Dana Smessaert: An Obligation to do One’s Best

This week, we will be exploring projects inspired by place. Today, we’ll be looking at Dana Smessaert’s series An Obligation to do One’s Best.

I met Dana Smessaert in the Gray Gallery a week before classes started at East Carolina University. We had lunch together, and honestly, we didn’t separate until two and a half years later, sharing a studio space, duplex, and breakfast on the weekends when we both graduated. Dana is an extremely passionate artist and educator. While they are meticulously trained in traditional photography, their use of interdisciplinary mediums put the narrative first. As Midwest transplants to the South, we explored the local barbecue, art, and history. Dana lived in a small town near the university which gave them insight into the authentic stories and traditions. Their work has an emotional perspective, one that gives the viewer insight into the trauma and guilt we often carry throughout our histories. Dana brings these ideas together in a poignant photographic exploration.

Dana Smessaert is a photographer and writer who explores history, change, and melancholy themes in their work. Receiving their MFA at East Carolina University in Photography. They are an Adjunct Instructor at Herron School of Art and Design, Grand Canyon University, and Mount Olive University. Dana is on the Pride Caucus Leadership team for the Society of Photographic Education for the second year, working as a reviewer and mentor. They enjoy practicing yoga, hiking, and reading in their free time. Dana will be working on their latest project, a photo book titled Uncommon Sense, in Europe this summer.

Follow Dana’s work on Instagram at: @_damnitdana

An Obligation to do One’s Best

What I hold above all else is an innate sense of justice. Through art, there is a way to bridge the harsh realities people face today, to be seen and reflected while giving back beauty and hope. Through my writing and visual art, I draw deeply on my experiences in the world and the stories of the many people I have met along the way—a blend of myth and reality.

I am a collector of knowledge first in my practice, brought on by my early schooling in Anthropology. My process begins in a passive stance, usually by going for walks. To visually start to understand the place I am situated. The act of being still in this early stage is accompanied by reading. This can be anything from Sci-Fi and high fantasy to theory. I am inspired by classic literature, like Faulkner, Poe, and Willa Cather. These authors allow a look into a past culture through the lens of reality, demise, and hope. As an artist, I am looking at how to pivot a conversation into an action. This, however, can not be possible without fiction.

There must be room for imagination and wonder that anything can be. I find these inspirations in the work of Bas Jan Ader, Gordon Matta-Clark, and Anges Denes. Who challenge what seems to be immovable spaces. These works hold a visual weight that allows art to create a sense of wonder in anyone who witnesses. They call forward questions that don’t require theory or academic elitism. This is the foundation of my art practice. As a queer artist, I dream of a world where the American dream is dead. There is violence constantly around us in the United States. I pull gesture, beauty, time, and rage from the works of Maya Deren, Claude Cahun, Ana Mendieta, and Bill Viola. I look to these artists’ ability to shape and hold time still, to leave space for the truth of who humans are—seizing and destroying the confines we have accepted as our culture. Using these tactics of voyeurism and research, I create these liminal spaces of wonder. Offering a space outside violence, the American dream, and elitism. To ask, but what if?

Epiphany Knedler: How did your project come about?

Dana Smessaert: For me, projects always come in through the backdoor, and they make a coffee and sit at the kitchen table making themselves at home, and then, like a week or month later, I am like, “Oh, Hello!” As much as I think I can actively plan projects from A to B, it’s all nuanced. Which took me a while to realize was okay, especially in an academic setting like An Obligation to Do One’s Best, my MFA work. This piece started with my writing first, which always has weaved in between personal experiences and theory and through reading. I was reading some classic literature to help me understand my environment and the American South’s history during that time. I had felt very alone then. I was going through significant self-actualization regarding my gender and sexuality.

