Photographers on Photographers: Mercedes Jelinek in Conversation with Kris Graves

© Kris Graves, Murder of Michael Brown

Today we begin our Annual August effort, Photographers on Photographers, which features a stellar group of photographers in conversation with each other. Don’t miss a day of insightful interviews and we are excited to begin with Mercedes Jelinek in conversation with Kris Graves.

I first met Kris Graves while I was an undergrad at SUNY Purchase in NY. Since then, he has published two of my books, “These Americans” in 2017 and “Lost: Spruce Pine” in 2019, and we serve together on the board of Blue Sky Gallery in Portland. I have admired his imagery, commitment to the photography field, and unstoppable work ethic for as long as I’ve known him. It was a pleasure to interview him about his art, career path, finding inspiration, and the challenges of the art world in 2020. – Mercedes Jelinek

Mercedes Jelinek: Can you give an overview of your career path? How did you get to where you are now, from say, when you graduated college?

Mercedes Jelinek: Can you give an overview of your career path? How did you get to where you are now, from say, when you graduated college?

Kris Graves: I moved back to Long Island and worked at my father’s manufacturing company for about a year and a half. Then I started to split my time by working at a photography studio in the Chelsea Arts District in Manhattan. RIP that neighborhood. Ha. The studio focused on photographing artwork for museums, galleries, and artists. That led to me working as a photographer at the Guggenheim Museum from 2007 through 2018. I have since been a full-time freelance photographer.

On the personal side, I wanted to keep my community of art makers together after school ended. I started a website named nyfineart.com and featured portfolios of about 20 artists. We then rented out space in Chelsea and had huge group shows with concerning amounts of people at our openings. We did that about seven times throughout 2006 and 2007. In 2008 the economy crashed. My cousin and I decided to rent a cheap gallery space and showed photography and works on paper. We closed that in 2011 and switched our business model to publishing. We have produced about 90 books since 2014.

MJ: Do you feel like community played a big part in your career path?

KG: Yeah, 100%. I couldn’t have done most of the work without filling my life with the creativity of others.

© Kris Graves, A Queens Affair

MJ: Which photograph stays in your memory as the first successful image you made?

KG: I was walking through Astoria Park in Queens one late night with friends, about a year after college ended. We came across a Mr. Softee truck, which felt like it was glowing. The scene was “Queens-perfect” with the Triborough Bridge in the background. I think that’s been my most well-known image. I used to show it almost every time I was fortunate enough to exhibit.

MJ: How do you find inspiration to shoot During COVID-19 times?

KG: If I have eyes, I will always make photographs. Even if I had one eye and no hands. I try to focus my artwork on Western culture, and specifically gentrification, climate, and infrastructure. I’ve spent most of the pandemic on Cape Cod, away from a lot of my usual visual content. I still find some goodies up here. I was also fortunate enough to have gotten a job photographing for National Geographic in Virginia. That was extremely satisfying. Currently, most of my inspiration is geared towards bookmaking.

© Kris Graves, Childhood Diptych

MJ: Do you feel like anything is ever finished? Do you look at an image and say, it’s enough, it’s ready?

KG: Individual works of art, yeah. I think you can finish individual pieces within a series, and that’s for the artist to decide. Photographers have always worked in series. That is starting to feel like a detriment—a long conversation for another day.

When you think “I don’t want to work on this project anymore,” it’s done. You move on; you always have to move on. Make your work, get it out there, and make more work.

MJ: Can you talk a little bit about moments you’ve found it hard to make images and how you worked through those feelings?

KG: Um, well, it’s hard for me to make work. Most of the time, just because I aim to find something culturally relevant in the world. So that’s usually figuring out where I need to go to make that work. At home in Queens, I focus on works about the gentrification of my neighborhoods. All of my other work is basically an extension of my main series of Queens photographs. I recently went down to Richmond; I made some good photographs there, even a few that National Geographic will definitely not use, but that I like. There’s some weird stuff in America.

I don’t get sad or depressed about it; I just do it. I mean, at this point, if I go outside for a full day to make photographs, I hope to come back with at least one decent image. It may be a good photograph, but I do it for the learning experience. Hopefully, I can be better next time. Say I was on a boring walk and took a bunch of pictures. I come home after and try to figure out if something is good, but it usually ends up being just a way to practice. If I’m not doing work that’s important, then it’s practice, and then, you know, you keep moving. Sometimes there will be a day where that practice pays off.

© Kris Graves, Yat Tung Estate, Hong Kong

MJ: What details do you think make the best photographs?

KG: If a picture is devoid of cultural reference, then it’s not necessarily for me. I refuse to fall in love with a beautiful landscape of trees in a forest. Show me the struggle! I want to see that within the picture when I look at it. I don’t want to have to read about your context; I want to see your context. That’s why we make photographs in the first place.

