Ken Weingart interviews Mark Seliger

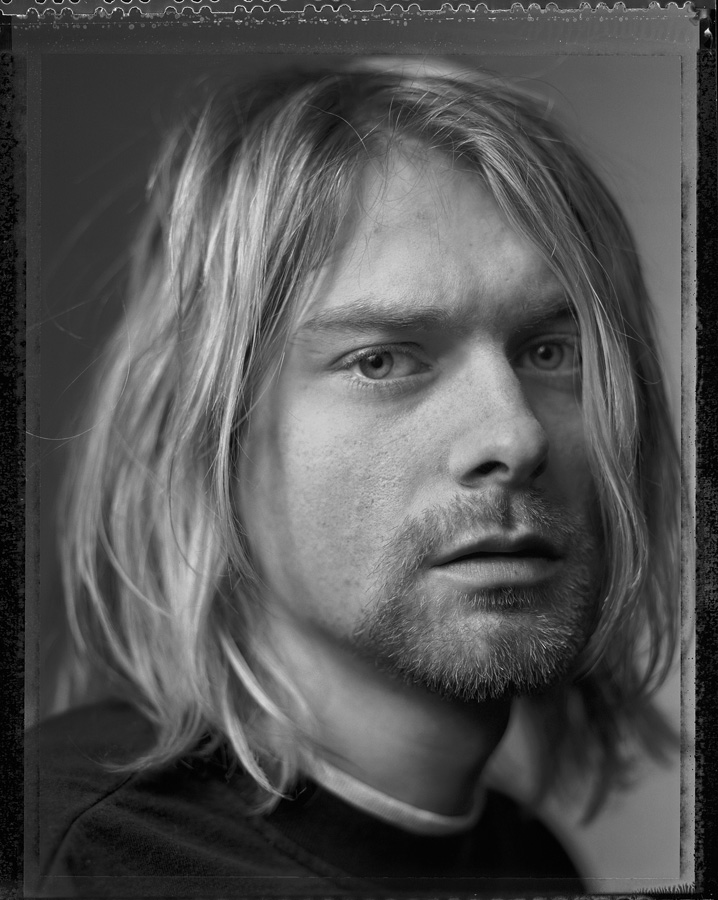

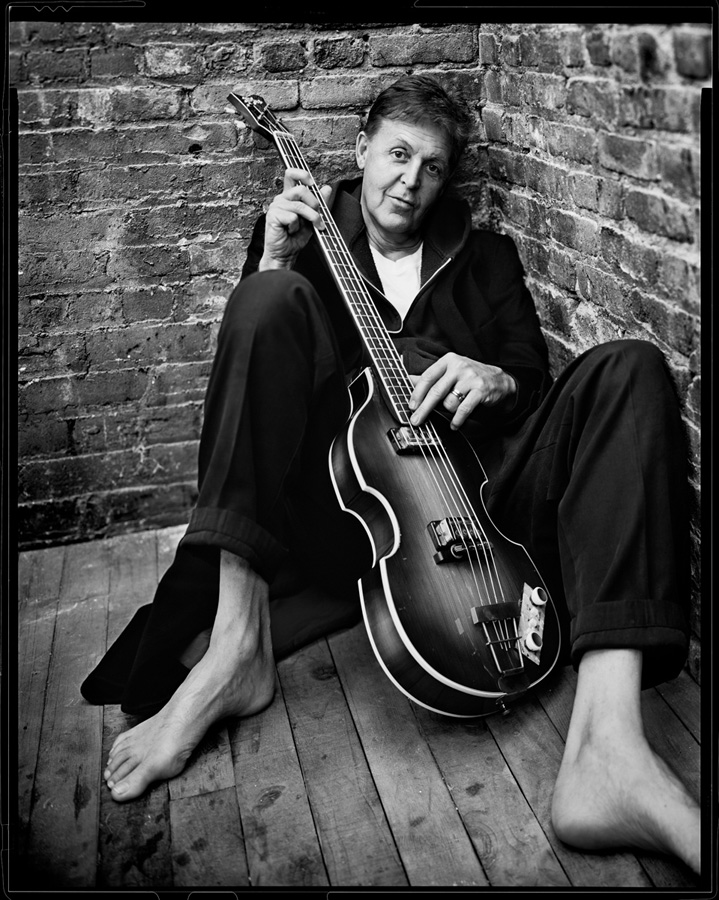

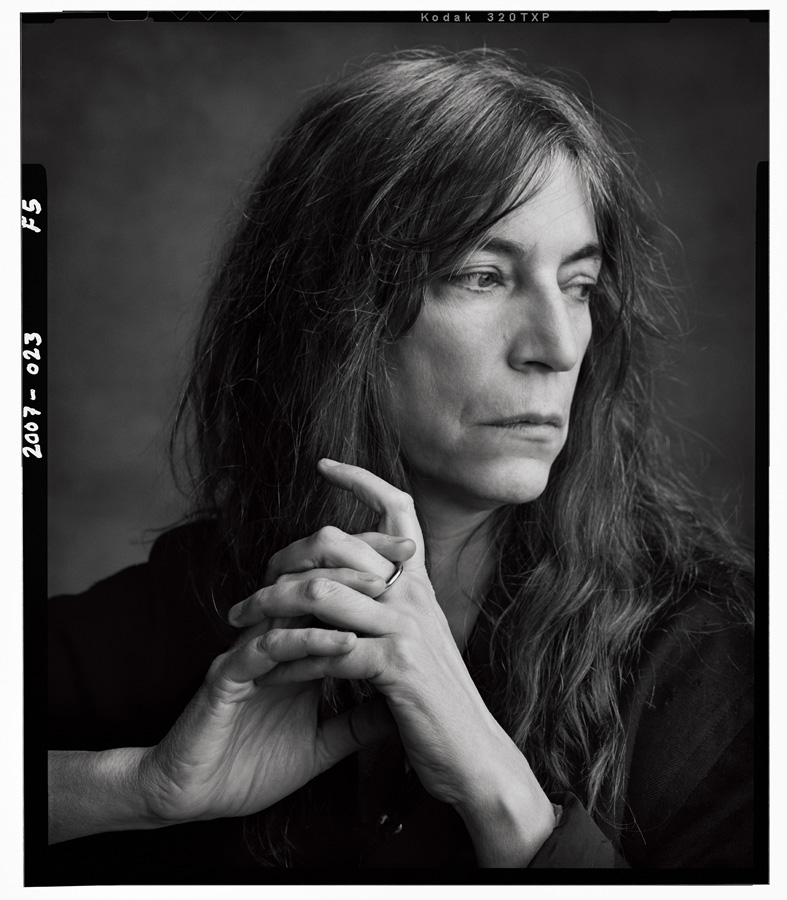

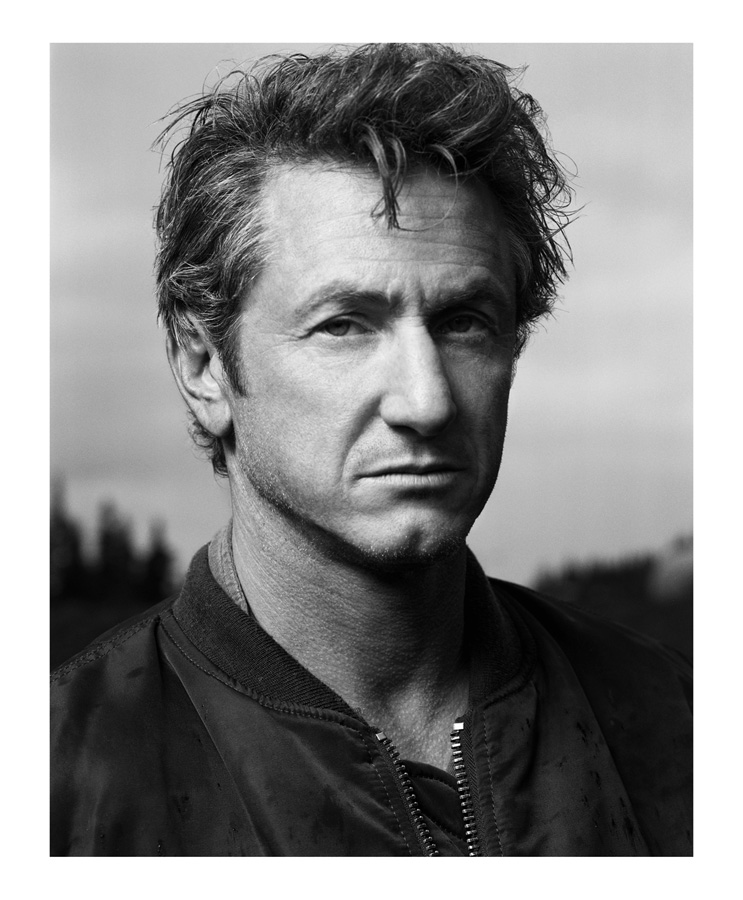

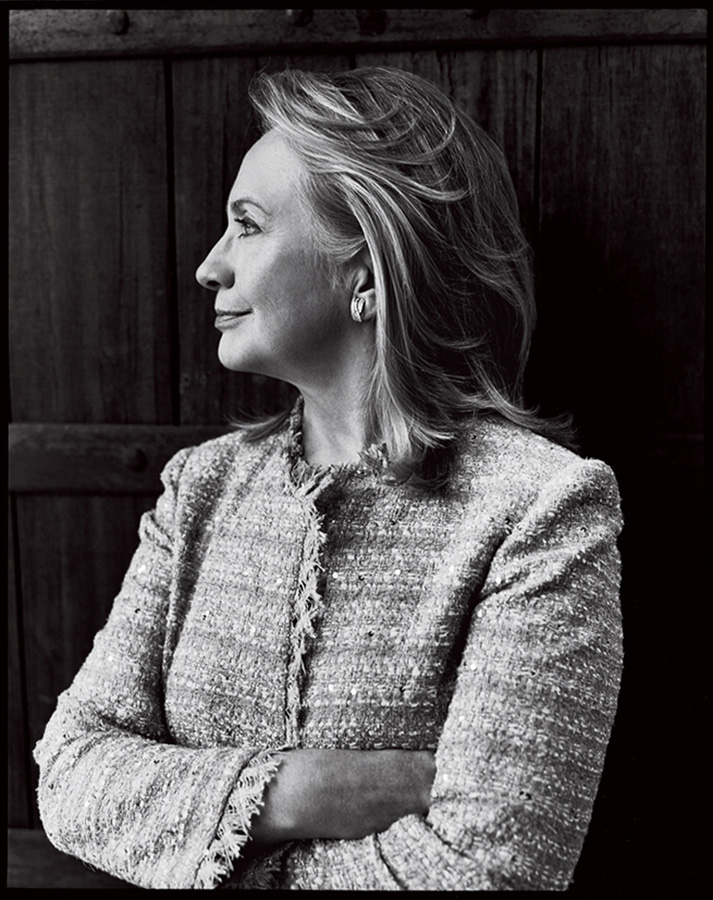

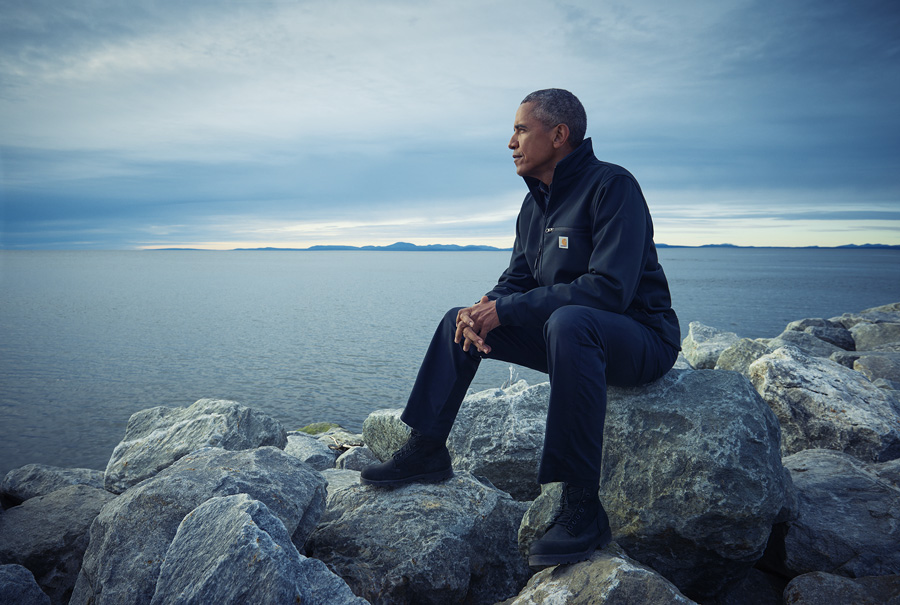

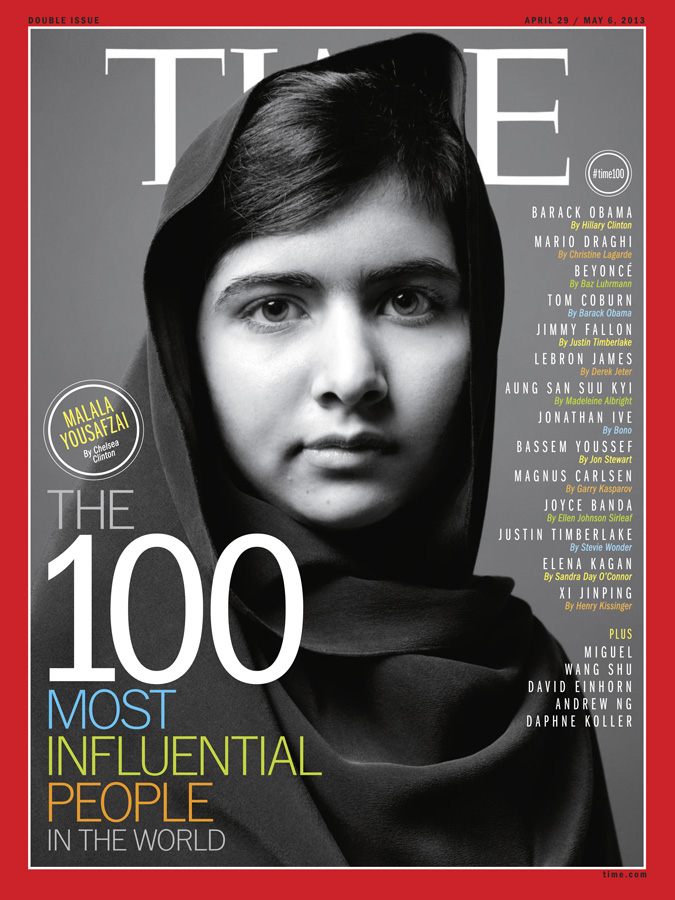

Mark Seliger is one of the best-known editorial portrait photographers in the U.S., for over thirty years. He succeeded Annie Leibovitz as the designated “chief photographer” for Rolling Stone Magazine and has photographed over 125 Rolling Stone covers. His magazine work in portrait and fashion continues to be extensive and includes: Italian Vogue, Elle, Vanity Fair, GQ, and others. He has won many of the top photo awards worldwide, and continues to create self-realized projects and endeavors. I had the opportunity to talk to Mark about his most recent personal project On Christopher Street: Portraits, which is being exhibited at the Von Lintel Gallery in Los Angeles.

Where did you grow up?

I was born in Amarillo and raised in Houston, and spent my high school years there. Later, I went to East Texas University and majored in photography and minored in graphic arts. After that I moved to New York to assist and ended up staying here.

How do you like Texas?

Texas is a great place. It has a really interesting balance of poetry and urbanness. Houston is very urban yet it gave me a lot of opportunity to grow up in the suburbs and see art, and experience life outside of Amarillo. I was really lucky that we were able to get out of town and have those experiences. And New York was the flip side of that because it’s a big little town.

