Photographers on Photographers: Christa Bowden on Binh Danh

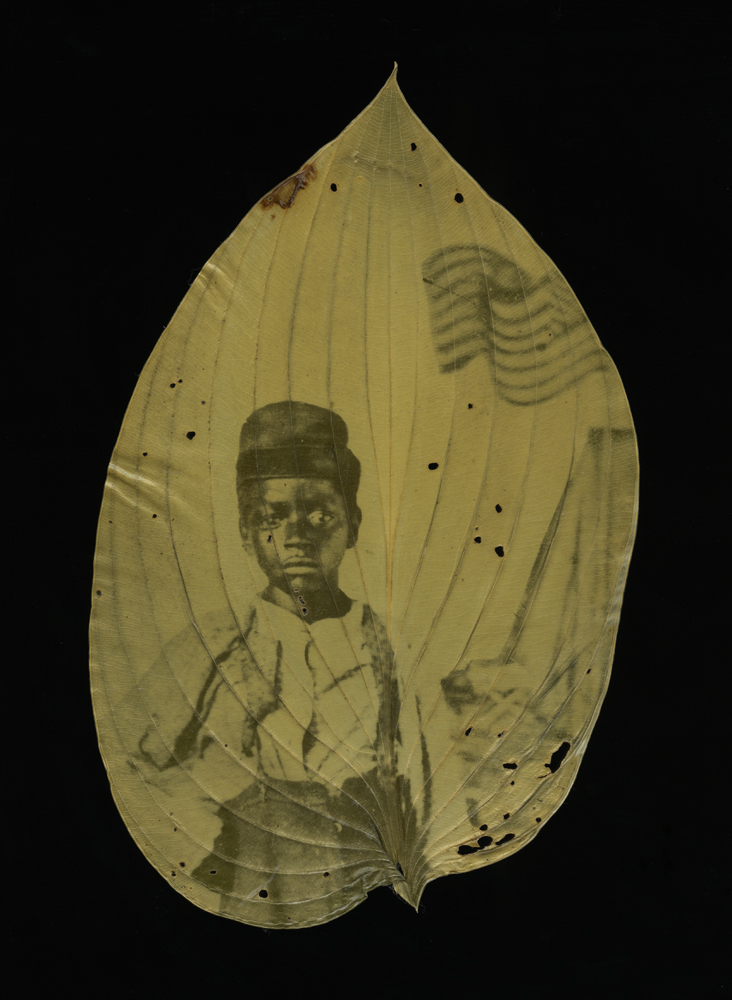

©Binh Danh & Robert Schultz Unidentified African-American boy and flag chlorophyll print and resin 14.5 x 11.5 inches 2012