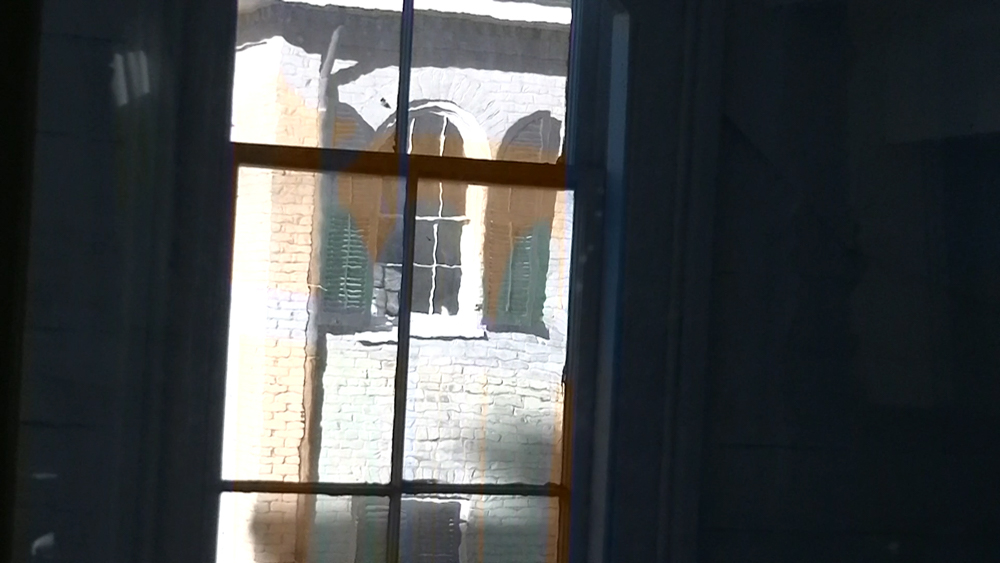

I lived in Farmville, North Carolina when the work was done. In retrospect, I hold that town close to my heart. However, I felt isolated and watched at the time—the awareness of my whiteness and perceived gender was intense. I started to unpack my preconceived notions of the South, filled with harsh stereotypes of racism, the hillbillys (Deliverance), and the backward culture that the North perpetuates.

To say the first year there was a culture shock is an understatement. The longer I lived there, the more I started to understand how community-driven the space is and how these larger narratives of the collective history of Black and White Southerners are so different from what history the North is taught. W.E.B. DuBois talks about the veil of the mason-dixon and that wholeheartedly still exists. The thing about the South is there is a reality and a myth, and people live between those spaces. The mythos of the southern hospitality, how the antebellum era is portrayed, and a loyalty to the Land. Where the realities are the deep poverty, towns still hold that segregation line ideology, even if it’s not a legal law and an underlying sense of caution to outsiders. I had heard from the community’s Black and White elders that the issue wasn’t about race. It was about class. That class was the issue at hand. So, I began to realize that what I was exploring was trying to figure out how I fit in this town and how to celebrate the myth of the South while not negating the reality.

EK: What relationship does place or location play within your practice?

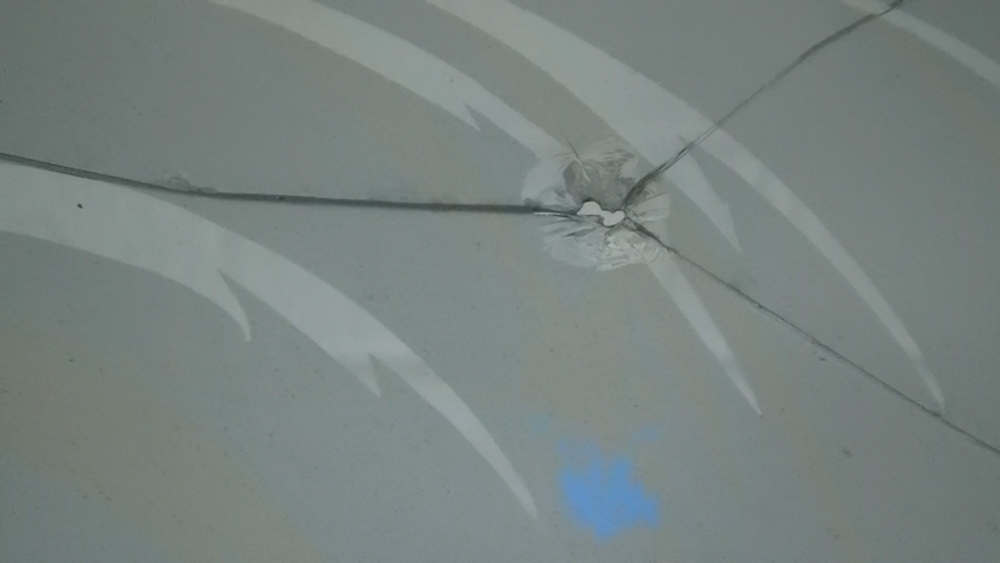

DS: Place and the history of place have always been a part of my life. Growing up in Mishawaka, Indiana, my dad’s family takes great pride in the history of the town’s Belgian neighborhood on the west side. Where they grew up as third-generation kids, this kind of loyalty to a place’s history is something I don’t see so much anymore, especially in far-removed white European immigrants—this lack of genuine culture outside of material things and religion. In my practice, this theme has been resurfacing a lot. I am moving away from thinking of place as only a human-defining space and giving more agency to the Land as an entity that has shaped humans. It’s still a bit clunky in how I talk about it, but the images in this work are where I first started to explore this idea. The reciprocity failure lends the images a suspended belief, a limbo, a space to contemplate ideas of control and Land. I think I’m still figuring out my relationship with the Land, which is, at this point, what any Non-indigenous person here should be thinking about if we use it so specifically in our practice. This project was my touchstone for deconstructing and reconstructing my relationships with my surroundings as an outsider. This, above all, has become a theme in my work.

