The Female Gaze: Suzanne Révy – With Reverence for Light

Diana Nicholette Jeon‘s The Female Gaze has a new home here at Lenscratch and will become a monthly series later this year. It focuses on women photographers and their work as viewed from the gaze and heart of another woman photographer. The Female Gaze alternates between single person interviews and thematic “roundups” featuring multiple women and their work.

Suzanne Révy is a photographer, writer and educator. She earned a BFA in Photography from the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY. After college, she worked as a Photography Editor in magazine publishing at U.S.News & World Report and later at Yankee Magazine. With the arrival of two sons, she left publishing and created a visual photographic diary of their lives. In 2016, she earned her MFA in photography from the New Hampshire Institute of Art (now part of New England College) and more recently has been exploring the wooded landscapes around her home in suburban Boston.

She has exhibited at the Danforth Art Museum, the Newport Art Museum and the Griffin Museum of Photography, among many other regional and national galleries. Révy teaches at Clark University, is the Associate Editor of the online photography review magazine, What Will You Remember? and serves on the board of the Photographic Resource Center in Cambridge, MA.

It’s often easy to take a cursory look at a landscape photo and move on, considering it yet another pretty picture and not much else. But I beg you not to do that with the landscape work of Suzanne Révy. There is an elegance and thoughtfulness in her making of the images that rewards the viewer who stays beyond first glance. First, the color palette and the attendant fog and mist are tied to the specific times of day, sunrise and dusk, when she makes photographs. Then, with the diptychs and triptychs, she carefully considers where the images split and overlap. There’s a message in these disruptions of the land. Finally, whether the photograph is of her children, a stray shopping cart, or the lands where Thoreau roamed or the first battles of the American Revolution were fought, you get the sense that she has a fond reverence for the subject matter and the light. It is subtle but noticeable, which gives Révy’s work that je ne sais quoi, making it stand out as unique and unmistakably Révy’s.

I invited Révy to be my first interviewee for The Female Gaze in its new home. I hope you enjoy our conversation as much as I did.

Tell us about your childhood.

I grew up in Los Angeles and had a relatively happy early childhood. My father was born in Switzerland, so we spent many summers there visiting family and lived there for two years when I was a teenager. I was a sensitive kid and struggled with schoolwork. Hindsight being 20/20, I realize now that I had some issues with ADD and Dyslexia, but I was also frustrated that I found it difficult to draw. I was envious of my mother’s ability to sketch and paint; it seemed to flow through her fingers! But she took us to many museums, and collected a lot of art books, so I was introduced to all manner of art early in my life.

What brought you to photography?

My parents were avid snapshot shooters, so we always had a camera on hand. Around the time I was fifteen, I became interested in photography, and my dad gave me a Nikkormat camera. I still have it, but it’s jammed up!

Around that time, my mom was also learning how to print, and she built a darkroom in the closet of a studio space she had. I took a “mini-course” in photography at my high school; it was the only photo class offered. I remember my first assignment, to photograph a vegetable! I found a wilted head of lettuce at the back of the fridge and proceeded to expose an entire 36-exposure roll of Tri-X, placing it in locations all over the house. I was hooked!

What did you major in at Pratt?

I left to study photography at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn long before it was hip to live there! It was a classic art education starting with a foundation year of Drawing, Light Color & Design, and Form in Space. I finally learned to draw—I found that it could be mastered, and it was one of the more valuable classes for honing my observational skills.

I continue to be influenced by and still think about the photo teachers I had there. Phil Perkis was the Chair of Photography, and I studied with Bill Gedney, Ann Mandelbaum, Judy Linn, Christine Osinski (who I also studied with later for my MFA), and Paul McDonough, among others.

In addition, I studied a great deal of Art History, which has informed my visual language.

©Suzanne Révy, Bench, Minuteman National Park, Concord, MA from the series A Murmur in the Trees (2020)

What was a typical day like as a photo editor? Was it significantly different at Yankee than at a news magazine?

