América Latina Week: Misha Vallejo

This interview was written with the kind help of and in conjunction with Elena Gálvez Mancilla – Mexican historian and sociologist; a researcher on the Amazon and indigenous culture, interested in the image as a historical source, photography enthusiast and environmental activist. The post is featured in both English and Spanish. The Spanish version follows the English.

©Misha Vallejo

This is an important time to talk about the Amazon. On April 2020, there was a massive oil spill of approximately 15.000 barrels in the Coca River, Ecuador. This unforgivable crime was in the hands of oil companies and the lack of governmental response. It was well predicted that the construction of pipelines in this territory would cause serious erosion to the land and yet, through China’s financial aid, the government has caused an irreversible crisis. The largest oil spill in modern Ecuadorian history has affected 150 Kiwcha communities who have suffered terrible physical, psychological and spiritual consequences.

We are all going through difficult times, this pandemic has hurt millions of people. It would be unimaginable for some to think about suffering the loss of their loved ones, but it really is unimaginable that under Covid 19 circumstances the government regards their population’s survival and mode of living insignificant and worthless. This is the country’s reality. It is impossible to grow crops, hunt, fish or bathe if your water source is entirely contaminated. Ecuadorian lives are on the line, many indigenous communities are hungry and isolated.

This is a clear race issue, people who suffer the consequences of this catastrophe are not mestizos, they are not white, they are native populations. Even after the government’s irresponsible management, they did not inform these communities about the spills, leaving many with serious health conditions. Seven months have passed and the Ecuadorian courts have not yet taken action against this crime. Apparently, some lives are just not worth protecting.

I am very proud to introduce Misha Vallejo‘s work today. He comes from my very own country, Ecuador. With intimacy and humanity, he has portrayed Sarayaku, the guardians of the Amazon. He has shown me and many others, that everyone’s life is connected to an important environmental reality and that caring is the only answer. Secret Sarayaku is currently on display at the Centre of Contemporary Arts in Quito.

Misha Vallejo is a visual artist and audio-visual storyteller whose work lies in the border between documentary and art. In 2014 he completed his MA in Documentary Photography at the University of the Arts London.

Among other distinctions, he won the 2020 Documentary Production Funds of the Ecuadorian Institute of Cinema and Audiovisual Creation for his first documentary feature film. Also, he has won the Goethe Institut and Prince Claus Fund for Cultural and Artistic Response for Environmental Change (Germany & Netherlands, 2018), the Photo Europe Network Prize at the PhotOn Festival in Valencia (Spain, 2018), he was selected for the Docking Station artist-in-residence program in two occasions (Netherlands, 2019 and 2020) and won the Ecuadorian National Arts Prize Mariano Aguilera (2015).

In 2016 he published his first photobook Al Otro Lado (Editora Madalena, Sao Paulo), which was selected among the best author photobooks at the Rencontres de la Photographie festival in 2016 (France), obtained the only honourable mention at the prize Felifa-Fola (Buenos Aires, Argentina) and was selected as the best photography book in Brazil in that same year, among many other international distinctions. In 2018, Spanish publishing house RM released his second photobook Siete punto Ocho, which won an honourable mention at the contest Pictures of The Year Latin America 2019 and was featured at the Athens Photo Fest (Greece, 2019). Recently, the same publishing house released his third book Secret Sarayaku, which is part of a transmedia documentary project that also includes an interactive web platform www.secretsarayaku.net and an exhibition.

Among others, his personal work has been shown at the LUMIX Festival of Young Visual Journalism (Hannover, Germany 2020), Bronx Documentary Center (New York, USA, 2018), at the Rencontres de la Photographie Festival (Arles, France, 2018), at the Budapest Photo Festival (Hungary, 2019), at the International Photography Festival of Valdivia (Chile, 2019) and in several solo exhibitions throughout Latin America and Europe. His editorial and personal work has been published in such media like The New York Times Lens, VICE, GEO, Marie Claire, Esquire and many others. He has given talks and workshops in photography and audiovisual storytelling in Latin America and Europe, a highlight of which was his participation at the 3rd Latin American Colloquium of Photography in Mexico City, 2018.

Currently, he is based in Ecuador and works in film and photography throughout Latin America and Europe.

