Photographers on Photographers: Joe Harjo in Conversation with Mari Hernandez

© Mari Hernandez, Maria de Otra, 2017, inkjet print on photo rag, 24×36”

I first came across Mari Hernandez’s work when she was collaborating with Mas Rudas, a collective of Chicana artists based in San Antonio, TX. What struck me about her work, then, and has stayed with me as she’s evolved into a solo artist, is her unflinching braveness and willingness to take on multiple mediums without inhibitions. I appreciate her approach to photography, utilizing self-portraiture and doing so to speak so powerfully about identity. Voices like hers are needed and choosing to interview Mari came from my deep respect for her work, while recognizing the lack of representation of women of color in the arts and photography communities.

Joe Harjo: As an artist and thinker working in photography, how accessible has this medium been for you?

Mari Hernandez: When I think about accessibility in photography, I think about access to materials and equipment. Luckily for me, I’ve had access to a camera since I became interested in the medium. The first cameras I started using were a manual Nikon FM10 and a small point and shoot digital camera, both of them were basic, inexpensive, and easy to operate. I remember falsely thinking that in order to be a photographer or artist I needed fancy equipment and once I had access to fancier equipment I realized those tools didn’t make me a better artist. For me the camera is a tool that allows me to capture what I create. I prefer for the equipment I use to be minimal, that includes lighting and camera accessories.

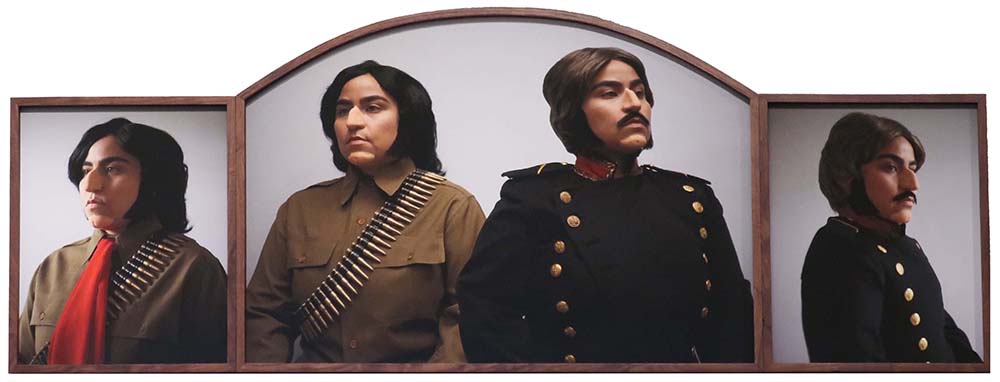

© Mari Hernandez, Colonizer, 2017, inkjet print on photo rag, 16×20”

JH: You mostly work with self-portraiture. Tell me about the process and importance of being the artist and subject.

MH: Self-portraiture is an ideal way of exploring issues of identity and it allows me to reference both internal and external conflict. I alter my appearance through the use of costumes, wigs, facial prosthetics, and makeup and create characters who are fabricated individuals. My process is heavily research based. I read a lot, I look at a lot of historical portraiture and painting. I think about how to make visceral emotion tangible. I work alone and act as the photographer and make-up artist, I set up the backdrops and figure out the lighting, find my costumes, etc. Working alone definitely makes the process harder and time consuming but I always end up learning a lot with every shoot. I am able to control all aspects of the process and work through problems, in the end this helps my work develop. The physical transformation I go through is personal and oftentimes uncomfortable, I prefer to keep those aspects of my process semi-private.

© Mari Hernandez, Untitled (4), 2019, inkjet print on photo rag, 8×10”

JH: As a woman of color, how do you deal with the misogynistic and racist history within photography?

MH: My work confronts issues of misogyny and race and offers an alternative perspective. Many of the themes that show up in my photographs such as power, war, appearance, and identity connect to these larger themes. My work is also an act of representation. Considering the power of images to dictate one’s place in society now and in the future, the portraits I make are a form of visual and historical documentation. I believe it’s up to me to leave a record of my experience as a Mexican-American woman in this world. Making self-portraits means I am both the sitter and the photographer. I am able to control what’s constructed on the other side of the lens, leaving no room for objectification and the male gaze.

JH: How do you deal with the present misogyny and racism in photography, photographic institutions, and within art in general?

