Focus on Gallerists: Arnika Dawkins of Arnika Dawkins Gallery

Like many in the art world, Arnika Dawkins dons many hats. An enthusiastic artist, collector, and gallerist rolled into one, Dawkins is poised to sustain relationships with the artists that she champions while simultaneously speaking an art buyer’s rhetoric. Her gallery, Arnika Dawkins Gallery, is located in a cottage house in a residential neighborhood of southwest Atlanta—perhaps one of the coziest places to see something necessary and lovely.

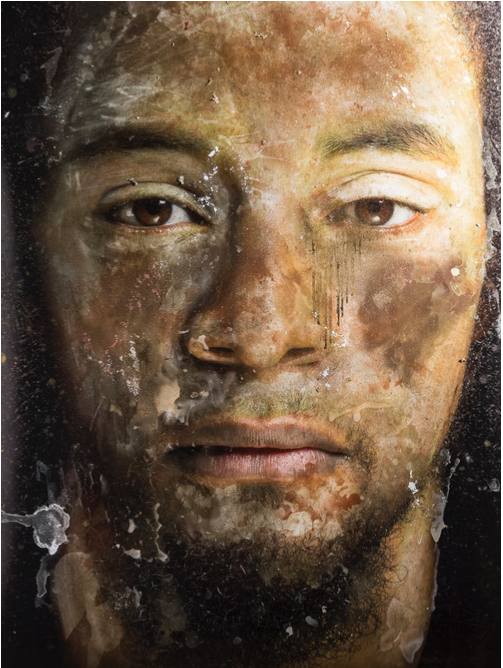

Arnika Dawkins Gallery is devoted to presenting fine art from both emerging and established photographers, specializing in images created by artists from African Diaspora as well as images of people of African descent. Some of the talented artists represented include The Bethencourts, Najee Dorsey, Delphine Diallo, Ervin A. Johnson, Builder Levy, Jeanine Michna-Bales, Gordon Parks, Keris Salmon, Aline Smithson and Wendi Schneider. Launched in 2012, the gallery’s objective is to provide an educational platform that supports this burgeoning community of artists. The gallery is a member of the Association of International Photography Art Dealers (AIPAD).

Erica Cheung: To start, will you tell me how your gallery came to be?

Arnika Dawkins: Pretty early on, I became a shutterbug—and my muse were my children! After working in corporate America, I became a stay-at-home mom and a volunteer. I loved photography through the years, and I found myself at weddings and events composing pictures.

When my role as a stay-at-home mom began to change as my youngest child approached high school, I decided to take photography very seriously. I went and got my Master’s in Digital Photography at the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD).

Once I received my degree, I found myself wondering, “okay, so now what am I supposed to do?” I figured I could be behind the camera, I could work at a gallery, or I could own a gallery. I did some work at a local gallery in town and fell in love with the process, with talking to the artists, with meeting collectors and talking about what they were buying. It was a no-brainer that this was what I wanted to do.

EC: Why did you choose the commercial art world specifically to realize your love of the arts, as opposed to another realm?

AD: I think it’s because my husband and I are collectors of art. When we lived in the northeast, we would often go to museums and galleries. We always loved these visits; the ecosystem that arts organizations provide for artists is so important.

I was drawn to the artists’ stories, their backgrounds, and the intentions behind their creativity. As a creator as well, these aspects all resonated deeply with me. As a collector, I understood what it takes to choose artwork, live with it, and ensure that you’re buying something that enriches your life and stands the test of time. Overall, I thought that there was a need to show work by talented artists who may not be in the network of having their work seen by a wider audience.

You’re right, I could have gone in different ways—but I was particularly fascinated by the direct interactions between artists and collectors. It’s an intersection that I find really gratifying.

EC: I love that. I wonder how you think about the fact that commercial galleries are, at the end of the day, businesses with a bottom line to sustain. How do you find the balance between financial viability (showing work that is likely to sell) versus passion for work that might not be as tried and true in the art market?

