Thesis Project: Antonia Stoyanovich and Cassandra Klos

©Antonia Stoyanovich, Her Own Rodeo, 2018

The American South and the American West occupy places of mythic proportions in our collective imagination. Our ideas of these places are laden with a complex set of preconceptions informed by their unique qualities and the tall tales we’ve been told about them. The artists presented here, Antonia Stoyanovich and Cassandra Klos, both explore and challenge the cultural identities of these regions in very different ways while offering a commentary on an idea that is intrinsic to both – the nature of truth in representation.

In By No Other Name, Klos employs a subtle lyricism to document her subject’s relationship to the Southern landscape and their search for truth within it with. In contrast, the photographs in Stoyanovich’s Myths + Figments are imbued with a heightened sense of directness, simultaneously challenging the authenticity of the mythic American West while casting doubt on the validity of the medium used to do it. Both engage viewers in a dynamic experience of cultural and visual storytelling.

©Antonia Stoyanovich, Friend of the Horse, 2018

Myths + Figments

Boundaries are twisted, and what is believable and what is real in my practice is always in question. Using image based media I create work that expands a mythology of the American West into a contemporary and physical content that viewers can grapple with. From my background in photography I have an understanding of capturing, transformation and reconditioning of a moment. Utilizing image through photography, video, sculpture, and installation I manipulate truth and assume myth as a way of generating content. This relationship has become especially relevant as we all witness the outpouring of fabrication in the media today. What is believable whether it’s real, myth, artifact, or art is what fascinates me.

Raised in the American west, the place has always taken mythical proportions in my mind. Through my relationship of growing from girl to woman in this part of the country I imagine how different motifs of the fictionalized “west” sometimes fit into a contemporary context haphazardly. A stark contrast to a historically hyper masculine view of the American west, my work utilizes beauty and fragile moments to associate itself in the history of photography as well as romanization of gesture and poetics. A collection of figments, from a three legged horse existing, to conjoined white doves or native beauty pageant winners. It is not so much proving the myth exists but the echo that the west’s mythology is constantly created through fresh eyes and seen as much as it is believed. –Antonia Stoyanovich

©Antonia Stoyanovich, Dance, 2020

Kellye Eisworth: In this time of social-distancing and greater isolation, how have you adapted your studio practice to the current situation, and and how is it impacting the work you’re making now?

Antonia Stoyanovich: My studio practice has always considered relationships, originally between characters and the camera but now I find myself considering the archive and our relationship as photographers to image collecting. What’s the implied relationship of one photograph to another? How do we collect images? When and how do we reveal the images; should we show the images we make immediately or is there a process of hiding them away in the “archive” whether that’s film strips or hard drives? These are all questions affecting how I’m working, usually curled around my laptop.

KE: As the traditional model of brick and mortar exhibition spaces become more difficult to sustain, both the arts organizations and the artist need to find solutions to sharing photographs. How best can an organization support the artist and visa versa?

AS: With our physical spaces in flux, temporal and digital spaces appear to be the new norm. I would suggest to arts organizations and artists to promote these digital spaces as spaces not just the holding space of images but spaces for continued meaningful conversation and connection around photography. Spaces where image makers can have dialogue and build connections with their audiences.

©Antonia Stoyanovich, Into the Black, 2015

KE: How are you finding community (online and in person) in a climate in which we increasingly rely on digital platforms to connect with each other?

AS: I find myself reaching out for more digital connections during coronavirus. There’s more time now for an extra DM here or there, or an extra ten minutes looking for new images makers to follow. It’s probably an extremely millennial thing to say but I love instagram. I’ve used it to connect, now more than ever, to dozens of image makers and photography platforms that inspire and push my own work but also make me feel a part of a diverse community of image makers..

KE: What are your thoughts on being a photographer today?

AS: Being a photographer today is more exciting now more than ever. We literally can’t interact with one another and yet we are producing images and we’re finding ways to share them. From everything we’ve seen Photography challenge so far in its short history, I can expect it’s going to adapt and bring us to even more questions that challenge the process of image making.

©Antonia Stoyanovich, Pair of Cowgirls, 2020

Antonia Stoyanovich is a photographer and visual artist currently based in the greater Detroit area. Using image-based media her practice expands the mythology of the American West into contemporary and physical content. Utilizing the image through photography, video, sculpture and installation she create relationships between fact and fiction to respond to current values of Americana and individualism. She is currently finishing her Masters of Fine Arts degree from Cranbrook Academy of Art (May 2020) and an alumna of The Cooper Union, School of Art where she received her Bachelor of Fine Arts (2016).