MH: These issues that we struggle with today are rooted in our past. In order to emphasize this I try to bridge the past with the present through my work. Some of my work is black and white in order to reference the beginning of photography, the costumes I use are historically themed, and I study and mimic the pose and gestures found in historical portraiture of men. My current work centers around the theory of physiognomy, which was popular around the same time as early photography. The theory of physiognomy stated that a person’s physical features are indicative of their personality and identity. This theory was used to categorize individuals as good or bad, as prone to criminal behavior, and much more. Theories such as this have led to racial profiling and dehumanization. The use of facial prosthetics in my work, particularly the fake noses and chins, reference this theory. Through these techniques I am able to comment on how our past has influenced our present.

© Mari Hernandez, Untitled (5), 2019, inkjet print on photo rag, 8×10”

JH: What are your thoughts on the constructed notion of beauty?

MH: I believe beauty is culturally based and changes with time and place. My work pushes against notions of ideal western beauty and is meant to cause discomfort both in the viewer and myself. Challenging the relationship between self-portraiture and narcissism is also relevant for me. A camera is a great manipulative tool, it’s easy to take a photo of myself in the best light, from the most flattering angle and present an acceptable image of myself to the world, but that doesn’t define an artistic process for me. In making self-portraits I am intentional about disrupting what our society upholds as beautiful and redefining beauty on my own terms.

JH: What was your path to performative work?

MH: The self-portraits I make have evolved over time. I worked with an art collective called Mas Rudas for seven years before I started concentrating on my individual practice. The work I made with the collective reflected a desire to visually articulate a Chicana aesthetic and to embody cultural sensibilities. When I started working alone my practice shifted and I started to focus on the reimagination of histories. The aspects of performance that are present in my current work relate to my views on history and politics as performative. I have a degree in literature and studied theater for a while in school, this has also influenced my artistic practice.

© Mari Hernandez, The Signing, 2016, inkjet print on photo rag, 24×36”

JH: How are you using gender and identity to expose the power structures within our very colonized American culture?

MH: Frameworks of power keep social constructs alive, and gender and identity are things that those within power seek to control and dictate. When we define gender and identity on our own terms by our lived experiences, we disrupt this norm. I believe gender and identity can be fluid and I feel like my work reflects these ideas. For my work to develop I began transforming myself into male characters. I have a series of work titled Hombres, these self-portraits are all male characters who in some ways contradict our society’s views on gender and identity as static.

© Mari Hernandez, Pitted Brother Against Brother, 2019, inkjet print on photo rag, 54×26”

JH: As artists of color, we often find ourselves in white-dominated spaces that are culturally very difficult to steer. Do you feel like your rewriting of histories is, in some ways, an unlearning of the dominance we’ve been taught in these spaces as well as in American culture in general?

MH: Absolutely, learning to navigate white dominated spaces is a continuous process. I became interested in a career as an artist after I had graduated with a BA in literature. This was inspired by my initial confusion around contemporary art and frustration with the lack of representation of women of color in my arts community. The decision to become an artist is rooted in a desire to effect representation within the arts. This includes the representation of diverse ideas, experiences, and perspectives. In addition to a studio practice, I also work full-time as an arts administrator. The frameworks of arts institutions mimic the frameworks of our society. This means the same issues we confront day to day, such as race, accessibility, and representation are also issues within the arts. I’m concerned with dismantling dominant narratives and breaking down the boundaries that prevent equity within this field, in other words I work towards decolonization within the arts.

© Mari Hernandez, Vendido, 2017, inkjet print on photo rag, 16×20”

JH: Going forward, how would you like to see photography progress and what changes, if any, would you like to witness?

MH: I want to see the work of marginalized people elevated and given the platforms they deserve. We need equitable perspectives, and we must be intentional about seeking and exhibiting diverse voices. I would also like to see an increase in photo-based exhibitions. I appreciate the accessibility of photography and how it is referred to as one of the most democratic art forms. More people have access to a camera now than in the past and I think there’s a connection between accessibility to cameras and fostering an appreciation for the arts. Art creates bridges and contributes to the overall health of our communities.

JH: What’s on the horizon for you in terms of new or continuing projects and opportunities?

MH: Right now I’m slowly working towards finishing a few large-scale projects. One of those projects is my first public art commission for the City of San Antonio. Most of my plans for 2020 have been canceled and/or postponed due to covid. It’s been hard to make and be creative during this time, in a way it feels irrelevant in comparison to the issues our society is confronting right now. I’ve been working from home for almost 5 months and it has given me time to reevaluate the future. I feel a lot of uncertainty, but I will continue to push the boundaries of my artistic practice and develop as an artist. I’m confident that the turmoil of our present moment will serve as the basis for some new work one of the days, hopefully soon.