Your parents are still there?

My father passed away. My mom still lives in the same house.

What was your exposure to photography before college?

In high school, I did a little bit of dark room stuff. I went to HSPVA, which was a magnet school in Houston. It was centered around media, video, television, and photography. The last year was more of a photographer apprenticeship. So I had quite a bit of photography background before college.

Who were your early influences?

My mentor was a guy named James Blueberry, who was our professor. Wonderful guy. I admired Penn, Avedon, and Arnold Newman was one of my heroes. I loved some of the early Skrebneski pictures and was a fan of Mary Ellen Mark and Diane Arbus.

Did you assist?

I assisted two years in Houston and about two and a half years in New York. I worked for John McDaire full time, and later several other photographers. Eventually I just decided to go out and do it on my own.

And you landed in New York around 1987?

I actually moved to New York in 1984 and apprenticed until almost 1987. I started to actively shoot towards the end of 1986.

Your first big break was shooting for Rolling Stone?

I started to shoot for a ton of different magazines. I ended up working for Rolling Stone pretty quickly. I was on retainer with them at first, and then eventually I went full time from 1992 to 2002, and then full time with Conde Nast (Vanity Fair and GQ) for ten years.

You have been moving into the fashion world a bit?

I don’t really consider there’s the one world or the other. As a photographer, your skill set travels everywhere. I mean I’ve done a lot of fashion stories over the years. I work regularly for Elle, Harpers Bazaar, Vogue, and Italian Vogue. We do a fair amount of that.

And you still do quite a bit with Rolling Stone to this day?

Yeah.

As for advertising work, do you find you enjoy it as much or less as editorial?

I enjoy taking pictures. If I take a job or assignment, I’m totally invested in it and excited whether it’s an advertising job or an editorial job. That’s why people hire me. They hire me to do what I do. That’s kind of the rule… If you’re going to take it, you have to thoroughly invest in it.

You are known for music. Has that industry changed a lot since you started shooting, or is there still a lot of work there?

The music world for me is very much an editorial experience. I do some record cover work and photographs for music packaging, whether it’s digital packaging, or a printed piece. But certainly we shoot a fair amount of artists for Vanity Fair, GQ, and some of the fashion magazines. So I think it’s very much alive and well. It’s obviously changing drastically with all these music services coming up. I still think there’s a lot of hope for interesting visual needs in terms of music and what is needed from that world.

