One Year Later: Nykelle DeVivo

Over the next three days, Drew Leventhal, the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Winner, interviews the Top 3 Lenscratch Student Prize Winners of 2023. He shares a conversation today with Nykelle Divivo.

Nykelle Devivo’s pictures have an unmistakable energy to them. The images crackle with the desire to connect to the past and the future. As we talk about below, Nykelle has long been inspired by the Japanese photographers that surrounded Provoke magazine in mid-20th century Japan. The grainy contrasty images that result from that influence intentionally disorient us, forcing us to search the shadows for clues. These are pictures that speak with their full voice, that refuse to be ignored.

This was my first time speaking with Nykelle and it was a joyous event. They were unafraid to explore the deep complexities and beauties of their work. The best interviews are the ones that feel more like conversations or a brainstorming session. This was one of those instances and I came away from our time together with a new respect and love for photography. -Drew Leventhal

Nykelle DeVivo is a Southern California visual artist working with light through various mediums to navigate the crossroads between the physical world and that of their ancestors. They studied theory & photography at the San Francisco Art Institute before becoming an inaugural Google Image Equity Fellow, internationally exhibiting their work and having their photographs acquired by permanent museum collections across the country. Nykelle is currently working on publishing their first monograph while pursuing their MFA in visual art from the University of California San Diego, where they expect to graduate in 2025.

Follow Nykelle DeVivo on Instagram

Tha Crossroads

(2013-2023)

