Photographers on Photographers: Ben Marcin on Adam Davies

Adam Davies

Adam Davies is an exciting, young photographer relatively new to Baltimore, a resident artist at the Creative Alliance, East Baltimore’s legendary art space and incubator of regional art talent. Unlike most photographers working today, Adam has largely eschewed the digital revolution that has exploded across the photography scene and opts instead to work with a very large 8×10” metal view camera. The results are pictures that transcend normal viewing conventions.

As so often happens when two photographers meet, ideas and techniques are exchanged and evaluated. Even when one has been working in this field for a very long time there is always something new to discover and there is no better way to find this out than in the presence of an excellent photographer.

I first saw Adam’s photographs in a large, pitch black room on the ground floor of the Creative Alliance. Unfortunately, I had been out of town and missed the opening reception for his solo show, Reroutings, but Adam invited me over for a personal tour. The main gallery was cordoned off from the rest of the building’s interior by an immense black curtain that Adam had installed. The gallery was rendered completely dark except for carefully positioned spotlights pointed at each 56×70” picture. This gave them the eerie effect of being backlit and floating in mid-air. It took a minute or so for my eyes to adjust but slowly each image locked into view. I knew going in that Adam used an 8×10” inch view camera so I was expecting to be impressed, but not quite like this.

Installation photographs, Creative Alliance, Baltimore. March – April 2018. ©Ryan Stevenson

As I looked at Adam’s enormous and beautiful photographs of highway bridges and urban forests, I noticed that it became difficult to not keep looking. Almost every picture included some form of graffiti set in an unusual context. The photographs, while seemingly quiet and elegant in mood, contained discrete sections that continually invited further exploration. For example, in “Bloomfield Bridge, Pittsburgh,” my attention was directed immediately to the brightly colored paintball splatters adorning the bridge support. After pondering why and how they got there, my gaze slowly wandered over to the huts or shacks beneath the bridge on the left. Then up towards what looked like a hospital complex in the distance. Then to the right where another section of the same (or different?) neighborhood continued. The bridge support facilitated a very interesting division of the picture into separate, breathing spaces, each one in perfect focus and tone. As a working photographer, I looked at “Bloomfield Bridge” and understood that the only way to make a truly great photograph like this was to use a film view camera. Anything less and the magic would disappear. There was also something else that I saw in Adam’s photographs: a certain depth to his prints that can only be attained by a very high attention to craft.

Opening with Los Angles-based musician Alex Zhang Hungtai (of Dirty Beaches & Last Lizard) & Performance by Baltimore-based percussionist Adam Rosenblatt

I myself have been shooting with digital cameras for the past eight or nine years. Prior to that, I had been a film photographer. I’d built my own Cibachrome darkroom and stayed with film long after many of my colleagues had moved on to digital. When the math inside the top digital cameras got to a certain point I also made the switch. There were no regrets. Using a digital camera was extremely liberating. I could stitch a dozen or more photographs together and make hyper-resolution images. Using my smartphone, I discovered I could make huge abstract composites. I found myself making images that would have been impossible with my old 4×5” view camera. However, for some time I had been considering returning to film for certain kinds of work – particularly those involving landscapes – and now, looking at Adam’s photographs, I saw the possibilities. I mentioned this to Adam and, much to my surprise, he offered to walk me through his workflow for creating prints from color negatives. We would even work on my own negatives. At first, I was hesitant about this not wanting to waste a lot of Adam’s time. Also, there would certainly be dozens of youtube videos I could pore through to figure it out. Adam simply said, forget about youtube, I will show you how to do it properly. And, just like that, I went through the open door.

Ben Marcin was born in Augsburg, Germany. Many of his earlier photographic essays explored the idea of home and the passing of time. “Last House Standing” and “The Camps” received wide press both nationally and abroad (The Paris Review, iGnant, Huffington Post, Slate, Wired Magazine). More recently, he began exploring the myriad structures of the urban core in Towers, Street, Stairwells and Museums. His photographs have been shown at a number of national galleries and venues including the Baltimore Museum of Art; the Delaware Art Museum; The Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester, MA; The Center for Fine Art Photography in Ft. Collins, CO; The Photographic Resource Center in Boston; and the Houston Center for Photography. He is currently represented by the C. Grimaldis Gallery in Baltimore, MD.