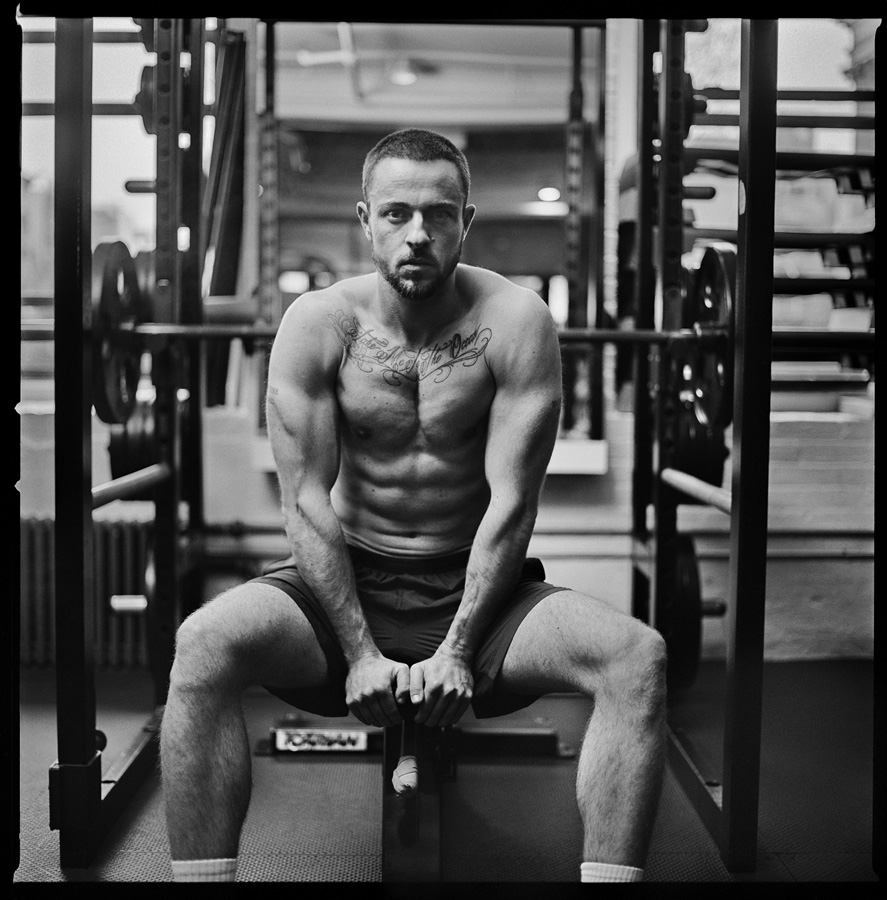

On Christopher Street was digital or film?

It was film, and everything was printed in silver gelatin process.

Do you print it, or do you send it out?

I work with a printer. I did not print this body of work, but I make initial tests myself. We worked with John Delaney, a wonderful printer who printed for Avedon at the end of his life.

Do you find it can be difficult working with publicists?

Do you find it can be difficult working with publicists?

I typically work one on one with artists. The publicists tend to make the connection between the artist and myself. And then usually we take it from there.

What is the gear you have used in the past and present?

We have a little bit of everything. We use everything from 8×10 large format to all types of digital and medium format. We don’t really use very complicated equipment. We use very simple equipment. That’s the name of the game. We use IQ, Phase One, as well as Nikons. But a fair amount of the fine art work that we do depends on what we’re going with for a particular project. For example, On Christopher Street, I tried a couple of different cameras, and I ended up going back to a Hasselblad and one lens. That’s usually how a project starts — just figuring out what is it going to be. Is it going to be Chinese? Is it going to be Japanese, who knows?

ISO?

We used Tri-x, always Tri-x.

400?

Yes.

A lot of your work is tack sharp. But that wasn’t the point with these?

No, these were on the street. We were moving in a quick pace. Sometimes it would be one roll of film. And sometimes it would be five rolls of film.

What did you use for lighting?

We used very little lighting. Mostly it’s just mineral lights.

ProPhoto?

No, just a little panel light.

Panel light?

LED.

LEDs. On battery or generator?

On battery. Everything was just portable so I can go out by myself or with an assistant. There’s nothing really fussy about any particular light. It was mainly the streetlight. It was meant to be fairly honest in terms of what we were doing, not trying to change anything. The theatre of it was really the point for me.

