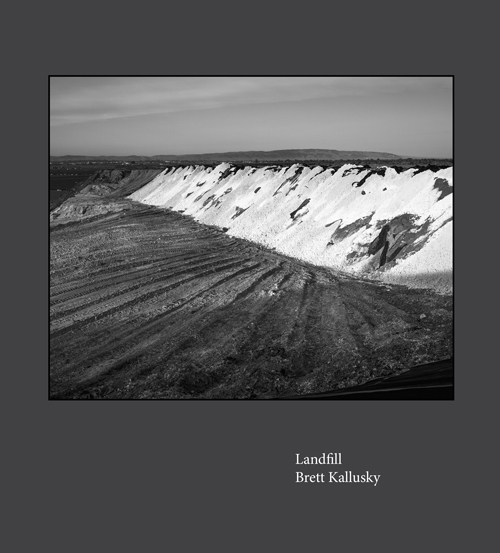

Brett Kallusky: Landfill

Landfill: Elegy for the Santa Maria Valley is Brett Kallusky’s second photography book, published by George F Thompson. The photographs and essays direct our attention to the large-scale agricultural productions within this Central Coast California region and the garbage and industrial waste that comes with it.

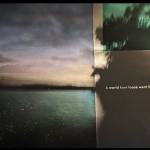

Although many of the images take on a deadpan approach of showing the Santa Maria Valley’s lifeless landscape of leeched soil and plastics, there are also intimate close-up images that evoke more sentimental queries. The photos are bold and subtle but collectively invite us to take a closer look at the harsh realities of the extraction and production processes that occur at all costs for consumption. Kallusky reminds us of our cyclical relationship with nature, one of life and destruction.

The following are excerpts of a conversation between Sarah Knobel and Brett Kallusky discussing his photographic practices and philosophies that are depicted through this series. Both Sarah and Brett participated as photographers in the 2022 Review Santa Fe.

Follow Brett Kallusky on Instagram @brettkallusky, Follow Sarah Knobel on Instagram @sknobel

Brett Kallusky was born in 1975 in St. Paul, Minnesota, and grew up in Afton, Minnesota. He completed his B.F.A in photography at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls and his M.F.A. in photography at Cranbrook Academy of Art. Since 2007, he has taught photography full-time while maintaining an active photographic studio practice. He is currently an associate professor of art and Art Department Chair at the University of Wisconsin-River Falls. His photographs have appeared in Aint-Bad Magazine and National Geographic Online, and his previous book is Journey with Views/Viaggio con Vista (self-published, 2014). Kallusky has been a Fulbright Fellow to Italy, received three Minnesota State Arts Board Artist Initiative Grants and numerous Faculty Professional Development Grants from the University of Wisconsin-River Falls, and is a two-time finalist for the McKnight Fellowship for Photography and Visual Arts. He resides in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

SK: What made you start this project? You mentioned you have been working on this work since 2013; I’m curious about how the work changed over time. Did your imagery change as you gained knowledge of the area and agricultural processes?

BK: In terms of encapsulating the conversation – I think it’s important to note that the work was done over six years in terms of shooting, editing, and reiterations of presenting the work through exhibitions and mini publications. It took quite a while. Returning to that same place to make those images was not something I eluted soil from oil spills along the Pacific coast. It was simple – he said he had someplace to show me. He knew I was a photographer and took me to this place. It is an age-old story – sometimes for better or worse, but I had a naïve curiosity about this place. It started as just looking, but as I returned, I saw things that made me want to return and make images.

I had full access, which I never really experienced before as a photographer. I had access previously (to a certain extent) while I was doing photographic work in Italy. But before that, all my photographic work was based around transgressions. Transgression of going into spaces that weren’t available for public viewing or consumption. So having access gave me the drive to spend more time, and do the work that I did. I started off working purely digitally. I realized I needed to work with a large format camera to fully analyze what I was looking at and slow down/reflect on that process. I honed in on the quality instead of the quantity of images I was making.