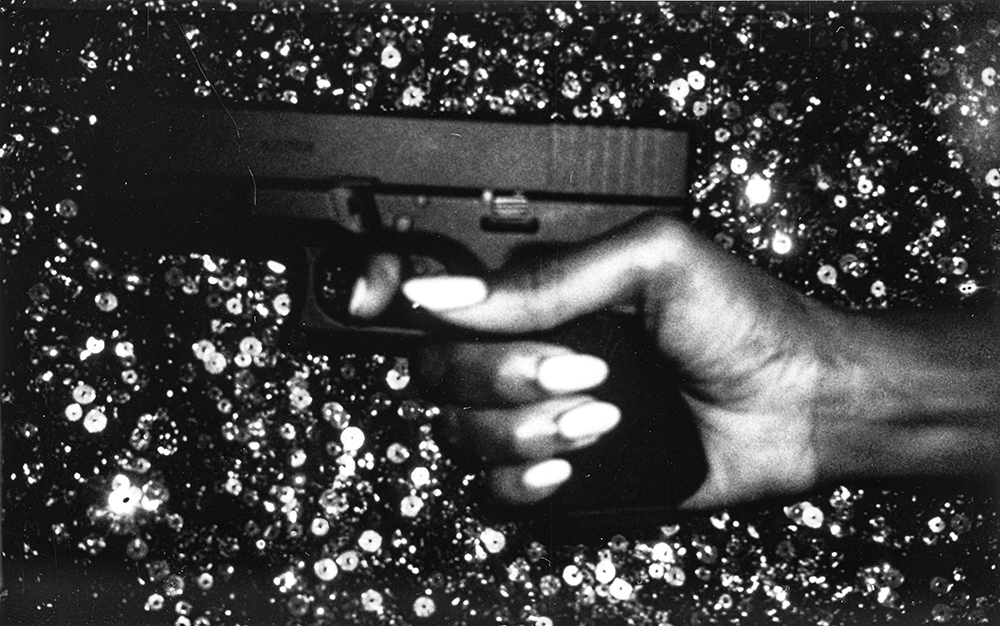

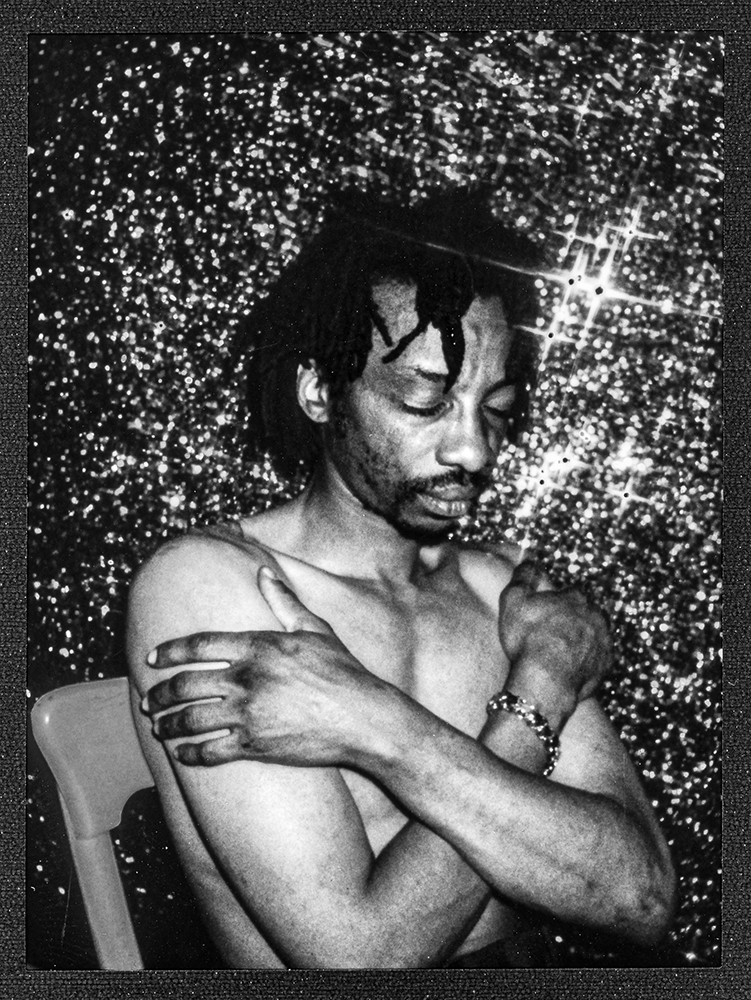

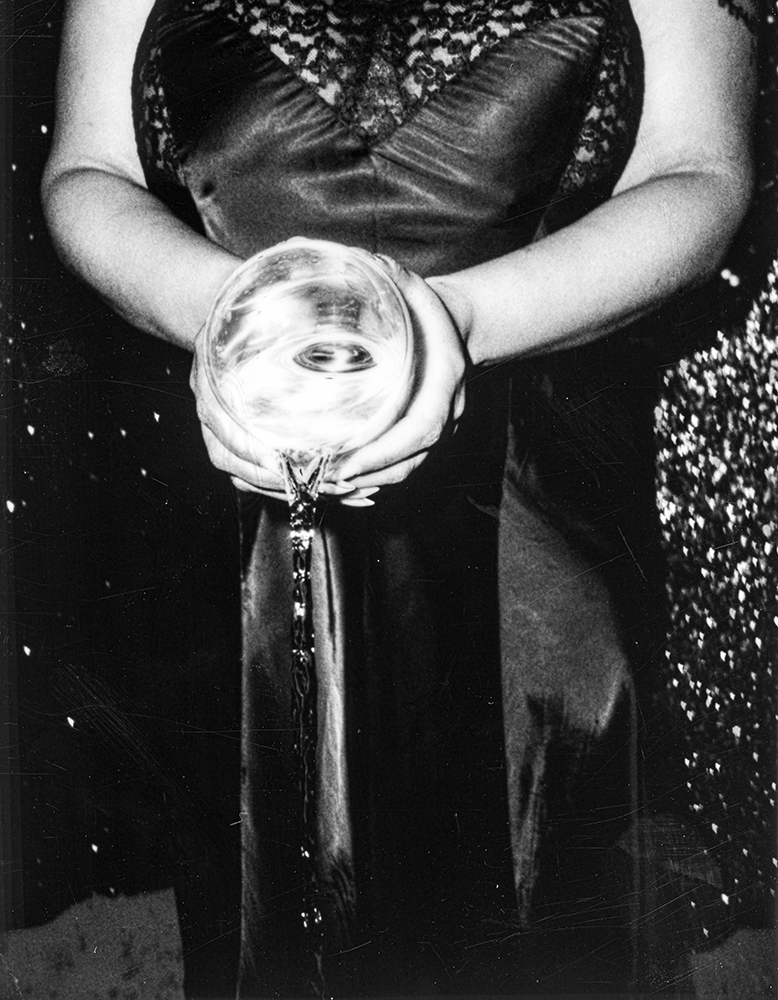

My practice is a personal meditation on the liminal space between our world and that of spirit. Less interested in the destination, my photographs work to document the shift. The moments between moments of time, the pause between the clap. Raised in a deeply religious household and honoring the language of afro spiritualism, my images reflect a lifetime of reverence for the divine while simultaneously bearing the cross of anti-Blackness that saturates our relationship to the land. In that, they work as a form of escapism in the hopes of a new world to come.

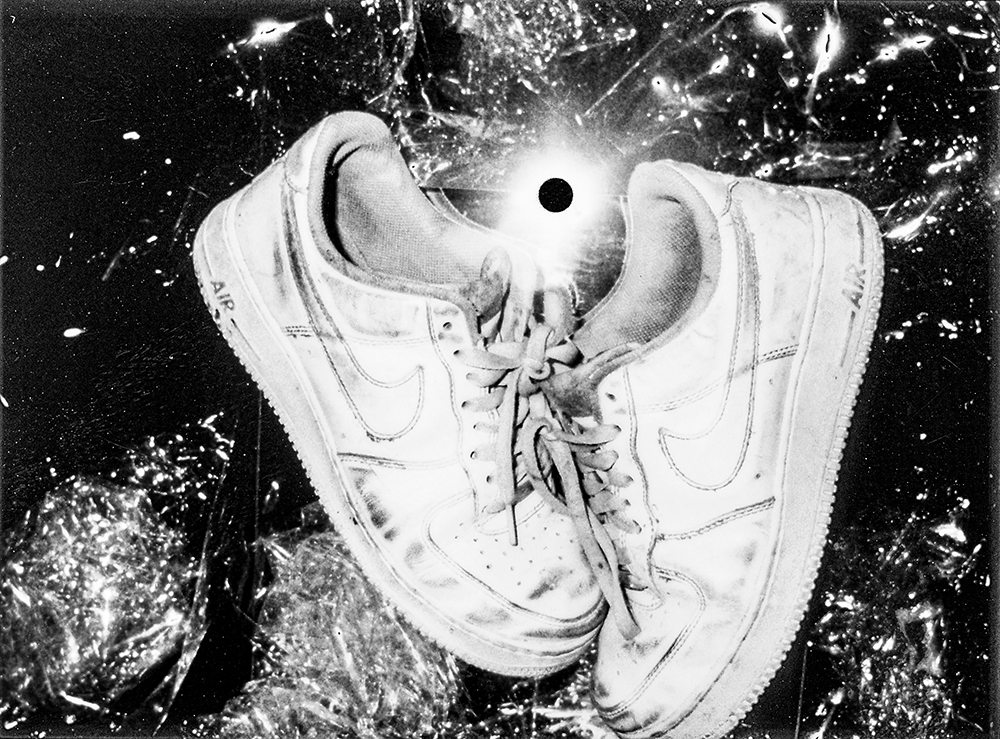

In my images, Black is potentiality. In the shine, there is god, and in fire, there is change. The concurrent states of Black existence (the past, the present, and our futures) can collapse in a singular moment, and image-making has the power to bear witness. The camera can act as a space for the refusal of a history of violence in that it may be used as a tool for communion. Now I find spirit in the collective hopes we place on a pair of sneakers, the way flowers reach for

the sun, and the eyes of those I love. All can act as a portal to other worlds and an entrance for spirit unto ours.

Drew Leventhal: Hey Nykelle, thank you so much for doing this with me. I wanted to start by asking how the last year since the Lenscratch Student Prize has been going? What are you working on and excited about?

