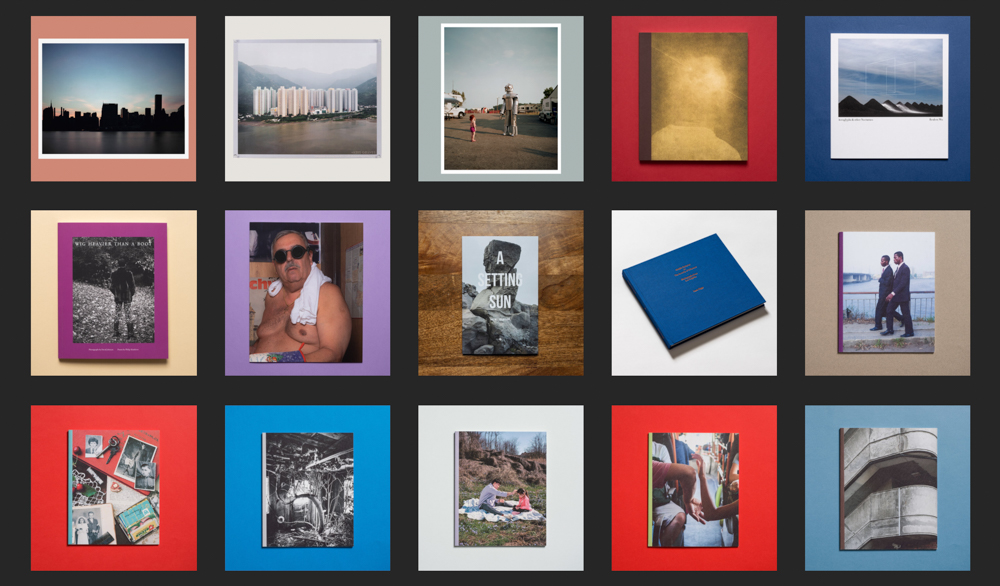

Publisher’s Spotlight: Kris Graves Projects / Monolith Editions

These past months we have been focusing on books on Lenscratch. In order to understand the contemporary photo book landscape, we are interviewing and celebrating significant photography book publishers, large and small, who are elevating photographs on the page through design and unique presentation. We are so grateful for the time and energies these publishers have extended to share their perspectives, missions, and most importantly, their books.

Kris Graves Projects collaborates with artists to create limited edition publications and archival prints, focusing on contemporary photography and works on paper that address issues of race, identity, equity, gender, sexuality, and class.

+KGP was originally founded as a gallery space in DUMBO, Brooklyn. In 2011, +KGP expanded into publishing, recognizing that books and prints have the unique ability to make fine art both accessible and affordable. We strive to expand the reach of artists, cultivate a new cohort of art collectors, and amplify stories that empower the long forgotten and underrepresented.

MONOLITH EDITIONS was founded by Kris Graves and is a Black-owned publishing house dedicated to showcasing work from artists of color across mediums that address issues of race, identity, equity, gender, sexuality, and class.

Today, photographer Kellye Eisworth interviews photographer and publisher Kris Graves.

Laura McPhee, Guardians of Solitude, 2015

What was the first book you published, and what did you learn from that experience?

I started thinking about publishing for the first time in 2009 after working with a friend who ran the publishing company Iris Editions to make an oversized, 16×20″ book with photographer Laura McPhee called Guardians of Solitude. I was running a gallery in Brooklyn at the time, but I realized I wanted to switch to books because it was an easier way for more people to own art. You know, a $40 book is easy to buy, versus a $2000 print that no one can afford.