Adam Davies received an EdM from Harvard University (2001) and an MFA from Carnegie Mellon University (2005). Davies is a recipient of grants from the Vira Heinz Endowment, the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, and has held residencies at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, the Fine Arts Work Center (FAWC) in Provincetown, and Yaddo in Saratoga Springs. He previously has taught at Carnegie Mellon, Catholic, Robert Morris, and Harvard Universities in addition to workshops at the FAWC and Creative Alliance, Baltimore. His photographs are held in a number of private and public collections including the DC Art Bank, Georgetown University, Howard Bank, Fidelity Corporate Collection, and the Washingtonia Collection.

Davies was honored as Outstanding Emerging Artist at the DC 30th Annual Mayor’s Arts Awards and is the recipient of the 2015 Clarence John Laughlin Award. He is currently an artist in residence at Creative Alliance in Baltimore where his recent solo exhibition in March 2018 featured collaborations with sound artists including the Los Angles-based musician Alex Zhang Hungtai and the Baltimore-based percussionist Adam Rosenblatt. He is currently working with the award-winning author Joan Wickersham on a project based upon the Swedish seventeenth century shipwreck, ‘Vasa.’ In October 2018 he will present his ongoing photographic series, ‘Reroutings,’ at the Midatlantic TED Talk in Washington, DC.

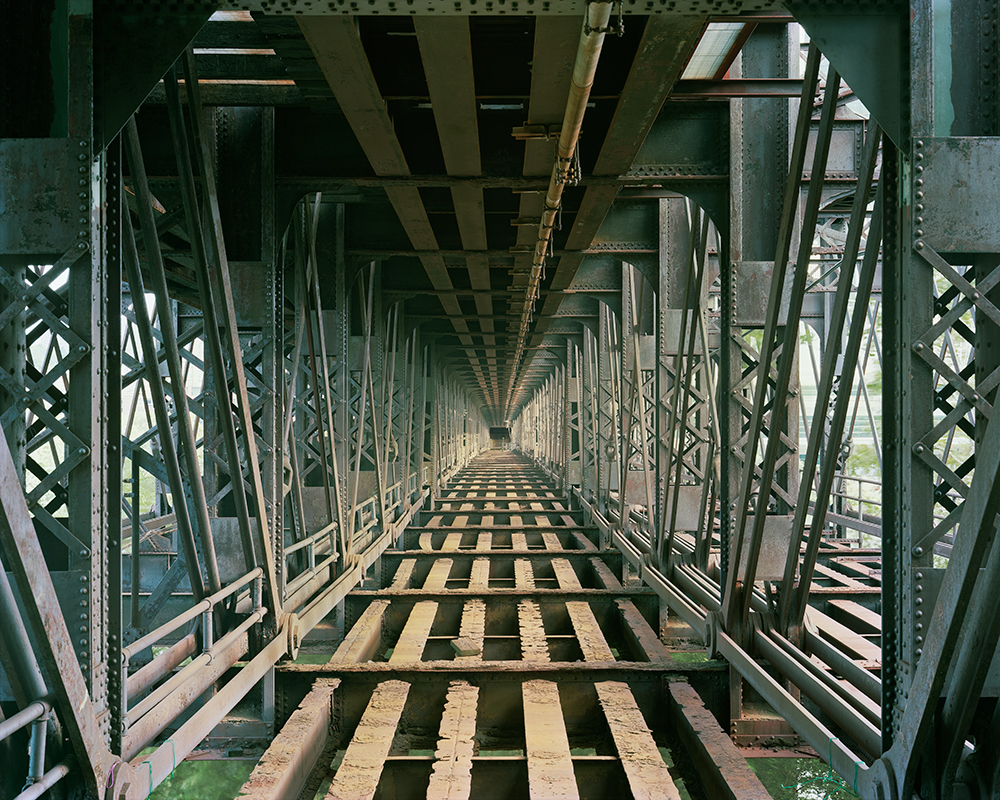

Interstate 68, Maryland, 2017 ©Adam Davies

Ben Marcin: Remind me – how did we meet?

Adam Davies: I first became aware of your work in 2016 when I moved to Baltimore. I saw a photo from your series Last House Standing at the Baltimore Museum of Art. But we only actually met last year, through Jonathan Blaustein, a photographer and writer who knew both of our work. I was excited to connect as it seemed like we had a lot of overlapping interests.

Under Interstate 476, Philadelphia [Smiling tree], 2016 ©Adam Davies

BM: You shoot exclusively with an 8×10” view camera. It weighs a ton. In addition to all the gear that comes with it, you also carry a metal ladder into the field and you don’t use any assistants. You ship your sheets of film half way across the country to have the keepers drum-scanned. Not many photographers work like that today.

AD: It is a crazy process but it works for me! I find the 8×10” view camera very different from most other cameras out there, either digital or film. It is a beautifully simple mechanical machine, it lets you compose and construct photographs in ways that other cameras don’t. By moving the lens and the back of the camera separately from each other, I can optically manipulate both the perspective and angle of focus within the image.

