Focus on Gallerists: Catharine Clark of Catharine Clark Gallery

Amy Trachtenberg and LigoranoReese, installation image from Open Field at Catharine Clark Gallery, 2021. Courtesy of the artists and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco. Photo: John Wilson White.

Continuing our series of interviews with gallerists, we turn to Catharine Clark and her eponymous gallery, based in San Francisco. Community-minded and strikingly steadfast in her support of the artists on her roster, Clark calls forth a wealth of thoughtful experience and nuance surrounding her gallery’s role in the art ecosystem-at-large.

Established in 1991, Catharine Clark Gallery exhibits contemporary art in all disciplines. The gallery’s program has garnered critical attention from publications: the New York Times, Yishu, Artforum, Tema Celeste, Art in America, Art News, Art Practical, Modern Painters, i-D/Vice, and Vogue. Gallery artists have exhibited at international venues and biennials: the Tate Modern, the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Asian Art Museum, the Serpentine Gallery, the Frans Hals Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Mori Art Museum, the StadtReutlingen Museum, Manifesta 11, and the 56th Venice Biennale.

In 2016, Catharine Clark founded BOXBLUR, an initiative to bring visual and performing art into dialogue within the non-proscenium-based space of the gallery. Located within San Francisco’s emerging DoReMi arts district, Catharine Clark Gallery is situated in proximity to leading arts venues such as California College of the Arts (CCA), the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, the Museum of Craft and Design and Minnesota Street Project, as well as several contemporary fine art galleries.

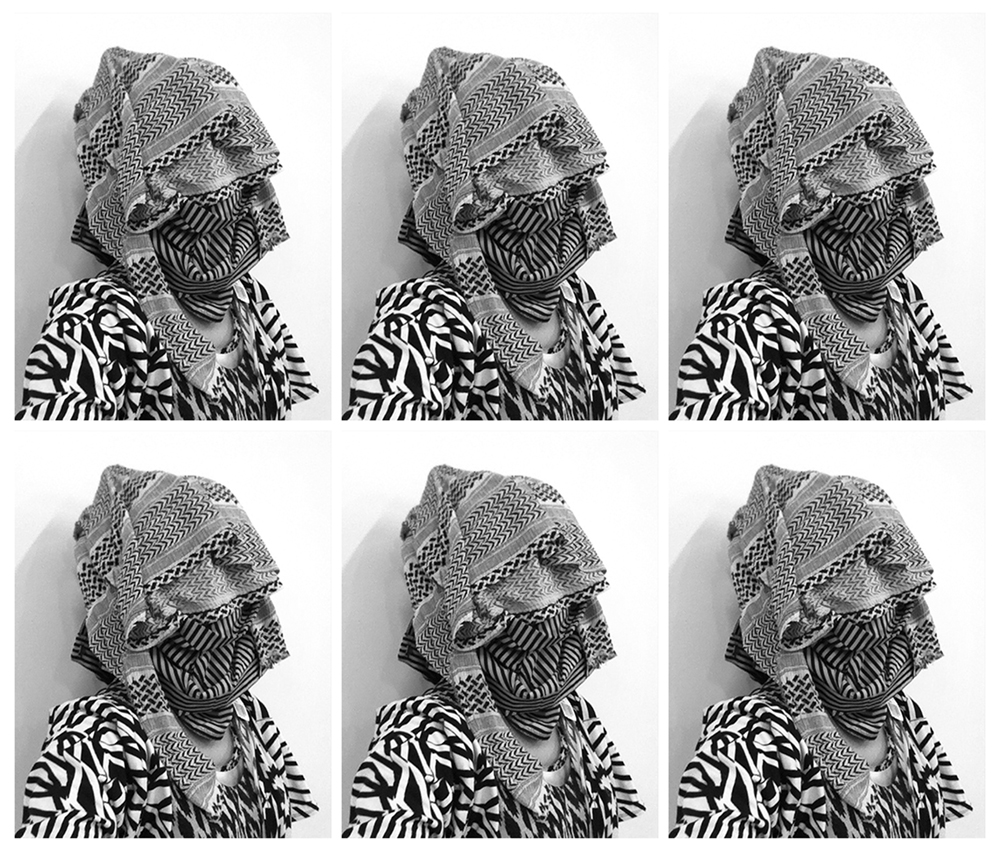

Leilah Talukder, installation image from Open Field at Catharine Clark Gallery, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco. Photo: John Wilson White.