© Mari Hernandez, King Philip V of Spain, 2017, inkjet print on photo rag, 20×24”

Mari Hernandez is a multidisciplinary artist. A career in non-profit arts organizations led her to explore socially engaged and identity-based art, as well as its contributions to human and community development. Simultaneously, Hernandez became concerned with the lack of representation of women of color in her arts community in San Antonio, Texas. These experiences deeply influenced her artistic development. Inspired by appearance altering photographers and early Mexican-American artists, Hernandez began experimenting with self-portraiture to address questions about identity. As a co-founder of the Chicana art collective Mas Rudas (2009-2015), her self-portraits focused on Chicana aesthetics. Her solo practice is guided by these early influences, but Hernandez continues to expand her repertoire and skill base. Selected group exhibitions in San Antonio include The McNay Art Museum, Artpace San Antonio, the Institute of Texan Cultures, Centro de Artes and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas, Catherine G. Murphy Gallery in Minnesota, plus the Appalachian Center for Craft in Tennessee. Solo exhibitions include the Southwest School of Art and Staniar Gallery at Washington and Lee University in Virginia. Hernandez is a graduate of the National Association of Latino Arts and Cultures Leadership Institute and Arts Advocacy Institute, and she participated in the inaugural Public Art San Antonio Mentorship Course. In 2017, she was awarded the Joan Mitchell Foundation Emerging Artist Grant, and the National Association of Latino Arts and Cultures Fund for the Arts Grant. Hernandez holds a Bachelor’s Degree in English Literature from the University of Texas at San Antonio. She lives and works in San Antonio, Texas.

Follow her on Instagram: @mari.hernandez.210

© Joe Harjo, A Heretical Act of Resistance, 2018, video still (3:58 min)

Joe Harjo (b.1973 Oklahoma City, OK) is a multidisciplinary artist from the Muscogee Creek Nation of Oklahoma and is currently working and teaching in San Antonio, TX. He holds a BFA in Visual Arts from the University of Central Oklahoma and an MFA from the University of Texas at San Antonio.

His work uncovers the lack of visibility of Native culture, lived experience and identity in America, due to both the absence of proper representation in mainstream culture and the undermining of Native belief systems. He confronts the misrepresentation and appropriation of Native culture and identity, initiating a call for change.

Recent exhibitions include: The Only Certain Way, Sala Diaz, San Antonio, TX; Texas, We’re Listening, Brownsville Museum of Art, Brownsville, TX; We’re Still Here: Native American Artists Then and Now, McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX; Monarchs: Brown and Native Contemporary Artists in the Path of the Butterfly, Blue Star Contemporary, San Antonio, TX, Reimagining the Third Space, KCAI Crossroads Gallery: Center for Contemporary Practice, Kansas City, Missouri, re/thinking photography: Conceptual Photography from Texas, FotoFest, Houston, Texas.

Harjo is a board member of the Muscogee Arts Association, a nonprofit organization that advocates for living Muscogee artists. He is a 2020-2021 Harpo Foundation Native American Residency Fellow and a recipient of the 2020-2021 Blue Star Contemporary Berlin Residency hosted by Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Germany. He is the Chair of Photography at the Southwest School of Art in San Antonio, TX.

