The Bootsy Holler Interview

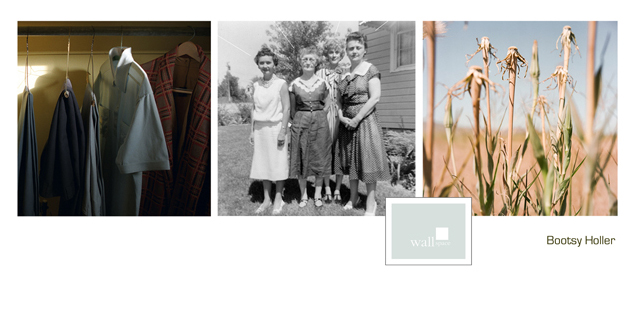

I have always loved this photograph by Bootsy Holler. It’s from her Declassified project and is a lovely vista with a sign of HOPE, set beneath a huge open sky. When I first saw it, I didn’t know that it reflected her personal history, it just spoke to me in its simplicity and message. In some ways, it reflects Bootsy herself–direct, positive, finding beauty in simple things.

I have always loved this photograph by Bootsy Holler. It’s from her Declassified project and is a lovely vista with a sign of HOPE, set beneath a huge open sky. When I first saw it, I didn’t know that it reflected her personal history, it just spoke to me in its simplicity and message. In some ways, it reflects Bootsy herself–direct, positive, finding beauty in simple things.

I have known Bootsy for a long time–she lives in Los Angeles, we are both members of the Six Shooter collective, and I consider her a close friend. I wanted to interview Boosty to celebrate her upcoming retrospective exhibition, Bootsy Holler: Nuclear Family, that opened at wall space Gallery in Santa Barbara on March 3rd and runs through April 26th. The show will feature four bodies of work–each with a different approach and focus, but all fall under the umbrella of her personal history. There will be an Artist Talk on March 14th from 3-4 with an Artist Reception to follow from 4-7pm. Bootsy is an intuitive commercial and fine art photographer who has been shooting professionally and exhibiting for more than 15 years. Her career as an artist started as a youthful obsession with fabrics and fashion, leading to a degree in textile design. She moved into styling, art direction, and a small design manufacturing company she founded, which incorporated photography, and in 1999 let go of them all to focus on photography as an art and trade. From that journey, she gained three things: a devotion to craft, a deep understanding of style, and respect for the power of beauty. When you look at Holler’s fine art, you usually find self-portrait work or the mundane daily life we often pass by. Focusing on the spirit of people, things, and moments, she has gained a reputation for being able to communicate the intangible.

Bootsy is an intuitive commercial and fine art photographer who has been shooting professionally and exhibiting for more than 15 years. Her career as an artist started as a youthful obsession with fabrics and fashion, leading to a degree in textile design. She moved into styling, art direction, and a small design manufacturing company she founded, which incorporated photography, and in 1999 let go of them all to focus on photography as an art and trade. From that journey, she gained three things: a devotion to craft, a deep understanding of style, and respect for the power of beauty. When you look at Holler’s fine art, you usually find self-portrait work or the mundane daily life we often pass by. Focusing on the spirit of people, things, and moments, she has gained a reputation for being able to communicate the intangible.

Congratulations on your upcoming exhibition! First can you share about how you came to photography and a little bit about your fine art career?

I was given a camera when I was probably 7 and spent most of my time documenting my animals and friends. I was always asking for better equipment, so the interest was there. But I thought I was going to be a clothing designer, so I never looked at photography as my art. My Grandmother was a great seamstress, and I definitely got her skills. I went to school for textiles, but I was still shooting all the time. I was asked to photograph my boyfriend’s band and also gave them fine art images for their album covers. So photography slowly took over as a career. I would say it was very organic, as is all my art.

After college, I was definitely making more art and experimenting. I’m pretty much a self-taught photographer. My first show was in 1995, and I did a large installation of photo/mixed media in a cafe. I’ve been showing ever since. In 2000 I started making a living with advertising and editorial photography while still producing personal work on the side, though I feel like I really started working on my fine art career 8 years ago when I moved from Seattle to Los Angeles. Which is also when I met you.

What are/were some of your influences?

In the past I was looking at a lot of Egon Schiele, Frida Kahlo paintings and Sally Mann, Diane Arbus, Cindy Sherman, Jock Sturges, Duane Michaels, Man Ray books and photography exhibitions, but also fashion photogs like Helmet Newton, Annie Leibovitz and Richard Avedon plus I love Joel-Peter Witkin’s and Peter Beard work.