The process of composing and making a single photograph can last between several hours and several days. So it forces me to work slowly and think about my images and how I get to a site. I prefer working alone because I don’t like to feel rushed or distracted when on location.

I love the quality of film, its look and grain structure. The color negatives have a unique level of resolution and subtlety of color that lets me work at a scale where the highly-detailed photos become immersive to the viewer — I make prints as large as 56×70” in size.

BM: How did you get to this point in your career? Who were your teachers and influences?

AD: I discovered photography in my first year of college. I had a great teacher, Roswell Angier, who basically let me live in the darkroom for the rest of my time as an undergrad. Roswell was a street photographer (his work primarily dealt with people’s interactions in public spaces), but he instilled in me the idea that a camera gives you a license to explore. I was a shy kid but I was fascinated by the architecture and infrastructure of the city, particularly by the discovery of places that were hidden or overlooked. I think early on I just was trying to learn as much as I could about what was going on underground, both literally and figuratively!

A little bit later on, a visiting professor, Michael Collins, was the first to encourage me to try out an 8×10” view camera. It took me a while to figure out how to use it, but I became obsessed. I would borrow the camera from the school (often for weeks at a time because no one else was using it!)

Before college, the idea of being an artist was something I didn’t really understand or think possible — and then as an undergrad I was fortunate to have these amazing, inspirational teachers who really made me feel that a career in the arts was possible. Because of this, I felt it was very important for me to advocate for the role of the arts in society so I applied to Harvard University for an EdM (Masters in Education) in Arts Education focusing on museums, adult education, and public policy. Following that I worked at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) at MIT and did some teaching. But I felt like I was becoming disconnected from making art and made a difficult decision to go back to grad school for my MFA at Carnegie Mellon.

After getting my MFA, I taught at local universities in Pittsburgh for a couple of years. I also managed to get a series of artist residencies that sent me to Wyoming, Virginia, upstate New York, Provincetown, and Marfa, Texas. By the end of these travels, I found myself working at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, first as photographer of the permanent collection and then as a Lecturer and Media Specialist in the Department of Adult Programs where I designed tours, docent training, and new educational programming based around studio practice related to the museum’s collection and special exhibitions. I left the Gallery a few years ago to focus on my own work again and moved to Baltimore in 2016 as an artist-in-residence at Creative Alliance.

Bloomfield Bridge, Pittsburgh [Paintballs], 2017 ©Adam Davies

BM: The first thing I noticed in your apartment was that great big wall of books, mostly about art. I haven’t seen something like that since my dad’s Library of Congress days.

AD: Yes, books are something I am passionate about, reading and art history are big parts of my life.

BM: The second thing I noticed was your analog stereo system – you only play albums. The tie-in to your photographic practice seemed pretty clear to me.

AD: I dig analogue. I like old audio equipment, I collect old film cameras, and I have way too many books. I am sure some of this is sentimental, but I also like the materiality of these things, the way a book, record, or film feels in the hand, the way it takes up space, the way it looks. I am not against the digital world, but I like objects that hold information, I feel we interact with them differently, more personally.

Falls Road, Baltimore [Seven heads], 2018 ©Adam Davies

BM: You couldn’t talk me into getting rid of all my CDs but you worked me pretty hard about returning to film. Why?

AD: I remember when you visited my studio last December and we pulled out an old Fuji 6×9″ “Texas Leica” that I hadn’t used for years. This type of camera made a lot sense for your working process (in fact, I had thought the “Last House Standing” series was shot on film). The Fuji is a large medium-format camera, has a sharp lens, and is indestructible, but it is also small enough to hand-hold and shoot pretty quickly.

Tschiffely Mill Road, Maryland [Ladder], 2018 ©Adam Davies

BM: So my wife, Lynn, bought me a Texas Leica for my birthday and I spent a few months shooting with it. I had used large format 4×5” cameras before but I shot chromes in those days. This time I tried negative film and negatives are quite different. Obviously, you can’t see the image upfront like you can with positive film. When I last worked with negatives, almost thirty years ago, I printed from them by using a darkroom enlarger and Jobo drums. Today, it’s done using scans and Photoshop. After watching me flounder around for a while, you decided to step in on my behalf.

AD: I have a lot of respect for shooting chromes as they are so tricky to expose correctly. Shooting negatives is a lot easier because exposures don’t need to be as precise. But while printing a chrome is pretty straightforward, scanning and digitally printing negatives can be a steep learning curve. I figured that I could help you get started and I was excited that you were getting back into film.