It’s hard to answer that question because a landscape is so different from a portrait. Sometimes there’s no way to qualify or quantify what’s going on in them. I usually like photographs that are in focus: focus and culture. Personally, I want my family to be able to comprehend my work. Art shouldn’t be geared towards the art educated.

© Kris Graves, Waterfall, Ithaca

MJ: Do you ever feel like you had to unlearn certain things after college?

KG: Unlearning the history of photography is important. As the years go on, I realized that the photography education that we got is very limiting. They didn’t teach so much about the culture, it was mostly about form and shape, especially at the school we went to. I learned a lot about form and shape, and then the culture was added when I was out seeing what was going on in our world. I’ve become way more aware of the history of photography and how much I don’t like it. Does the world need another Eggleston show? We learn from them, and they’re important to our history, but there’s also a history of photography that we’re just not taught. I didn’t know anything about African artists, Asian artists, anybody besides us Westerners. I’m sure that there’s a Harry Callahan in Africa that no one ever heard of. So I think photography education is very limiting. It can make you better at photography, but it can also put you into a place where you’re only creating decorative artworks. This, too, needs a way longer conversation.

MJ: Which photographers have influenced you most?

KG: Early in college, I was influenced by Eugene Smith, Gordon Parks, Stanley Greenberg, Lois Conner, and Roy Decarava. Later in college, I became a German and followed the work of Thomas Struth and Andreas Gursky. These days, I am influenced and inspired by a huge list of my peers. Our publishing house works with a lot of artists that I am compelled by.

© Kris Graves, Discoverer of America

MJ: Tell me about the photo series you’ve been working on right now.

KG: Well, I’ve been working on one called “Reverie a.k.a. Privileged Mediocrity,” where I’ve been traveling around America and Western nations; photographing the bullshit that happens within them, the racism in the landscape and more. Right now, it’s all about these old statues, memorials, and monuments. There are also infrastructural problems everywhere, environmental issues like fracking. The project is almost complete, and I hope to have a book ready within the year.

MJ: So what is it that you want to say with most of your photographs? What do you see is the central theme in your work overall?

KG: I think there needs to be a cultural shift in the Western world. I would like not to have my children suffer through the same things that have been happening for the last 300-400 years. I don’t want this to keep going on. We can live in this bullshit world for 300 more years or until we all burn, but it would be great to have real equality. And that’s why I want to make work. Doing projects, as well as producing books, are forms of tangible equality.

MJ: The world has changed so much. How have recent events in the world altered how you work or how you perceive the world?

KG: Well, I think I started making different work back when the Black Lives Matter movement started five or six years ago. I was photographing murder scenes where police officers murdered black people. So for me, it changed right around when people were being killed on camera. And that’s when I tried to start changing the way I thought about artwork.

The world always changes. It seems like it’s changing a lot, but not much has changed yet. More black people have gotten jobs, which is important. That’s a big change, but there’s still a lot of people that don’t have any opportunity, and there’s a lot of privilege that comes with being a photographer. I hope we can finally break down some barriers to getting people of color into some of the artistic positions.

© Kris Graves, Colonial Man

MJ: What’s it like being an artist of color making work right now?

KG: I have no idea what it’s like not to be a black artist. Being an artist is just being an artist. I’m trying my hardest to get stuff out there. I get a lot of opportunities that a lot of people don’t get, so I feel very fortunate. I work all the time. I feel like if you work all the time, maybe something will eventually happen. I think that there is a difference between working all the time and getting your work out there. You can work in the darkroom for 40 years, but if you’re not relevant in culture or can’t get a job or show your work, then people won’t know you exist. You become irrelevant in the cultural world where people are moving things forward. You are not part of the conversation, which means it’s a detriment to your art—what a tough statement. Sadly, I have no patience for artworks that don’t deal with trying to change the terrible place we live.

MJ: What advice would you give to the art world right now?

KG: Fire the people that run museums, hire different people. Trickle-down. You have to have a lot of money to be on a museum’s board, and you have to have a lot of influence, all that stuff needs to start changing. I’m just going to go out on a limb and say that if you look at all the major art institutions in America that well under 25% of the people on the boards of those institutions are people of color. I’m going to go out a bit more and say that, maybe even less than 25% are women. So, there’s a low percentage of diversity on the boards, and a very low percentage of the directors of museums are people of color.

I don’t think the museum world is culturally relevant right now. Run tell that! I don’t go to see most shows that happen in museums lately. I can only speak about photography in museums because that’s all I know. There’s rarely a major museum show in photography that I want to check out because things haven’t changed. They’re still not showing me. By me, I mean, they’re not showing people of color in these spaces. When they do, it’s one of the eight black photographers that you’ve already heard of that have already gotten all the opportunities.

