Now You See Me at Foto Relevance // Tomiko Jones: Hatsubon

This week, I’m honored to feature six artists who I had the privilege of curating into the group show Now You See Me at Foto Relevance, in an effort to offer a glimpse into the vast complexity and nuance of Asian America. While diverse in their image-making, the artists share a common thread: an urge to be seen and recognized through personal narratives put forth on one’s own terms. As viewers, the intricacies and variations in these narratives help us resist a monolithic interpretation of what being ‘Asian American’ signifies, stretching the term beyond its colloquial, demographic meaning (American citizens of Asian descent) and into a realm that pays homage to its activist roots. In 1968, a group of students at UC Berkeley—many who were influenced by and stood with the Third World Liberation Front, the Black Power movement, and the anti-Vietnam War movement—coined the phrase ‘Asian American’ as an iconic act of political self-determination. As the activist Chris Iijima said, “It was less a marker for what one was and more for what one believed.”

The exhibition is up at Foto Relevance through November 13th, but I hope you’ll join me in celebrating the artists and their stories for a long while to come. – Erica Cheung

—

The final artist I’d like to recognize is Tomiko Jones, whose work embodies a quiet expansiveness and a longstanding connection and familiarity with the landscape all around us. Her series Hatsubon is a multimedia installation for her father, hovering in the colliding spaces between ritual and performance. Black and white landscapes materialized on floating silk, hand-fashioned wooden vessels, and rounded waterscapes reflected in mirror pools bring forward the tradition of O-bon—a Japanese Buddhist tradition for honoring and sending off one’s ancestors—into contemporary life.

I treasure the vulnerability and openness with which Jones creates. It is an absolute wonder to spend time with and to be moved by her works. An interview follows.

Tomiko Jones’ photography and multidisciplinary installations explore social, cultural and geopolitical transitions in the landscape, and considers the twin crises of too much and too little in the age of climate change. Her current research, These Grand Places, is a socially-engaged investigation of people and place on public land. Her recent project Hatsubon is a memorial exhibition in photography, video and sculpture.

Currently Jones is an Assistant Professor at University of Wisconsin-Madison and on the Board of Directors, Society for Photographic Education. She received her MFA in Photography with a Certificate in Museum Studies from the University of Arizona, Tucson.

Hatsubon

Hatsubon is a memorial exhibition exploring the dynamic tension between tradition and performance through photographs and objects. The work lives in the diaphanous space between life and death, and is a memorial for my father. The materiality of the works suggest the dualities of the fleeting and the lasting, the ephemeral and the corporeal, and the pendulous state between longing and release. —Tomiko Jones

Throughout time communities and cultures have sent many of their young ones off to sea to find a better life on the other shore; at the other end of a lifetime, the ocean is home to our many rituals of death, both vehicle and destination for the final journey of our loved ones. With this body of work we travel to Jones’ unnamed coast—where the river meets the sea—to ritually set free the spirit and body of her father. —Deirdre Visser, Curator of The Arts at CIIS

Thank you so much for taking the time to interview with me/Lenscratch! How have you been doing as of late? Where are you writing us from?

Thank you for the opportunity to speak about my work. I’m writing from Madison, Wisconsin. Despite the increasing COVID-19 cases and attempts at voter suppression in the state, I guess I’m doing alright. I’ve been exploring the regional watershed and it’s a stunning autumn. Yesterday I paddle boarded down the Kickapoo River as it flows through both the Kickapoo Valley Reserve–which is managed by the Ho-Chunk Nation and the State of Wisconsin–and Wildcat Mountain State Park. The river and surrounding environs are sites of ecological restoration on public land. It was so peaceful with autumn leaves falling under a crystal blue, cloudless sky.

How did you come to include photography in your art practice? Why photography?