SK: Some of your work has a similar sensibility to Robert Adam’s images and other New Topographic work we saw in the 70s. You give your audience a detailed depiction of man’s manipulation of the land. You also have some intimate images, such as the falcon, the tobacco plant, and the house, which seem to have stories behind them. We usually think of this California area as filled with idyllic landscapes. But these more intimate images also remind me of FSA images of the great depression. Can you speak to your process of photographing for this series?

BK: I’m glad you picked up on that; it makes me happy. This comment makes me think on the trajectory of my work over twenty years. I think of my time at graduate school at Cranbrook Academy of Art – an incredibly beautiful place to study; it was full of energy and creative power. My cohort are amazing people and truly a gift in my life. But also, Cranbrook is surrounded by Bloomfield Hills – one of the top five wealthiest communities in the country. It is an island of art in a sea of new money. I would drive to Flint, Michigan, forty-five minutes north, for my thesis work. From 2003 to 2005, there wasn’t much photographic work about Flint. Michael Moore had made Roger and Me – which put it in my consciousness as a place to see. I was witnessing this contrast of wealth disparities as I made my work.

My work during my Fulbright in Italy documented or re-photographed (I use that term loosely) the landscape photographs that the Alinari Archive created in the nineteenth century. During this time, the term ruin porn came up; I felt self-conscious of being an outsider – I still do, and I use that as a mechanism for my work as a photographer – meaning, I’m not ever comfortable with what I am doing. I never let myself feel comfortable, even with repeat visits to a place. I am not from that place. A comment came up at a book signing regarding the tradition of white male photographers to make work out west. I get that; on the one hand, and can say it is part of a trope.

On the other hand – being from Minnesota, where we have so much water and fertile landscape (as well as landfills and pollution) – it is vastly different from what I witnessed and analyzed of the landscape in California. That’s always the approach in my work – how do I pull myself from what I’m used to? What makes me feel at home or feel safe? Where I make my work is not my home – I feel on edge. The point you bring up of the house image or close–up detail shots is taken from or made from the perspective of being unsure or not being used to what I was looking at.

SK: And you don’t show any people. There are signs of people, maybe a movement of a person, but not a focus on the people. I’m assuming that is intentional, or did you take pictures of people but decide not to include them?

BK: You are right; this is totally intentional. I think one of the first conversations I had about that was with Yasufumi Nakamori, then curator of Photography and New Media at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. He asked me where the people were. My statement then is the same as it is now – that is not my story to tell. Not that I am unaware of migrant labor, or unaware that people are equally a part of and an important part of the story as the land itself. The political context in which I was making the work needs to be seen. Half of the work was made when Trump was president. It was made in 2016 through 2019, and I felt it. Driving to photograph the Salton Sea – I went through a border checkpoint and felt nervous. But I’m the person that has the least to worry about in terms of who I am. That made me think about what impact I was having – rolling up in a rental car by a field to make photographs; I did consider what the people there might be feeling. It ended up, for me, being around empathy more than anything, which is why there are no portraits. At the landfill, I did get to know someone personally, but I didn’t want it to be about that – politically, sociologically, or artistically for that matter.

SK: And, going back to it – your work is the story about the land and how we are manipulating the landscape –– you get a sense of people being a part of it, but it feels apocalyptic. Humans are there but are they really there?

BK: I’ve always been more interested in the traces left behind by people, rather than photographing people themselves. The fact that the farming community is so massive and at such a scale that feeds millions of people – it is a little dehumanizing to see acres and acres of plastic covering. It is also dehumanizing to be in a largely arid place and know that there is this process of extraction at all costs for consumption. I’m not saying that it shouldn’t happen – you asked earlier what the main point I would want the audience to take from the work. I teach at a primarily agricultural university; I’ve talked to my students who have grown up on farms – and they have asked if the work is anti-farming. Landfill plays and works with the idea that farming and agriculture is necessary, but how it is being done needs to be absorbed, and hopefully evaluated. The water use data for strawberries from 2019 around Santa Maria was 19,850 acres/foot. One acre-foot equals 325,851 gallons of water being used in areas that don’t have a lot of water, which is mind-blowing to me. It’s on a completely different scale. It is also a point of wonderment and goes back to the idea of being uncomfortable. What does it mean to use that much water on food which is unsustainable given the climate realities?