@mishavallejo

I feel comfortable navigating the documentary and artistic realms, sometimes mixing them in the same project. I am not a believer in photography as a single image or single truth. I am a believer in photography as a series or narrative that is capable of telling real facts or fictitious stories. Among all, the themes I am interested in revolve around the “lost person” and the “lost place” and I try to portray them from the inside, expressing my opinions and sensations through them. The issues that I have been working on throughout my career have to do with social and environmental concerns. The images that I choose in order to tell these stories have a very strong subjective load, so they cannot be described as being purely documentary, instead, they acquire strong authorial speeches.

Every project I embark on dictates the aesthetic path and the way to approach it in order to tell it more effectively. For each work, I explore new forms of the narrative without fearing experiments. For instance, Secret Sarayaku is a trans-media project that consists of a myriad of elements (web documentary, photobook, exhibition and podcast) that may be accessed individually, as well as in conjunction. Every element of this story tells it in a different way in order to grasp the complexity of the Kichwa worldview on which this project is based. – Misha Vallejo

How did you start doing photography?

I started late when I was 26. I was studying Research Design in Russia and I took a photography class and loved it. Prior to that, I had not thought about photography as a means to express what I wanted to say. Later, I was enrolled in a 2-year course on photojournalism and it gave me so many technical tools. When my course was ending, I started working on what I call my induction. I had to cover nocturnal events. I learnt how to work with light and to work with very little light too! Photography allows you to navigate dispair realities. I would cover events where I found the Russian oligarchy, meanwhile, I was working on a personal project with homeless kids for my series Inexistent People. Sometimes those worlds would come together.

¿What is the most important part of your practice and how do you develop your creative process?

Processes are generally slow and paused. Besides, I usually work on 2 or 3 projects at a time and they take time. Secret Sarayaku, my most recent project took 5 years, it started in 2015. I usually travelled to the Amazon for 2 to 3 weeks every year. Whenever I had the budget, I went back a few more times too. To me, the creative process is similar to a good drink; the more you let it age, the more interesting.

Once I arrived in Sarayaku, those photos were created from my core, my bowels and it was in my journey back home that I was turning my brain on and began deciding on the project’s topics. To organize it in such a manner helped with setting clear goals and from a practical point of view, it allowed me to gain the trust of the people who I was portraying. Further, it was not a short project, people saw that I constantly returned for a period of five years and that I was committed to my job and had a genuine interest in their community. We became friends, time allows the possibility of relations and the most intimate stories, the fear of the camera disappears.

What do you mean when you say that you turned your brain off? Recently, I read that Bresson spoke about how rationality in photography happens before and after the act of pressing the shutter. Thus, when you press the shutter, you shut your brain off as if in a Zen state of mind.

I determined my themes before arrival, but then I improvised, I was lead by my bowels and the light. If I found a dazzling light, I’d wait until something occurred. For me, photography is instinctive, editing is a process in which a lot of thinking takes place and that is the most time-consuming process.

Who are the artists that have had a strong influence on your work?

Vasili Kandinsky, when it comes to composition. I love composing an image. When I first started, I wouldn’t see people, but shapes that I could detach for composition purposes. This was always a very conscious decision. Kandinsky was a basic guide for street photography; candid everyday life shots that are charged with emotion, light and the moment itself.

However, when it comes to photography, I admire many Latin American Photographers. From Nicolás Janowski, Jorge Panchoaga to Yael Martínez. They achieve the removal of all boundaries between reality and fiction and it fascinates me, I am looking for that too. That happened with Secret Sarayaku, I was inspired by oral tradition and mythological creatures who protect the jungle. Yet, they are invisible. How can you photograph something that you cannot see but know and feel around you?

What inspires you about Latin America?

Stories, it may sound so cliché but I like not knowing what is reality and what is fantasy. I believe it has a lot to do with how we tell stories, with so many nuances. I have not had that experience anywhere else in the world. I remember that when working on projects for my Master’s Degree in London, I had difficulties bringing about projects. I once went to Brixton, to a Latino cafe where I found a mini Latin America. There were Ecuadorian waiters, Colombian cashiers and Brazilian butchers. So many stories to be told at once, they inspired me. Even more so, I have stood by ecological and social activism and I know that Ecuador has the stories I want to tell.