I like how you framed this question–why photography? I paused on this for some time, trying to ask myself “why?”, which led to a string of memories of cameras and tools given to me by family. When I was in 3rd grade, my parents gave me a tiny point and shoot film camera. I remember keeping it in a Tupperware container that belonged in a lunchbox. When we moved to my grandmother’s house in Hawai’i for a while, I took pictures of everything. Back in Washington in high school, my Geometry teacher made a makeshift darkroom in an old classroom. My father gave me his Pentax K1000, which came on road trips we took every summer to national parks and cities along the way, so I could take the class. I challenged the school to let me take that class as my occupational therapy credit, substituting it for typing. “I am going to be a photographer, not a secretary!”, I remember claiming in an interview with the superintendent, and followed it up by examples of National Geographic and an article about RIT. I somehow managed to convince them, although I still can’t type!

I left home shortly after turning 17, and for my 18th birthday, my parents gifted me my own camera. This was a huge deal! I went to college but couldn’t get into a photography class as I wasn’t a major, so I used a community darkroom tucked under a stairwell built by the curator Rod Slemmons (although I did not learn that until years later). I worked in there at night and on weekends for a year until I could weasel my way into a class. That same year, in February, my grandmother became ill, and although I was already planning to spend the upcoming summer with her, there was the sense that time was short. I bought 100’ of black and white film and went to Hawai’i with my family. I think this may be when and where it solidified. I knew, almost as an instinctive feeling, that this was a very important tool to understanding the world, my own identity and place within it, and as a vehicle in which to express myself. In this case it was in coming to terms with the loss of my grandmother and with it, generational knowledge. With an infallible memory, she was the keeper of stories. I remember recording conversations with her, asking her to “talk story” about our history.

A few years later, my youngest uncle, who was an inspiration to me, died suddenly and my aunt gifted me his Minolta 35 mm film camera. “He would’ve wanted you to have it,” she said. That was my camera for many years, and in my early freelance years it was my workhorse. The environmental movement was in full swing in the northwest, and I photographed landscape, activism, counterculture, and, of course, grunge. I also continued to use a Rolleiflex (twin lens medium format camera) and vintage and toy cameras. Seven years after my grandmother’s passing, we attended a Japanese Buddhist seven-year service, and I brought with me everything I needed to stay for months, fulfilling the promise I made so long ago.

While there, one day my uncle invited me to come over, and asked, “any of this you like?” gesturing to boxes of cameras, an enlarger, trays and everything I needed for a darkroom. I built a makeshift darkroom in the sewing room in my grandmother’s house and taught myself 4×5 tank processing. I barely knew how to use the camera, but fortunately had a lesson with Ken Ostheimer and had looked into the ground glass on Neil Chowdhury’s camera back in Bellingham, WA. It’s interesting to write this now, because this same uncle passed this past spring, right when I had been using the same enamel trays he gave me back then to process prints in my quarantine home studio. The reason I am telling you this long story is because I feel like photography kept coming to me. I was already identified as the family photographer and recorder, and it was a tool for me to better comprehend my own mixed identity, my attachment to cultural tradition, and my desire to locate myself in place. In some ways, this has never changed over all this time in my practice, although there is more nuance to my approach and choice of mediums.

My curation of Now You See Me at Foto Relevance is an effort to call attention to Asian American voices. What does the label ‘Asian American’ mean to you, and what does it mean for your art practice?

Thank you for this question; it’s a layered answer. I was not aware of this label until I was in college, which was during the Culture Wars, the first wave of “politically correct” language when identity politics had reached the mainstream. I was used to talking about myself as hapa, or in terms of how many generations my Japanese family had been in the US territories as issei, nisei, sansei, yonsei. I also thought of myself more simply as Pacific, with the connection to a larger immigration pathway. Up until hearing “Asian American”, I had primarily been identified as “minority”, and a little later as “multicultural”. Generally, I found these labels confusing, in part because I had always had a hard time finding where I belonged and answering the dreaded “where are you from?” question. Home was abstract. It felt impossible to locate myself belonging to any particular place. This search for a sense of belonging has ultimately defined my practice. I am able to find connection everywhere, yet do not belong anywhere.

