American, embracing in front of a deer in the forest. What is the symbolism here and did you use stock imagery for this background?

If soldiers were countries, what would they do? That was my initial question, since soldiers were sometimes the only contact one country had with another. Countries courted, fought, and got into bed with one another. I used two male soldiers because I did not want gender roles to be part of what the image was about, and I found it made sense formally as well.

In terms of the symbolism of the deer, they were associated with high remuneration and often historically depicted in Chinese art with government officials. I did not use stock imagery for the background. It is a bit of a play upon a play, with a slight dig at Chinese contemporary art — its political, moral, and aesthetic censorship, while its artists deal with issues such as control, war, and Western influence.

Image 8801 has a scantily clad woman in front of a poster of AK-47’s. Are you trying to juxtapose sexiness with war?

My work is most often highly subversive, dealing with popular iconography, stereotypes, and persistent viewpoints of gender and culture. War is ultimately about power. We have always been surrounded by stories in one form or another of sex, conflict and dominance—and the prestige that goes with it—that we use to define ourselves. If the function of an artist is to be a trickster of sorts, then we break down these stories and reconstruct them.

In this photograph, what has been made to be significant and what has been diminutized? In the lower right hand corner of the picture, there is a scattering of Chairman Mao badges that were once ubiquitous during the Cultural Revolution. Now they have been regurgitated as tourist souvenirs at countless Chinatowns around the world. Many of them have Mao’s 1962 poem written on them; “The plum blossom is delighted. The sky is full of snow.”

You are using the Plexiglas process for your prints. How did you learn about this, and what are the advantages?

My background is as a painter, and my photographs are quite painterly, with heavy layers of velvety pigment. The Plexiglas boxes were made to resemble a cross between three dimensional souvenir boxes and a reverential sort of stained glass. When I was a child growing up in post colonial Java, I would be woken at 5:00 a.m. to walk for an hour to the only Western style building in the village, a small cathedral (we had been converted from Buddhism by missionaries). At 6:00 a.m. every Sunday, the equatorial light would shine brilliantly through the stained glass and play upon the dust motes in the air.

To me, it held the magic and promise of the West. The variables of light through an image are important in my work, as they are a metaphor for the shades of identity and the multi-dimensionality of truth.

How was the experience at Art Basel? What happened and what did you learn?

I learned that the art world is small. You would consistently meet friends from different parts of the world at the fairs.

What do you want to achieve in the future, and are you working on a new series yet?

I would like to add sculptural and installation components. I want to keep working on my series, and follow it through its natural progression.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025