Elena: Misha, one of the ideas that caught my attention the most about your work is how it invites us to important encounters and shows us how the world is structured, subjected to dualities. That which is false, real, national, international, outside, inside, etc. It seems like these notions are lost in some indigenous communities and it is interesting to see how you have incorporated this in a visual and aesthetic discourse. In that regard, have you thought about the kind of relationship that you wish to establish between people from Sarayaku and the viewers?

First, it was a learning relation. As westerners, and I include myself, we have so much to learn from them. From the way in which society is organized, to the worldview that everything is interconnected. Therefore, if you damage anything, it will come back to you. We perceive this through climate change, it is affecting the whole world because every action has its reaction. They have been saying this for years and that is why I am interested in this philosophy in which everything is connected.

Another important goal was to show other communities around the world that there is a social struggle strategy/path such as the one in Sarayaku. I wanted them to be able to access the Secret Sarayaku website and perceive an example of how things might change if we disseminate an ancestral message through the internet and social media. To take from it whatever might be useful for their own reality.

Regarding the images’ authenticity, I like to start dialogues and be very critical of my colleagues about truth in photojournalistic images. Up to what point should we even create photographs? On the web, for example, we have not only presented photographs but statistics regarding indigenous populations around the world that are guarding our forests. We have also included quotes from the Kawsak Sacha (Living Jungle) declaratory – Sarayaku’s system of coexistence.

Precisely, the project is subject to the circulation of knowledge that most westerners will not have access to.

As a photographer, you are the one with the power to construct your subject and imagery through the camera. As you know, the Amazon is a very powerful symbolic western production. Since the arrival of the Spanish, many symbols have been placed over this territory. Namely, cannibalism and polygamy. Every auteur who enters the Amazon constructs otherness; be it for evangelization or civilizing communities, they have had an intervention from the west. How do you think your work contributes to the construction of otherness? How to critically address the fact that your gaze shows us the “other”?

Well, there are two important issues. First, I always clarify that my work is subjective, you can believe me or not and that is ok. My gaze is subjective, and I am showing how I perceive reality. Second, I try to create a dialogue with the community. In the book and website, I did not write any texts, they are all from Kawsak Sacha. It has been a means to present what they think about themselves, the world and the living beings that live there. We have also presented interviews with community members written by José Miguel Santi – Sarayaku’s head of communication. I like the fact that there are many, different perspectives so that there is a richer and more complete reality. We have also created access to a blog controlled by Sarayaku on our website.

I cannot deny that I had my own expectations and went to Sarayaku with an idea of what I wanted to photograph. Nevertheless, they dissipated upon my arrival; people did not use a blowgun to hunt, they used their favourite football team’s shirts and young people listen to reggaetón in their cellphones. Plus, they use the internet as a fundamental tool for the protection of their ancestral territory and the fact that they had free satellite internet connection really amazed me. I sought to photograph Sarayaku as I would like to be photographed, in a horizontal and intimate manner. I did not want to exoticise, I wanted to create a friendship and come very close to see what I’d be able to find. I found we had the same concerns, the same joys and in our parties, we’d dance to the same music. I wanted to portray them with honesty, I care for them, so I photographed with affection.

Yazmeen: Yes, I could feel the everyday life environment and I found myself in those portraits. They look so familiar, perhaps because of how we share moments through social media.

Your pursuit for images seems to be very intimate, it makes me think about the title you’ve chosen, Secret Sarayaku. Why did you choose that name?

Sarayaku is relatively known in Ecuador for its ecological activism and the protection of nature. However, it is not known worldwide. Sarayaku won a lawsuit against the Ecuadorian government before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights; they established how significant it is for the court to acknowledge the government’s fault in entering this territory for oil extraction. I found it very strange that Sarayaku was not well known. Lastly, there have been multiple circumstances in which foreign scientists and anthropologists have extracted knowledge from this community and have not given them any recognition in exchange. It took a while before I could hear about their knowledge and legends, to be able to understand this secret world, there is a mystery to the experience.