Erica Cheung: Will you walk me through the inception of your space and how it came to be?

Catharine Clark: I got started in 1991—during a time of recession. I was twenty-three, and like many young people, I was all aspiration and little actual knowledge. In some ways, that was good news because I didn’t particularly understand the risk involved. I started paying rent—about $300 a month—on a space that I shared with an artist. It was in a neighborhood that is now quite fancy, but at the time was crime-ridden and had a collapsed freeway down the middle of it because of what had happened in the 1989 earthquake.

I was in that area from ‘91 to ’95, and my gallery was called Morphos Gallery. I approached it like a project, where artists I knew in the Bay Area who were not having opportunities to exhibit could engage with me. From the gallery’s inception, we featured performing artists, had readings, and the like. The seeds of who I am are certainly there, and even a couple of the artists from then are still with me today. It didn’t start in a practical way with a business plan; it started from a place of passion and interest in creating a community of creatives around myself.

In ’95, I moved to 49 Geary, which was one of the densest gallery buildings in San Francisco at the time. I still worked on Mondays for some awful corporation in order to support myself, and I taught at the Art Institute. There were other revenue streams to help me keep going, and there were some key supporters early on that really gave me faith in the possibilities. One of them was Rene di Rosa, who was very much a champion of Bay Area artists and regionalism at a time when those ideas were not popular.

He was there for me through what then proved to be, again, difficult times. In 2000, we had the big Dot-bomb in San Francisco. For a while, there was an anti-arts, anti-gallery feeling as landlords saw their future in tech instead. I think that reputation then plagued the art world here for a long time, and maybe continues to in some ways. But I stayed in 49 Geary until 2007, when I moved to Minna Street. The space was in an alleyway next to SFMOMA, and this proximity made it easier for curators and collectors to wander in. I really loved being there, but when the museum started expanding around 2012, it became evident that it was going to be very hard to stay. So I moved to my current location on Utah Street, where I have been for almost nine years.

Nina Katchadourian, installation image of To Feel Something That Was Not of This World at Catharine Clark Gallery, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco. Photo: John Janca.

EC: Given all of these twists and turns, why have you chosen to stay in the commercial world, as opposed to moving into another place in the arts—i.e. a museum?

CC: I really love the relationships that come from having a commercial gallery, and I love helping artists be self-sustainable. All aspects of the art world are important, right? We need people who write about art, we need people who talk about art, we need people who show it.

I work with twenty artists. I’ve worked with at least a third of them for more than twenty years. Another third I’ve worked with for at least ten to twelve years, and the rest are somewhere in between. I value long-term relationships, and I feel like I’ve been criticized for this at times—like, “oh, another show of this person?” My response is that that’s my commitment to the artist.

Maybe it’s the value I place on community. All the different parts of the art ecosystem—the collectors, the curators, the regular people—all come around this one thing, which is the art. We as a gallery work very closely with museums. For example, we helped the Blaffer Art Museum fundraise for Stephanie Syjuco’s show there. Some other gallerists might think I’m crazy to be spending my time that way, but I’ve just always had this sense that we need to join together to make this happen. And by ‘this,’ I don’t just mean an artist’s career. As one of my directors once said: I like eating, too.

We all need to be—and can be—supported by supporting each other. I see more of this going on in this pandemic period than I’ve seen in a long time, and I think that it’s healthy. Maybe we’ve shifted our ideas of what it means to be human, and what it means to support our fellow humans.