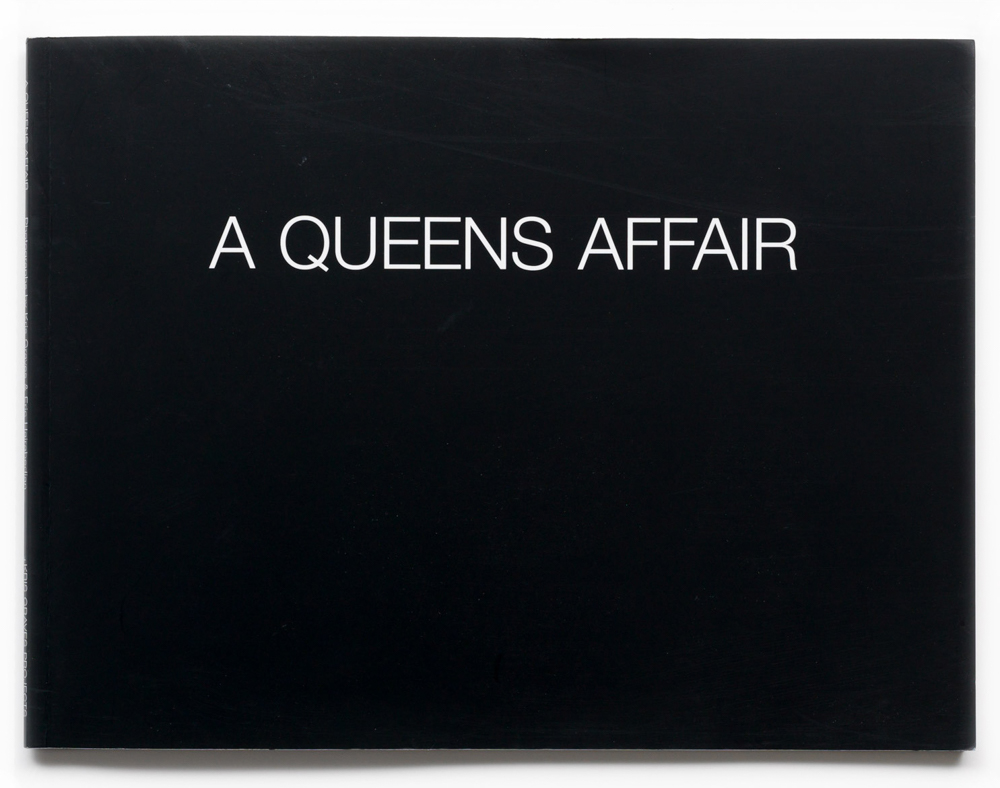

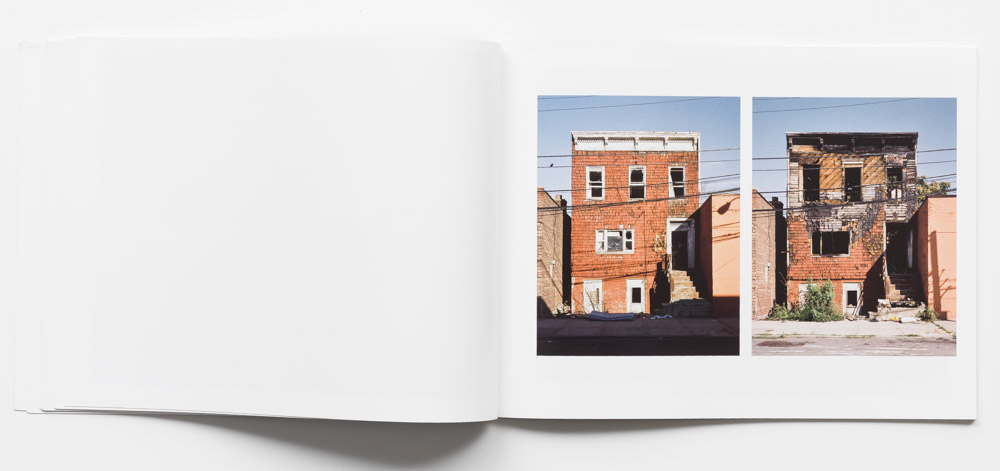

Kris Graves and Eric Hairabedian, A Queens Affair, 2010

The first book I published was a small soft-cover book called A Queens Affair, which included photographs of Queens by myself and a photographer named Eric Hairabedian. A few years after that I made two more expensive, hard cover books of my own work. Then I realized I wanted to make books with other people as well, so I switched the KGP brand over to publishing. We released the first books in January 2015 at the LA Book Fair and have made close to ninety books since.

Kris Graves and Eric Hairabedian, A Queens Affair, 2010

So it sounds like you got into publishing because you wanted art to be more accessible, and you felt like books were the way to do that.