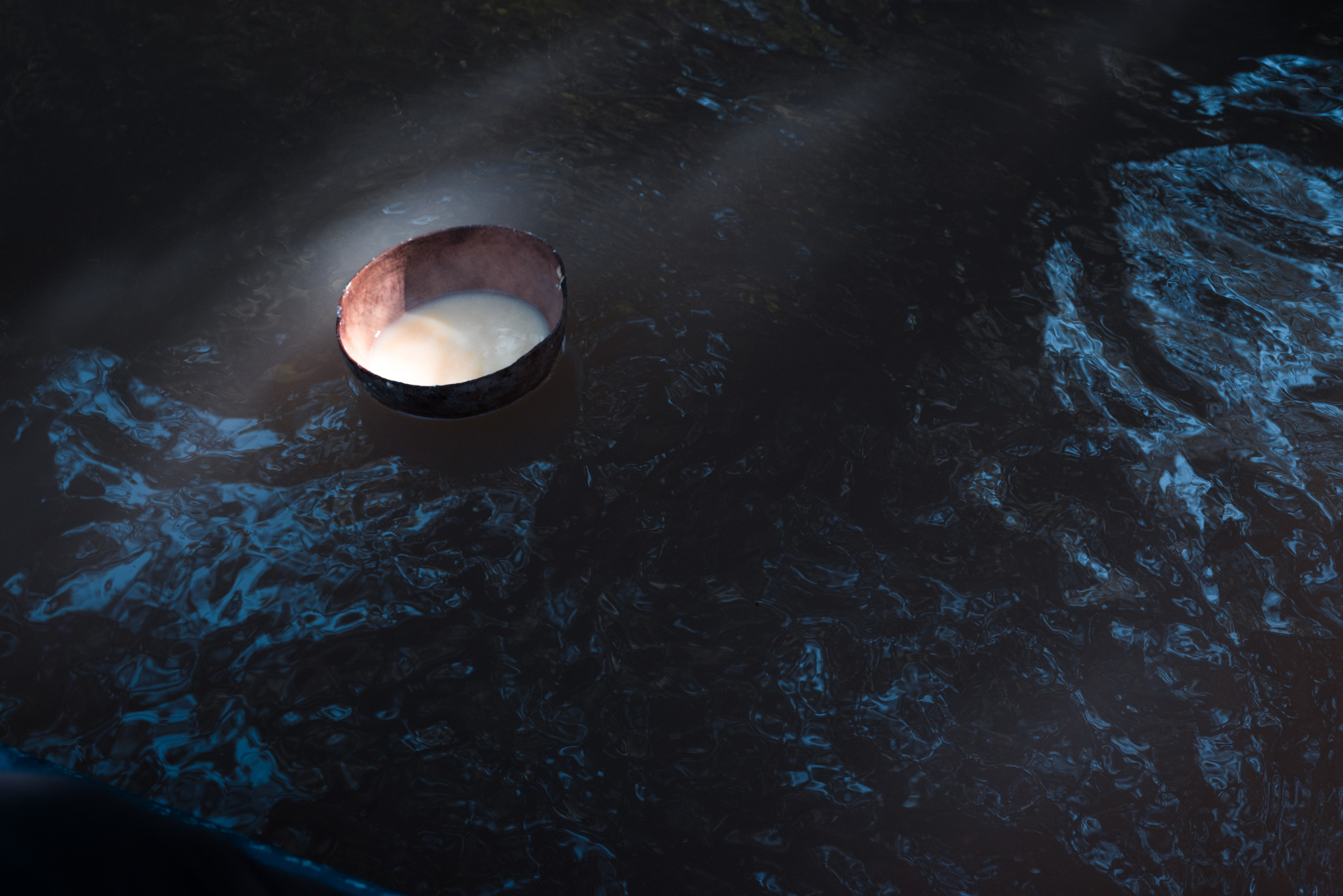

I love the photo that presents a holy “chicha”. I say so because it looks like if it were part of Rennaisance imagery, like when light flows on the inside of a church. Could you tell the story of how it occurred?

We were navigating the Bobonaza river, coming back from a 5-day hunt and our chicha was long gone. We found another boat and they were just starting their journey. These men had chicha and when you have chicha, you share it. They put it on a “pilche” (bowl) and it floated downstream. We were next to the shore, the light was beautiful, and that was the moment.