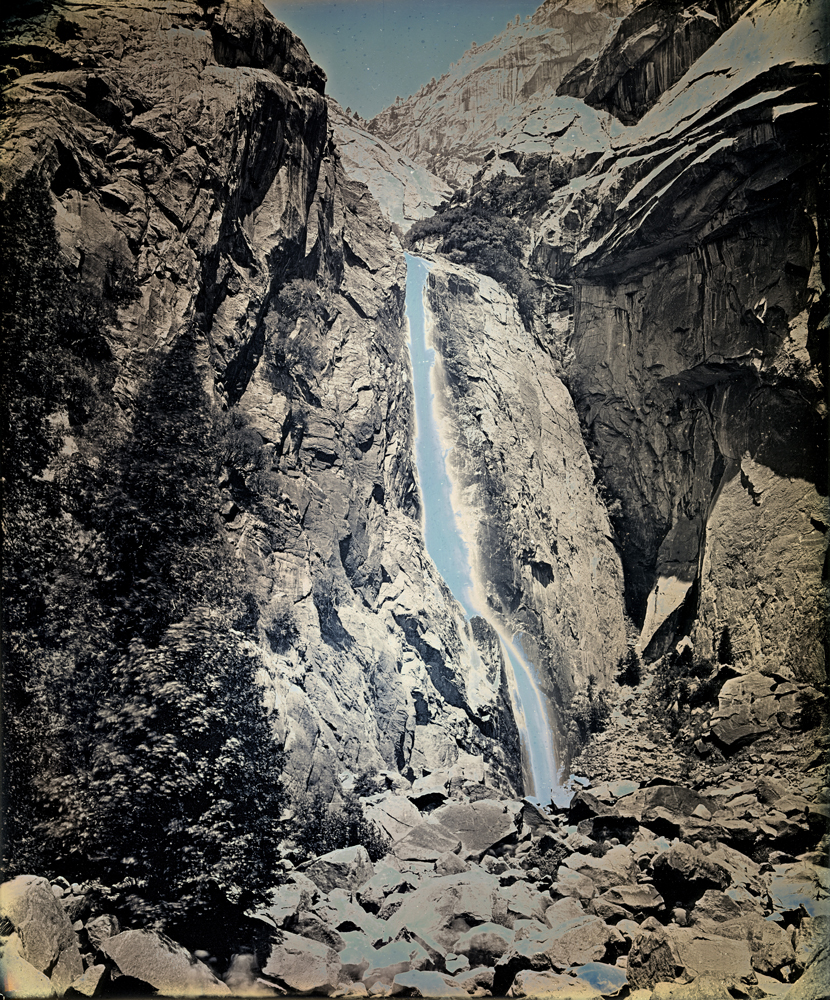

I first met Binh Danh in 2009 when he was an artist-in-residence at Hollins University, near where I live in Virginia. I was already aware of his development of the chlorophyll process for printing photographs on leaves, and the importance of this contribution to the canon of alternative photographic processes. I also held a deep admiration for Binh’s photographic exploration of war and memory in relation to his native Vietnam. Binh has returned to Virginia many times over the past decade, and over the years we have become good friends. On one of these return trips, he showed me the daguerreotypes that he was making of Yosemite National Park. Although the spectacular views were very familiar, they were somehow completely transformed through Binh’s process and interpretation. This was a cathartic moment for me, seeing how he could take a well-known and famously photographed national park and reinterpret the landscape in a way that was completely new. This, in part, inspired me to begin my own project photographing Cumberland Island National Seashore, a national park that for me, like Yosemite for Binh Danh, holds deep personal significance.

Christa Bowden was born in Atlanta, Georgia and holds an MFA in photography from the University of Georgia and a BA from Tulane University. She is a Professor of Art at Washington and Lee University, where she started the photography program in 2006. She has been the recipient of a Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Fellowship and a nominee for the Santa Fe Prize for Photography. Over the past twenty years her work has primarily explored the use of a flatbed scanner as a camera and the utilization of natural objects as personal metaphor. She is currently working on a multi-year collaborative project on Cumberland Island National Seashore with photographer Emily J. Gómez and multi-media artist Ernesto Gómez. She lives in Lexington, Virginia.

Christa Bowden was born in Atlanta, Georgia and holds an MFA in photography from the University of Georgia and a BA from Tulane University. She is a Professor of Art at Washington and Lee University, where she started the photography program in 2006. She has been the recipient of a Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Fellowship and a nominee for the Santa Fe Prize for Photography. Over the past twenty years her work has primarily explored the use of a flatbed scanner as a camera and the utilization of natural objects as personal metaphor. She is currently working on a multi-year collaborative project on Cumberland Island National Seashore with photographer Emily J. Gómez and multi-media artist Ernesto Gómez. She lives in Lexington, Virginia.

Binh Danh (MFA Stanford; BFA San Jose State University) emerged as an artist of national importance with work that investigates his Vietnamese heritage and our collective memory of war – work that deals with “mortality, memory, history, landscape, justice, evidence, and spirituality.” His technique incorporates his invention of the chlorophyll printing process, in which photographic images appear embedded in leaves through the action of photosynthesis. His newer body of work focuses on nineteenth-century photographic processes, applying them in an investigation of battlefield landscapes and contemporary memorials. A recent series of daguerreotypes celebrated the United States National Park system during its anniversary year. His work is in the permanent collections of the National Gallery of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The DeYoung Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the George Eastman Museum, and many others. In 2012 he was a featured artist at the 18th Biennale of Sydney in Australia. He lives and works in San Jose, CA and teaches photography at San Jose State University. www.scenicdags.com

Christa Bowden: How did you initially discover and learn the medium of photography?