Nykelle Devivo: Thank you Drew for taking the time to talk with me. How has the last year been? I want to answer as honestly as I possibly can. The last year has been really good for me actually! Some of the best growth in my career. Since Lenscratch I’ve had a couple of museum acquisitions and some big commercial gigs. I completed my second year preview in grad school and it was one of the largest shows I’ve ever done and was very well received. I was just winning.

DL: That’s so great to hear!

ND: Thank you! At the same time though everything is changing so fast. Right now I’m in a place where I’m reevaluating where I really want to go and I’m trying to disengage from the kind of direction I’ve been taking within my practice and also just my community in general. So I’ve just been sitting in a place of asking, “What are my desires within the photo world and what aligns with my morals and beliefs?” Because the kind of work I’m making is so specifically about Black spirituality and being and death. It seems unrealistic or untruthful to continue on this path of “Oh yeah, I’m really trying to get this show or this book or this gig.” I’m years into a fine art career, degrees and all, and it would be silly of me to pretend that I’m not within the institution. I’m definitely trying to reevaluate what that means for me and my practice.

DL: I can sense the disconnect there. There can be a tension between being inside institutions and making radical and meaningful work. So I want to pick that back up in a second, but I want to first return to all the amazing things that have happened to you in the past year. Why do you think that your work has been so well received in the year since Lenscratch? I found your pictures really amazing when I first saw them and I think that many people had a similar reaction. So I’m wondering if you can maybe tease out what some of those reactions have been and why they’ve been so positive and what you think that you’re touching on that’s really relevant right now?

ND: I appreciate you saying that. The work has gotten lots of great feedback over the past few years. I think much of it was riding the coattails of 2020 and George Floyd, when institutions started saying that Black people were valuable for the first time. So I feel like I was just in the right place at the right time. It didn’t necessarily have to do with the subject of my work. It’s just because I’m Black and I’m queer and I’m very loud and proud about those things which it seems like they’re now deemed valuable. Which is a really hard place to be. I feel like the work is only understood and made for spiritually compelled Black folk, which is a hyper specific group. And there’s very few opportunities to get into those spaces because there’s just not a lot of money there.

DL: And there’s not a lot of those spaces to begin with…

ND: Right there’s not a lot of them to begin with. So I haven’t gotten into those spaces as much as I would desire until recently. The work really took off in more white institutions however. I’ve had a white gallerist say to me, “Oh, this (white) woman just really loves your work.” I’m happy that it touches the donor’s heart, but this is very much not for her. Is this the sparkle effect? There’s a poppiness to my work that I think will always make it popular. People love shiny sparkly things. But I think there’s a disconnect between the meaning that the spark actually signifies and what people see on the surface of the image.

DL: That’s a great segue because I do want to get into the work a bit. As you just said it will always be seen as beautiful. But I went back through some of your previous projects and I think there’s some thematic through-lines. I want to start with the idea of the portal. Can you explain the concept of the portal and how it relates to your work? I’m coming from a background in anthropology, so my understanding of portals and mirrors and windows and reflecting on the “Other” is very specific.

ND: I think of portals as an entry point to speak to my ancestors. I think of portals as passageways to ancestral lands. I think of portals as the in-between space, between here and wherever the higher powers that be exist. I remember first intentionally saying that my work is related to the portal when I was creating Flashes of the Spirit. I wanted to don this sequin fabric as a means to create a direct connection or a direct conversation with an ancestor, with ancestral knowledge. I started realizing that the kind of ripples I was creating in light or the kind of ripples in the environment that come from moving through them with my body, all of that was a form of ancestor work in the same way of lighting a candle at my altar.

DL: I love that. As soon as you mentioned ancestral work I thought of the artist Dionne Lee and her video work Challenger Deep, which is showing right now at the Whitney Biennial. It’s partly about how survivalism can be a connection back to one’s enslaved descendants escaping North.

I know you said that you came from a very religious household. Was the concept of ancestors part of that upbringing or was that something that you added into your practice later on?