BM: I thought I’d seen just about everything in Photoshop but what you showed me was on a different level completely. I still haven’t found anything comparable to your skill set on the internet or in books. How did you acquire all of that?

AD: It took a long time! I picked up a lot from other photographers. The museum photographers and imaging scientists I worked with at the National Gallery of Art taught me how to color match images. And a couple drum scanning specialists that I corresponded with helped me a lot with using histograms and curves in Photoshop. Photoshop is a lot like working in the darkroom, in that everyone has their own way of working and secret tricks or tips.

Interstate 64, West Virginia [“Fuck U”], 2016 ©Adam Davies

Kelly Avenue, Baltimore [Whitewashed graffiti], 2014 ©Adam Davies

Jones Falls Expressway, Baltimore [Hobo Entrance], 2017 @Adam Davies

BM: Let’s go back to your Reroutings solo show at the Creative Alliance in the spring of 2018. What was the inspiration behind this exhibit and how did you come up with the idea for displaying them the way you did? It was a remarkable show.

AD: Reroutings was my first major solo show in Baltimore. It was an exhibition of ten large-scale images each 56×70” in size, primarily taken in Baltimore and Pittsburgh over the past two years.

Much public infrastructure, particularly in these two cities, is marginalized or neglected. There is a subculture — youth, homeless individuals, drug users, and maintenance workers — that utilizes these spaces and interacts with the architecture, leaving behind traces of human presence in the process.

Upon closer looking, some of the photographs reveal discreet graffiti or signs of vandalism that encourage multiple, often contradictory, interpretive possibilities. How do we read these acts of mark-making? Are they humorous? Anti-authoritarian? Cries for help? The photographs highlight the funny, political, or tragic tensions between the marks, the structures that act as their visual supports, and the surrounding landscapes. This layered triumvirate of language, structure, and setting often subversively hints at a culture that is simultaneously nostalgic and angry, melancholic and wickedly funny.

This exhibition represented a culmination of more than two years of research and development, including custom designed lighting and prints of large-scale photographs of roughly five by six feet. The Creative Alliance’s 2000 sq. foot gallery was transformed into a black box space: it was darkened, the walls were painted black, and spot lights were trained on the individual photographs, giving the impression that they were illuminated from behind. The effect was to create a transformative space within the gallery that encouraged close-looking. Because many of the photographs had been taken locally, this in turn, developed a sense of intimacy and community. Musicians Alex Zhang Hungtai and Adam Rosenblatt performed collaborative works during the exhibition.

BM: So how do you think the guy got up to the underside of that overpass to spray paint “Fuck U”? The fall from there looks to be about a hundred and fifty feet. I’m pretty good at getting into difficult places but I still can’t figure this one out.

AD: The road is wider than the bridge structure, so it wouldn’t be possible to rappel down from the highway. My guess is that someone climbed along the green ledge (under the highway) from one of the two banks. It took some nerve, the ledge is very small and there isn’t much in the way of handholds. That is part of what intrigued me about this site: What compelled someone to write this? Who is it directed to? Another element of this picture for me is its context, the photo was taken in the months before Trump was elected and in a rural area of West Virginia.

Park Avenue, Baltimore [“USERP”], 2018 ©Adam Davies

BM: None of the graffiti pictures in Reroutings are your standard graffiti photographs. It’s clear to me that you wanted to steer clear of the stereotypes associated with graffiti photography.

AD: What fascinates me is how graffiti can change how you relate or understand a structure. It is a deeply personal and unedited voice upon a structure that was designed to be anonymous and utilitarian.

14. McCoy Ferry Bridge, Washington County, Maryland, 2015 ©Adam Davies

BM: Where do you see yourself in one year, five years?

AD: Over this coming year, I would like to be wrapping up the “Reroutings” project. I hope to refine and sequence new and existing work into a focused series of images and text for a book draft for publication. I also have a few other related projects in an early stage that I would like to work on further, including some interesting collaborations.

In five years… hopefully more chances to collaborate with other artists, exhibit more widely and build a sustainable career.

Fort Wayne Bridge, Pittsburgh, 2017 ©Adam Davies

BM: What makes a perfect day for you?

AD: A cloudy, grey day with flat light and little wind.

Dune Road, Long Island [Cloud Bridge], 2014 ©Adam Davies

Under Blue Route, Philadelphia [Reflection], 2015 @Adam Davies

18. E Street SW, Washington DC, 2015 ©Adam Davies

Divide, Fort Davis, Texas, 2009 ©Adam Davies

Water Street, Washington DC, 2012 ©Adam Davies

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026