It caught my attention because of the eradication of chicha from our culture. After the arrival of the Spanish, there was so much publicity that showed it as the beverage of the devil, violence and stupidity – creating a very negative stigma about this tradition.

I am flattered by your interpretation. I had never seen it that way, but spectators are the ones who end up constructing the image.

ESPAÑOL

Esta entrevista se hizo con la amable ayuda de Elena Gálvez Mancilla. Historiadora y socióloga mexicana, estudiosa de la Amazonia y la historia indígena, interesada por la imagen como fuente histórica, amante de la fotografía y activista ecologista.

Es un momento idóneo para la hablar acerca de la Amzaonía. En Abril de 2020, se derramaron aproximadamente 15.000 barriles de petroleo en el Río Coca, Ecuador. Este crimen imperdonable estuvo en las manos de empresas petroleras y del gobierno Ecuatoriano. Se advirtió al gobierno sobre la erosión de la tierra si se procedía con la construcción de oleoductos en el territorio. Sin embargo, a través de financiación China, el gobierno ha ocasionado una crisis irreversible. El derrame de petróleo más vasto en la historia moderna del Ecuador ha afectado a 150 comunidades Kichwa, quienes han sufrido terribles consecuencias físicas, psicológicas y espirituales.

Todxs estamos pasando por tiempos muy difíciles, la pandemia ha afectado a millones de personas. Para muchos, sería inimaginable pensar en la perdida de sus seres queridos; pero es realmente inimaginable, que bajo las circunstancias de este virus, el gobierno actúe como si la supervivencia y el modo de vivir de su población no tuviera valor alguno. Esta es la realidad del país. Es imposible sembrar y cosechar, cazar, pezcar o bañarse con aguas completamente contaminadas. Existen vidas Ecuatorianas en riesgo, existen poblaciones indígenas que están pasando hambre durante el aislamiento.

Claramente, este es también un problema racial. Las personas que están sufriendo las consecuencias de esta catástrofe no son mestizas, no son blancas, son poblaciones indígenas. Incluso después de su manejo irresponsable del territorio, el gobierno no informó a las poblaciones sobre el derrame, dejando a muchos en condiciones de salud muy severas. Han pasado ya siete meses y la corte Ecuatoriana no ha tomado acción contra este crimen. Aparentemente, existen algunas vidas sin valor o derecho a la protección del estado.

Por ello, me llena de orgullo presentarles el trabajo de Misha, los dos venimos de Ecuador. Su trabajo fotográfico es íntimo y humano. En su último proyecto, Secreto Sarayaku, retrata a los pobladores de Sarayaku – los guardianes de la Amazonía. Misha me ha mostrado como la vida de todxs está conectada a una importante realidad medioambiental y que el cuidado de la misma es la única respuesta. Secreto Sarayaku se está exhibiendo en el Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Quito.

Misha Vallejo es artista visual y narrador audiovisual cuyo trabajo se encuentra en la frontera entre el lenguaje documental y artístico. En el 2014 completó su Maestría en Artes en Fotografía Documental en la Universidad de las Artes de Londres.

Entre otras distinciones, ganó el fondo de producción de largometraje documental del Instituto de Cine y Creación Audiovisual para la producción de su primer largometraje documental (Ecuador, 2020). Además, ganó la beca del Prince Claus Fund y Goethe Institut para Respuestas Culturales y Artísticas al Cambio Climático (Holanda y Alemania, 2018), ganó el premio Photo Europe Network del Festival PhotOn de Valencia (España, 2018), ha sido seleccionado para la residencia artística Docking Station de Ámsterdam en dos ocasiones (Holanda, 2019 y 2020) y ganó el Premio Nacional de las Artes Mariano Aguilera (Ecuador, 2015).

En el 2016 publicó su primer fotolibro Al Otro Lado (Editora Madalena, Sao Paulo, Brasil), el cual fue seleccionado entre los mejores libros de autor del festival Rencontres de la Photographie (Arles, Francia, 2016), obtuvo la única mención de honor del premio Felifa-Fola (Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016) y fue seleccionado como el mejor libro de fotografía de Brasil de ese año, entre muchos otros reconocimientos internacionales. En el 2018 publicó su segundo libro Siete punto Ocho (RM, Barcelona, España), el cual obtuvo una mención de honor en el concurso Pictures Of The Year Latinoamérica 2019 y fue expuesto en el Athens Photo Festival (Grecia, 2018). Recientemente, la misma casa editorial publicó su tercer fotolibro Secreto Sarayaku, que es parte de un proyecto transmedia que también incluye el documental web interactivo www.secretosarayaku.net y una exhibición.