ND: That’s something I brought in later on. This is something I don’t always share but I was actually adopted at birth by white folks that lived in rural Nebraska. My mother who adopted me ran one of the largest Hindu ashrams in the United States. It was a spiritual retreat center in rural Nebraska. She had it from the 1980s to the 2000s or so. In peak season we’d have a thousand people and we’d have people from all around the world traveling to our 9 acres to practice in the temples throughout the farm. I grew up working in the altars, working in the temple, knowing the rituals. My mother didn’t want to force religion onto me because she was raised Catholic. She wanted me to find religion at my own pace. And I’m so grateful for that.

Because of her I started to understand ancestors as a kind of continuation of life, more of a Hindu perspective. But once I moved away to the west coast when I was 18, I reconnected with my birth family. I realized that I needed to have a Black form of spirituality, something that was grounded in the identity from which I was so disconnected for the first 18 years of my life. Afrofuturism became a means to understand my religion and spirituality.

DL: That’s an amazing story. Thank you for sharing. What kind of writers or thinkers in Afrofuturism, photographers too, were you most inspired?

ND: Sun Ra has to be first and foremost. At the San Francisco Art Institute I studied under the painter Dewey Crumpler. He would tell me stories about hearing Sun Ra. He heard it and it just changed his worldview instantly. And so he put me onto that music and he put me onto the kind of language that informed it. I remember being like, this is it. Dewey called Sun Ra a freak. In jazz terminology it means he was tapped into something sacred. And I was just like, that is what I want to be informing me. Also in undergrad I got really hyper-obsessed with the Japanese photographers of Provoke magazine.

DL: I absolutely love that stuff as well!

ND: It’s truly amazing.

DL: I really can see the influence in your work as well.

ND: I was trying to make the arguments through my undergrad thesis that their work was the closest we have to understanding a Black vernacular within photography. All these Japanese photographers are informed by jazz, through a few degrees of separation. They’re informed by the Abstract Expressionists, who’re informed by Black artists. They’re creating new levels of freedom and they’re connecting to something more ancestral within themselves. It’s emotional at its core, an emotional response with the camera. This is what we need more of in Black image-making.

DL: Makes me also think of Ming Smith’s work, her renaissance through Aperture and her inclusion at a recent show at the Guggenheim.

ND: Exactly. She’s collapsing time. There’s a before and there’s an after and there’s a present. And to me, being a freak (again in the jazz context) is being able to collapse all of those into the moment. Photography to me is so hyper specified on the past or on this specific moment. It’s a freezing of time. But the Japanese were saying, “well, there’s a past and there’s this future that we’re moving towards. And somewhere in between the image, the shutter happens to go off.”

DL: And the future is in that present. Right? You can’t ignore it. I like what you are saying about translation. It’s a fascinating idea in Japan, these photographers getting partially inspired second and third hand; from Black American artists to white Americans on the bases to the Japanese. In a way, with what you’re doing, it’s coming all the way back around. And I love that kind of cycle.

It’s almost a refusal to directly image, to depict. Do you see your work in a way, by not directly photographing bodies or altering the images, as a refusal to image Black bodies?

ND: Certain types of Black bodies are just shown over and over again. And that is seen as success. “Look, we did it. We solved racism.” Okay, but it’s still depictions frozen in time, the same photographic violence repeated. So can we hack the medium to do something different? I had a great Indigenous professor at SFAI who told me to start with the technology itself and kind of blow it up from there. We have to go to the foundation, we have to blow up the master’s house. You can’t just use the tools. So I needed to question the medium a little bit more. Either I’m cloaking myself or, as in my image Mama Wata, it just becomes a Black figure which is a representation of the void (or portal). Black skin doesn’t necessarily need to be present to be speaking about something inherently, spiritually, intrinsically Black.

DL: I think that’s really beautiful. Coming back to the ancestor question: do you feel that you are in negotiation with ancestors or is it more of a conjuring? Are they also making the pictures with you?

