Jodie Mim Goodnough in Conversation with Douglas Breault

Jodie Mim Goodnough is an artist based in Providence, RI whose work often enlists photographs as a material in sculpture, video, and performance to consider how the history and modern understanding of psychology and psychiatry can become tactile. While the link between mental health and creativity is often romanticized, Goodnough’s thoughtfulness in the nuances of understanding and making apparent the often invisible weight of mental health in a way that is both optimistic and tinged with despair. Her practice isn’t rooted in explicitly translating personal trauma, but rather in shifting the perspective to how mental health has evolved in certain aspects while many stigmas continue to linger in our culture. While art does have the capacity to transform and heal, it also can be a tool to document as evidence of the complicated story of psychiatric institutions.

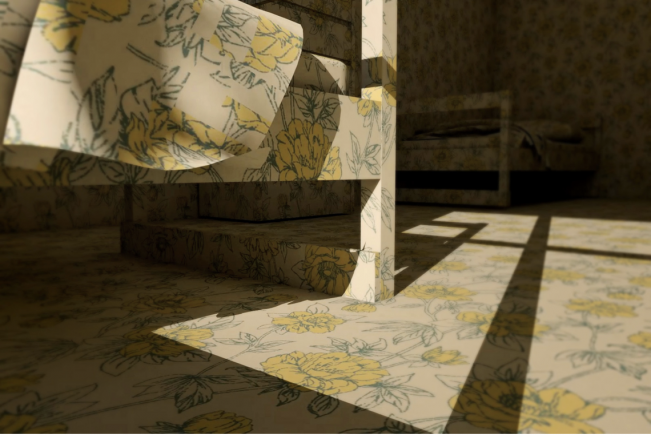

©Jodie Mim Goodnough, “Northampton State Hospital” from Prospect, three inkjet prints on cotton lawn

The series “Prospect” consists of multi-panel photographic images on fabric exploring the idea of the therapeutic landscape as it relates to mental health and the complicated history of the psychiatric institution in the United States. The images are contemporary views from the sites of Victorian-era mental health institutions in the New England area, now the sites of condominiums and townhouses. The eerie spareness from the voided architecture depicted in these installations shifts the focus solely on the delicately draped landscape. The images are a hollow facade standing in for the original hope that window offered. It feels lonely when you position yourself as a contained person gazing outside of the window. The clinical hospital screen immediately causes anxiety in those with white coat syndrome and contrasts the often idealistic landscapes printed on the inexpensive cotton that would have been used for window treatments in the era. The heartbreak of this longing to leave a psychiatric institution is underscored by the fact that many people in those institutions during the Victorian era did not actually require to be institutionalized, like the poor or those experiencing homelessness.

Traditionally, art school attempts to persuade young artists from making artwork directly about events that happen in their life, and Goodnough renders the aftershocks of trauma through nuanced approaches that contain a spirit of stillness. The Yellow Wallpaper, by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, is a short story that enlists an unreliable narrator to describe a woman barricaded by her husband to treat her mental fragility. Goodnough’s body of work with the same title consists of a multimedia collection of works that draws attention to the male-centric healthcare system that continues to negatively affect women, non-binary people, non-white people, and queer populations. The parallels in all of her work provide contemplation of how environmental factors influence one’s well-being and point to the potential for art to translate those intangible experiences. The landscapes incorporated into the installations and sculptures do create a sense of optimism, a new leaf perhaps, that can only be learned from a reflection on the past. Nonetheless, creating and discussing artwork surrounding mental health is necessary to continue to advocate for those who need support and redesign a culture that recognizes the value of mental health support.

A connecting idea through a lot of your work is psychology and memory – how does this process of connecting to psychology and psychiatry influence the decisions you make in your work?

Making work about these topics feels like a constant dance – finding the line between personal but not too personal, universal but not non-specific. I think I’m most interested in how our environment impacts our psychology and vice versa, and how both interact with our physiology. There’s this myth that mind and body are separate, but we know for a fact that they’re not. In some ways my work is trying to pull out the connections between those two things. How do we feel when we look at certain images? How do our bodies react? Can we manipulate that?