Su trabajo personal ha sido mostrado en el Festival LUMIX para Periodismo Visual Joven (Hannover, Alemania 2020), en el Bronx Documentary Center (Nueva York, Estados Unidos, 2018), en el festival Rencontres de la Photographie (Arles, Francia, 2018), en el Budapest Photo Festival (Hungría, 2019), en el Festival Internacional de Fotografía de Valdivia (Chile, 2019) entre otros. Además, su trabajo editorial y personal ha sido publicado en medios como The New York Times Lens, VICE, GEO, Marie Claire, Esquire y muchos otros. Ha dictado charlas y talleres especializados en fotografía y narrativa audiovisual alrededor del mundo, entre los que destaca su participación en el III Coloquio Latinoamericano de Fotografía (México, 2018).

Actualmente vive en Ecuador y trabaja en proyectos audiovisuales y fotográficos en América Latina y Europa.

¿Cómo empezaste a hacer fotografía?

Empecé tarde, a los 26 años. Estaba estudiando Diseño de la Información en Rusia y tomé una clase de fotografía y me encantó. Antes de aquello, no había pensado en la fotografía como un medio para expresar lo que quería decir. Después, me inscribí en un curso de fotoperiodismo que duró 2 años y me dió muchísimas herramientas técnicas y justo cuando estaba terminando mi curso empecé a trabajar en mi conscripsión, cubriendo eventos nocturnos. Con ello, aprendí a manejar la luz, a trabajar con poca luz. La fotografía me permitía navegar mundos distintos, en esta cobertura de eventos encontraba a la oligarquía Rusa y con el fotoperiodismo, paralelamente, hacía un trabajo personal con chicos sin hogar para la serie Gente Inexistente. Un par de veces esos mundos se unieron.

¿Qué es lo más importante de tu práctica y cómo se desarrolla tu proceso creativo?

Generalmente son procesos lentos y pausados, además, usualmente llevo 2 o 3 procesos paralelamente. Secreto Sarayaku, mi proyecto más reciente, me tomó 5 años. Empezó en el 2015, iba de 2 a 3 semanas al año y si tenía los medios regresaba otras más. Para mí, el proceso creativo se puede comparar con un buen trago, mientras más tiempo lo añejas, más lo dejas reposar, se hace más interesante. Lo que pasó fue que llegué a Sarayaku e hice fotos desde las entrañas y de regreso a casa encendía el cerebro y empezaba a tomar decisiones sobre los temas del proyecto. Organizarlo de esta manera me ayudaba a regresar con objetivos fijos y eso, desde el punto de vista práctico, me permitió ganar la confianza de la gente que estaba retratando. Además no fue un fotoperiodismo corto, la gente veía que yo regresaba constantemente por 5 años y que estaba comprometido con mi trabajo y mi interés por la comunidad. Incluso existen amistades, el tiempo posibilita las relaciones y las historias más íntimas, el temor a la cámara desaparece.

¿A qué te refieres cuando hablas de apagar el cerebro? Leí hace poco que Bresson hablaba de cómo el raciocinio en la fotografía se da antes y después, porque en el momento exacto en el que se toma la foto, apagas el cerebro, entras en un estado Zen.

Muchas veces determinaba temas antes de llegar, pero ya allí improvisaba, me dejaba llevar por las entrañas y la luz. Si encontraba una luz muy bella esperaba a que algo suceda. Para mí, la fotografía es algo muy instintivo, la edición es pensada y es en ese proceso en lo que más me demoro.

¿Quiénes son los artistas que más influencia han tenido en tu trabajo?