Binh Danh: Photography came to me at an early age. One of the most profound childhood memories I have is that of a class camping trip during the fifth grade. It was the first time I was away from home, so naturally, I was nervous and excited to venture into the wilderness. My father bought me a camera for this extraordinary occasion. When we arrived at the campground, the first thing I did, even before exiting the bus, was to pull out my camera and snap a photograph through the foggy bus window. I did not know that this was the start of my life as a photographer. I still have these pictures today, and every time I look at them, I am transported back to my childhood, trying to make sense of my life through the lens of a camera. I did not become conscious of photography as an art form until high school, where I fell in love with a photo art class. With all the angst that came with being a teenager, I found my outlet in working in the darkroom during lunchtimes. I knew at that moment that I want to make a life with photography.

CB: How have your experiences as a Vietnamese-American and your relationship to Vietnam, both fleeing with your family as a refugee when you were a baby, and then returning when you were in your twenties, influenced your work as an artist?

BD: My personal history has affected my art tremendously. When I was growing up, what I knew of Vietnam was a country torn apart by war. Those pictures of the Vietnam War had a profound effect on me. Seeing pictures of suffering and death, reminded me that my parents did not want to raise a family in a war-torn country, so they planned to escape, but that plan was delayed when I was born in October of 1977. But in August of the following year, we left the country as “boat people,” the term given to the method of our exit.

Since we left with only the essentials to survive a week on a fishing boat with about 50 other refugees, taking the photo albums was not necessary. Growing up, I knew I was born in Vietnam, but there were no pictures of my family in Vietnam. And the only baby pictures of me were refugee ID photos. In 1999, I returned to Vietnam for the first time and met my grandmother, who showed me pictures of my family and me. She said that for a year, she did not know if we survived, and the pictures were what she had to remember us. This trip for me opened my eyes and ears to Vietnam as a country and not a war. I also witnessed how the “imprint” of war became part of life. For example, I learned that many of the bomb craters had been converted into rice paddies. The locals said that rice paddies don’t need to be square. I also came across many military tanks sitting in the land, rusting. The United States military left a lot of war debris in the land if they were not able to destroy them or burn any documents. There was footage of helicopters being dumped into the sea. My father told me that after the war, he took the freezers left by the US military, to make ice cubes for a living. When I returned to the US, the Vietnam war haunted me, as it did growing up as a Vietnamese-American, when my parents would take my siblings and me to anti-communism rallies to witness the burning of effigies of Ho Chi Minh. The war was painful for all sides, Americans, Vietnamese, and Vietnamese-Americans. As an art student, I was brainstorming how could I represent this, that there were no winners in this war and the commonality for me was death. How do I represent death? But also give death, not an ending but a continuing beginning, a full circle, so that was when the idea of printing on leaves came to me as I was standing there in my mother’s garden.

CB: You are also a photo educator. How does your role as a teacher impact your work as an artist?

BD: It impacts me very much so. When I was in grade school, I always looked up to my teachers. They cared about education, especially in the arts. In high school, I fell in love with art making because I had such great art teachers. In high school photo classes, my photo teachers, once figuring out that photography was becoming second nature to me, gave me the chore of helping out the other students. There was this sense of reward when my classmates and I figured out the photo problem, whatever the assignments were.

Teaching is about communication and community. Today I view my artwork doing the communicating with a community (the classroom), but rather in words, in visual, and the sense of gratification that comes when a viewer gets the work, like how a student would get a concept, and that concept carries onward in one’s life. When I’m in the studio, I keep my teaching hat on, as I am trying to teach myself by making art. When I am in the classroom, I don’t take off my artist’s hat because I have to think on my feet as like when I am making art. It’s one continuous stream if I am making art by myself or helping an art student make artwork. It’s about the process of learning together around the subject of art making.

Binh Danh & Robert Schultz Walt Whitman, 1887, in Camden House hosta leaf chlorophyll print and resin 14.5 x 11.5 inches 2011

CB: You are known for your invention of the chlorophyll process. Can you talk a little bit about the process and how that discovery happened for you?

BD: It was one of those aha moments; the ones that make sense and give life to creativity. It’s just a what if, as I remember it, what if this, what if that. Questions artists ask for themselves all the time in the studio. What if I put red next to pink? In this case, what if I could place an image onto a leaf? Is that even possible? And why? What’s going to happen? What am I trying to say? Let me see if it is possible.

