Sam Comen

This week I will be featuring winners of Center’s recent competitions.

Los Angeles photographer, Sam Comen was awarded 1st Prize in the Project Launch Award, jurored by Darren Ching, Co-Director, Klompching Gallery, Brooklyn, NY and Creative Director, Photo District News and Debra Klomp Ching, Co-Director, Klompching Gallery. The winning series was Lost Hills, a project that took him away from the commercial and editorial world of his day job and allowed him to find the humanity in the people who help put food on our tables. Sam is part of an exhibit, Pro’jekt LA3: Dear Diary in Los Angeles at Space 15 Twenty, opening on April 13th.

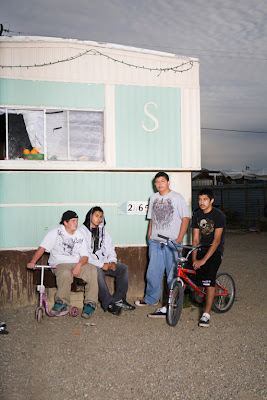

I traveled to Lost Hills, a town in California’s Central Valley, to make a series in a region with a storied and oft-photographed history. The Valley, the vast flat spine coursing through California’s interior, may be better known for what it represents than for the fact that it produces about half of all U.S.-grown fruits, nuts, and vegetables. It was the setting of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and the backdrop for memorable photographs made through the support of the W.P.A. during the Great Depression. In the last 70 years, many towns in the Valley have come to exemplify the contemporary small American working town.

Lost Hills has all the romanticized hallmarks of rural American life: it”s a tight-knit, one stoplight town where the 2,000 residents work hard to grow crops and drill for oil that feed and fuel the country. But Lost Hills is at the precipice of an upheaval: the farms that employ over half of the townspeople are completely dependent on water unsustainably imported from the northern part of the state, via the vast California Aqueduct. And the employees who embody the virtues of the hard-working American citizen are mostly undocumented immigrants, working for below-market wages, kept in check by threats of deportation and a backlog of willing immigrant workers.

Lost Hills at once looks exactly like the ideal American town of the past, and the wholly different American town of the future. The residents and workers operate in between both realities — living in a paradox. I believe that paradox, not an agrarian ideal of the past, nor a grim mega-mart parable of the future, is the only reality of life in the American town. I’m fascinated how the people I’ve photographed negotiate the contradictions, how they cope. Take for one example the young oil worker who is pictured in the traditional Mexican rodeo, or Charreada, dress. He envisions himself as his family’s head, and a noble rebel leader like Pancho Villa. But his younger brother and friends tease him from their cars, call him Señor Cervantes, and chide him for stepping outside of his humble surroundings — they think he’s delusional. My hope is that the tension in the photograph of this young man, and the tension I see in the other portraits in the series, gives American viewers insight into the paradoxes we all negotiate in our lives.

The way I’ve chosen to photograph in Lost Hills highlights that tension too. I’ve applied the toolset of contemporary commercial photography — saturated colors, deep depth-of-field, bright lighting — to the small town. This locale in American culture has traditionally been portrayed using a black-and-white reportage approach. I believe the contrast between established photographic tropes and this contemporary style mirrors the contradictions I see in Lost Hills. Further, the crisp, lit, medical, and somewhat removed stance of the portraits discourages an empathetic gaze, and instead invites the viewer to consider each photograph as an emblematic tableau.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shinichiro Nagasawa: The Bonin IslandersApril 2nd, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Lorraine Turci: The Resilience of the CrowMarch 16th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Rayito Flores Pelcastre: Chirping of CricketsMarch 14th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Louise Amelie: What Does Migration Mean for those who Stay BehindMarch 12th, 2024

-

Brandon Tauszik: Fifteen VaultsMarch 3rd, 2024