In my art practice, I draw influence from Asian, specifically Japanese, design, aesthetic, philosophy, material use, and the cultural traditions of my lived experience. It is not always as overt as in Hatsubon, but it remains an undercurrent throughout.

How do other facets of your identity gel with, conflict with, and generally intersect with your Asian American-ness (if at all)? Do these additional identity markers influence the way you approach your work and/or the world at large?

Over the years, I’ve become conscious of the comfort I have when I meet other Asian Americans, whether it is walking on a trail, in a store, in a gallery. Take us meeting for the first time, I was immediately open to you, it just seemed natural and easy. I find a similar comfort in ritual and tradition, in how I move through the world, whether it is in “everyday” life or in the studio. I feel the intersection of contemporary and traditional, though could conflict, has a beneficial influence on my work. Although I am attached to my work in terms of being the maker, I also find I am detached because I feel it is so much bigger than me, and could not possibly have come into being without the spirit of those who came before me. In this sense, this way of thinking allows me to not be too worried about recognition or success, or about making something original. It’s a bit like a de-emphasis on individuality or authorship, and I wonder if this is why I value collaboration so much. Does it come from my cultural identity or my upbringing or something else, or is it an intersection of all facets?

Hatsubon is a memorial project complete with multiple forms of media: photographic prints on silk, reflection pool-like video installations, and hand-carved wooden objects, among other pieces. How did the distinct materiality of the series unfold?

My choice of materials is considered in all of my work. The two are in symbiosis, at times the materials guide me, at others the content guides the materials. I gravitate towards natural materials for their texture and tactility, and the animistic sense a material imparts, that brings me closer to the source, and in ethical terms, I think about my environmental responsibility.

I like working with my hands, and the process by which I arrive at something is important, whether it is the material or the tool. I’ve thought a lot by why I am so influenced in my choices and come to think it is from things that were both familiar and from afar. Growing up we had scroll paintings, dolls, ceramic and paper sculptures in our home, we wrapped packages for omiyage (gifts), folded origami for friends, and celebrated O‐bon, the ceremony for the ancestors. Aesthetics were also domestic, and practiced in the kitchen, especially for important occasions. Growing up between the west coast of the US (Washington and California) and Hawai’i shaped my identity throughout my childhood and the influence of Japanese design and materials is apparent in my work, from papers and patterns to carving and printing woodblocks.