Like any darkroom work and trial and error, I figured out a way to expose an image onto a leaf. The process is much simpler than it looks. It’s really an “alternative” to the alternative process, as we all called it today, of the Sir John Herschel’s Anthotype process, where rose petals and blueberries are ground up and reduced into a light-sensitive concoction, then coated onto a sheet of writing paper, and exposed in a contact-printing-frame with an etching (used as a negative in Herschel’s time) on top of the light-sensitive paper. The sun’s UV light would “bleach” away the pigment leaving a positive image from the etching. This process is working the same way with a freshly plucked leaf. The leaf is the light-sensitive sheet of paper, and the engraving is substituted with an image on a transparency. I did not make the Anthotype connection until I read about that process in a photo history book. There were many different photographic processes in the 19th century. Today we only remember a few of them, and even fewer are in practice.

CB: What brought you to the daguerreotype process? How does this process tie into the content of the projects that you have used it for?

BD: The daguerreotype is considered the mother lode of alternative processes because of the cost, time, and the mystery of the process. And being one of the first, it is considered one of the most permanent, but also one of the most fragile since the image could be wiped off or the silver plate could oxidize if it is not sealed airtight. After several years of working with the chlorophyll printing process, I became known as the leaf guy, and wanted to explore other methods and the content they hold. Naturally, the daguerreotype was the one that I gravitated towards, since the process itself was mysterious, and the image quality of a daguerreotype is like no other photographic print. And actually, it is not a print, but a plate, a one of a kind image on a silver plate that was loaded into the camera, exposed, developed, and as most did in the 19th century, gilded with a solution of gold chloride to make the plate more stabilized by protecting it under a layer of gold.

In the 19th century, it was known as a mirror with a memory, a mirror held up to your face which remembers your likeness. And as a mirrored object, when viewed, it reflects the person doing the looking, and they become part of the artwork. I love everything about how this process looks. It is also incredibly detailed, and being a first-generation image, it is one of a kind. The grains, if there are grains, to the daguerreotype image are made of microscopic, almost nano, silver crystal. The image is grown with silver crystal. How beautiful is that, how royal? It is this reflection “play” that I want to capture in the making of the work as well as the viewing of it. When I am polishing plate, I spend the whole day in the studio looking at myself, almost narcissistically, but I am dreaming of what image this plate would hold, what scene it would preserve, and what hour it would record, and be a future relic.

CB: Although you are from California, various opportunities have brought you to Virginia, and specifically to the Shenandoah and Roanoke Valleys, a number of times over the years. Can you tell us about the experience of making work in this place, which is so different both in terms of landscape and memory from your home on the west coast?

BD: I first came to the Virginia area in 2006, when my work was part of the exhibition “The Genius of the Place: Land and Identity in Contemporary Art” at what was, at the time, the Art Museum of Western Virginia, now the Taubman Museum of Art. And just like being in Vietnam, I was taken by the fertile and lush landscape of the south. The wetness of the summer humidity and the fireflies I encountered were, I would say, an engagement with nature. When I was living in Lexington in 2009, I recalled every so often dumping the water from the dehumidifier onto the tomato vines and enjoying the thought that all is connected to air, water, and soil.

Virginia was also where I discovered the work of Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” with the help of Robert Schultz, who at the time was an English professor at Roanoke College. He is now retired, and is producing quite fantastic chlorophyll prints in his backyard. For years, we worked on a project for the Taubman Museum called “War Memoranda,” which will be traveling to The Phillips Museum of Art at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, PA this fall. Bob and I explored the Virginian landscape, the once Civil War battlefields, and the effort of Whitman to record the effect of the war on his poetry. We relate this project to the current conflict in the Middle East and the battle between the North and South Vietnam. Virginia was and is a spectacular landscape. One could smell the history of the land. And coming from California, I don’t often contemplate the American Civil War. So, after 2009, when I returned to California, I started to view the landscape with fresh eyes. I was not confined to the Silicon Valley and realized green spaces just a drive away. That’s when I had the idea of mastering the daguerreotype process and taking it on the road to Yosemite.

CB: Why did you decide to create a project about Yosemite National Park? Did you have a specific interest in that park, or in national parks more generally?