It would depend on the day. While working at U.S. News & World Report, I generally worked at the “back of the book,” which included the business, culture, ideas, science, or consumer sections. Our deadlines were earlier in the week, so I typically had to show pictures to the art department, the writers, editors, and the Director of Photography by Monday, Tuesday, or Wednesday and file the captions. Then, we would start laying out the pages while planning the following week’s issue. Sometimes, I would have to do a little pinch-hitting for the breaking news sections as the week wore on. Thursday was generally the busiest day of the week. There is a real art to making assignments, finding the right photographer for the job, culling the pictures and crafting a sequence to tell a specific story. A good photography editor’s hand is invisible.

My time at Yankee magazine was more relaxed. I did not have such tight deadlines as it was a monthly magazine, but I worked on about a year’s worth of issues, so I was assigning stories a year before they would be published. I remember a big story on Providence that we planned. I had the luxury of going there to scout locations ahead of time, meet with some of the people we interviewed and would photograph, and discuss our needs with the photographer. Having such a luxurious timeframe to develop longer-form picture stories was great.

I was filling in for a Picture Editor who took a leave of absence for six months, so when the job ended, I decided to take a year and determine my next move. Happily, I became pregnant and was fortunate to do the mom thing, which led me back to my photography practice, rekindling my interest in black-and-white photography.

What prompted you to return to school for an MFA after working and raising a family? Was it challenging to do that?

Getting my MFA was a bucket list item, and my main goal was personal enrichment, though it has opened a few doors to teaching. I found a low residency program that allowed me to pursue the degree while navigating those rocky teenage years with my sons. My kids were in middle and high school, so I was able to complete the third of three chapters in a long-term documentary project on them. It was a lot of work, but the program had a strong writing component, which has become an invaluable part of my artistic practice.

And though it was embryonic, I began to make pictures in the landscape during that time. I was unsure where I might take it, but the seed was planted!

Where do the ideas you work with come from? Can you share your approach to creating the work? What do you do when encountering a period of creative block—how do you work through it?

At the end of the day, I do not have any ideas, but I make pictures daily to find some.

When I feel blocked, it generally coincides with one project coming to a conclusion and then floundering around for what might be next. For example, the year after I finished the MFA in 2016, I made very little work. I worried my best work was behind me; between a backlog of film to scan and starting to teach, I could not concentrate on new work. But I still wanted to keep my eyes working, so I began making daily (or almost) daily pictures with a smartphone camera. It became an easy habit and functioned like a musician practicing scales.

Could you discuss the transition from years of photographing your children to your recent focus on landscapes (famous ones, at that.)

As I mentioned above, I began to make pictures with my phone while I worked through a backlog of films. The project with my kids was coming to a close, and I was still figuring out what I should do next. The phone pictures were quick and easy and eventually became a smal portfolio I called A Certain Slant of Light because my mantra had been to find some interesting light somewhere each day. I printed several as dye transfer on aluminum, mimicking a backlit screen’s luminosity. I showed them installed in a grid-like manner. That made me think about how to make a single piece of art with more than one print.

Around the same time in 2018, I began experimenting with diptychs and triptychs of pictures of my younger son in the landscape. He was still home while my older son was off at college. Eventually, our younger son left for college, and I just started playing around with the landscapes, making triptychs. It took me a while to figure out how to make them work through trial and error. There are a lot of failures!

I had planned to go to California for several weeks in 2020 but was upended by the pandemic. Instead, I photographed in Concord, MA, close to my home. (Most of my landscapes are ten to twenty minutes from my house!) I was looking for quiet, lesser-known conservation areas that were not too busy. I’d head out at dawn to make pictures, meditating in the early morning air, just me and the camera. Occasionally, I’d startle a deer! This work flourished through the pandemic.

You spend a lot of time writing about the work of other photographers. Does that influence your work at some level?

I do learn a lot from writing about others. It can be particularly eye-opening when I don’t really like work, but once I give it a lot of thought, I will come around to it. My goal when writing about others’ work is to understand it at a more profound level. I also tell my students to pay attention to imagery they do not like because they might learn something about themselves and their motives. And my students are a source of inspiration for me, particularly the ones who push themselves.

It seems like one of the great battles in photography is between those who think their work should speak for them and hence don’t write and those who believe writing can offer an entry to the work to viewers who don’t find one as well as underscore the artist’s ideas for viewers who did. Besides writing about your own and others’ work, you also teach workshops (with Elin Spring) to help artists clarify their writing. What is the most important thing someone should do/say in writing about their work?