Stephanie Syjuco, installation image of “The Visible Invisible” from “Stephanie Syjuco: The Visible Invisible” at the Blaffer Art Museum, Houston, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco. Photo: Simon Fujiwara.

EC: Yes—I’ve seen how in places like San Francisco and New York City, galleries who very well may be in competition for a similar art market and a similar group of collectors are coming together and forming collective groups and coalitions.

CC: And it’s different. I haven’t seen this kind of thing until now, and it also feels like it’s not just about art. It’s bigger than art. It’s more about the role that art can play in this larger conversation about what it means to be an American, what it means to be human, etc.

For our project in the fall, Night Watch by Shimon Attie, we’re working with thirty different organizations. These organizations are not just arts organizations; they are Cal Sailing Club, and International Rescue Committee, and Partnerships for Trauma Recovery, among others. People read about the project, which has to do with the human dignity of refugees, and the first thing they say is, “How can I get involved? How can I partner with you on this?”

EC: I want to pick up on the thread of how many of the artists you represent have been on your roster for a long time. Some, I imagine, were emerging when you first began to show them. How have you been thinking about the age-old question of how to balance financial viability for your gallery alongside passion for showing newer artists?

CC: I know what I like and what I feel is important. I operate from the position that if I believe in something, and I can talk and write about it, and I can get others to talk and write about it, then I should be able to find the few people on the planet that are perhaps interested in supporting it. This comes from an incredibly deep place of optimism. Maybe it comes from having parents that valued the arts—most of our time was spent in museums, going to festivals, listening to music. Maybe it’s because I don’t have a business degree, but rather a degree in art history. I used to be a dancer. These are fields that you don’t go into to make money. You go into them to fulfill your dreams and feed your soul.

To answer your question—I just keep believing until other people start believing, too. Certainly things like art fairs can be helpful to help grow an audience for an artist’s work. I have mixed feelings about art fairs; I feel they’ve been the undoing of the art world in a certain way. On the other hand, taking Stephanie Syjuco’s work to Paris Photo, for example, really opened doors for her. Lucy Gallun, the curator at MoMA, saw the work there, put it into the New Photography show at MoMA in New York, and that really changed things. I believe Stephanie would’ve gotten to where she is anyway, but some of the choices we made helped to expedite that path.

Stephanie Syjuco, installation image of Cargo Cults and Applicant Photos (Migrants) from “Being: New Photography 2018” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco. Photo: Martin Sack.

Stephanie Syjuco, Applicant Photos (Migrants) #3, 2017. Pigmented inkjet print. Sheet: 3.6 x 4.2 inches; Frame: 20 x 16 inches. Edition of 10 + 2AP. Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco.

EC: I wonder if your longstanding commitment to the artists you represent precludes you from showing more emerging artists.

CC: We do a curated group show every summer—we just opened one, in fact. It’s an opportunity for us to work with artists both in and outside of our program, which means sometimes we borrow from other galleries, and sometimes we work with really emerging artists. Often, we’ll work with someone we really love in our community who might not be represented by a gallery right now, but whose work we’ve seen at many different places.