Vasili Kandinsky por sus composiciones, amo componer. Cuando empecé en la foto, no veía a las personas sino las formas que podía abstraer para la composición, tomaba esas decisiones de forma muy consciente. Fue una de mis guías básicas para la fotografía de calle; las fotos son cándidas, “everyday life” en las que tienes que agarrar el momento, la luz, la composición, la emoción… Pero en fotografía, admiro a muchos fotógrafos de América Latina; desde autores como Nicolás Janowski, Jorge Panchoaga hasta Yael Martínez. Ellos logran borrar la línea entre ficción y realidad que a mí me fascina y es lo que estoy buscando. Eso me sucedió con Secreto Sarayaku, tenía la influencia de las historias orales y de seres mitológicos que cuidan la selva pero no se los puede ver. ¿Cómo fotografías algo que no puedes ver pero que sabes que está ahí?

¿Qué te inspira de América Latina?

Lo que me interesa son las historias que hay aquí y puede sonar muy cliché pero me gusta la idea de no saber qué es fantasía y qué es realidad. Pienso que tiene mucho que ver con cómo contar las historias, con tantos matices, no he tenido esa experiencia en otros lugares del mundo. Recuerdo que para proyectos, para la maestría en Londres, me costaba mucho hacer trabajos. Una vez fui a Brixton, a una cafetería Latina donde encontré una pequeña Latinoamérica; con meseros Ecuatorianos, cajeros Colombianos y carniceros Brasileños. Todo aquello era tantas historias a la vez, me inspiraban. Además desde hace mucho he sido muy cercano a los activismos ecológicos y sociales y sé que Ecuador tiene todas esas historias que quiero contar.

Elena: Misha, una de las cosas que me llama la atención de tu trabajo es como nos invita a ver encuentros y como el mundo está estructurado en función de dualidades; lo falso, lo real, lo nacional, lo extranjero, lo de afuera, lo de adentro. Parecería que en algunas comunidades indígenas esa dicotomía se pierde. Es muy interesante como has logrado integrarla en un discurso visual, estético. En ese sentido, ¿Has pensado qué relación buscas establecer entre la gente Sarayaku y los espectadorxs?

Primero, una relación de conocimiento. Como sociedad occidental, y me incluyo, tenemos muchísimo que aprender de ellos; desde organización social hasta la cosmovisión de que todo está interconectado. Si algo es dañado, va a regresar y te va a dañar a tí. Creo que vemos eso con el cambio climático, que seguro que va a afectar a todo el mundo, toda acción tiene una consecuencia. Esto es algo que ellos van diciendo desde hace muchos años, por eso me interesa la filosofía de saber que todo está vivo y todo está conectado.

Otro objetivo importante, es que otras comunidades de otras partes del mundo vean la web de Secreto Sarayaku, vean la estrategia de lucha social de Sarayaku y puedan tomar de ella cualquier cosa que les ayude en su propia realidad. Es un ejemplo de que las cosas, quizá, puedan cambiar – diseminando un mensaje ancestral a través de un medio tan contemporáneo como el internet y las redes sociales.

En cuanto al realismo de las imágenes, me gusta mucho entrar en diálogos y soy muy crítico con mis colegas sobre la verdad en las imágenes del fotoperiodismo. ¿Hasta qué punto debemos crear fotografías? En la web, no sólo están las fotografías, sino también las estadísticas de poblaciones indígenas cuidando los bosques en el mundo. Además, también están citas de la declaratoria del Kawsak Sacha (Selva Viviente), el sistema de convivencia del pueblo Sarayaku.

Justamente el proyecto está en una dilogía en función de la circulación del conocimiento que la mayoría de personas occidentales no tiene acceso. Sin embargo, en cuanto a la criticidad de la construcción de la imagen, tu tienes el poder de construir un sujeto y un imaginario a través de la cámara.

La Amazonía es un espacio muy potente de producción simbólica de occidente. Desde la llegada de los peninsulares a la Amazonía, se han puesto sobre ésta muchos símbolos. Por ejemplo, el canibalismo o la poligamia. Por ello, cada autor que entra a la Amazonía va construyendo su sujeto de la alteridad; ya sea para que sean civilizados o evangelizados pero existe la intervención de occidente. ¿Cómo consideras que tu trabajo contribuye a la construcción del “otro”? ¿Cómo abordar de forma crítica el que tu mirada nos lleva a conocer al “otro”?