AD: That’s an excellent question. My simple answer is that because I started my gallery later in life, I decided that it would be a passion project and that I was only going to show what I myself would collect.

I have no judgment for galleries and institutions that do what they do for that bottom line. I’m privileged to be able to sustain a business that supports these artists—with passion. It’s far easier for me—and it’s just who I am as a person—to say “Erica, let me tell you about this piece, and this artist, and what this means…” versus saying “here, buy this because we sell a lot of these.” I recognize that some of the decisions I get to make are decisions that other institutions don’t necessarily get to make.

I’m grateful that I get to do this. I pinch myself that I get to do this. I’m grateful that the artists and collectors that I work with trust me.

You’re right, if I were in New York City, on a busy avenue with huge rents to pay, I may be making different choices. I’m grateful that I’m in the space that I am. My gallery is located in a residential area in Atlanta. We’re a little bit off the beaten path; it’s a destination to get to us. I knew early on that I wouldn’t necessarily expect people to come and find me; I knew that I had to take the work to the people.

And so, I have done pop-ups in Washington, D.C., art fairs in New York, Miami, and Los Angeles. Just trying to make sure we build that network. When I started the gallery almost ten years ago, I knew then that the traditional gallery model was already changing. The sands were shifting—you used to have a storefront where people would come in, see something on the wall, buy it, and take the piece with them when they left. That’s not always the case anymore.

©Kahran and Regis Bethencourt, Sophisticated Soul (2017), courtesy of the artists and Arnika Dawkins Gallery, Atlanta.

EC: How have things changed?

AD: Due to the global pandemic, we’ve pivoted into utilizing online platforms like Artsy. We’ve done virtual viewing rooms, artist talks, and studio visits. The pandemic left us with this new frontier, and it’ll be interesting to see how these avenues continue to evolve to support artists, and to get work out to those who wish to see it. We’ll continue to bolster our website and our social media with ways to interact and have conversations with potential collectors and clients.

EC: Shifting online has certainly been a big trend during the pandemic, and it’s wonderful to see you making use of virtual resources. Seeing how the pandemic has also led some brick-and-mortar art spaces to shut down, I wonder if you think the future of art galleries will end up being primarily in this newfound digital space, or if you are a firm believer in maintaining a physical location.

AD: When I decided to start my gallery, I ended up using a resource that my family and I already had—it’s this little cottage house, inside which the gallery is located. I don’t personally live here, but I think one of the differences of the space is that when people come inside, it kind of demystifies this whole ‘art’ thing. People can imagine art hanging on a wall in their own home.

The nice thing about my set-up is that I don’t have the pressures of monthly rent to contend with. Moving forward, I think we’ll evolve into a hybrid scenario where we do have an impactful footprint in the virtual space, as well as physically here.

I want to be able to meet people where they are—there are still folks who want to see the work up close. There are others who prefer to do commerce online, and who like using digital technologies to, say, superimpose works on their walls. I don’t know where this is all going to end up, but I think it’s a fascinating journey to be a part of. We will try our best to be responsive to our artists, to our collectors, and to larger trends.

Works by Ervin A. Johnson, during a Gallery Collector’s Dinner, courtesy of Arnika Dawkins Gallery, Atlanta.

EC: Who do you have in mind when programming exhibitions? Who do you think of as your audience?

AD: I think of my audience as people who enjoy great art—fine art photography in particular—wherever they are in the world. My gallery specifically specializes in work by African Americans and people from the African diaspora. I thought there was a need to do intentional work in this area—it’s not my exclusivity, but it’s something that really resonates with me, and something that I have a fond interest for.

I find it very compelling that we have collectors who are local, national, and international in scope. This, to me, means that the gallery’s mission fills a need for those who are looking for this kind of work.