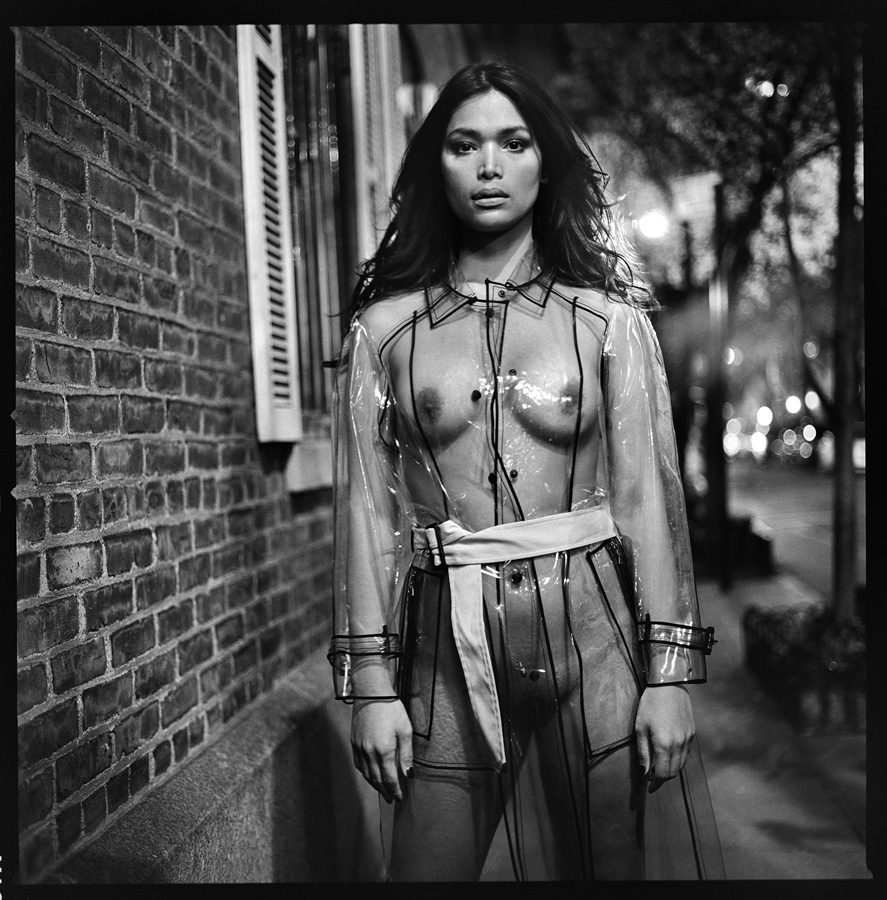

How did the idea for On Christopher Street come about? How did you find the subjects?

The process was really very simple; my neighborhood has been changing drastically and rapidly. Neighborhoods tend to vanish.

Where is your neighborhood?