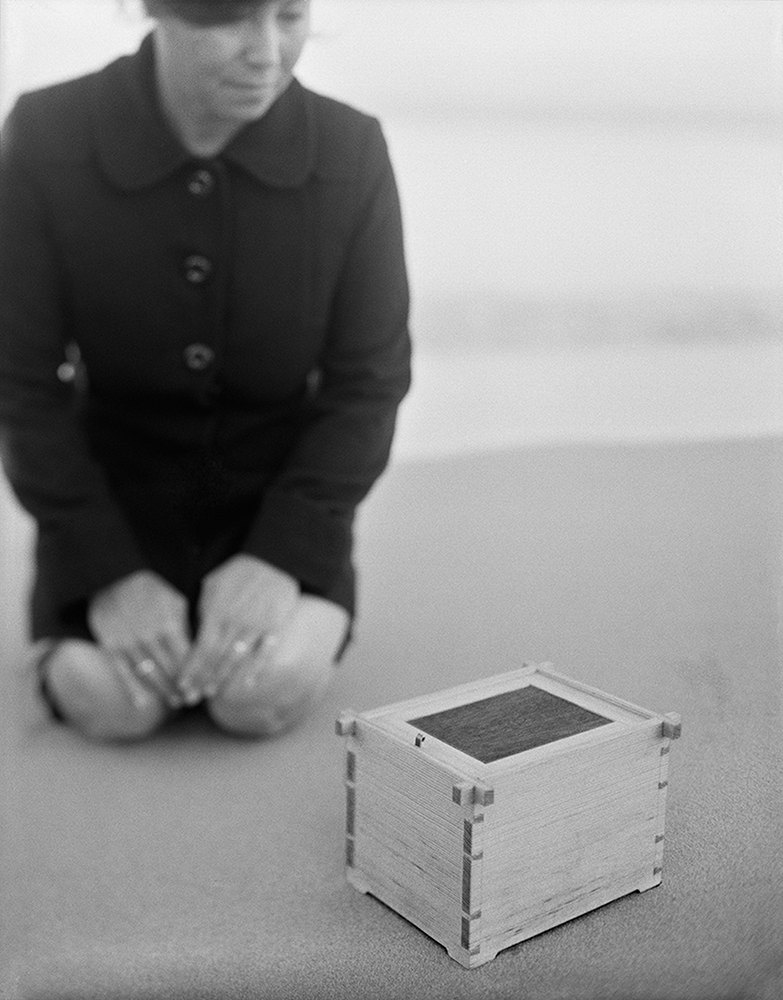

To briefly describe choices in Hatsubon, I felt early on that there would only be a handful of large images, and these would be keys into the work. Printed on silk, these diaphanous, translucent images are suspended off the wall and reference the veil between the living and the deceased. Other images were printed on paper, visually heavy and tactilely physical as the body, in floater frames made with walnut, my father’s favorite nut. Pictured within the photographs are objects such as the shoryobune (ritual vessel) constructed of bamboo steam bent it into the shape of a boat and skinned with kozo, a common Japanese paper made from mulberry, and my father’s urn, made of Douglas Fir, a regal tree seen from my his window. “The Oar” came from an end of life conversation with my father. This could not be a photograph; it needed to be an actual object. The act of carving away, a reductive process, was cathartic; moving with the grain of the wood and shaping it slowly and with tenderness. It is made with cherry and cut to the length of my body.