© Kris Graves, Stone Mountain Confederates

Kris Graves (b. 1982 New York, NY) is an artist and publisher based in New York and London. He received his BFA in Visual Arts from SUNY. Purchase College. He has been published and exhibited globally, including the National Portrait Gallery in London, England; Aperture Gallery, New York; University of Arizona, Tucson; among others. Permanent collections include the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Brooklyn Museum, New York; and The Wedge Collection, Toronto.

Graves also sits on the board of Blue Sky Gallery: Oregon Center for the Photographic Arts, Portland, and The Architectural League of New York as Vice President of Photography.

Kris Graves creates artwork that deals with what he views wrong with American society and aims to use art as a means to inform people about social issues. He also works to elevate the representation of people of color in the fine art canon; and to create opportunities for conversation about race, representation, and urban life. Graves creates photographs of landscapes and people to preserve memory.

Instagram: @themaniwasnt

© Mercedes Jelinek, Bare Truth – Finding Scarlet series, 2020

Mercedes Jelinek (b. 1985 New Haven, CT) is an American artist working in Italy and NYC. She holds a BFA in Visual Arts from the State University of New York at Purchase and an MFA from Louisiana State University. She recently completed the three-year residency at Penland School of Craft in North Carolina. Her work has been exhibited both nationally and internationally, including the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in Louisiana; the Hinson Art Museum, Gaston County Museum, Blowing Rock Art and History Museum and the Cassilhaus Gallery in North Carolina; SoHo Photo Gallery, Cuchifritos Gallery, Littlefield Gallery, and Gallery MC in New York; Page Bond Gallery in Virginia; the Satellite Art Show at Art Basal Miami; 30-under-30 Exhibition at Vermont Center for Photography; MPLS Photo Center in Minnesota; Midwest Center for Photography Exhibition at the Center Gallery in Kentucky; among others. Mercedes’ second book, Lost: Spruce Pine, published by Kris Grave Projects in New York City, was launched this past July and was acquired by the Guggenheim Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Whitney Museum, Library of Congress, Aperture Foundation and the Getty Institute collections. She is also on the board of Blue Sky Gallery in Portland.

Mercedes Jelinek is a photographer who specializes in black and white portraiture. Her curiosity about the variety of humanity drives her work. The resulting images reflect the personal connection she makes with her subjects.