EC: I want to acknowledge and underscore your initial statement that what you show is, first and foremost, great art. I feel (and you can correct me if you disagree) that whenever an art space specializes in a particular kind of work—especially work that has not been recognized historically—there is a kind of pigeon-holing effect that happens, where your niche becomes the only thing you can supposedly deal in. It’s crucial for us to recognize the specific work that you and your artists are doing—while also simultaneously framing this work in larger, broader contexts.

AD: I think you’re hitting the nail on the head. As you reiterated, I show, first and foremost, great work by talented artists. I look for work that speaks to me, or makes me feel something, or leads me to reflect on something. I look for work where I am moved or changed for looking. Work that is more than just a pretty, technically proficient picture. I’m interested in the intention that the creator behind the work is conveying to me, the visual dialogue that’s occurring when I look at the work. This is what I hope appeals to and resonates with collectors as well.

EC: How do you find the artists that you represent, and what are your expectations of these artists when you establish a representational relationship?

AD: I think as a gallerist, you’re always looking. It’s like an antenna that’s always up. In particular, I attend portfolio reviews, museum exhibitions, and MFA student exhibitions.

The expectation for a represented artist is that they be professional, and that they be serious about their career and what they have to say with their medium. On my end, I do all that I can to support the artists that I represent. I want them to be fulfilled and comfortable with how we are showing their work. The relationship should be reciprocal—open communication, a commitment to one another. We should both be putting our best foot forward in the partnership, so that the artist’s work can flourish and live on beyond us in museums and collections.

EC: Thinking about the art world as a whole, how do you think art galleries fit in alongside museums, non-profits, etc.?

AD: I think we all play a role in this big—but small!–art world. All of the institutions within our art ecosystem have a hand in supporting creatives and getting artists’ work out there.

I believe that artists are dialed into a different level of sensitivity. While some people pass through the world at a breakneck pace, artists stop and take things in. To have this kind of thinking for future generations is, to me, why we in the art world need to back our artists. The notion of a starving artist didn’t just come out of nowhere—it’s real, and having a support network is crucial for creatives. This includes having people write about art, having historians include pieces in their books, etc. All of this goes together.

EC: Agreed. And I think I’m still trying to make sense of what ‘support’ looks like, especially from a commercial standpoint. When we ascribe high dollar values to artworks, collecting can feel inaccessible to the everyday person—i.e. when a gallery carries a $10,000 work, it’s just out of the realm of possibility for a lot of people. And it’s not until you start thinking more holistically about how that price tag perhaps serves to recuperate the artist’s and gallerist’s time and efforts that you start realizing that maybe there’s more to the valuation than just rampant capitalism.

AD: It’s partly capitalism, right? And it’s humans. Art is not one-size-fits-all. Think about cars—it’s the same. There are cars that are hundreds of thousands of dollars, and there are cars that are fifteen thousand dollars. There’s a range. When you’re at a gallery, I think it’s about trying to buy work that you love.

I remember a couple—I think the husband was a postal worker—that had amassed this crazy massive collection of art through their lifetime… and they lived in a one-bedroom studio! There’s something out there for just about everyone. It’s just how willing or how intentional someone is.

There are the big boys that are dealing in the Basquiats of the world… it’s an interesting dynamic. I think it’s easy to criticize, and there may never be a level playing field.

©Najee Dorsey, Pickles and Peppermint (2020), courtesy of the artist and Arnika Dawkins Gallery, Atlanta.

EC: What’s next?

AD: We will continue to incorporate some of the changes we’ve made during the pandemic into how we exist. We plan to participate in art fairs, which I think will come roaring back. Our next big exhibition will be during Atlanta Celebrates Photography. It’s a pretty amazing opportunity—Atlanta gets very excited about photography! It’s going to be exciting to see how things turn out, and we are looking forward to the possibilities.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Interview with Kate Greene: Photographing What Is UnseenFebruary 20th, 2024

-

Semana Mexicana: Felipe “Chito” TenorioFebruary 5th, 2024

-

Amy Lovera in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 23rd, 2024

-

Michelle Bui: Affinités poreusesDecember 27th, 2023