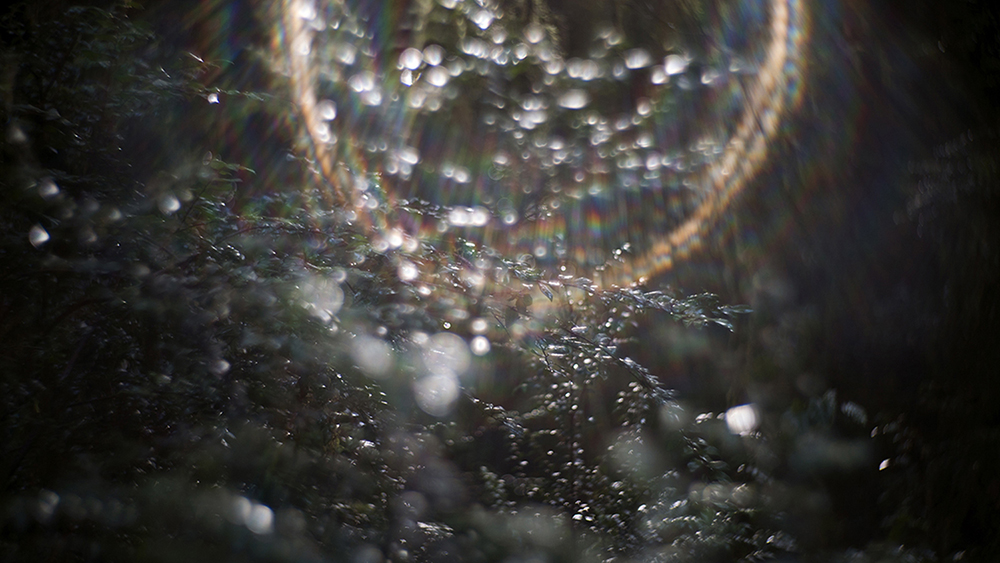

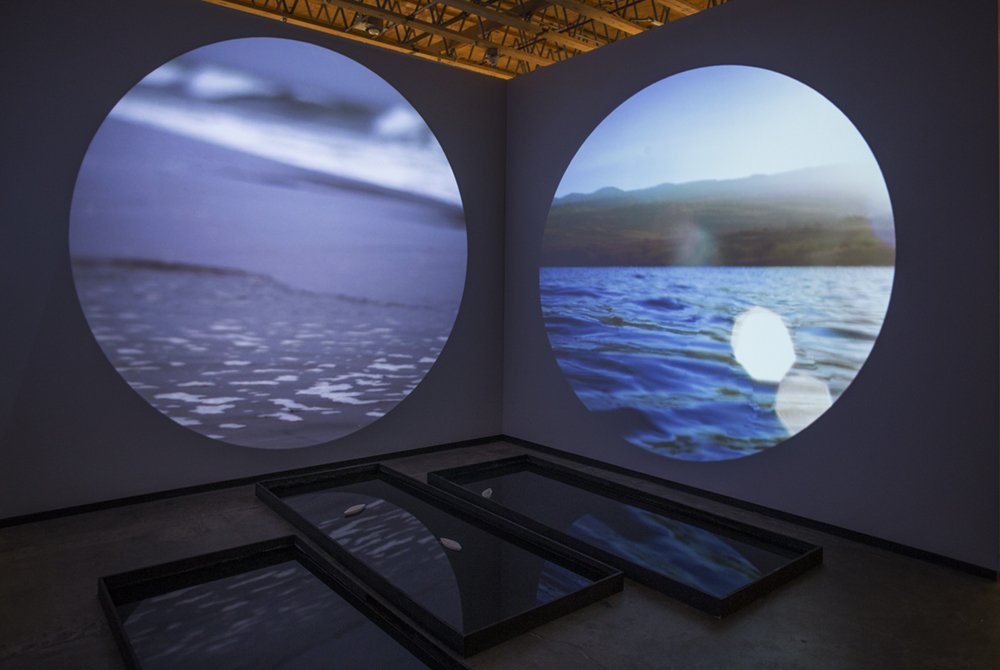

Next, I needed to make him a boat to fit his body. I came to the idea of the skeleton form and used ash, the tree of life in the Gaelic tradition, in honoring the Jones side. Once I started to form the boat with steam bent lengths of ash, I saw the body come to life. I had made cross-braces, but once the ribs were in place, I knew it was finished, and stopped. It sought to be simple. In this way, I let the materials guide me. The video installation, with three projections on moon-shaped scrims mirrored in reflection pools echoes the concept of the memorial, and the spiritual association with water. Within the videos (and photographs) are three sites of significance: Pennsylvania, my father’s birthplace, along a river he grew up on; Hawai’i, my mother’s birthplace where we set the boat to sea, and where he is buried; California, where my parents met and I was born. The dimensions of the reflecting pools indirectly represent the toba, or memorial tablets, on which the names of the ancestors are written. The repetition of three is tied to the women holding my father through life and death: my mother, my sister and myself. Other objects are small slip cast porcelain boats that help move us through the images. The entire installation is lightly orchestrated by miegakure, the concept of concealment or “hide and reveal”.

Ruminations on place and how we might relate to the broader landscapes around us seem to underscore much of your work. Will you speak toward your relationship with the land and how it surfaces in your art?

You have captured it through the word “ruminations”. I find in the landscape parallels of my own experience. I look for transitions–in-between places where change is actively happening, places that are neither here nor there or this nor that; where dark meets light, land gives way to sea, sea to sky, where a scar on the land repairs itself, where a mountain has been reduced to a pit of mined earth, where a stream finds its way under a housing project, where a forest springs up after a wildfire.

I explore transitional spaces and the human connection to the sites we inhabit, utilize, work and play in. I source material from each location to create a conversation between place and image, at times using the sun as my light source and existing water to process, or inking and imprinting found objects onto paper surfaces.

I investigate the construct of land as ownership, aware of my own status as visitor on this colonized continent. What is place, placeless, displaced, replaced, misplaced, in place, out of place, sense of place? I am concerned about the state of the planet, and in my research, I draw on natural, social, cultural and political history. Although my work is not documentary, this research figures into my practice.