ND: This is a question my advisor, Paul Sepuya, asks me every time he walks into my studio, and I never have an answer for him. But that’s because I think both things are happening at the same time.

DL: I think that’s a valid answer.

ND: I think that when the flash goes off, the light that is cast from the device, the act of exposure and the act of light being thrown or shed, that is a spirit shooting out. As the light hits the reflected material, be it sequin, be it water, be it skin, wherever it appears in my works, that is also spirit manifesting and speaking through me. Underneath that fabric is an ancestor telling me to be, in this exact moment, me. We create it together.

DL: Have you ever had that feeling when you’re making a picture and you know instantly that it’s a good image? It was not preordained, but it was a gift. I love that feeling of knowing the gift happened. And sometimes you don’t know it immediately and the gift shows up later or with editing. So maybe ancestors and photography, they play with us a little bit. Sometimes they don’t make it easy.

ND: I think that’s one of the main reasons I’ve moved away from digital image making. For the most part I work with Polaroids. Now there is some film and a bit of digital sprinkled in. You start to see those defects happening and I especially love Polaroids because there’s a tangibility to the material itself. There’s something sacred about that process that can only happen with a medium that allows for chance to happen. And so I try to allow for those accidents to happen. I try to give space for that. Sometimes I’ll throw my Polaroids on the ground, even though I know it’s a good photograph. I just throw it on the ground and step on it and allow for it to be destroyed if it’s meant to be destroyed. And if it’s meant to become better, it’ll become better.

DL: Trusting the artistic, whatever you want to call it, artistic process or ancestors or God. I just have one last question. I was wondering if you could talk more about what’s next? You have one more year of grad school, you have a thesis show coming up, which is really exciting. Where do you see your practice going and evolving and what are you interested in next?

ND: I see my current project, The Crossroads, evolving. It is going to be released as a book in the near future. That’ll be a great culmination of the past 10 years, but it’ll also be kind of a chapter end where I can say, ”Okay, I did this type of work. Now I am moving towards something new.”

That something new is partly honoring the kind of rage that I feel the Black community is feeling right now. The righteous anger, the knowledge that our system is failing and falling apart around us, that we’re about to see the end. There’s something exciting and beautiful about that and there’s something destructive and terrifying about that. I want my future work to embody and hold that anger. At the same time I’m concerned with a level of care that I want to somehow embody, because I see my photographic practice as a loving gesture towards my ancestry. Even if there’s a violence in the photo, it’s still very much an act of holding. So how can I hold those tensions in the future? I need people to know that this work is for us and I’m angry. I need people to feel the embodiment of that rage somehow. And I don’t know if I’m going to be able to accomplish that, but that to me is my sole task moving towards the graduate thesis show.

DL: It feels like a paradigm shift in a way, you are approaching this desire to express things that you felt were slightly more hidden.

ND: Yes it is a paradigm shift. Look around this is not the only genocide happening right now. What’s happening in Palestinian? There’s a lot of anti-Blackness that makes us erase all the other things that are happening in the world to my people. But it feels like we have entered into a system where we are creating work for the upper echelon of the white art world, for investors. And I’m over it.

DL: I’m definitely over it.

ND: Yeah, we’re over it. Okay, now what does that mean? I don’t know quite yet. And I’m really excited to be a part of the community as we figure that out.

DL: That’s really beautiful. Thank you. I think that’s a great place to end, with many possibilities for the future.

Drew Leventhal (b. 1995) is an artist and anthropologist concerned with notions of community, historiography, and ritual. Working in an ethnographic style, his images engage with contrasting ideals of imagination, lineage, life, and death. Drew holds a BA in anthropology from Vassar College and an MFA in photography from the Rhode Island School of Design. His work has been featured in numerous publications and has been exhibited across the United States. Drew’s project Mason & Dixon was awarded the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize and he has been a finalist for the Aperture Portfolio Prize, the PHMuseum Grant, and the Film Photo Award. Drew is currently based in Philadelphia, PA.

Follow Drew Leventhal on Instagram

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025