BD: So, the Yosemite work came because I had an interest in Ansel Adams. I think most photographers came to photography because of viewing Adams’ work, at least the ones on the West coast, who were also influenced by the f/64 photo club, which included the work of Adams, Imogen Cunningham, and Edward Weston, among others. I had an interest in Adams’ Yosemite photos. As a kid, viewing those images was a way for me to escape the boredom of working in my father’s TV repair shop. I wanted to be Ansel Adams and make pictures like Adams, but of course, there was only one Adams and no need to repeat what he had already done. One can’t compare themselves to Adams. He is a photo god!

I was thinking that with the daguerreotype process or “vision,” I could escape Adams’ train stop and set out on making something new about sites in the Yosemite Valley. Later, in an article, I was surprised to read that Adams had compared his photographic prints to the quality of 19th-century daguerreotypes to see if he had hit the right musical scale. I was stunned when I came across the idea that Adams considered the characteristic of a well-made daguerreotype as the ultimate gauge when he was contemplating his photographic skill, how beautiful things go full circle.

From August of 2001 to January 2002, The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art mounted an exhibition of Adams’ prints called “Ansel Adams at 100,” to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Adams, and organized by guest curator John Szarkowski. I happened to view the exhibition after September 11, and being naïve and not understanding the concept of an anniversary, I thought that Adams was still living at 100 years old. But after realizing it was an anniversary, I wondered what Ansel Adams would have thought about 9/11.

CB: Yosemite is, of course, one of the most famously photographed national parks. How did you approach the challenge of creating something new with such a well-known photographic subject, and also in terms of landscape photography more generally?

BD: When the daguerreotype process was introduced to the world, it became a way to record faces, portraiture work, and even painters feared that their livelihood was going to be replaced by the much quicker, more affordable, and democratic medium called photography. Being a daguerreotypist in the 19th century was a business. There were only a handful of daguerreotypists who would consider their plates as works of fine art, like those by the Bostonian team of Southworth & Hawes. But many of them, including Southworth & Hawes, had to use this process to make a living doing commissions, mostly in the form of portraiture.

Today, I want to use this process in my work as a landscape photographer, as this territory was not explored with the daguerreotype. Landscape photography came later, mostly in the form of wet-plate, when the majority of the photo economy switched over the paper photography and negative based capturing, first in paper negatives, calotypes, and then glass plate negatives, and for most of the 20th-century, film photography. Landscape photography with the daguerreotype process is new, modern, not 19th-century, and I would argue 21st-century.

CB: Which other national parks have you photographed besides Yosemite?

BD: I have been to many more national parks, such as Death Valley, Arches, Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, Joshua Tree, Saguaros, and Sequoias, as well as National Historic sites, like Manzanar, where during the second world war, Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans were kept as prisoners. Ansel Adams and Dorthea Lange made most of the documentary photographs that came from this encampment. Trinity Site at the White Sands National Monument in New Mexico was where the first atomic bomb was detonated. Today the NPS commemorates this location with an obelisk that marked the center of the explosion.

CB: It is really interesting how, in some of your images, you are capturing visitors’ experience of the parks through the daguerreotype. It creates a slowed-down sense of time that makes it feel cinematic.

BD: Indeed. Most of the time, people disappear from the long exposure. When they do appear, it’s quite magical. From the image, we could really sense time being recorded. Also, most iconic 20th-century photographs of the National Parks exclude the visitors. In my 21-century daguerreotypes, I’m interested in how the visitors fit into the park. How having them there completes the park as an experience rather than just a “fixed” image, no pun intended.

What also fascinated me, due to the lengthened exposure is the “visibility” of wind. You could sense that in the trees and waterfalls. Wind is quite an issue, especially with large format cameras. Wind could be blowing while I’m exposing, at times ruining my exposure because the camera and tripod would be shaking and the result would be blurry. The 19th-century photographer Carleton Watkins would shoot with his mammoth camera, 18 x 22 wet glass plate, in the morning and then switch his camera to the stereoview smaller version in the afternoon when the wind picked up. And we forget that Victorian photographers believed that the direction of the wind affected exposure times. A common saying, “When the wind is in the East, double the exposure at the least.” And that was somewhat true as the wind from the smoke and pollution from London would eclipse the sun and needed UV light of these early processes. Today, with our quick digital cameras that could shoot at 1/8000 of a second, we are not in tune with the wind. It’s quite neat that during my long exposure, it’s meditative, I feel both the wind and time elapsing. That moment of exposure is when I rest and view the scene. A sense of vulnerability comes through me.

