Success Stories: Beth Yarnelle Edwards

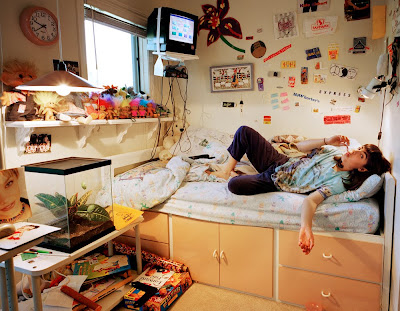

When I first started looking at contemporary fine art photography in a significant way, I profoundly connected with Beth Yarnelle Edwards’ images of girls in their bedrooms. I have kept an eye on her image making over the years and when I recently discovered she was about to publish her first monograph, Suburban Dreams, by Keher Verlag of Germany, I thought it would be a good time to not only recognize Beth as a Success Story, but learn more about what goes into her process of making work.

Beth was born in a small coal-mining town in Pennsylvania and relocated to Los Angeles as a child. She received degree in psychology from UCLA and then moved to the San Francisco Bay Area where she got a MA in Teaching English as a Second Language. After teaching for seven years, she took time off to be at home with her son. It was during that period that she realized her fascination with how people live and inspired by a writing course, learned to tell her stories in a visual way. She went on to receive an MFA in photography, but is now an adjunct professor of English as a Second Language at the University of San Francisco. “My day job is related in some ways to my interests as an artist. My purpose is to teach students to communicate in English and to navigate American culture. At the same time that I educate them, they teach me many important things about themselves and their ways of seeing the world.”

Beth has become an international phenomenon exhibiting in India, Belgium, and Iceland in the coming months. She has had solo museum exhibitions in France and Belgium, her work has been included in a number of books, she was the winner of the 1999 Center Project Competition, and her work is held in many museum collections.

Beth’s new monograph, Suburban Dreams

Congratulations on Suburban Dreams! Can you tell us how the book came about?

Thank you! I’m happy and excited about Suburban Dreams, which includes fifty-six domestic scenes from Silicon Valley and five European countries. I’d been working on the series since 1997 when I met Alexa Becker from Kehrer Verlag at Fotofest 2010, and I and was absolutely thrilled when Kehrer invited me to do a book. Suburban Dreams was released in Europe last January. It will be available in the US this September (2011).

This is my first monograph, so I had no idea what to expect and was somewhat nervous about the whole process. However, the people at Kehrer were so professional, so responsive, so intelligent, so talented, etc. that working on the book was a joy. I’m very proud of what we created together and consider myself blessed to have worked with them.

I first discovered your work when you were shooting children in their bedrooms. Obviously getting in behind closed doors is a passion of yours, and your ability to capture a scene in a formal way, yet have the moment feel unscripted, is an incredible talent. Can you talk about the way you work?

Before Suburban Dreams, I had created a 35mm black and white project with similar interests but which was completely fictional. Two of these images were published in The New Yorker and Harper’s Magazine. However, when I began graduate school, I felt the need to try something new and decided to experiment with medium-format, color, and a more documentary approach. I began with people I knew, and many were children who loved the attention and were also very natural in front of the camera. I would give every family a signed print of their photograph, and soon happy subjects were sending me on to their friends, neighbors, and relatives—all people who were strangers to me. When I started receiving invitations to photograph in Europe, I was introduced in various ways to even more strangers. The result is that most of my subjects have been people I had never met before.

I have a procedure for my first meeting with subjects as well as a set of rules for keeping things as truthful and natural as possible during the shoot. My first concern is always that people understand what they’re getting into, that they know what my pictures look like and where they might be seen. Originally, I would arrive at a first appointment with a box of prints, but now I can just tell people to look at my website. Either way, we talk about my photographs, my intentions, and my working methods. I answer any and all questions and require subjects to sign a model release. During this first visit, I observe carefully,

ask many open-ended questions, and if I’m ready, discuss possible scenarios. Concepts for the photographs are inspired by my observations, answers to my questions, and sometimes by direct suggestions from my subjects themselves. It’s my job to ensure that the ideas are original and authentic to the people involved.

Before the day of the shoot, we agree about the scenes we will do. I ask each subject to have two or three outfits ready that they like and frequently wear and that are appropriate for our concept. If any objects or supplies are needed (for example, food for cooking a meal), we discuss those too. When I arrive, I tell people to stay relaxed while I set up my equipment and my lights, if I’m using them.

I set up the frame of the photograph and then ask my subjects to improvise inside this space, to do what they would normally do in this given situation. I don’t usually pose people but rather wait for an authentic expression, gesture, or posture to appear. When I see it, I very quietly ask my model/s to hold that position for a second or two. I may ask someone to move a little closer or to turn a bit, but always I’m waiting for the authentic to appear. Since it takes people quite a while to feel truly comfortable and to be completely themselves, I just keep shooting and saying encouraging things. The first images are not usually the best ones.

Do you ever feel ill at ease with strangers, especially when you are treading on such personal space?

I love meeting new people, and these strangers have already expressed an interest in being in my pictures. Their wanting me to be there helps overcome any potential shyness. Sometimes I’m uncomfortable when I encounter compositional or technical difficulties and feel I’m taking too long to set up. People are gracious about it, but they tend to hover around, and that can make me nervous.

