Now You See Me at Foto Relevance // Priya Kambli

This week, I’m honored to feature six artists who I had the privilege of curating into the group show Now You See Me at Foto Relevance, in an effort to offer a glimpse into the vast complexity and nuance of Asian America. While diverse in their image-making, the artists share a common thread: an urge to be seen and recognized through personal narratives put forth on one’s own terms. As viewers, the intricacies and variations in these narratives help us resist a monolithic interpretation of what being ‘Asian American’ signifies, stretching the term beyond its colloquial, demographic meaning (American citizens of Asian descent) and into a realm that pays homage to its activist roots. In 1968, a group of students at UC Berkeley—many who were influenced by and stood with the Third World Liberation Front, the Black Power movement, and the anti-Vietnam War movement—coined the phrase ‘Asian American’ as an iconic act of political self-determination. As the activist Chris Iijima said, “It was less a marker for what one was and more for what one believed.”

The exhibition is up at Foto Relevance through November 13th, but I hope you’ll join me in celebrating the artists and their stories for a long while to come. – Erica Cheung

—

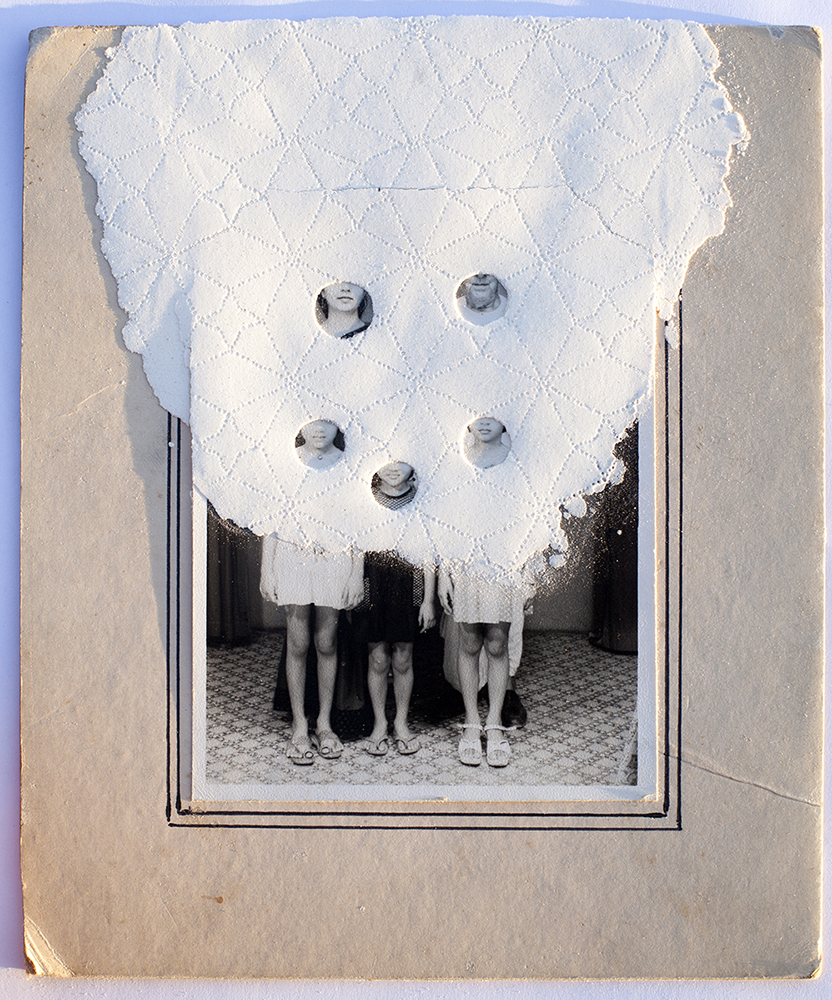