Bueno, existen ahí dos puntos importantes. Uno, que yo siempre aclaro es que mi trabajo es subjetivo; me pueden creer como no me pueden creer y está bien. Mi mirada es subjetiva, estoy mostrando como yo veo la realidad. Dos, lo que trato de hacer es formar un diálogo con la comunidad. Por ejemplo, tanto en el libro como en la web, no escribí ningún texto. Todos los textos son de la comunidad y de la declaración del Kawsak Sacha. Ha sido una forma de presentar lo que ellos piensan de sí mismos en el mundo, en la selva y de los seres que allí viven. Existen también entrevistas realizadas por José Miguel Santi, el jefe de comunicación de Sarayaku. Me gusta que existan varias miradas porque así se puede crear una perspectiva de la realidad más rica y más completa.

No niego que tenía expectativas, obviamente fui con una idea de lo que quería fotografiar. Sin embargo, se empezaron a disipar al llegar; las personas ya no usan cerbatana para cazar sino escopetas, utilizan camisetas de los equipos de fútbol, los jóvenes escuhcan reggaetón en sus celulares y eso quitó mis prejuicios. Además utilizan la internet como herramienta fundamental para la protección de su territorio ancestral y me impresionó que tengan una antena parabólica con conexión satelital, gratuita. En la página web, también está el acceso a un blog controlado completamente por la comunidad. Intenté fotografiar Sarayaku como quisiera que me fotografien a mi y a mi comunidad, de forma horizontal e íntima. No quería exotizar, quería crear una amistad, acercarme y ver lo que podía encontrar. Encontré las mismas preocupaciones que yo tengo, las mismas alegrías, en las fiestas bailabamos la misma música. Quise retratarlos de forma honesta y les tengo muchísimo cariño.

Yazmeen: Sí, encuentro mucha cotidianidad en tus fotos, esa actividad de presentar nuestro día a día en redes y me encuentro en esas imágenes que me parecen tan familiares.

Tu búsqueda de imágenes parece ser muy íntima, me hace pensar en el título de trabajo, Secreto Sarayaku. ¿Por qué decidiste ese nombre?

Es una comunidad relativamente conocida en Ecuador por su activismo ecológico y protección de la naturaleza. Sin embargo, no se la conoce a nivel mundial. Yo comentaba a la gente que la comunidad de Sarayaku ganó el juicio contra el gobierno Ecuatoriano en la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos; algo realmente relevante y significativo – el que una corte haya reconocido que el gobierno hizo mal al entrar a este territorio para la extracción de petróleo. Me pareció extraño que no se supiera suficiente sobre Sarayaku. Además, ya han tenido experiencias de antropólogos o científicos de afuera que han extraído conocimientos y no han cumplido con reconocimiento alguno para la comunidad. Tomó algún tiempo para que me cuenten sus leyendas y entender un poco más de ese mundo secreto, existe un gran misterio en esa experiencia.

Yazmeen: Me encanta la foto que nos presenta una chicha divina, parece parte de un imaginario visual renacentista, como cuando la luz cae al interior de una iglesia. ¿Nos podrías contar sobre cómo ocurrió?

Estabamos en el río Bobonaza, regresando de una cacería de cinco días y se nos había terminado toda la chicha. Nos encontramos con otro barco, ellos empezaban el viaje y tenían chicha y si la tienes, siempre la compartes. La pusieron en el pilche (cuenco) y se movió río abajo y dejaron que flote. Estabamos en la orilla, la luz era bonita y ese fue el momento.

Yazmeen: Me llamó mucho la atención debido a la erradicación de la chicha de nuestra cultura. Existió mucha publicidad con la que se creó un juicio negativo; se decía que era la bebida del diablo, que creaba violencia y entorpecía a las personas .

Me siento muy halagado por tu interpretación de la imagen. Yo no lo había visto así, pero claro, son los espectadores los que acaban de construir la imagen.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Review Santa Fe: Leslee Broersma: Tracing AcademiaFebruary 11th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Ilana Grollman: Just Know That I Love YouFebruary 10th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Julia Cluett: Dead ReckoningFebruary 8th, 2026

-

Review Santa Fe: Elizabeth Z. Pineda: Sin Nombre en Esta Tierra SagradaFebruary 6th, 2026