Keep it clear, keep it concise, and keep it conversational. It is good practice to have a bio, project, and/or artist statements that you can adapt and edit as needed, particularly if submitting to juried calls or being invited to an exhibition. I know it’s a pain for many, but it can clarify your thinking and help you discuss or articulate your work with viewers, curators, or gallerists. You should not analyze it; instead, offer a sense of your motivation, intention, or inspiration. It can provide an entry point for viewers to more fully experience the scope of your work while allowing them the space to bring their own experience or interpretation to it.

How do you balance teaching, writing/reviewing, and making work?

That comes down to keeping track of my schedule each week. Photographing is easy; I generally do it early in the morning or late in the day. And then writing, teaching, and scanning happen when the light is not great outside.

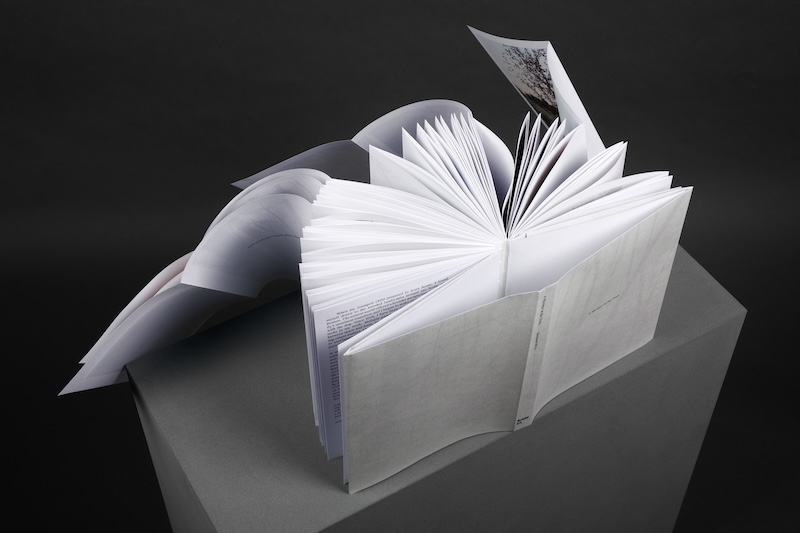

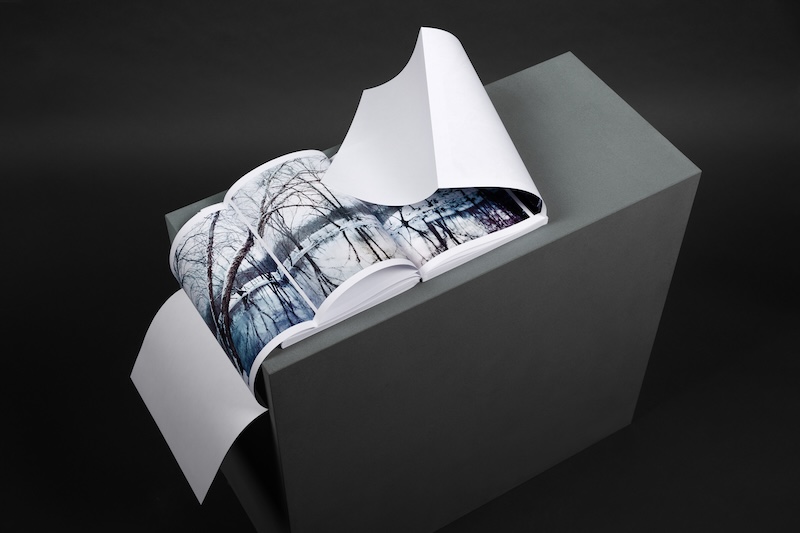

©Suzanne Révy, A Murmur in the Trees photo book. Photo Credit: book documentation by The Book Photographer (Instagram: @the_bookphotographer)

I’m jealous of your book! It’s just gorgeous. The people you worked with to bring A Murmur in the Trees to life are among the best in the industry for creating art and photo books that underscore the concepts inherent in an artist’s project. Could you talk about the book and what the process was like for you?

I knew for about a year and a half that I would be exhibiting at the Danforth Museum of Art. Exhibitions are tremendous but ephemeral— books can be enjoyed for years. So, I thought it was time for me to publish a book.

