Rehab Eldalil: The Longing of the Stranger Whose Path Has Been Broken

©Rehab Eldalil, Yasmine (32) picks wild herbs as she walks through the valley near her home at Sheikh Awad village. February 2021. Yasmine was six months pregnant, walking the village herd around the mountains of Gharba, when we first met nearly seven years ago.

Some years ago, I had the very good fortune to spend time exploring the rugged and vast mountainous expanse of the Sinai Peninsula and the Bedouin communities that were scattered throughout. One of those communities, the Jebeleya tribe of St. Catherine, is the focus of this intriguing visual exploration of a search for one’s origins in an historic nomadic culture facing challenges and transitions. The documentary photographer and Bedouin civil rights activist, Rehab Eldalil, employs a multi-layered approach in fashioning powerful portraits of individuals, a tribe, an ethnic community in the midst of a stark landscape in her project and book, The Longing of the Stranger Whose Path Has Been Broken, published by FotoEvidence. She manages this feat with input from all sources and with varying original visual methods that charm the observer while providing a voice for her subjects. Thus, women from the Bedouin tribe use embroidery within a photograph to convey the extent to which they want their identities revealed; portraits are often depicted as flashes of brilliant-colored robed figures climbing rugged rocky hills in stunning contrast; and local herbs are identified in silky transparent parchment that tends to contradict the thorny nature of the particular plant. The Bedouin community of the Sinai Peninsula is being buffeted by various forces which are provoking unwanted changes. The imposition of arbitrary housing by the Egyptian government has provoked strenuous opposition. Also, the influx of new roads and tourist hotel developments due to the draw of the historic St. Catherine’s Monastery perched above the village has disrupted the tranquility of the valley. Eldalil makes every effort to capture and document the life of the tribe prior to the onset of what the future might bring. This is a longing glance at the beauty of what once was in hopes that it might still emerge triumphant.

©Rehab Eldalil, The city centre of St. Catherine protectorate in South Sinai, Egypt. Naturally isolated from other regions in Egypt and uniquely defined by the interconnectedness of people and land. January 2021.

According to Eldalil, the book “… is a personal project in which I reconnect to my indigenous Bedouin ancestry by collaborating with the existing Bedouin community in Sinai, Egypt over a span of 10 years to explore the notion of belonging and the interconnectedness between people and land that shapes this notion.

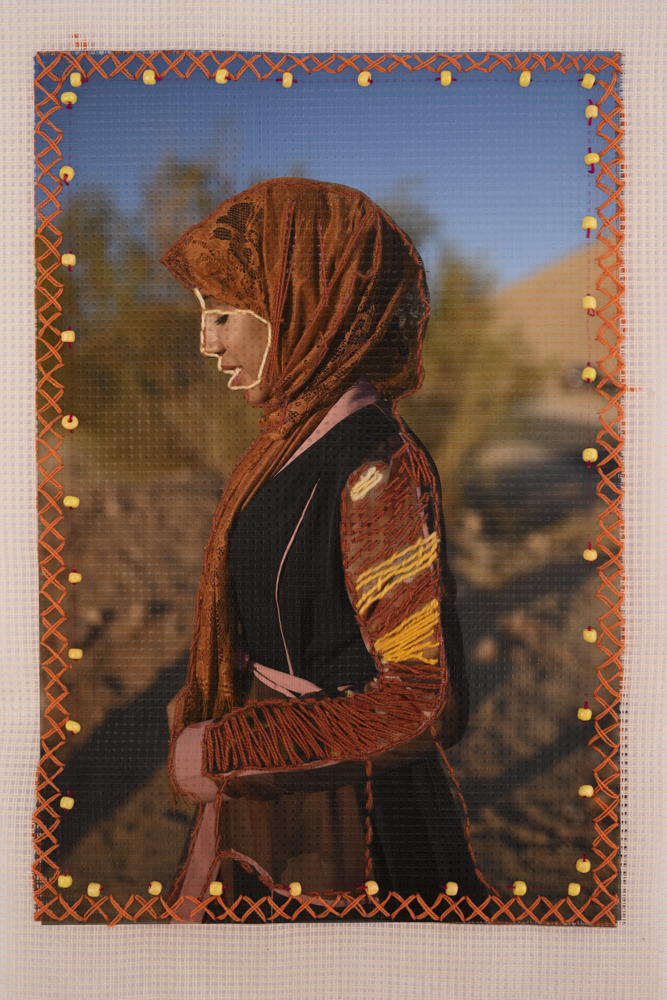

©Rehab Eldalil, Up until the 1990’s women were prohibited from being seen by men from other tribes without consent. As the technology evolved, the awareness of the circulation of an image on social media and lack of control of who gets access to an image escalated this concern, leading some women from never being photographed in fear of uncontrolling its access, circulation and how they’re represented. Collaboratively working with the female Bedouins, every woman I photograph adds embroidery on to her portrait printed on fabric. She has the freedom to reveal or conceal using the traditional medium of embroidery. Taking full control over her representation in the project. Embroidered photograph of Nadia (20) by her and her cousin Mariam (19) from AlTarfa village.

The community are participants in the creative process, they’ve contributed with their traditional mediums such embroidery, poetry, storytelling and plant foraging. The result is a dance, a visual conversation on the continuous human process of searching for home and a celebration of the indigenous experience that has long been seen through a romanticized gaze. The final outcome of the project is a complementary collection of photographs, written content, embroidered photographs on fabric and photographic paper, artifacts, sound and video.

The book is universal as much as it is personal, it essentially questions what it means to belong, what is this indescribable connection to the land that we all long for and the indigenous experience that is filled with both sorrow and celebration. It invites readers to examine their own idea of belonging while acknowledging the community’s voice, consent and collaboration in the process.”