Working in the landscape is instinctual, familial, cultural, memorial. Here I can create loose mappings that echo the internal terrain, and see cycles and systems that repeat in human existence. I think about how nature provides respite and can give a sense of peace. It gives comfort as it renews and restores. I have dwelled on these ideas for decades, yet now the experience is widely shared as people flock to the outdoors, one of the safe places during the pandemic. We ask for so much. What do we return?

What has been one of your favorite reactions or responses that someone has had to your work?

I can answer without pause, that the deeply personal responses that people have shared with me with Hatsubon has been profound. There is something that allows people to share their own stories of loss, grief, pain, love. I have heard stories from strangers and cried with them, and received beautiful messages and sometimes even gifts. I was terrified when I first showed this work, I felt so vulnerable to have my family in the work, and the privacy of ritual and grieving made so public. The compassionate response of others has given me strength. I have said before that I felt guided in making this work. I know it has affected the way I am working today.

Whose work are you looking at and thinking about (from the Asian diaspora or otherwise, photographic or otherwise)?

It’s interesting to see how quickly Asian artists populated my list after you asked! I thought of Rinko Kawauchi, who I have been looking at lately, which led me to Masao Yamamoto, and then Cai Guo-Qiang. I thought of how I had wanted to study with Patrick Nagatani in New Mexico. Then Sophie Calle, Roni Horn, Louise Bourgeois came to mind as go-tos, which made me think of the elders and the lineage of influence, but that’s a longer conversation. Currently I am doing more reading–on my nightstand is “Back Roads to Far Towns” by 17th century poet Basho, “Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape” by Lauret Savoy, and a gift that arrived in the mail from friend and cultural historian LisaRuth Elliott, “This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent” by Daegan Miller. All three are undeniably tied to my current research.

Recent “wows” that come to mind are Isaac Julien’s “Playtime” (Fort Mason, San Francisco), an exhibition of objects and narrative paintings influenced by “The Tale of Genji” at the Met (New York), and Garrett Bradley’s “American Rhapsody” (Contemporary Art Museum, Houston). I can’t wait to see “The Raft” by Bill Viola next week (Chazen Museum of Art, Madison), and was sad in the past year to miss the somewhat nearby exhibitions of Dawoud Bey’s “Night Coming Tenderly, Black” in Chicago and “Graciela Iturbide’s México” in Minneapolis. Iturbide’s work was one of the first exhibitions I saw when I was learning about contemporary photography, and it left a great impression on me. Around the same time, I saw a retrospect of Paul Klee, an installation by Ann Hamilton, sculpture by Isamu Noguchi, and a James Turrell Skyspace.

What are you looking forward to? What’s next?

I am looking forward to immersing myself more deeply in a project that has been moving along slowly the past few years, but is developing into a sustainable, longform practice. I’m a bit behind schedule with the crises of this year, but I should be on the road in early spring, and I’m excited!

Public lands are part of our national identity, and they are under threat. On January 30, 2017, President Trump announced a reorganization of government agencies, including the National Park Service and the Department of the Interior. By April, there was an order to review use of public lands and to recommend deregulation. This filled me with a sense of urgency, not to rush to photograph these places before they are gone, but rather to document through my art who uses the land, and how they use it. I began to map out a plan to visit sites under federal review, leaning on the methodology that guides my practice—taking time to listen and experience, rather than dropping in and assuming knowledge or taking the colonial approach that precedes me, the one that built the system that in part exploits, and in part protects.

Preliminary trips to several locations prompted the idea to build a better system to work from. These Grand Places combines art, science, and technology in a mobile research studio to conduct research through on-site residencies on public lands in a manner appropriate to the environmental intention. This live/work space is equipped with digital and film cameras, drone, laptop, small printer, UV light unit for alternative processes, video projector, and a portable kit for public workshops. The studio uses solar power to run appliances, lights, equipment, and recharging stations.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024