Joe Reynolds in Conversation with Douglas Breault

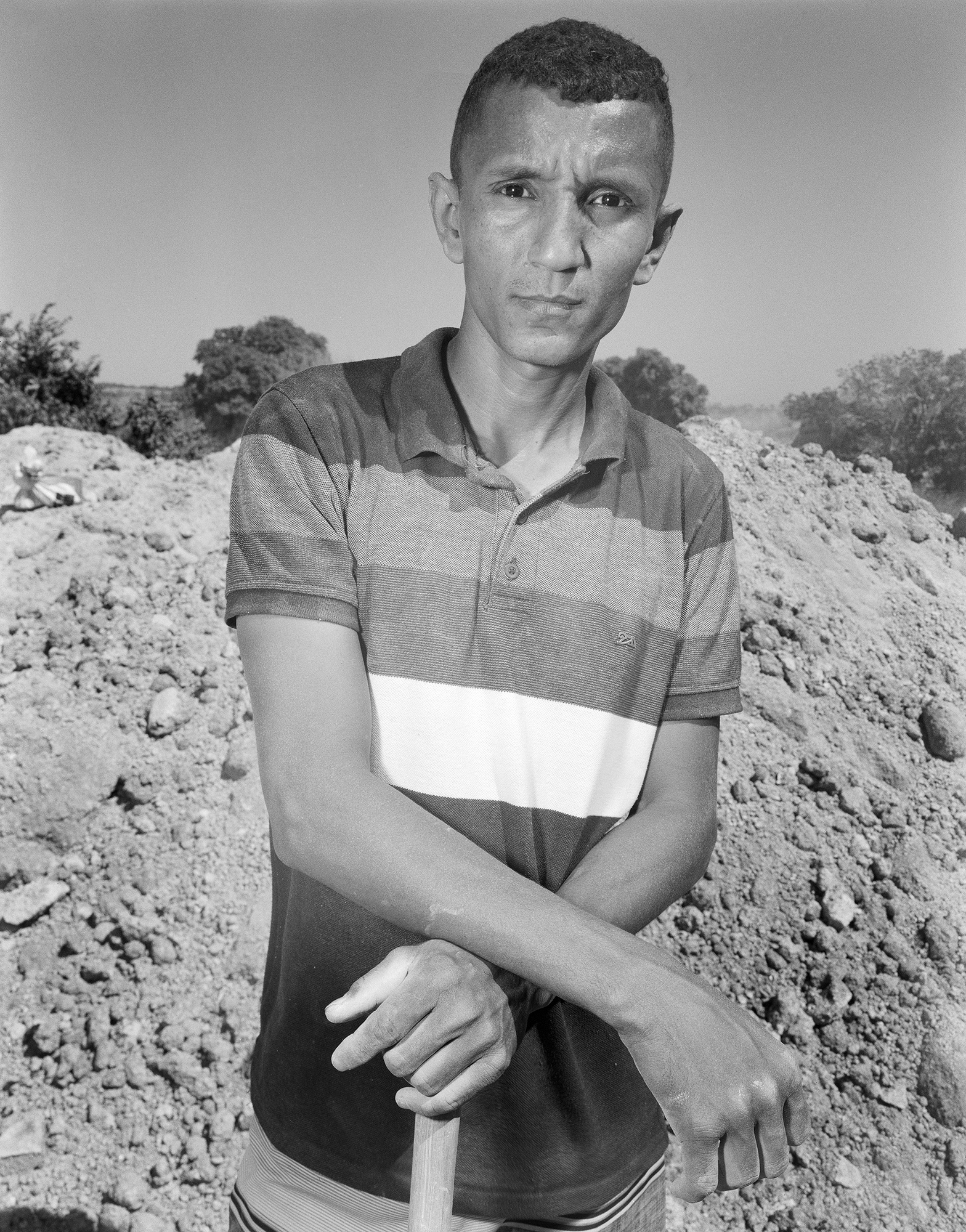

Joe Reynolds uses a large-format camera to build bonds that stretch across continents. While geographically from the American South, his bloodline connects him to the people of Brazil. These origins converge in the series Cristalândia, a photographic exploration of a Brazilian mining town, where he introduces himself to the community in search of camaraderie through shared human experiences. Reynolds seeks to resolve the disjointed feeling of being Brazilian in America and American in Brazil. His images evoke a curiosity and trustworthiness distinctly different from that of a tourist. The black-and-white photographs avoid lush depictions of tropical paradise, yet they still employ elements of beauty and celestial light to offer a sincere appreciation of a community.

The photographs in the series often position the viewer close to the ground, inviting them to sit in the spaces and feel steady within the frame. One image of an elderly woman seated outside highlights the beauty of her aged skin as she seemingly turns inward in recollection. Her exact identity is unclear, but her stature as a matriarchal figure who carries the history of her community on her surface is admired within her composition of the frame. Another photograph, featuring crochet materials perched on a leather sofa, similarly situates the viewer in a seat that warmly tells the history of the room. Reynolds’ photographs are remarkable for their stillness — a gentle introduction and attentive study of the relationship between the land and its inhabitants.

What does it feel like to photograph Brazil from your perspective as an American?