I understand that the exhibition is a mini-retrospective, featuring four different bodies of work–how does it all tie together?

How does it all tie together?I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately.

On the surface, it’s about family and where I’m from. Also the simplicity and beauty of a place or thing, but as I have pushed myself to analyze the work I feel I’m looking for a deeper sense of self in the world through family history. The work has become a way for me to actualize my potential as an artist, daughter, wife, and mother.

What I think is so interesting about all of these projects is how comprehensively you have examined your life and surroundings for project ideas, creating work that is intimate and creating work that is ultimately a global investigation. And all your approaches to each project are unique. Let’s start with the Ruby & Willie work. How did that come about?

R&W began when I shot a few photos one night at my Grandpa’s house. It was such a space in stasis as my Grandmother had died 25 years earlier, and nothing had changed. I was so in love with the roll of film I had shot that Christmas holiday that I announced I was coming back to document the whole home. I went back three more times over five months, and the last trip corresponded with Willie’s funeral. He had fallen in February and never made it back home after that. The house was soon stripped of its decor and sold.

Over the years, after Ruby’s death, I had been collecting things from the house, including a box of family photos and vintage dresses that inspired the Visitor project.

I love the concept of the Visitor and also your presentation of the work. Has the process of placing yourself in various moments of your family history changed your emotional relationship to your family? Has anything cathartic resulted from the project?

I love the concept of the Visitor and also your presentation of the work. Has the process of placing yourself in various moments of your family history changed your emotional relationship to your family? Has anything cathartic resulted from the project?

The work from Visitor changed my emotional relationship with my mother, most definitely. It has given me a place to ask questions and learn about her past and my families. Understanding her as a child and as a young woman has made me feel empathy for her as a mother and her lost dreams in life. I have a broader view of how and why she became the person she is. I can’t say I feel immense relief through the work, but it does bring up strong emotions for me when I think about our relationship. Having to sit and think about the larger picture and what it means does become more cathartic.

Declassified is a fascinating project, told from the perspective of your very secretive father and the beautiful landscape of your childhood that is charged with a tainted history. Has learning about Hanford as an adult changed how you saw your father and the landscape of your growing up?

Similar to learning about my mother through my work, talking to my father about his knowledge on Hanford, plutonium, nuclear waste and the now many declassified documents from the Department of Energy, has been fascinating. I’ve always seen my father as an honest man and one who cuts through the crap, not what you think of when you visualize our Government. So hearing my father speak about Hanford doesn’t change my feelings about him but I do feel that working for the D.O.E. was soul crushing for him and that talking about it now is therapeutic. Very few people are left to talk about how Hanford came to exist, and he speaks for my both my grandfathers.

As for the land, I think it is beautiful and because of the Government it has an untouched feeling but it is also the most toxic place in America. My feeling is that man is destroying the Earth in many ways and not just with nuclear waste – look at the pesticides spread over the planet, litter and chemicals flowing into our oceans. It’s complicated how I feel about it all.

But wait, you’re asking how I feel about growing up there? As an artist, it was hard to grow up surrounded by biology and science but at the same time I was around highly intelligent people. Though I would never go back to live there, it is amazing to think I grew up in this oddly secretive Government town, and it was all normal feeling to me.

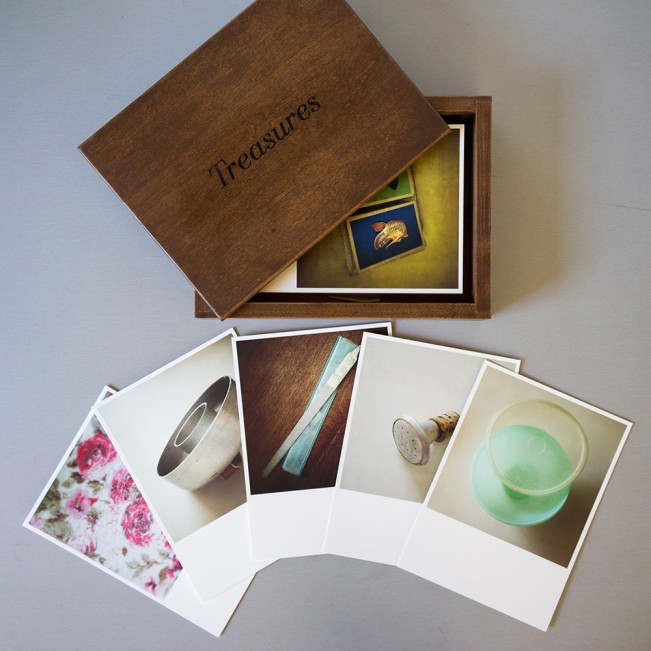

You have a very clever approach to your project Treasures. Can you share how you started that project and why you selected to present it this way?