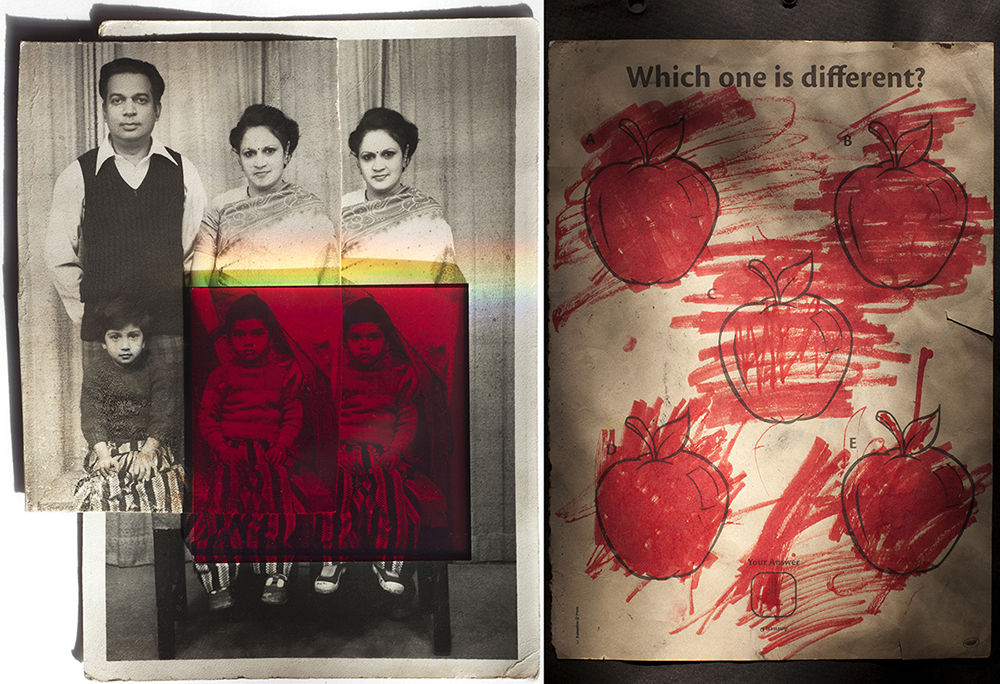

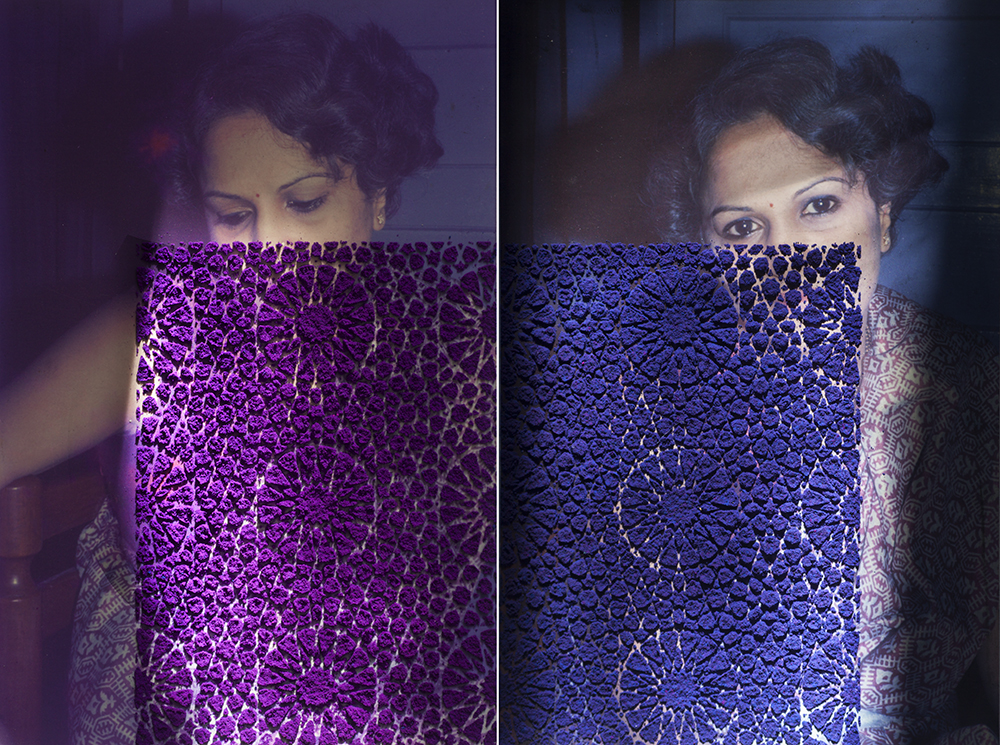

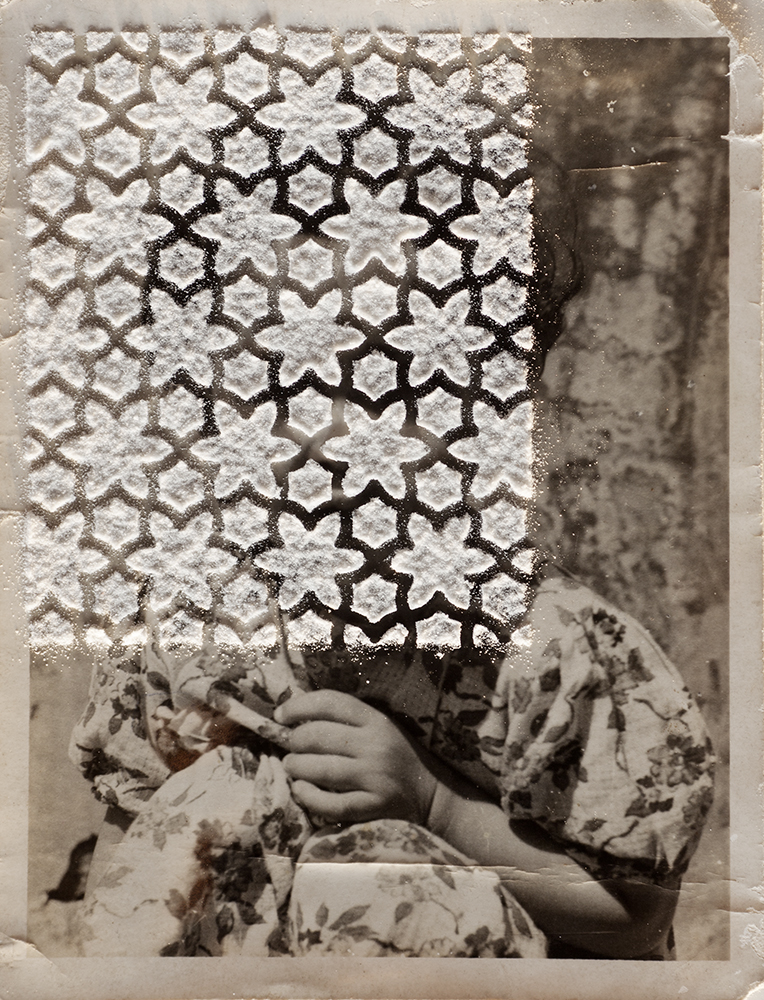

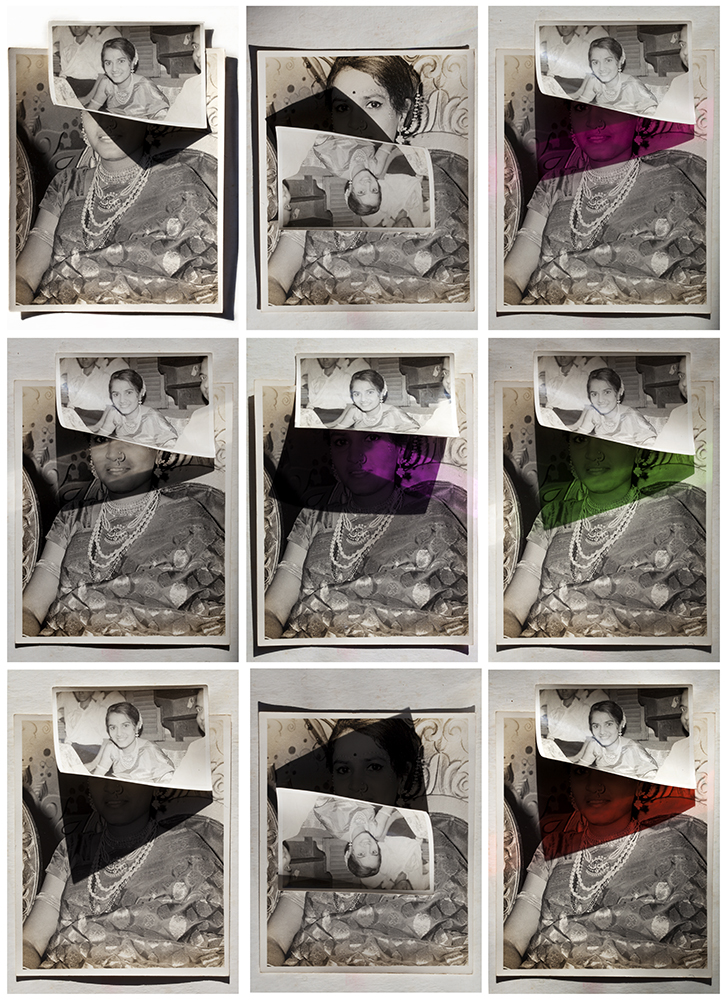

Today, I’d like to bring Priya Kambli into the mix. Through her series Buttons for Eyes, Kambli broaches large-scale issues of migration, visibility, and cross-cultural understanding through the intimacy of old family photographs and documents, combined with present-day portraits and still life imagery. As in much of Kambli’s work, a thoughtful attention to materiality underscores the series, realized through an abundance of playful interventions—from swaths of colored light to delicate geometries of powdered pigment.