EK: Who or what was the inspiration for this project?

DS: This is a tricky question because of all the different pieces that make up the work. The best blanket statement was my frustration. My frustration with the answers I was given to what I was seeing, being told that I was reading into things, and just feeling isolated in my thinking. I was digesting a lot of emotions in my work, and right now, the art world is at a weird point in the academic setting, where art is being quantified to make it more valid next to the sciences. I would be seeing points of how racism was built into the small gestures, the architecture, and also the more obvious fashion. Whenever I brought this up, it was kind of dismissed, like a class issue. It’s not that bad. It is what it is. It was that statement. It is what it is, something I’ve heard my whole life to rationalize things away.

I was so angry, honestly, because these things were to me so in your face. This is also the pre-George Floyd era when we had these conversations.

Looking back at it now, it’s kinda funny how nuanced the work ended up being. There were more in-your-face versions of it at times. One version of the piece was to hang only the images but with glass frames with like stunt-level blood capsules inside them. I wanted it to be a show opening, and would I walk in, very Ppipilotti Rist style, and bash the glass with a Louisville Slugger. Bloodying the landscapes.

But what pulled it back is the quote that is the title of the installation, An Obligation to Do One’s Best; it’s a Willa Cather quote from The Song of the Lark. The full quote is, “He used to say that he never felt the hardness of the human struggle or the sadness of history as he felt it among those ruins. He used to say, too, that it made one feel an obligation to do one’s best.” I still think that is the best summary of the work, especially when standing in the middle of the installation. Maybe that quote is even the best summary of my work overall. Ultimately, I didn’t want the anger to be at the forefront.

EK: Can you talk about your interest in photography and installation?

DS: I struggle with photography sometimes. It’s a love-hate, and installation helps bridge photography’s shortcomings for me. I respect and love straight photography and am working my way back into loving it again just for myself, not necessarily in my professional art practice. I have this war between being a die-hard film freak and loving the immediacy of digital – but I hate how clunky the cameras are; they are an ick for me. I fell in love with installation as an undergrad. I loved the possibility of having a visceral experience with all the senses engaged. This came from all the interactive live-scale history set museums I visited as a kid. I love being transported. Which I think is why photography and installation mesh so well: photographs transport time in a way that you can be tricked into thinking its objective. Of course, it never is, but that illusion is unique to the medium. I also enjoy how installation has no wrong way to interact with it. In many cases, the viewer can walk in and never see the work from the same angle as the person next to them. I find that beautiful and also accessible.

EK: What’s next for you?

DS: I have started a new project that I am calling Uncommon Sense right now. These last three years, I have been processing a hard loss in my life and coping with that grief. While the work isn’t explicitly about that experience, I want it to weave between grief, Land, and the existential dilemma that is happening right now for many younger people in the world. The book The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros, Greece, the American South, and the color blue are big inspirations for this project. It’s still in its infancy, so I am excited to see who’s drinking coffee in my kitchen this time.

The best way to stay updated with new projects is to follow me on Instagram. I have been playing around with the idea of creating content for YouTube as well, so stay tuned.

Professionally, I encourage everyone to investigate MidwestNice Art Collective. I recently juried a show for them. They are doing fantastic work and always looking for entries to their shows. Lastly, the Pride Caucus of SPE will host portfolio reviews for LGBTQIA2S+ artists to receive feedback from artists in that community—from student to graduate and professional reviews. Please check out the Pride Caucus Instagram for more information on those dates.

Epiphany Knedler is an imagemaker sharing stories of American life. Using Midwestern aesthetics, she creates images and installations exploring histories. She is based in Aberdeen, South Dakota serving as a Lecturer of Art and freelance writer. Her work has been exhibited with Lenscratch, Dek Unu Arts, F-Stop Magazine, and Photolucida Critical Mass. She is the co-founder of MidwestNice Art.

Follow Epiphany Knedler on Instagram: @epiphanysk

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anna Guseva: The Black Night Calls My NameJanuary 26th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Jake Corcoran in Conversation With Douglas BreaultAugust 10th, 2025

-

Matthew Cronin: DwellingApril 9th, 2025

-

Jordan Gale: Long Distance DrunkFebruary 13th, 2025