It is often said you should photograph what you are surrounded by. And that is definitely why a lot of my work is family based. With a five-year-old I often can’t shoot like I used to. While visiting my mother, I was blown away thinking about the fact that this old scrubby in the drawer had been there my whole life. So in my own way I wanted to show the Scrubby and all its beauty to the world. I pulled out my iPhone, and the series began. I worked on these artifacts over multiple visits for brief periods of time as I was either dealing with my son or my mother.

Because I started the project when I was 44 and all these items were at least that old I decided to photograph as many as 44 things. The small size seemed appropriate for the work and what better place to live than in a Treasure Box.

What’s next? Do you think you will turn your camera towards your immediate family any time soon?

The next thing is to work on Visitor for my father’s side of the family and produce a small run of handmade art book for the collection. My immediate family comes and goes through my work with Mouse dog and Drake showing up in Visitor. My husband is harder to pin down but maybe he will show up for a few.

I’ve started working on more abstract work about color and feel. So I may venture out of the family for a project.

And finally describe your perfect day.

A perfect day can be either feeling like I have accomplished something for myself or my art or lying on a beach in a foreign land reading a good book (with a nanny, of course).

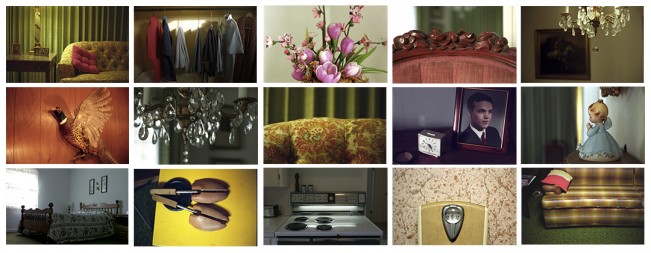

Ruby & Wilie: my grandparents’ house

These images are just a sampling from the 26 rolls of film I shot. The images were taken in Ruby and Willie’s home, located at 1824 Davison, Richland, Washington. Ruby, passed in 1978, leaving Willie to live alone. He lived in the basement and kitchen, not touching any of the rooms. I documented each room as I would a museum, capturing all the details in the kitchen, living room, dining room, hallway, boys’ room, girls’ room, Ruby’s room, the downstairs TV room, and finally Willie’s basement bedroom.

These images are just a sampling from the 26 rolls of film I shot. The images were taken in Ruby and Willie’s home, located at 1824 Davison, Richland, Washington. Ruby, passed in 1978, leaving Willie to live alone. He lived in the basement and kitchen, not touching any of the rooms. I documented each room as I would a museum, capturing all the details in the kitchen, living room, dining room, hallway, boys’ room, girls’ room, Ruby’s room, the downstairs TV room, and finally Willie’s basement bedroom.

I began documenting their simple décor one December when I came to visit. Maybe I knew this home, which looked to me like a movie set, would soon be destroyed. Within four months my grandfather fell sick and passed away. This home, which hadn’t been changed in more than 25 years, was soon stripped down to nothing. Everything was gone.

As generations leave us, they take with them their environments. I used photography for what it does best: to document a place and time before it is gone. Each photograph will be able to stand-alone or be combined in a linear or stacked grouping describing a single room or is also beautiful as a large grid of images forming one huge piece.