©Rehab Eldalil, Expensive in material – less traditional garments and jewellery are made as the local economy declines leading women to wear generic clothing items imported by vendors from other cities in Egypt. Nevertheless, traditions evolve and stay alive: women, specifically brides-to-be, make fashion statements by wearing garments gifted to them by their husbands to be; a sort of subtle flirtation as she walks everyday into the mountains. As told by Hajja Rabia’a. Embroidered photograph by Fatma Om Gawaher from AlTarfa village

Rehab Eldalil is an award-winning documentary photographer, visual storyteller and educator. Her work focuses on the broad theme of identity explored through participatory creative practices. She received her photography BA from Helwan University, Cairo in 2011, photography MA from Falmouth University, UK in 2020 and a certificate in documentary photography from the International Center of

Photography, New York, USA in 2021. In addition to developing personal projects, she works with NGOs and publications documenting human interest stories in North Africa and Middle East regions. In 2013, Rehab began her research on collaborative lens-based approaches and representation in visual storytelling. Her long-term project The Longing Of The Stranger Whose Path Has Been Broken was shortlisted for PHmuseum Women Grant 2021, 6 Mois Photojournalism award 2021, Philip Jones awards 2021, Marilyn Stafford award 2021 and Catchlight fellowship 2020. She was awarded AFAC & Magnum Foundation’s Arab Documentary Photography Program grant 2020, National Geographic Society’s Emergency grant for Journalists 2020 and Creative Activism award 2021. Rehab was awarded the FotoEvidence W Award 2022 to publish her project in a book form, she won the World Press Photo Regional Award 2022 and received the Trobades Premi Mediterrani Albert Camus award 2022. Most recently, she received the Women Photograph and Getty Images Inclusion grant to work on her new project Nesting Birds. Rehab’s work has been exhibited in many exhibitions around the world including Egypt, USA, UK, Germany, Brazil, Switzerland, The Netherlands, Canada and Greece. Her book is available for sale worldwide.

©Rehab Eldalil, Hoda (23) from St. Catherine city stands on the edge of a hill looking over Gharba Valley. April 2019.

©Rehab Eldalil, Moussa Algebaly (25) from the Jebeleya tribe lies under the tea flower plant after daily maintenance in his garden in Al Tarfa, South Sinai, Egypt. April 2020. When boiled, the tea flower plant helps reduce period and labour pain for the Bedouin women who struggle to find medical care. After years of drought, a major flood occurred in mid-March 2020, providing an agricultural opportunity for the Bedouin community amid the economic impacts caused by the pandemic. For the community whose main source of income is tourism, the flood is a miracle. The land has given back to its keepers in the time of crisis.

©Rehab Eldalil, Embroidered photograph of Mahmoud in his home in AlTarfa village. Embroidery by his cousin Nora from AlTarfa village.

©Rehab Eldalil, “We’re almost there” -A Bedou’ white lie to get you to the top of the mountain. The Milkyway appears on top of Sheikh Awad village which only gets electricity for 5 hours a day. Stars has long been the Bedou’ guide through the desert.

©Rehab Eldalil, Mohamed Ghoniem (12) adjusts his scarf as he waits for his turn at the community clinic. Gharba Valley, St. Catherine, South Sinai, Egypt. March 2020.

©Rehab Eldalil, Every day, the women of AlTarfa village walk in a group of four from sunrise to sunset leading the herd of sheep and goats as they feed on the wild plants of the surrounding mountains. As the herd feeds, the women talk, share concerns, ask for advice and learn from one another. A sisterhood that is formed through mutual support and unity. From left to right: Nora, Nadia and Mariam stand on the edge of a mountain looking over their village AlTarfa, St. Catherine, South Sinai, Egypt. February 2021.

©Rehab Eldalil, Embroidered photograph of Jabal AlBanat, The Mountain Of The Girls. Embroidery by Yasmine (32) from Sheikh Awad village. Legend tells of three beautiful Bedouin girls; the prettiest among the tribe with the longest most luscious hair of all. The girls’ parents forcefully arranged marriages for them all on the same night. Feeling forced to wed; the three girls decided to go up a nearby mountain. Bonded by their long strong hair braids; together the three girls leaped off the summit. Since then the mountain has been named after them as a reminder for women’s right to choose – Jabal Albanat: The mountain of the girls.

©Rehab Eldalil, Zeinab (27) walks back to AlTarfa village with Salema (42), Aysha (41) and Amal (45) after a day’s walk across the mountains to feed the village herd and collect medicinal herbs for the community. Medicinal herbs have become more important this year to increase the immune system against Covid due to the lack of medicine and medical aid for the Bedouin community. AlTarfa, St. Catherine, South Sinai, Egypt. April 2021.

©Rehab Eldalil, Seliman holds the Khodary plant in his family garden in Gharba Valley, St. Catherine, South Sinai, Egypt. October 2020. Seliman manages an ecolodge with his cousins in Gharba valley but as the pandemic spreads throughout Egypt, less and less guests come to stay at the ecolodge and now the family redirects their focus on the family gardens. “We don’t have Corona here, but we are affected by it. Look, these plants are our face masks.” says Seliman.

©Rehab Eldalil, Father and son walk over the hill to watch the last moments of sunset. The role of the father within the family dynamic in the Bedouin community does not only comprise of providing food for the family. Fathers care for their children when the mothers are off walking the village herd. As the mother walks for hours into the mountains, fathers are staying at home or working from home to care for the children. Gharba Valley, St. Catherine, South Sinai, Egypt. December 2018.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

From Here to the Horizon: Photographs in Honor of Barry LopezApril 3rd, 2024

-

Shinichiro Nagasawa: The Bonin IslandersApril 2nd, 2024

-

Kristine Nyborg: Learning to Speak BearApril 1st, 2024