I am constantly enchanted by the mesmerizing patterns and compositions aswirl in Kambli’s works, and am drawn to the care with which the artist visually mythologizes her family. An interview with Kambli follows.

Priya Kambli received her BFA at the University of Louisiana in Lafayette and an MFA from the University of Houston. She is currently Professor of Art at Truman State University in Kirksville, Missouri.

Kambli’s work inadvertently examines the question asked by her son Kavi at age three; did she belong to two different worlds, since she spoke two different languages? The essence of his question continues to be a driving force in her art making.

Kambli’s artwork has been well received, having been exhibited, published, collected and reviewed in the national and international photographic community. The success of Kambli’s work underlines the fact that she is engaged in an important dialogue, and reinforces her intent to make work driven by a growing awareness of the importance of many voices from diverse perspectives and the political relevance of our private struggles.

Buttons for Eyes

My work has always been informed by the loss of my parents, my experience as a migrant, and the archive of family photographs I brought with me to America. For the past decade, this archive has been my primary source material in creating bodies of work that strive to understand the formation and erasure of identity that is an inevitable part of the migrant experience.

My series Buttons for Eyes, in which my personal narrative is foregrounded – the title referring to my mother’s playful yet nuanced question, “Do you have eyes or buttons for eyes?”. It is a question laced with parental fear. Her concern was not only about my inability to see some trivial object right in front of me, but our collective inability to see well enough to navigate in the world. And with the benefit of hindsight those worries have political dimensions that may be read as implicit in the work. This work continues my effort to think about themes of identity, migration, and loss as catalysts for dialogue and the forging of cross-cultural understanding as well as its reflection on the broader cultural context. But the impetus for Buttons for Eyes, is the heightening of anti-immigrant rhetoric which has altered the context in which migrant voices like mine are heard. In this altered reality, the meaning of our personal stories has become political. —Priya Kambli

Thank you so much for taking the time to interview with me/Lenscratch! How have you been doing as of late? Where are you writing us from?

I am writing from Kirksville, MO a small, Midwest, rural and isolated community where I teach at Truman State University. I am fine- missing seeing art and my photographic community.

How did you come to include photography in your art practice? Why photography?

Photography has always been part of my upbringing; my father was an avid amateur photographer- who documented us consistently. My most vivid childhood memories are of standing beside my sister in front of my father’s Minolta camera- waiting, while he carefully framed and exposed us onto film. My father, an amateur photographer, took the task of making images rather seriously. And we (my father’s family) often found ourselves to be his unwilling subjects. Our reluctance was related to his perfectionism. We, his subjects were constantly herded from one spot to another, posed in one pool of light and then another. As a child I was certain that being photographed by my father was my punishment.

In the essay A Photographer’s Daughter– photographer Dayanita Singh talks about similar trials- of being raised in a family where her mother photographed her “just to validate her own experience”. This excerpt from her essay resonates with my own childhood memories.

“Being photographed was just another family ritual for me, and I had no interest in becoming a photographer. Photography meant that I had to sit still while my mother counted the footsteps towards me in order to focus her very old Zeiss Ikon camera. Every event had to be recorded in this painful manner, every departure delayed by her picture making.”

Interestingly, I find myself donning the role of the photographer, demanding that same commitment that I balked at hence most of my subject matter tends to be objects, artifacts or self-portraits, that I can put through a ringer without feeling that I am donning my fathers’ shoes.

My curation of Now You See Me at Foto Relevance is an effort to call attention to Asian American voices. What does the label ‘Asian American’ mean to you, and what does it mean for your art practice?

I think I identify with being as an “artist/woman of color”, and an artist working with the theme of migration via personal work, more so than an artist who is “‘Asian American” per se. While my work has always strived to understand the formation and erasure of identity that is an inevitable part of the migrant experience, I don’t see those as being particularly linked to that label, though increasingly they do seem to connect to the idea of being a woman of color.

How do other facets of your identity gel with, conflict with, and generally intersect with your Asian American-ness (if at all)? Do these additional identity markers influence the way you approach your work and/or the world at large?