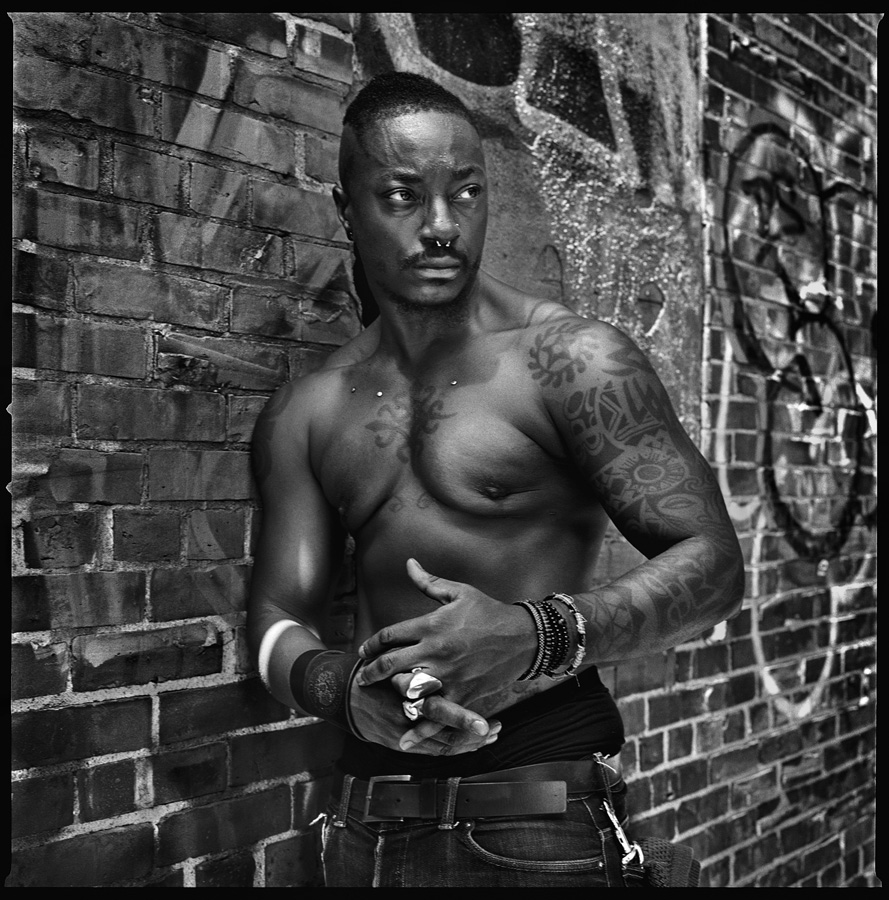

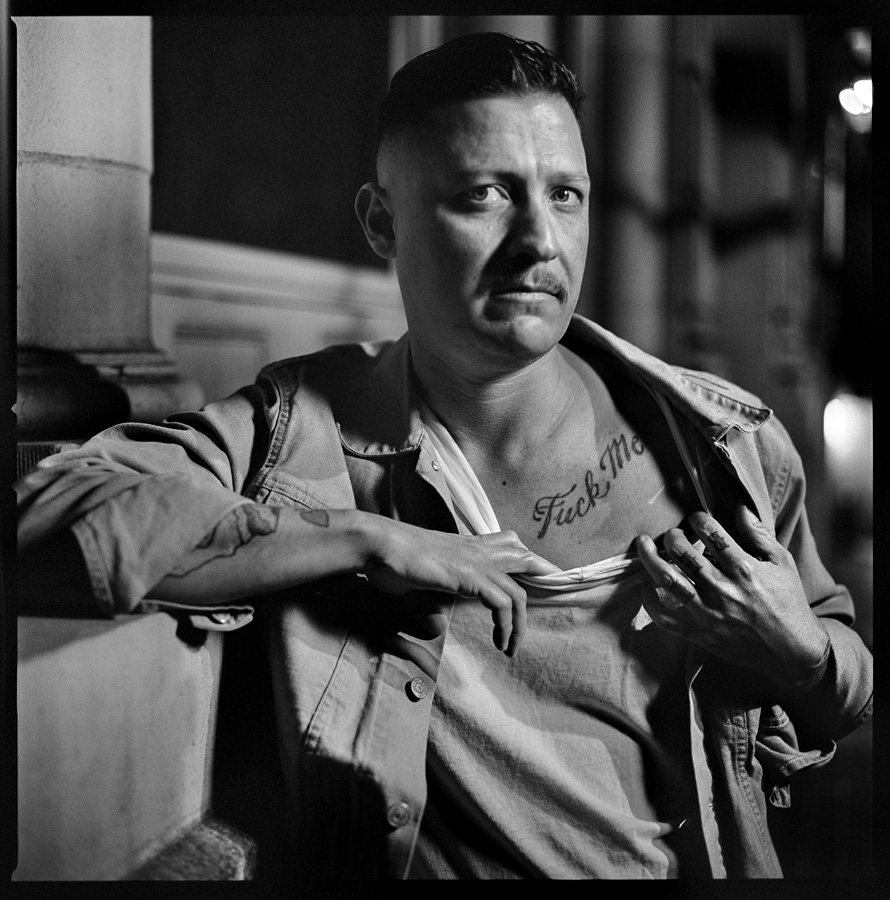

The West Village. I’m about two blocks from Christopher Street. And it was about going out and photographing people. There wasn’t a specific type of person I was photographing. It was just the theatre of the streets. After about a dozen portraits, we picked up on the fact that for most part, not all, it was mostly transgender.

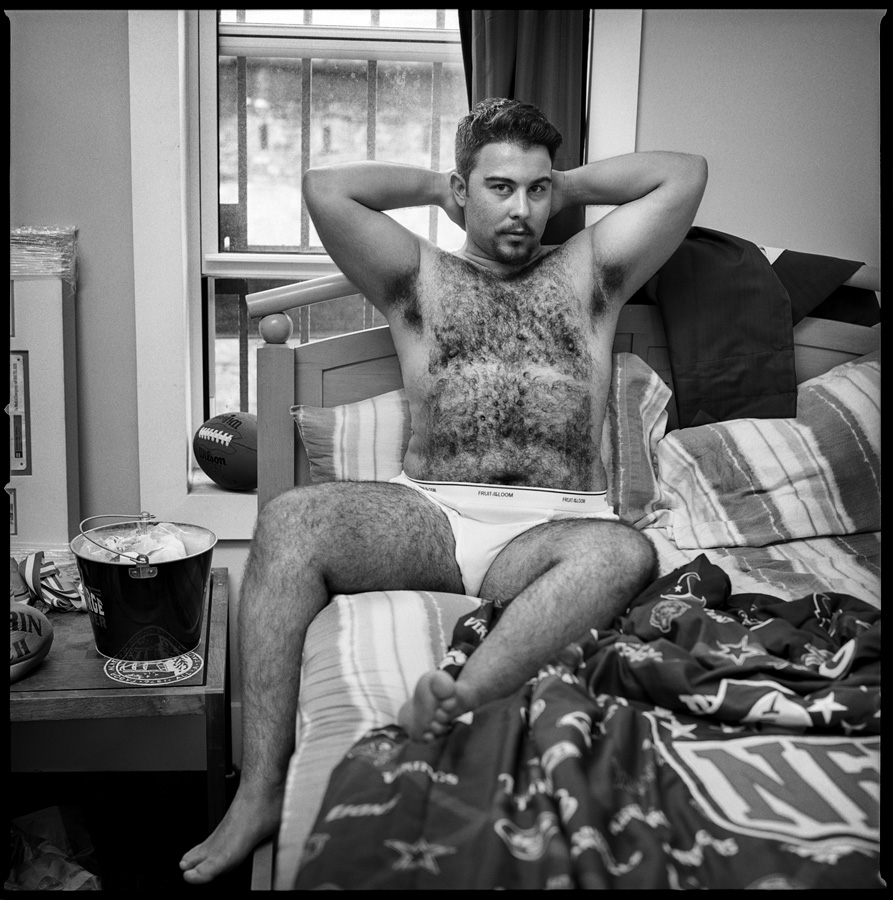

As we moved forward on the project, we used that as a base. Everybody that we would approach was in some form of transition. Some of them were occupationally working girls, and some of them were just people hanging out on the street. Eventually what happened after about the second year is we started to connect with a couple of folks that pointed us in the direction of the Transpanel. And when we went to the Transpanel, we met our guys. And that’s when everything changed. You really couldn’t spot Trans men on the street.

If you see someone who looks like a man, it’s a woman and vice versa?

Correct. It’s the exact opposite of what you imagine on the film.

And you also shot in their residences?