The apocalyptic point you also make ties into nostalgia. The photographs of the strawberries, the house, and the signs are what we think of as home, and comfort in relation to food.

SK: Your work shows your viewers processes and spaces we usually do not see when we consume. I’m curious about some of these things I’m looking at – like the images of the reclaimed soil; what is it exactly?

BK: NHIS – Non-Hazardous Hydrocarbon Impacted Soil. The term of dead soil is best way to describe it.

SK: Do they reclaim and reuse it on farms?

BK: No, it is reclaimed from polluted areas and put through a high-pressure cleansing process with water and chemicals. So this shot shows Sun Luis Obispo, where Frank Aston’s Union Oil Tank Farm image was taken, which was one of the largest natural disasters of the 20th century. The soil you see that looks chalky, I think it looks like dinosaur bones, is from that place in San Luis Obispo. It just goes into the landfill – tons of it, lined and capped. And where you see the tobacco tree that is on top of it. The reality is this image is an homage to a story I heard. I was told that at one point, a small township asked if it could use the landfill for human waste that had gone through a waste treatment plant. The waste had been cleaned, essentially being used as manure for the topsoil. The next year, there was corn, watermelon, tobacco, tomatoes, and tomatillos growing out of the soil. The workers asked if it was safe to eat, and it was. The seeds went through people’s digestive systems. It’s gross, but the human digestive system is one of the most intense destructive environments on earth. The seeds survived that and subsequently survived this man-made treatment process and still grew on top of this landfill. The big picture is -whatever we do to the land over time, ultimately can only hurts us, but not these natural processes – I’m talking epoch time, not decades or years.

SK: So, Landfill is about this specific area: the destructive history, the reclamation of the soil, farming on a large scale, the landfill that is strained with the production. But what you just said also represents an idea of the cycle of life – we manipulate our earth, and there is death but also life.

BK: That is a great way to describe it – I like to keep it narrowly focused, but what a big cluster fuck for humanity at this point. I must focus on one or two places to be able to show the content with any reasonable clarity. I thought of it as throwing a stone at a pond. And going back to your question of how you want the work to serve, awareness is part of it. I also think about mediation and what it means to meditate on a place or idea and be present with it no matter how uncomfortable it is.

I’m a big fan of the Buddhist Priestess, Pema Chodron. She talks about the clarity you can find through meditation – the idea of clearing the storm and clearing the fog out of your mind. She talks about it as a double edged sword – once the fog is cleared and you are looking at the clear pristine lake, you see all the skeletons and rusty bicycles there.

In that sense, my publisher wanted the book to be called requiem. The word requiem was too catholic for me. I’m not religious; I’m a secular Buddhist – it’s how I approach life. He said Elegy – and I was okay with that. Although it still sounds religious, it gives the potential that this could transform, or show a cycle that would be transformed into something more positive.

SK: But Landfill was the final name – can you tell us why?

BK: I wanted to go with Sugar Street, the street where the landfill is, and I thought about how funny that is. Sugar has its own history – a sordid history as well. Landfill – partially is what it is, but as a metaphor, I thought a lot about Robert Smithson and what a site is, and opened the title up to further interpretation. The land is our understanding of terra firma, but fill is both what we put into the land itself, and also what we want to put into it, in a way. I was trying to go for something simultaneously specific but also ambiguous.

Take a closer look at Brett Kalusky’s beautiful and subtle but complicated photographic work on his website.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

2023 in the Rear View MirrorDecember 31st, 2023

-

The 2023 Lenscratch Staff Favorite ThingsDecember 30th, 2023

-

Inner Vision: Photography by Blind Artists: The Heart of Photography by Douglas McCullohDecember 17th, 2023

-

Black Women Photographers : Community At The CoreNovember 16th, 2023