This influences the materials I choose more than anything. The softness in my recent works, using fabric and other textiles, has to do with needing emotional softness and care as a society right now, in addition to wanting to work in a way that envelopes the viewer instead of just giving them something to view.

The Yellow Wallpaper is one of the few readings I had in high school that I still vividly recall today. What made you revive this writing piece from 1892 and what context do you think this work has in our current time?

I think a lot about the experience of being a patient, especially as a woman. In 2013 I had a health issue that really highlighted this for me, and then the Covid pandemic and the overturning of Roe V. Wade just increased my frustration with our health care system. The medical concerns of women and LGBTQ people are chronically understudied, and our experiences are questioned. I wanted to make work that engaged with the idea of the unreliable female narrator – The Yellow Wallpaper was perfect for that.

We have both created artwork around the loss of a parent – how has the process of making work instigated by grief and loss affected your practice? Are there approaches or suggestions you have for other artists who are considering how to make work about a loss of a loved one?

I don’t know that it’s affected my practice, but my practice has certainly affected how I process grief. The projects around my family are an important part of the grieving process for me, and I don’t know how I would cope without them. As for advice, I would just say to take your time. You’re a human first, then an artist, and if the work isn’t helping you, you shouldn’t be doing it. It will come when it needs to, if it needs to.

In your work, you often take the photograph off of the wall and turn them into independent objects – doors, curtains, or tents. How does this change how you, or the viewer, reads the image?

Prospect is where I really started to think in this way and began printing on fabric. This allowed the images to move with air currents in the room and helped bring them to life. With the other projects like Threshold and the Forest Therapy Pod, I looked at ways to surround the viewer with the images instead of them existing on only one plane, creating more of an immersive experience. When I went to the museum with my mom as a kid, I was always drawn to large-scale sculpture and installation works – things that would take me out of the moment and transport me somewhere else. It’s definitely something I’m trying to make happen with photography.

©Jodie Mim Goodnough, “Northampton State Hospital from Prospect, installation at Spring/Break Art Show”, 2017, three inkjet prints on cotton lawn

Jodie Mim Goodnough is a Providence, Rhode Island-based artist whose interest in psychology and psychiatry manifests itself through works in photography, sculpture, performance, video and sound. She attended the Salt Institute for Documentary Studies in Portland, Maine and received her MFA from Tufts University in May 2013. Her work has been shown nationally in both solo and group exhibitions, including at Spring/Break Art Show in New York, the Hudson Valley Museum of Contemporary Art and the Newport Art Museum. Goodnough was the recipient of a 2019 Pollock-Krasner Foundation Artist Grant, a 2017 Traveling Fellowship from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, and a 2017 Fellowship in Photography from the Rhode Island State Council for the Arts. Her work has been reviewed in publications such as Art New England and the Boston Globe, and she has attended residencies at ChaNorth, the Wassaic Project, the Byrdcliffe Art Colony and Mass MoCA, among others. Goodnough is currently on the faculty at Salve Regina University in Newport, RI.

Follow Jodie Mim Goodnough on Instagram: @jodie_mim

Douglas Breault is an interdisciplinary artist who overlaps elements of photography, painting, sculpture, and video to merge spaces both real and imagined. His work has been collected, published, and exhibited nationally and internationally, including at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the Czong Institute for Contemporary Art (South Korea), Space Place Gallery (Russia), the Bristol Art Museum, the Rochester Museum of Fine Arts, Amos Eno Gallery, and VSOP Projects. Breault has been an artist in residence at MassMoca and AS220 and was awarded the Montague Travel Grant to study in London and Paris in 2017. Douglas is a professor of art at Babson College and Bridgewater State University, and he has been a guest critic at MassArt, Wellesley College, Kansas City Art Institute, and the Slade College of Art, among others. Douglas is the Exhibitions Director at Gallery 263 in Cambridge, MA. He received his MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University and a BA in Studio Art from Bridgewater State University, and he currently divides his time between Boston, MA, and Providence, RI.

Follow Douglas Breault on Instagram: @dug_bro

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024

-

Artists of Türkiye: Eren SulamaciMarch 27th, 2024

-

Love and Loss in the Cosmos: Valeria Sestua In Conversation with Vicente IsaíasMarch 19th, 2024