I reached out to Caleb Cain Marcus of Luminosity Lab after seeing him present at a panel hosted by the Griffin Museum of Photography. We had several detailed phone conversations about the work and my ideas for the book, and then he was in New England for another event and came to my studio to discuss a sequence. We looked at a few books I had on hand and talked about what we liked and did not like about them. That gave us both ideas for a direction for the book, and we came up with a sequence. Caleb then developed a folding scheme that allowed for sentence fragments from Thoreau to accompany the pictures without appearing together. Workshop Arts is a small imprint Caleb started, so I just decided to have them publish the book. He knew the work and the thinking behind the design, and I wanted a publisher so I would not be the only one selling the book!

We opted for a simple paper cover to encourage a slower, more deliberate pace in looking at a book. One person told me they open a new gatefold daily and display the book on a table. I love that. Caleb did the legwork with the printers and the binders, and I was “on press” when it was printed.

It may not have been necessary, but I believed writing would offer context and deepen the viewer’s experience. Through a book of essays on Thoreau, Now Comes Clear Sailing, I discovered a poet, writer, and Thoreau scholar named Kristen Case, who penned a beautiful essay that articulated several Thoreauvian ideas inherent in my pictures.

Detail 1: ©Suzanne Révy, A Murmur in the Trees photo book. Photo Credit: book documentation by The Book Photographer (Instagram: @the_bookphotographer)

The battle for women photographers and artists to have equal recognition is still ongoing in the art world. Museums still hold more works by men, and the more well-known galleries are still showing more men’s work more than they show than women’s. It was improving, but very slowly. However, given the current administration’s ideas of women’s roles, that progress is being erased. As an ex-editor, current photographer, educator, and arts writer, do you have any thoughts about this?

That is a big question! I am beyond frustrated with museums and galleries emphasizing one demographic, generally white heterosexual men. Art should reflect our culture and society, but there are gaping holes in the canon because of this issue. And never mind if you are a mother—talk about the kiss of death to a blue-chip art career.

At the moment, it is an uphill struggle to continue to find, show, and engage with all manner of voices, notably because of attacks on higher education, the arts, and women’s rights. It has been utterly deflating, particularly since the election last year.

Outside of the big institutions, however, there is a vibrant world of art that is more welcoming to a diverse swath of artists and photographers. The smaller, non-profit arts incubators and spaces offer thriving communities to make connections and show and share artwork. Eventually, artists who take advantage of these smaller venues and organizations might develop work that could find its way onto museum walls and collections. Persistence…

Detail 2: ©Suzanne Révy, A Murmur in the Trees photo book. Photo Credit: book documentation by The Book Photographer (Instagram: @the_bookphotographer)

What is influencing your work now, and what’s coming on the horizon for you?

Over the past three years, I have photographed a small, fetid pond on our street at dawn with a smartphone camera. Lately, I have expanded on that, photographing it with film, including Polaroid instant cameras, and I’m planning to add Holga camera work into the mix. There are a couple of adjacent fields, one of which has apple trees, that I have been photographing during early morning walks. It may be a bridge to a new, more complex project. We’ll see…

I will also spend a month this summer photographing an ancestral family home and garden in Switzerland, something I have wanted to do for some time.

Finally, this spring, I am participating in a large collaborative project on the Charles River organized by Lisa McCarty, who teaches at Northeastern University.

Thank you ever so much, Suzanne, for your thoughtful responses to my questions. It’s been really fascinating to have this discussion and learn more about your and your practice. I look forward to seeing how your work continues to evolve!

Readers, I hope you enjoyed learning about Revy’s work. More information on her book, A Murmur in the Trees, (©Suzanne Révy, with additional text by Kristen Case. Designed by Caleb Cain Marcus, Luminosity Lab) is available here.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Aaron Rothman: The SierraDecember 18th, 2025

-

Photographers on Photographers: Congyu Liu in Conversation with Vân-Nhi NguyễnDecember 8th, 2025

-

Linda Foard Roberts: LamentNovember 25th, 2025

-

Arnold Newman Prize: C. Rose Smith: Scenes of Self: Redressing PatriarchyNovember 24th, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025