Instagram: @mercedes_jelinek

© Mercedes Jelinek, Reach – Finding Scarlet series, 2020

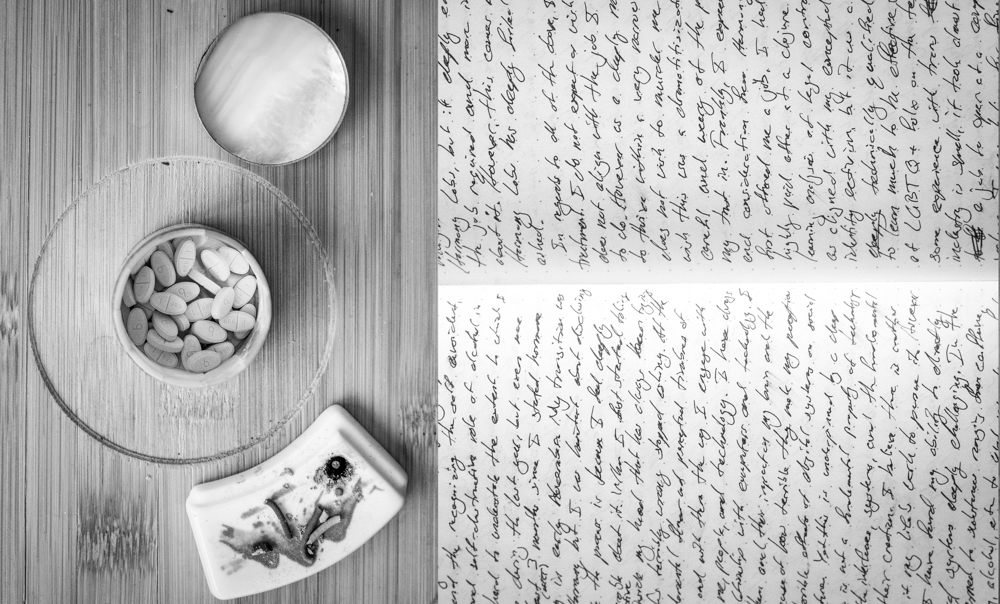

© Mercedes Jelinek, One Pill, Two Pill – Finding Scarlet series, 2020

© Mercedes Jelinek, Listening to the Landscape – Venice is Flooding series, 2019

© Mercedes Jelinek, Watching the Water Rise – Venice is Flooding series, 2019

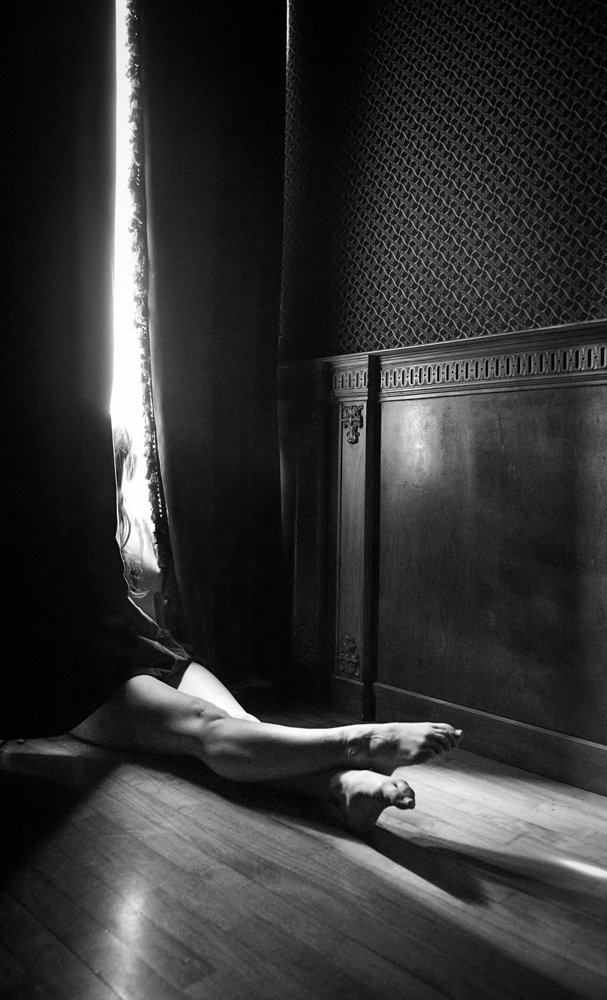

© Mercedes Jelinek, Tiny Dancer – Perform series, 2019

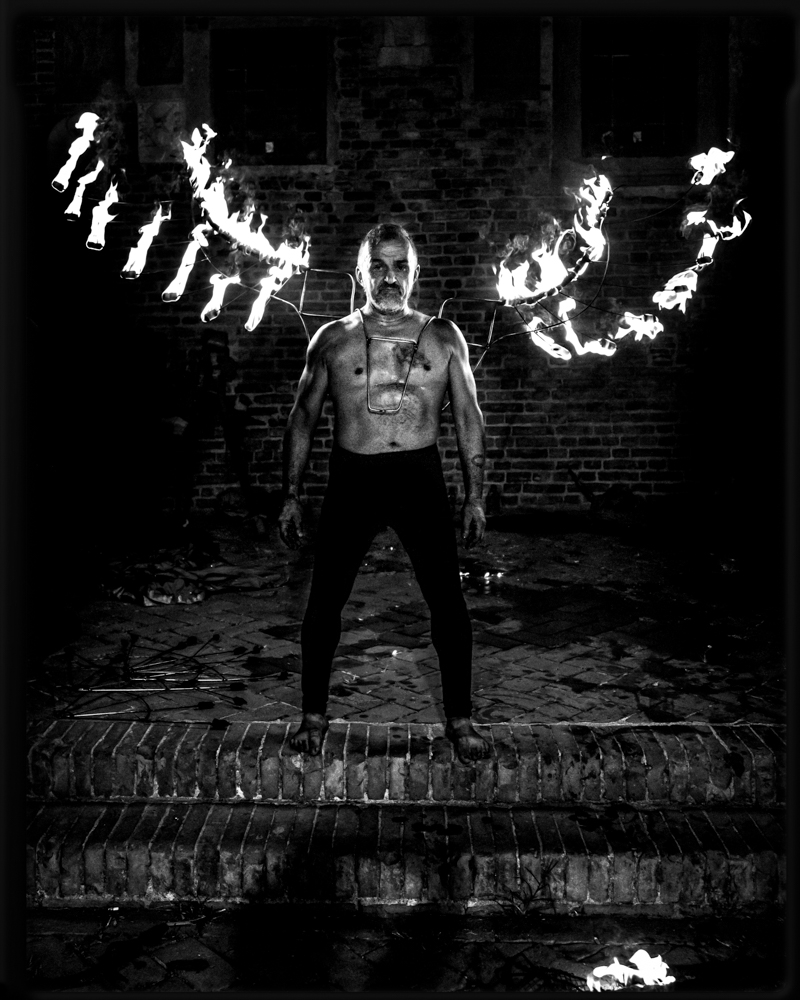

© Mercedes Jelinek, Leandro – Perform series, 2019

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026