I remember as a kid I would always get excited at the Miami airport because that was the first airport in our 4-legged trip where I’d be submersed in people from around the world (Atlanta was much smaller in the 70s). And when we boarded the plane to Rio, the sound of everyone speaking Portuguese was comforting. Like many people raised in bilingual households, I feel I have two personalities, and to me my Portuguese-speaking personality is much warmer. I’m sure the warmth of these family trips still colors my impression of Brazilian culture and how I interact within it. But Brazilians themselves use the term “calorzinho” (little heat) to describe how they interact with each other, because human warmth permeates their interaction. So I always lead with “calorzinho” when I meet another Brazilian, even if my vocabulary and awkward gestures eventually betray my foreignness. My shyness was debilitating as a kid, especially in Brazil where I was terrified that people would discover I was different. So this project began as a determination to participate the way my heart always wanted to. Photographing Brazilians was a way for me to wear my awkwardness out in the open where it was clear that my camera made me weird. I could deflect my weirdness onto my camera, temporarily. After that, the “calorzinho” took over and allowed me to gently reveal my deeper weirdnesses to them and, surprisingly, theirs to me. Brazilian vs American melted away, and I just saw my childhood reflected in their world, São Paulo and Chattanooga blended into one childhood. I still experience culture shock, but when it’s safe to be weird, curiosity can overcome the shock.

What strikes me the most about Cristalândia is the direct connection that this community has with the land and how fluidly that land becomes a part of them and them to it. I think a relationship with the land is a crucial part of place, but it takes stepping out of our air conditioned cars to sense the forces that shape that land and ultimately us. Technology has altered life there no differently than anywhere else. But even as people spend more time on their smartphones behind taller security walls, a bicycle is still more practical than a car and face-to-face more effective than a text. It’s personal experience that shapes their understanding of a location, and you don’t need a plaque to explain it. Nor could it. You can see the evidence of their personal experience with place, if you walk slowly enough.

What do you look for when making your images?

Broadly speaking, I’m looking for any place where forces are acting upon each other, whether nature & man, nature & nature, or man & man. But I try to avoid being too concious of that, and I usually just look for new ways to organize three-dimensional space within a two-dimensional rectangle. I’ve chosen my camera and lens because it’s slow and emphasizes the foreground, forcing me to get close to things — the antithesis of pararazzi. My challenge is to keep this space from warping so that it’s still relatable. My goal is always to find a person to photograph because that’s what scares me the most and consequently what will teach me the most. But they’re hard to find, so I usually just wander around with no destination, photographing whatever I find. I trespass with curiosity, which means that I’m intentionally moving into private spaces. I might walk into your yard in hopes that you come out and ask, “What are you doing?”, which is my chance to start a relationship with you and tell you exactly what I’ve found in your yard that interests me. But I have to genuinely be curious about it, because people know when you’re faking, and then they close up. But if they see you’re genuinely curious, they slowly allow you into their private spaces. So my challenge is just to be curious about where ever I find myself. The view camera helps build this relationship in that it requires a longer exposure, and it’s hard to hold an expression for 10 seconds. In that time, the public veneer softens, hinting at the vulnerability that lies below, an essential ingredient to relationship. Since there are no film processing labs in the area, neither of us can see the picture till much later, so the measure of success is not the picture but whether we had a good relationship in making it together.

Where do you draw inspiration from?

For this project, Carlton Watkins, Eugene Atget, Mark Steinmetz, Nick Nixon and Judith Joy Ross are always on my mind, and Vic Muniz’s “Wasteland” has been an inspiration from the beginning. This past year, I’ve been studying how, historically, Brazil has othered themselves through photographs. So I’ve been tracking down the work of Mario de Andrade, Silvino Santos, Marc Ferrez and painter Alfredo Volpi. On a daily basis, though, I try not to look at photographs but everything else instead…. Marie Howe, Rilke, Mr. Rogers, The Little Prince, Ocean Vuong, Padraig O’ Tuama, Michael Longley, Anthony Appiah, Bach, Schubert. In particular, I relate to Andy Goldsworthy’s efforts to make visible the invisible forces that shape our lives, to the extent that his works are merely a catalyst and soon disappear back into the cycle in which we live. “The real work is the change,” he says. As hard as I work to haul my equipment on planes and buses and to carry it around town, my real work is the change that happens between my subject and me in the 20 minutes of our conversation and in the 10 seconds of the exposure. The real work is the relationship.

Joe Reynolds is a photographer, teacher and writer based in Lawrenceburg, TN. His work relies on the collaborative nature of the large format camera to build relationships with the land and people he photographs. His pictures describe bonds formed from shared experience, bonds which weave us more deeply into each other than labels of nation, creed, race or gender. Since 2008, he has been photographing his evolving relationship with the small, crystal-mining town of Cristalândia, Brazil. As a dual Brazilian/American citizen, he explores his growing sense of belonging in a community with which, at first, he shared nothing beyond Brazilian citizenship.

His work has been supported by two Fulbright grants, a Tennessee Arts Commission fellowship, residency at Anderson Ranch Arts Center and a Seebacher Prize for Fine Arts. In November, he will share his work at CENTER’s Review Santa Fe, followed by a residency at Light Work in August 2025.

Douglas Breault is an interdisciplinary artist who overlaps elements of photography, painting, sculpture, and video to merge spaces both real and imagined. His work has been collected, published, and exhibited nationally and internationally, including at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the Czong Institute for Contemporary Art (South Korea), Space Place Gallery (Russia), the Bristol Art Museum, the Rochester Museum of Fine Arts, Amos Eno Gallery, and VSOP Projects. Breault has been an artist in residence at MassMoca and AS220 and was awarded the Montague Travel Grant to study in London and Paris in 2017. Douglas is a professor of art at Babson College and Bridgewater State University, and he has been a guest critic at MassArt, Wellesley College, Kansas City Art Institute, and the Slade College of Art, among others. Douglas is the Exhibitions Director at Gallery 263 in Cambridge, MA. He received his MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University and a BA in Studio Art from Bridgewater State University, and he currently divides his time between Boston, MA, and Providence, RI.

Follow Douglas Breault on Instagram: @dug_bro

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026