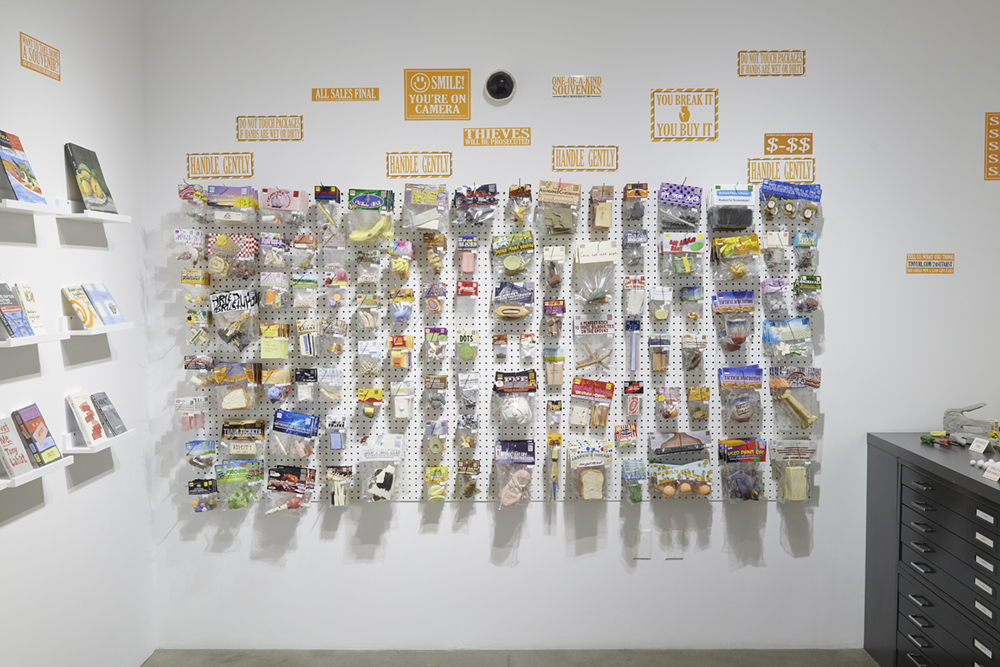

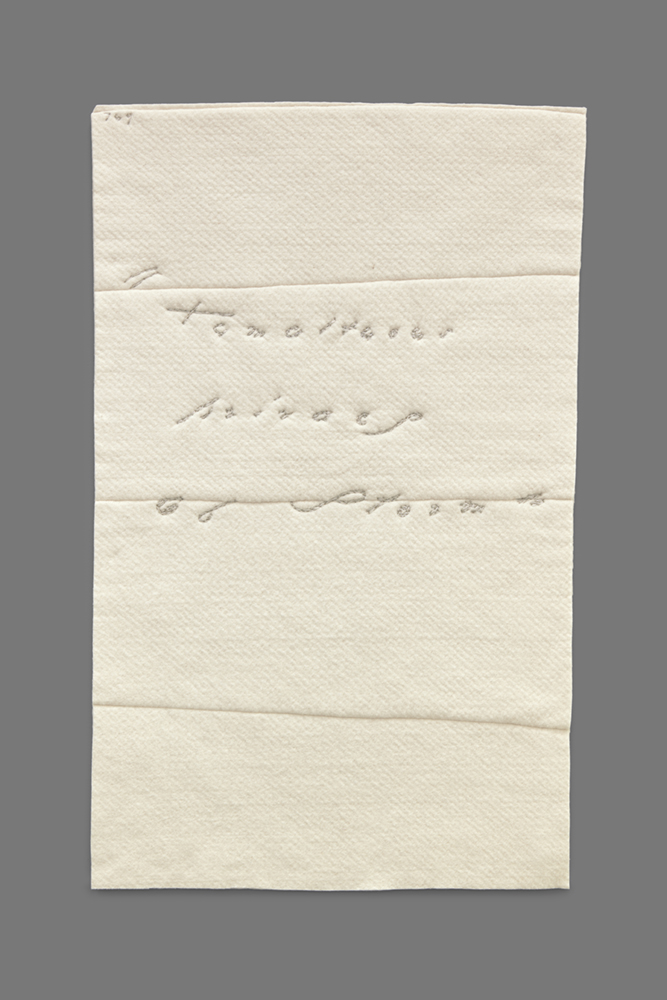

Our current exhibition, Open Field, has nine artists in it. Two of them are former students of Stephanie Syjuco’s—Reniel Del Rosario and Leila Talukder. Another, Jen Bervin, just had her first solo show with us. She’s an interesting example because on the one hand, she’s mid-career in the sense that she has received Creative Capital grants, her work is in many museums, she’s been critically well-reviewed, and so on and so forth. On the other hand, she’s never really had a solo show in a gallery in which she’s sold work. The process was new for her, so in a sense, she’s emerging and not emerging. Emerging in the gallery scene, but with a very strong history.