Instagram: @stoyvich

©Cassandra Klos, The Apparition, outside Auburn AL, 2019

By No Other Name

In a mythological Southern landscape, the natural world carves a pathway to a transcendence for its people. This landscape gives an outlet to derive belief, tradition, and spirituality from one’s deep connection to it. The water of a healing spring brings a community together to gather and bathe in its graces. The presence of natural rock formations brings one of the last indigenous flintknappers back into the woods to search for the abundance his ancestors once encountered. The search for the mythical Sasquatch drives an entire investigative effort by the ones who believe. A coven of modern witches use the landscape for clues of clairvoyance and celebration of its entirety. It is a quest for seeking the unseen, and looking for what others can’t. It is a search for comprehension of the lives we live outside of it. There is a search for an empirical truth – some find it, some do not – but all seem to lead to a transcendence.

By No Other Name examines the act of searching within this mythological Southern landscape. It is a visual narrative with nonlinear attributes, presenting no beginning and no end, but rather a series of moments that exemplify the curiosity of such an investigation of the natural world. In all experiences, there is an intentionality in turning their back on Southern preconceptions – finding their own mythologies and realities to depend upon, activating their communities with new ideas, and adding to the complicated and textured qualities of a Southern life. – Cassandra Klos

©Cassandra Klos, Jasmine of the Spring, Blacksville SC, 2019

Kellye Eisworth: In this time of social-distancing and greater isolation, how have you adapted your studio practice to the current situation, and and how is it impacting the work you’re making now?

Cassandra Klos: To be quite honest, my studio practice has not yet adapted. As a graduate student, my cohort has decided to make it our mission to make sure our school’s administration understands that without access to school laboratories, studios, and in-person learning; arts education cannot flourish in the same capacity. Without thesis exhibitions, graduating MFAs cannot bring our work to larger communities as we intended, earning valuable career skills, connecting with arts organizations, and find employment. The emotional labor is taxing enough to worry about the health of my family while wondering the state of my education.

Naturally, I am making photographs of my surroundings during Covid-19, truly, but the content and focus is very different that the projects I was working on prior.

KE: As the traditional model of brick and mortar exhibition spaces become more difficult to sustain, both the arts organizations and the artist need to find solutions to sharing photographs. How best can an organization support the artist and visa versa?

CK: I think significant adaptation needs to be made that allows for opportunities for artists to exist in the same capacity as brick-and-mortar exhibition spaces. Tastemakers needs to look at online/”virtual” exhibitions on a similar professional level as in-person exhibitions. This is not to say that photograph should only live in a virtual space, but that online should be a valid place to find photographers you want to hire, work with, have teach at your institution, etc.

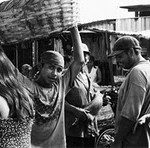

©Cassandra Klos, He’s Real, Troy NC, 2019

©Cassandra Klos, Dwight and the X, Uwharrie National Forest, Troy NC, 2019

KE: How are you finding community (online and in person) in a climate in which we increasingly rely on digital platforms to connect with each other?

CK: During Covid-19, I feel that finding community is the only thing anyone wants to do. I feel supported online as a graduating MFA possibly more than I would have had this not happened. The opportunities feel endless, and I hope that while the world is going through an extremely traumatic time, we also use the opportunity to change how we connect with one another as individuals. I’ve “zoomed” with more artist friends and communities during Covid than I did in the last few years in my own studio-practice; from friends that live down the road, to friends on the other side of the globe — from cohort members to complete strangers. Photographers are building each other up like never before. We have to hope that the industry will do the same.

KE: What are your thoughts on being a photographer today?

CK: I have always wanted to tell stories and bring stories to people. If I was not a photographer, perhaps I’d be a writer or a podcaster. The visual world is still so important; it’s important to make images, it’s important to critique the system of making images, and it’s important to develop alongside technology the ways that images exist. I love being a photographer because I feel that it’s a gratifying portal to so many other things. The current situation has not dissuaded me.

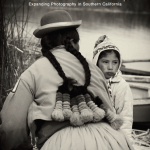

©Cassandra Klos, Scar/Heal, Blacksville SC, 2019

Cassandra Klos is a 2020 MFA candidate in Duke University’s Experimental and Documentary Arts program. Within her interests of science fiction, climate, and historical archives, she uses storytelling and photography as a way to breathe life into situations where visual manifestations may not be available. Her work has been exhibited and published across the United States and internationally, including solo exhibitions at the Griffin Museum of Photography, the Boston Public Library, and the Cassilhaus Collection and Gallery. Her work has been published in National Geographic, TIME, Bloomberg Businessweek, Wired, and Outside Magazine. She is a Kenan Institute of Ethics Fellow at Duke University, and a Critical Mass finalist.

Instagram: @cassandraklos_

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: jessamyn lovell: How To Become InvisibleFebruary 9th, 2026