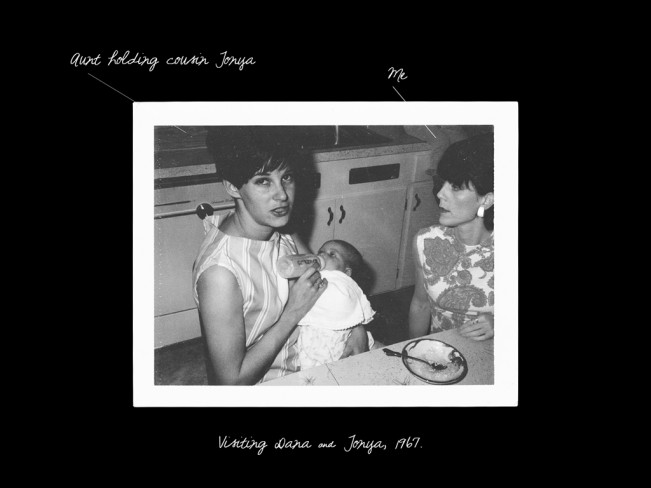

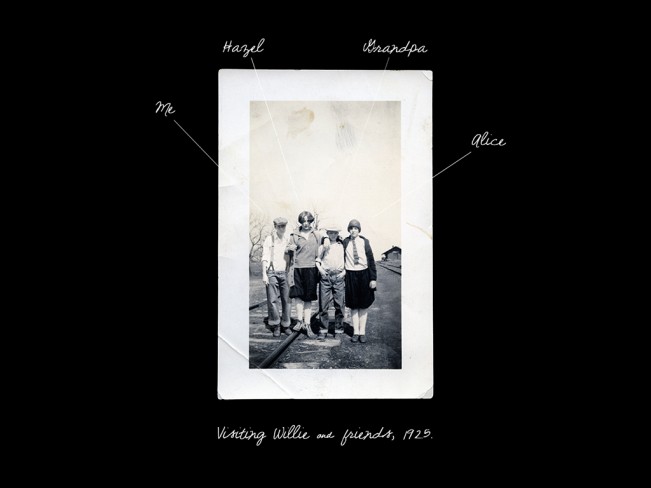

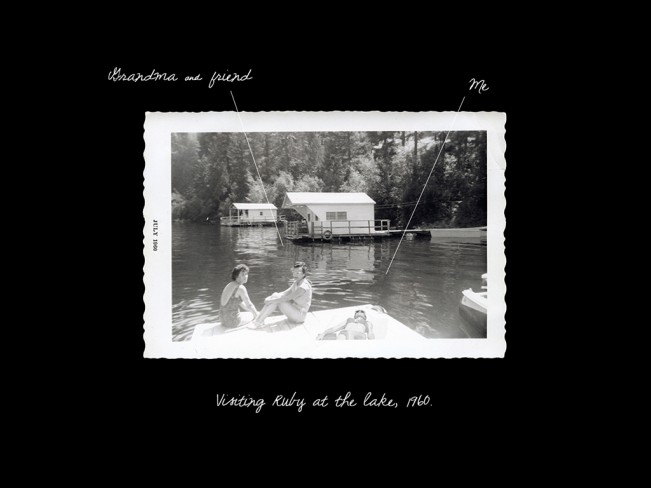

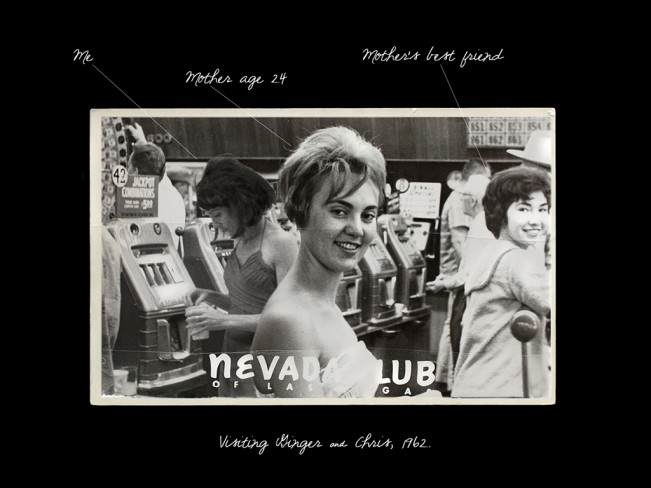

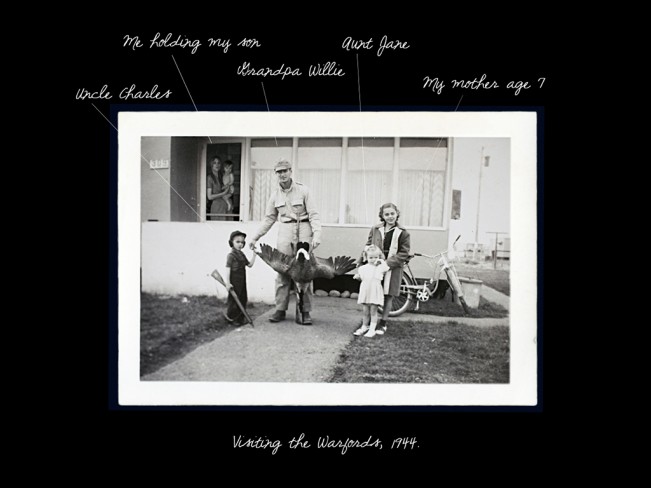

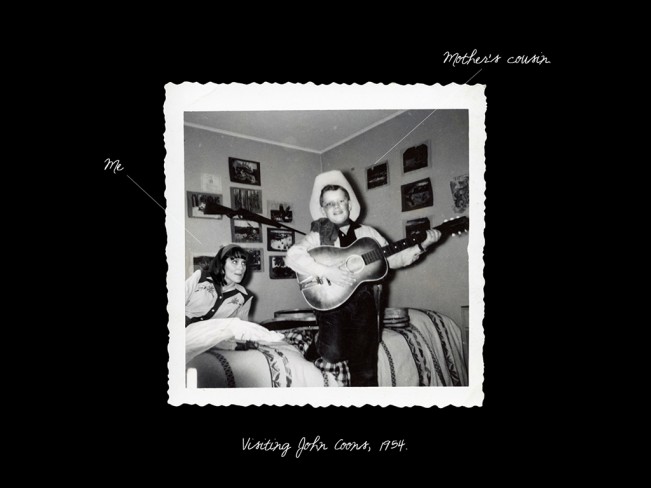

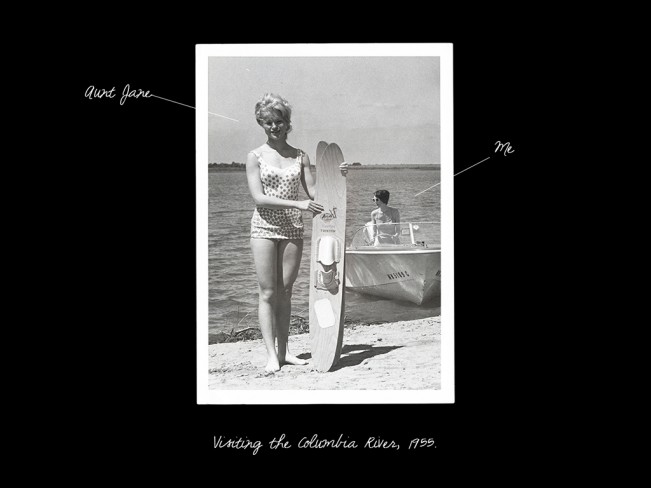

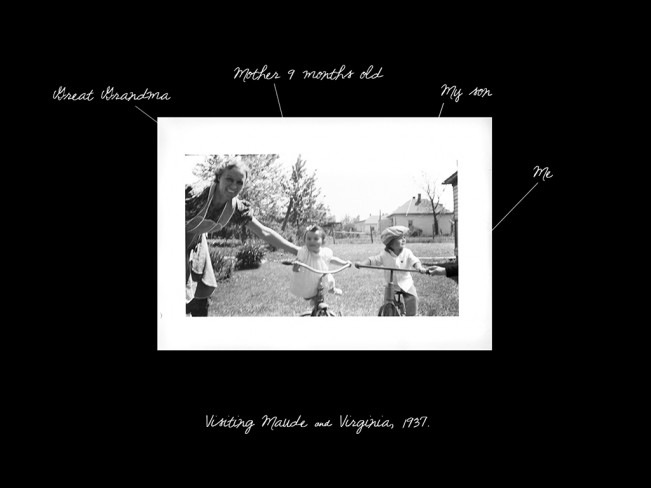

Visitor: rebuilding the family album

I’ve often wondered what it might be like to experience the frozen moments in my family photographs and be connected. I want to understand myself better and my DNA so I can experience where I have come from and how these people have influenced my being.

The goal with Visitor is to reinterpret my intimate family snapshots, explore time, history, meet and understand family while blurring boundaries. I’m trying to understand my ancestry and, in particular, my mother and why she is who she is. To understand how I have been put together and created over generations and time through family to become who I am. I created a look driven by the era of each original photograph, pulling a wardrobe I’ve collected over the years and inherited from my grandmother, who was a seamstress. By making a composite I’ve placed myself in each world I want to revisit. I want to understand my family stories and memories through my research of each image and the feeling of setting myself back in the moment as I wait for the timer to snap the shot.

In my efforts to be authentic to the original photograph, I have matched the format of the original image: some soft grain and blown out whites help match the old, authentic vintage feeling of each snapshot. Each image is printed in the original size and placed on a black photo album page similar to how the images were found with white ink and handwritten text to guide the viewer through the album.