At this moment, I am, in some ways, more interested in artists like Jen than the most emerging. That’s partially because I’m now a middle-aged person, and I want people to give us opportunities that we haven’t had. I also think being middle-aged, by some people’s perception, is the least sexy place to be, whether it be an actual age, or being at that point in your career. It neither has the sparkle of being of youth, nor the sagacity of age. I think we’re often drawn to artists that reflect something about our own position in life.

Reniel Del Rosario, installation image of Exist Through the Gift Shop at Catharine Clark Gallery, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco. Photo: John Wilson White.

Jen Bervin, Close Reading 769 “ ‘Tumultuous privacy of Storm’ ”, 2021. Cotton batting, muslin, mull, silver thread; text reads “Tumultuous privacy of Storm”. 43 x 27 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco.

EC: What are your expectations of the artists on your roster?

CC: I know there are myths out there—some of which might be true—of galleries telling artists that they must make a certain kind of work, or that they won’t show particular types of work. Early on, I read an article about a major gallery in New York, and the gallerist was quoted saying how once they decide to work with an artist, they trust that the artist is smarter than they are in terms of what the art needs to be. That’s where I operate from. I’m surrounding myself with people who I think are pioneering in their fields, so why would I assume to know what they should be doing with their work?

I really want the artists to understand what a gallery’s loyalty and commitment to their careers mean. It’s an investment. Let’s look at Nina Katchadourian, who is represented by Pace in addition to us. I’ve worked with Nina for 23 years, and when Pace approached her about representing her internationally, I couldn’t really compete with that. That being said, you could argue that our gallery has played a significant role in her career. Fortunately, we struck a relationship with Pace that protects my gallery—in the sense that we get to exhibit her work wherever we want, that every museum show has both galleries on the label—and it feels really positive.

I’m sure Pace could completely crush me if they wanted to. Yet they’re working with Nina, and she has the agency and capacity to sustain our relationship. Pace, in turn, has been nothing but easy to work with—communicative, gracious. They said something to me like, “hey, you guys need us, and we need you,” and that in general, smaller galleries need larger ones and vice versa, and we should make this work collaboratively.

EC: I’m glad to hear that. I feel like there is an overarching sentiment out there that smaller galleries are just feeders into, say, the Gagosians of the world. And I have to think that this scarcity mindset comes out of a model where artists are things to be profited off of, and artists will go to a larger gallery if doing so is deemed more lucrative.

CC: I wish that I could empower some of those artists with the confidence to say, “Yes, I will work with you, but this gallery has been with me for x amount of time, and they need to be respected and honored in some type of way.” I think the Nina example proves that it’s possible, but I think artists often feel intimidated by gallerists. A lot of galleries present a picture of all-or-nothing—why do you need that gallery, we can do so much more for you, etc. A gallery of my size can’t be everything to an artist, right? I need people, too. I need galleries working in other places in order to help realize the artist’s potential.

Nina Katchadourian, installation image of “Lavatory Self-Portraits in the Flemish Style” from “Nina Katchadourian: Curiouser” at the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas, Austin, 2017. Courtesy of the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco, and the Blanton Musuem of Art, The University of Texas, Austin.

Nina Katchadourian, Lavatory Self-Portrait in the Flemish Style #3, 2011 (“Seat Assignment” project, 2010 – ongoing). C-print. Sheet: 13 x 10 inches; Frame: 15 x 14 3/8 inches. Edition of 8 + 2AP. Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco.

EC: I want to acknowledge that you are a small operation. It’s only the three of you, and it’s wild to think that three people are responsible for the careers of twenty different artists.

CC: It’s a big job, and the reason why we can be three people and be as effective as we are is one, we’ve been around a while, and two, my staff and I work really, really hard. Even if we’re all ‘art laborers’ as my director likes to call us, I think we could also all work in other fields, and we’re choosing this one. There’s something about that agency, about it being worth it to work that much. I am fond of saying I expect the artist to work as hard as we work for them.