When I migrated to America at age eighteen I was able to easily insert myself into the American culture. For me the transition from one culture at that time to another seemed seamless. Then the itinerant life contained within itself the comfort of the nomad – the sense that home is nowhere yet everywhere. But as I get older and go through new stages of life (marriage, motherhood, etc.) the need to anchor myself becomes fundamental and I feel my Indian identity reasserting itself.

Buttons For Eyes explores issues of immigration, loss, and cultural identity. Despite the heaviness of these subjects in our present sociopolitical landscape, many of your images are quite playful and buoyant. Why choose a playful approach in broaching these topics?

As you mentioned play is an integral and intuitive part of my creative process. To some degree I think the materials, which are so disparate, require that in order to make the artwork cohesive. You have to arrange and rearrange in order to get them to work together. And then in terms of the themes I am engaged with – they are very broad, they encompass the everyday, and the story of migration and cultural encounters is both heavy and light. There is pleasure and adventure.

A common practice across your portfolios is the act of mining your own treasure trove of old family photographs. What goes through your mind as you work with and physically manipulate these photographic artifacts? How do you select and design your various interventions—the light, powdered pigments, etc.?

I choose the elements I work with in a fairly intuitive manner, thinking about the potential they have to allow for interesting visual decisions. And then I do spend some time as I work with them meditating on who that person is, or what the associations might be with that object or material – and just as much time in a more abstracted frame of mind. I’m thinking about the meaning but I am also avoiding being overly precious or reverent. I can’t make the very best images if I’m overly worried about how I treat the materials.

What has been one of your favorite reactions or responses that someone has had to your work?

I have two favorite responses, the first from an essay Hereafter: Priya Kambli’s Kitchen Gods written by Jodi Throckmorton, Curator of Contemporary Art, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA for the Exposure, Journal for Society for Photographic Education. She wrote: “Kambli’s search through her family photographs is less a search for objective truth (though it certainly churns up common narratives of the diaspora) and more of a way to keep her ancestors ever-present.”

And the second is expressed by Madeline Yale Preston, independent curator, writer and arts advisor in regards to my series, Subha Mangal Savadhan via Critical Mass Juror Comments, where she mentions that the work from this series is “Like John Stezaker meets Dash Snow, meets… you!”

Whose work are you looking at and thinking about (from the Asian diaspora or otherwise, photographic or otherwise)?

I have also been influenced by writers and artists whose exploration of migrant narratives realizes their cultural, political, and societal impact. Among these writers are Maxine Hong Kingston, Jhumpa Lahiri, Arundhati Roy, Ocean Vuong and Zadie Smith. In visual art Jacob Lawrence’s “Migration” series of tempera paintings with text captions are elegantly restrained and raw; a body of work that I find both visually spell binding and enduringly relevant. In terms of contemporary photographers whose work I find compelling and which I return to again and again for inspiration, some are: Carolle Benitah, Tarrah Krajnak, Jessica Hines, Birthe Pionteka and Karen Miranda Rivadeneira.

What are you looking forward to? What’s next?

In the six months since schools & universities in Missouri shut down due to the Coronavirus I have followed the impulse, with great intensity, to create a new body of work titled Devhara using cyanotypes. The simple act of making art appears again and again to be my innate survival response to a crisis. The word Devhara loosely translates to mean a sort of frame or enclosure – a home for idols – in my native language of Marathi. In this series I am using the objects and idols from my mother’s devhara, to create abstract images/meditations/visual prayers. This body of work continues my effort to think about themes of identity, migration, and loss as catalysts for dialogue and the forging of cross-cultural understanding as well as its reflection on the broader cultural context.

The practice of mining an archive of images and the use of patterns – the infinitely variable warp and weft of Indian culture – have long been central to my work. In Devhara, these instincts diverge – moving from a photographic family archive, to a collection of objects. Instead of focusing on my father’s documentations, I am looking at my mother’s objects of worship. And I am moving from the use of pattern as a representation of culture to pattern as acts of welcome, to express gratitude, ask for forgiveness, and to remember.

I have a show opening at the UNF Gallery at the Museum of Contemporary Art/ Jacksonville, FL in March 2021, at artist residency that was rescheduled for May 2021 at the Visual Studies Workshop, Rochester, NY.

Social:

IG—kambli.priya

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

McCall Hollister in Conversation With Douglas BreaultMarch 6th, 2026

-

Greg Miller: Morning BusMarch 5th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Lindsay MetivierFebruary 21st, 2026

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026