Follow him on Instagram: @NDNstagram

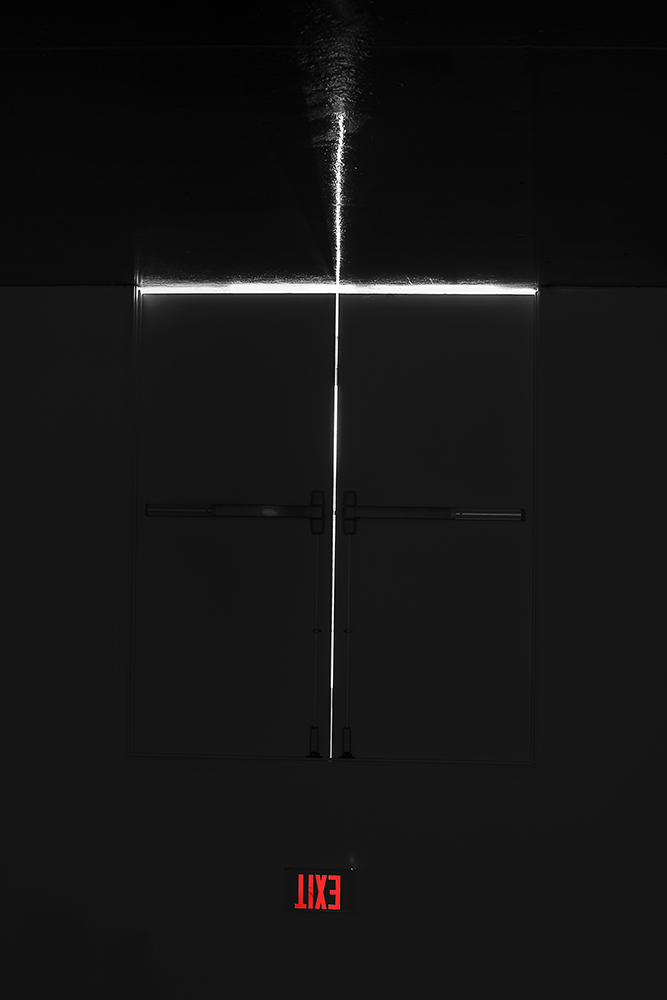

© Joe Harjo, EXIT, 2019, inkjet print on photo rag, 27×40″

Artist Statement:

My work uncovers the lack of visibility of Native culture, lived experience and identity in America, due to both the absence of proper representation in mainstream culture and the undermining of Native belief systems. I challenge what is societally considered “Native American” and what is not to dismantle the perceived spaces where, in the view of mainstream society, Indians are allowed and expected to exist as well as the visual notion of what an “Indian” should look like in those spaces. I confront the misrepresentation and appropriation of Native culture and identity, initiating a call for change.

-Joe Harjo

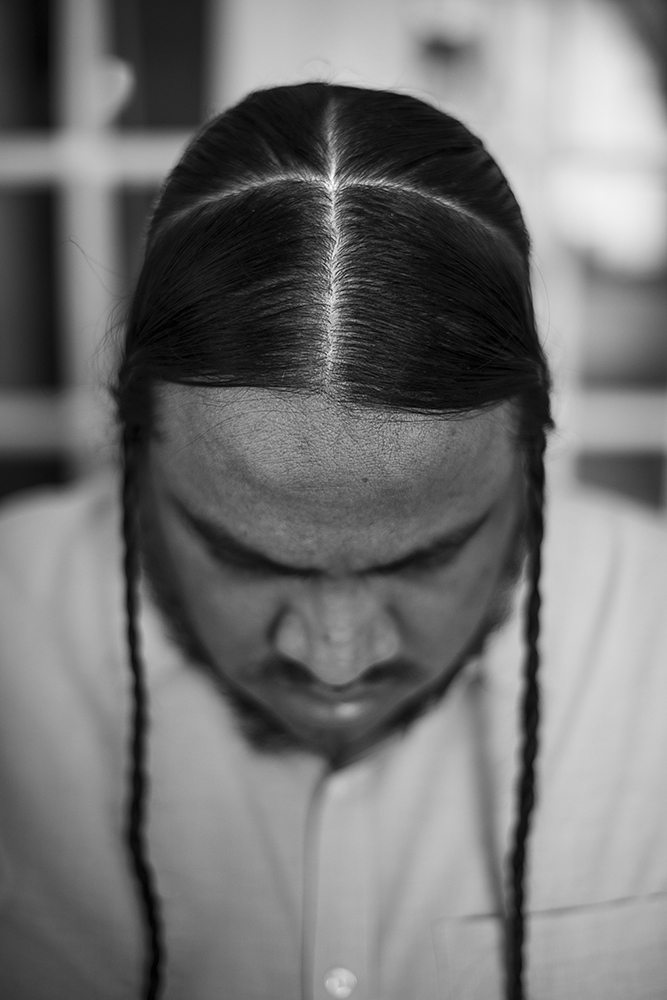

© Joe Harjo, Let Us Pray, 2019, Inkjet print on photo rag, 27×40″

© Joe Harjo, Mark of the Beast, 2019, inkjet print on photo rag, 27×40″

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024

-

Love and Loss in the Cosmos: Valeria Sestua In Conversation with Vicente IsaíasMarch 19th, 2024