EC: And then the third part of that relationship is an audience that is receptive and willing to trust what both the artist and the gallerist are putting out there.

CC: In terms of audience, I just ask that people come in with an open mind. I’m happy to talk with anybody about the work and the ideas behind it. One of the things that has developed over the years in the art world—something that I feel a bit wistful about—is the shift away from how people used to take lunch hours, and how we would see a surge of people coming in between 11 and 2. That just doesn’t happen anymore because our world has changed, and the way people work has changed.

The art world has also become very event-driven. People will say to me, “I’m sorry I missed your opening,” and I’ll say, “That’s okay, the show’s still up for six weeks.” There’s this sense of if you didn’t come at that moment, then it’s over. I would like to figure out how to tackle that barrier, because that’s a big shift from when I started.

Stephanie Syjuco, Pileup (Eastman), 2021 from “Stephanie Syjuco: Native Resolution” at Catharine Clark Gallery, 2021. Hand-assembled pigmented inkjet prints on Hahnemuhle Baryta. Sheet: 47 x 35 inches; Frame: 48 x 36 inches. Edition of 3 + 2AP. Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco. Photo: Torin Stephens.

EC: Do you think the influx of all our digital technologies, also coupled with a pandemic, have exacerbated that?

CC: I think the pandemic weirdly did something good for the art world. Because people had to make appointments, there was a different kind of relationship valuing the experience of looking. People came in more purposefully.

But in general, the way that people engage with galleries now reflects a change in our culture from analog to digital experiences. The idea that you can experience something as well online as you could in person is heightened by the proliferation of organizations like 1stdibs and Artsy. In the same way that I don’t really want to use Amazon, sure enough there was a package at my front door today. The ease of access gets in the way of our hopes for our own behavior.

I really believe in the aura of the physical object. I think it’s why we go to museums, why we show up at galleries. There’s something very kinesthetic about residing in the shadow of a work. While I don’t think this is exchangeable with an online experience, we do try to create virtual experiences for people—we use something called Kunstmatrix, a program that people can use to move through our shows, and we use a Matterport camera. We’re not total luddites; we’re trying to meet the needs of our audience’s changing desires. But for every single person who looks at a show that way, I wish I could just transport them into my gallery and say, “Engage with this physically, it does something for you.”

Catherine Galasso, performance still from Dances for Doing, 2021. Dancers: Phoenicia Pettyjohn, Karla Quintero. Commissioned by BOXBLUR and the San Francisco Dance Film Festival.

EC: What’s next?

CC: Currently on view is our exhibition Open Field. The show looks at the ideals of Black Mountain College, considering its impact on artists of now. It values the interdisciplinary, and it includes a landscape architect, somebody who set up a ceramic store, and somebody who works at the space between fashion and sculpture—as well as textiles and video and other media. Another cool aspect of the show is that we’ve commissioned two choreographers—Catherine Galasso and Emma Lanier, the granddaughter of Ruth Asawa—to create dance performances in the space. That’s part of an initiative that we started five years ago called BOXBLUR, which brings performing artists into conversation with visual artists’ works in the space.

In the fall, we have the Shimon Attie project Night Watch. It not only takes place in my gallery, but also in spaces all over San Francisco—including a barge on the Bay itself. We’re creating site-specific activations with music and dance, incorporating music from the diasporas and performers who are, or were, refugees. We’re collaborating with San Francisco Contemporary Music Players and San Francisco Dance Film Festival within the gallery to produce an evening of experimental dance films that deal with the other issues in the show, which not only have to do with safe harbor, but also with authoritarian governments—the rise of them, their history, and the absurdity of them. It’s a complex project called Time Laps Dance, which was originally commissioned by the Wexner Center.

EC: Definitely all things best seen in person.

CC: Yes! Well, come on out and visit us.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Suzanne Theodora White in Conversation with Frazier KingSeptember 10th, 2025

-

Maarten Schilt, co-founder of Schilt Publishing & Gallery (Amsterdam) in conversation with visual artist DM WitmanSeptember 2nd, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025