Famed work is shown in a shadow box 14”x14” in edition of 10 with the image floating on black archival mat board and handwritten white ink. Attached to each frame is a magnifying glass so the viewer can take a closer look.

DECLASSIFIED: hanford a national secret

Images of a time, a place and a secret

In December 1942, one year after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt claimed over 600 square miles of desert steppe land near the confluence of the Columbia and Yakima rivers in Southeastern Washington State for a top-secret project. Up to that point the region had been a quiet farming community, but due to its unique ecological and geographic properties it was chosen to be the home of the world’s first nuclear bomb. These 600 square miles are now considered to be the most toxic place in America. This place is Hanford Washington – where I’m from.

In December 1942, one year after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt claimed over 600 square miles of desert steppe land near the confluence of the Columbia and Yakima rivers in Southeastern Washington State for a top-secret project. Up to that point the region had been a quiet farming community, but due to its unique ecological and geographic properties it was chosen to be the home of the world’s first nuclear bomb. These 600 square miles are now considered to be the most toxic place in America. This place is Hanford Washington – where I’m from.

The story of Hanford had been a national secret, one that few people fully understood until August 1945, when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Only in the wake of those 135,000 deaths did the people of Hanford begin to learn the purpose of their town: to produce the plutonium that fueled one of America’s atomic bombs.

As a native of this profoundly secretive and conflicted place, I grew up in a culture where larger truths were never known. My father managed Nuclear Operations at Hanford and has only recently begun to reveal his secrets.

As a native of this profoundly secretive and conflicted place, I grew up in a culture where larger truths were never known. My father managed Nuclear Operations at Hanford and has only recently begun to reveal his secrets.

As an artist, I am drawn Hanford’s many ironies, not the least of which are: the extreme beauty of the untouched land that covers a vast amount of toxic waste, a high-school mascot that symbolizes my hometown’s infamy (a nuclear mushroom cloud), and street names which record the legacy that led to the death of so many and which changed the course of history.

I wanted to document Hanford as a testament to a resilience in the face of man’s destructive capacity.

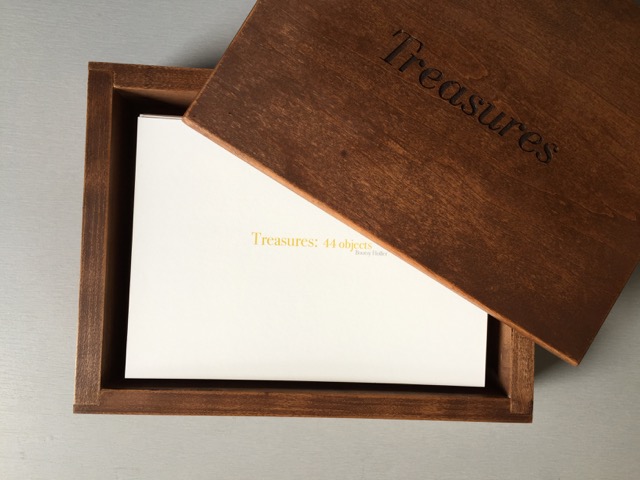

Treasures

“As photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure.”

The photographs in Treasures are of simple objects from my mother’s home that I have known all of my life. My mother has always been very particular about how she likes things; every item has its place, every task has its way of being done and so these things and this way became part of my life too.

The photographs in Treasures are of simple objects from my mother’s home that I have known all of my life. My mother has always been very particular about how she likes things; every item has its place, every task has its way of being done and so these things and this way became part of my life too.

Susan Sontag is speaking about insecurity and how taking photographs gives us little trophies that capture a time and a place, which gives us a sense of comfort.

The truth is; I am uncomfortable talking about my work. I am uncomfortable revealing parts of myself that I’d prefer to keep hidden. Maybe I’m afraid of what you will think, or maybe I’m afraid of what I will learn about myself. Either way, over the years I have allowed or even forced my work to speak for me — to tell truths that I cannot.

Initially, I thought Treasures: 44 objects was about my mother and how she treasured her things more than she treasured me. But I realize now that this work is less about me being unnoticed by her, and more about my fear of becoming her and affecting my son through the lessons I learned from her.

Limited to editions of 5, all 44 images are printed on 5×7 inch cards and come cradled lovingly in a wood box for display.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Jonathan Silbert: InsightsFebruary 19th, 2026

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026