We only did a couple environmental portraits. That was just to show their lifestyle. For the most part we photographed people on the streets while walking around.

Did you cast anyone or just walk up and say hello?

The rule is that you have to go out and walk on the street and ask, and after a while, we had a couple of portraits that we could show and explain what we were doing — which was essentially going out and documenting the neighborhood. Eventually a friend of mine (who is very likable and easy- going — Frankie Marks) joined me and helped us find subjects. It was an evolution of how we wanted to work.

How important is fine art to your career?

Everything that we do is a trusted photograph and becomes part of the archive. There are some commercial jobs obviously that are not going to make it to the bank. That’s why I do so much editorial, because the editorial work is also a documentation of time. And this is somewhat of a responsibility of who I am as a photographer and an artist. I think those are kind of blurry lines. Obviously we know not everything is going to be considered art, but I’m an applied artist. For the most part, I work on a mission to do photographs. What I do for myself is not very far from what I do normally. I’ve always been one to have a project going at some stage. It’s really about evolving and finding new ways to tell the story.

What was the inspiration for you book When They Came to Take my Father – Voice of the Holocaust?

The inspiration for that was I grew up in Texas in a fairly modern Jewish home. We were always taught about the Holocaust. It wasn’t until later I met the owners of a bakery called ‘Three Brothers Bakery’, of which all three brothers were survivors. My friend was the son of one of the owners, and he introduced me to his dad. I saw the tattoo on his arm and remembered what an impression that had on me. Once I had the ability to actually generate a project on my own, we found publishers that were interested. I then partnered with writer and researcher Leora Kahn on telling fifty stories. It really became a fairly obsessive project. For a kickoff book project, it was wonderful. And it still has a lot of weight because some of those last stories were maintained and passed on later. A lot of these people have passed away, and they’re going fast. And the ones that I had an opportunity to photograph, for some of them, it was the first time they actually told their story.

We were taken aback that they were so open. But it was a really great journey for me to be able to explore documentary the way I was exposed to it in college. It was very humbling to be entrusted by these people with their stories. It was very similar to what we just did with On Christopher Street — which was meeting people for the first time without any real connections — just recognizing that they were in some state of transition on the street and then getting to know them, even if that was just shooting a roll or two of film and then being able to interview them and hear their stories.

When They Came to Take my Father was multi-state or in one area?

New York, Washington, LA, and Texas.

You did a book on Cuba. What was the inspiration for that? And how did you like Cuba?

Cuba, oh those are my little books. Every couple of years during the holidays, we put together a little sixteen-page book. It’s usually found images in my archive. This particular book was seven days that I went and photographed in Cuba.

How was Cuba?

It was great. Everywhere you turn you photographed. We went there almost five years ago. It was a time when it was still kind of under lock and key. As you know the last couple years there’s been a lot of development. It’s gotten very touristy. But when we were there, it was a pretty empty lot — basically an open ground for great photography. In fact, we had to get special permission to photograph in some areas.

It was harder then than now probably.

Yes, much more difficult. But it was wonderful. My friend and his wife lived there part time, and they were super helpful in moving me around and getting me in certain places and photographing certain people that I wouldn’t have been able to photograph or meet. So they were great in terms of making it happen.

How did the Lenny Kravitz book come about?

Lenny and I have been working together for probably four or five years consistently before the idea of the book. It was really just from having worked with him over the years, and then we looked at the collection of photographs, and pitched it to Arena books. Since then, our friendship continues and Lenny is actually taking pictures himself now.

He had Leica exhibition.

Yeah.

And you play music too. You have a band.

I have a little country band, yeah. It keeps me out of trouble.

Finally, how do you like New York City? You’re still living there? What do you like best or least about New York?

I love New York. Being in New York is a great place. Living here is easy in a lot of ways. It’s more accessible than anywhere else I’ve ever been. There are some advantages to obviously being in sunny California. We work there a lot. We have the opportunity to travel back and forth, and enjoy the beautiful weather and the different landscapes. But New York for me is where my studio is and the bulk of editorial is for me. So it makes a lot more sense for me to be here than to be anywhere else.

You used to live in LA too?

I used to have a little place to hang my hat there, but I no longer do. And I am happy to be just in one place right now.

Ken Weingart has been producing interviews for his Art and Photography blog, and he has kindly offered to share a his interviews with the Lenscratch audience. Ken Weingart has worked and lived in New York City, Los Angeles, Italy, and Spain.

He has won numerous awards including being selected for the Communication Arts Photo Annual, and his editorial and advertising work has been widely published all over the world.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

One Year Later: Christian K. LeeJuly 20th, 2024

-

One Year Later: Nykelle DeVivoJuly 19th, 2024

-

THE CENTER AWARDS: FISCAL SPONSORSHIP: CAROLINE GUTMANMay 28th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Hugh Kretschmer: Plastic “Waves”April 24th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Richard Lloyd Lewis: Abiogenesis, My Home, Our HomeApril 23rd, 2024