CB: Are there any new projects that you have in the works that you would like to tell us about?

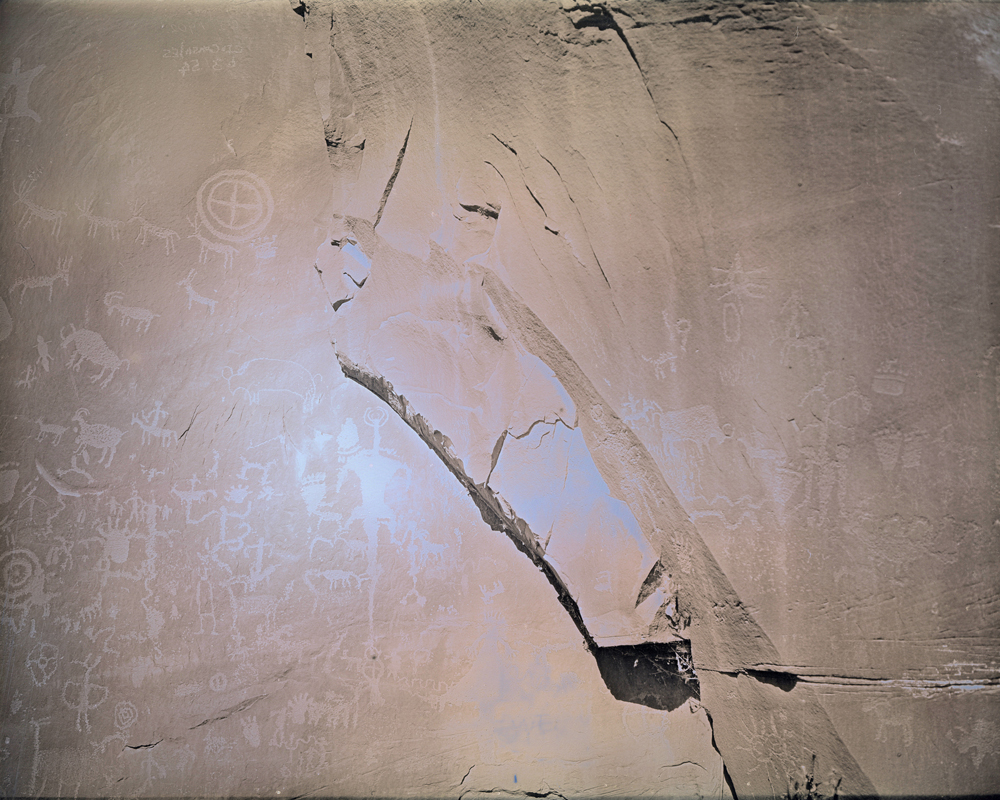

BD: I enjoy this question, but at times fear answering it. Yes, I always have new work in the studio, but they’re quite old photographs or ongoing projects that I have been working on for several years and haven’t been able to put together as a series. Most of them are daguerreotypes of here and there, and they might come together someday as a series. For example, I have been daguerreotyping petroglyphs in the Southwest, where I was living for the past six years. These spiritual cravings onto rocks and walls are quite impressed that even the daguerreotype plates couldn’t reveal its, I would say, energy, the hand of the past touching stone and contemplating existing.

These plates might go well with my Spiral Jetty daguerreotypes of one man’s attempt to put his marking on the land, ha. Either way, it’s humankind asking if I would be remembered. I have a project in-progress in New Orleans with the Vietnamese American communities and gardens, which is about resilience. How does a community come together after the war and after Hurricane Katrina, and other disasters like the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010? This project will be shown at the Louisiana State Museum at the Cabildo this December.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ragne Kristine Sigmond: Portraits of Painterly LightDecember 2nd, 2025

-

Mary Pat Reeve: Illuminating the NightDecember 1st, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

MATERNAL LEGACIES: OUR MOTHERS OURSELVES EXHIBITIONNovember 20th, 2025