How do you find your subjects, and I’m curious to their reactions, especially about appearing in your book. Has anyone said they weren’t comfortable participating?

As I mentioned, I began with people I knew and then was introduced to others who in turn presented me to their contacts. Sometimes people would hear about my project and volunteer. In Europe my subjects have come to me in a variety of ways. My first experience was in France when I had a solo exhibition at Château d’Eau, the photography museum in Toulouse. At my vernissage, the director, Jean-Marc Lacabe, invited me to return to photograph local households. When I accepted, he placed a sign-up sheet on the wall of my exhibition so that anyone who came by who wanted to be photographed could sign up. In Spain I worked for an architecture magazine that provided a list of households at all social levels, including two men who were squatting in a WWII bunker. When I was artist-in- residence for the Mannheim Photography Festival, the festival office advertised for volunteers. Regardless of how I’ve met my initial contacts, in every location I’ve photographed, the people I’ve met have wanted to introduce me to others. By the end of a project, I usually have a list of many more people than I have time to meet.

One of my requirements for models is that they first view my work and be comfortable with where their photograph might be seen, so this hasn’t been an issue. I believe I’ve visited more than two hundred households, and I can only think of one that turned me down. However, I have met a few people I didn’t feel I could work with. These were rare, perhaps five or six out of two hundred plus visits, and they were always men. The problem in these situations was that the person wanted to tell me exactly how and what to photograph. I’m respectful, so if some aspect of a subject’s daily life is out of bounds, I will come up with another concept I believe is also true to the people involved. I’m very clear when I present my ideas and usually explain what I observed or heard that inspired me. Sometimes my subjects will originate a great idea, and we will use it. What I refuse to do is create something that looks like a magazine ad or that tells a story that seems false.

You’ve been creating these portraits in other cultures and countries. Have you found any differences?

Before working in Europe, I’d attributed my success to being a cultural insider. I thought people were comfortable with me because I seemed familiar, so I was really nervous when I began in France. I could speak French but not very well, and I had heard that French people wouldn’t be willing to let me poke around their homes and ask a lot of questions. I was surprised and delighted to find the opposite, but of course these were people who had already seen my work and volunteered to take part. My French models were not only very welcoming

but also less self-conscious than many of the Americans I’d photographed. While I would sometimes get requests from Americans to photograph them on their “good side” or make them look thinner, my French subjects were much more interested in what I would discover in their lives and their homes. It was fun for them, and I was almost always treated like a special guest and asked to remain for lunch or dinner. This friendliness and openness have continued in all of the European countries where I’ve worked.

What do you personally take away from this experience, this privilege of having access to other people’s lives?

I’m deeply grateful to the people who have opened their homes and shared their lives with me. They’ve added to my understanding of the human condition, and I feel the experience of working together has made all of us richer. People have told me that my interview has caused them to see or think about their lives in a new way. I’ve also made many wonderful new friends.

What’s next?

For the time being, I will continue to work in the same manner but in new places. I made a lot of new photographs this summer in Berlin and am in the process of editing them. I’d very much like to photograph in Asia.

I have a couple of new ideas—one about death as well as a project on love goneawry—but those will have to wait until I have the time and resources to execute them.

What advice can you give emerging photographers, especially on presentation, on networking, on consistently producing excellent work?

I’m rather shy about approaching people in the art world, so many of my opportunities have come from structured situations like Fotofest or from sending things by mail. My presentation is pretty simple: a box of good prints for an in-person visit, good scans sent by email or on a CD, and my website. I make cards with my images on simplecard.com and use them as leave-behinds or for correspondence.

I believe that excellent work begins with passion, good skills, a willingness to work very hard, and a strong sense of one’s unique talents and interests. An excellent photographer should be making the work that only she or he can make; in other words, one should be demonstrating a unique vision. What is also necessary is ruthless editing and taking the time to really consider new photographs before releasing them into the world.

What opportunity took your career to the next level?

At my first Fotofest (1998), I met a Dutch artist, Jan van Leeuwen. We decided to trade tips by email, and one of his was about a French competition. I entered, won the gran prix, and was exhibited with the ten finalists. That exhibition led to more in France and eventually to my first project there. Taking my work to Europe was very important for my career.

Has social networking changed how you promote and market your work?

Not yet. I’m way behind in this area. I’m on Facebook but rarely check unless someone friends me or sends an e-mail directly. I joined because I thought it would be good for promotion and for meeting fellow artists, but I haven’t figured out yet how to make it work. I’ve posted a few things but am still pretty awkward about it.

Do you ever have periods of self-doubt and feel creatively unmotivated?

I don’t lack inspiration or motivation, but I often lack the time and resources I need to act on them.

And finally, what would be your perfect day?

My perfect day would last at least a month, and during that time, the sun would never set, and I wouldn’t need to sleep. I’d be able to do my work without any interruptions. When I felt satisfied that I’d accomplished something interesting, I’d spend the rest of the time with my loved ones.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Paccarik Orue: El MuquiDecember 9th, 2025

-

Lauri Gaffin: Moving Still: A Cinematic Life Frame-by-FrameDecember 4th, 2025

-

Dani Tranchesi: Ordinary MiraclesNovember 30th, 2025

-

Art of Documentary Photography: Elliot RossOctober 30th, 2025

-

The Art of Documentary Photography: Carol GuzyOctober 29th, 2025