Absolutely. The artists and I worked together; some came with their own designers, which is cool, but I acted as the designer for most of the early books. And we’ve just kept making books. We made about twenty-eight books in 2019; because of Covid we’ve made eighteen books this year, so it’s sort of felt like a year off.

Monolith Editions started around the same time the pandemic began and has already published about seven books. That press is devoted to people of color working in all artistic disciplines, not only photography.

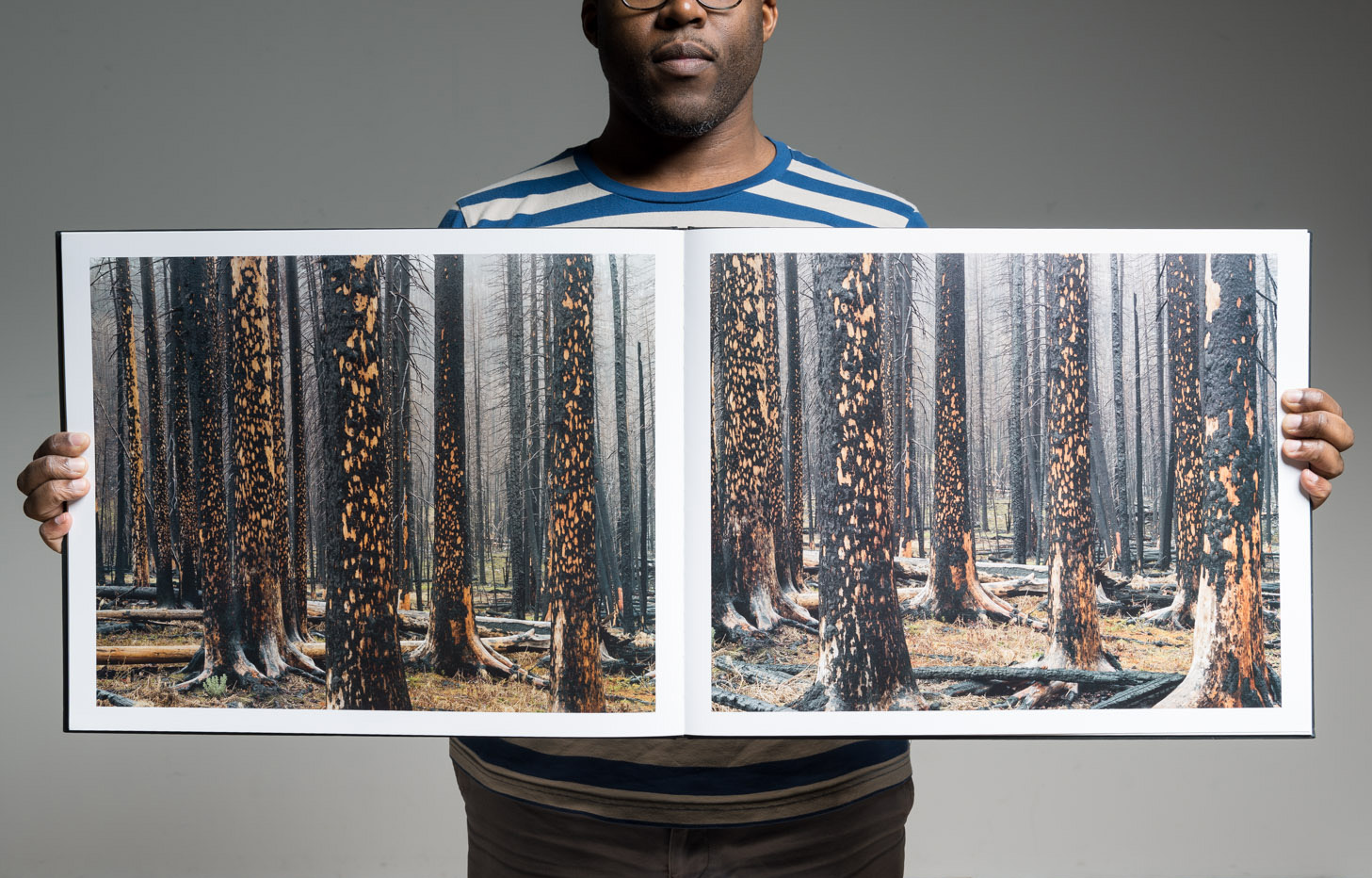

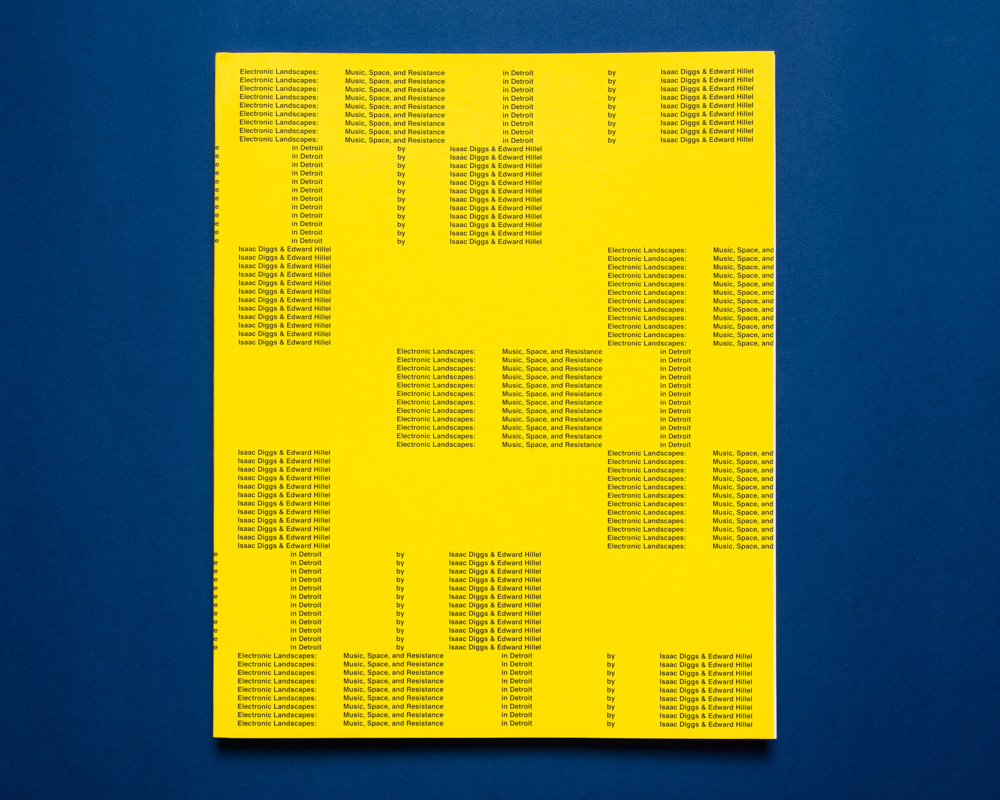

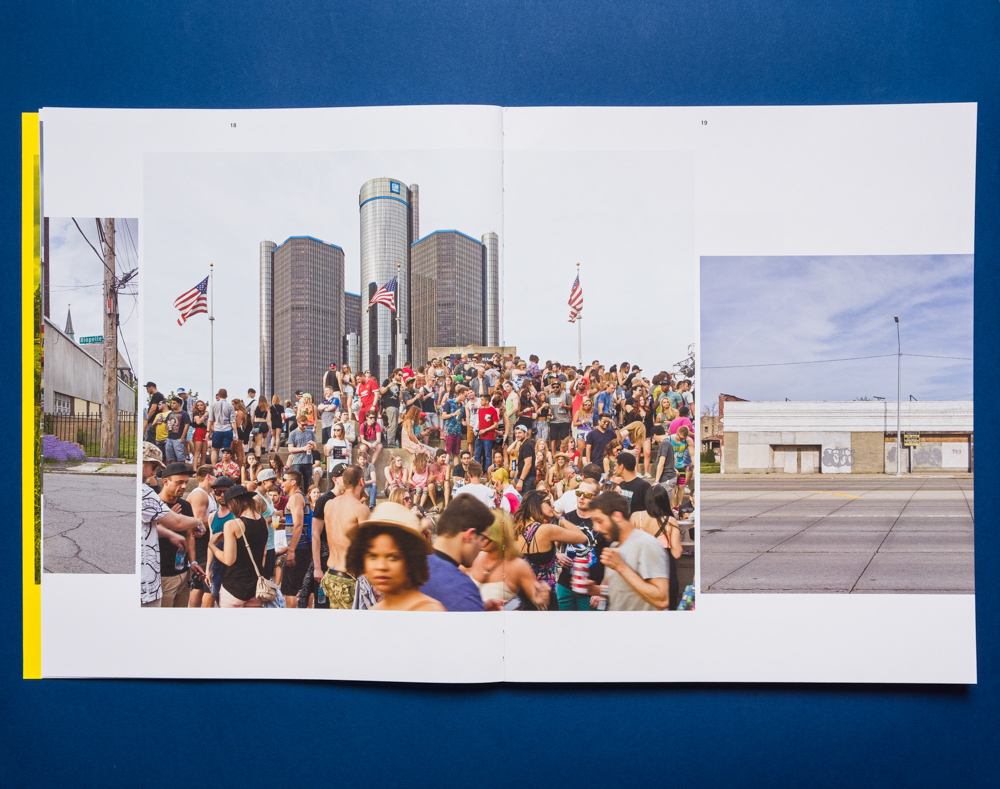

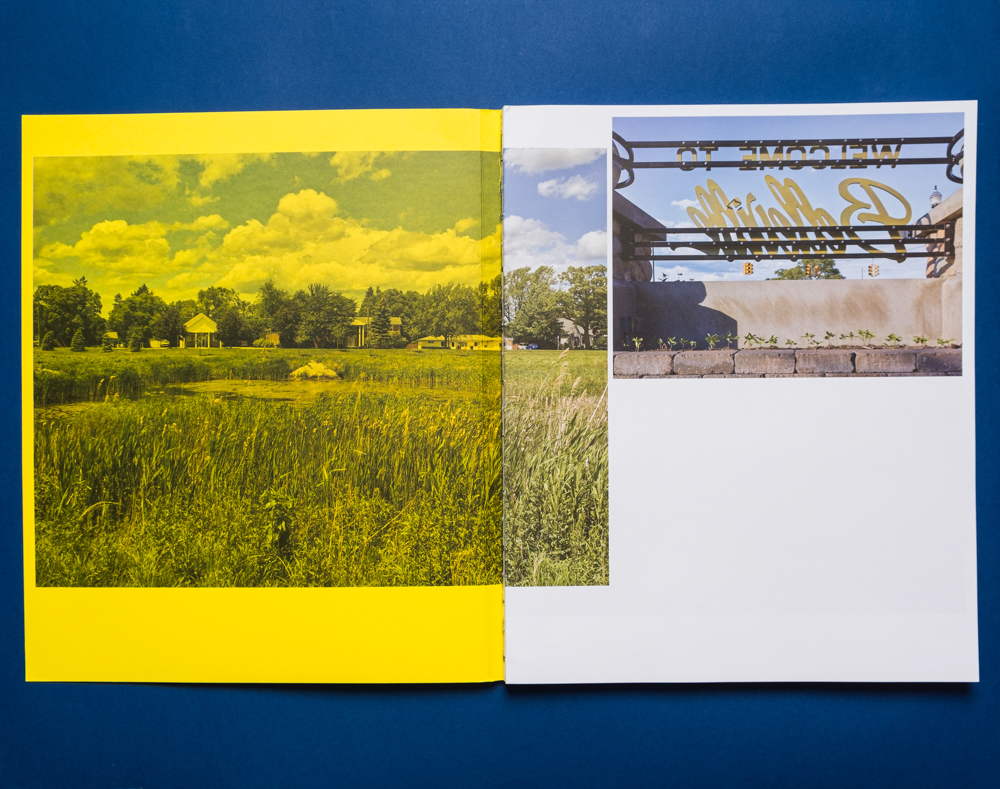

Isaac Diggs and Edward Hillel, Electronic Landscapes, 2021

Are there any publishing projects that have been particularly meaningful to you?

That’s a hard question because I love them all. But as the years go on, we hope to make better and better products. The latest book we made that’s starting to get some recognition is called Electronic Landscapes featuring photographs of Detroit’s electronic music scene by Isaac Diggs and Edward Hillel. It’s an amazing book, really big and designed very well. It’s up for Aperture’s 2021 PhotoBook Award. So that’s the biggest and newest thing, but I feel everything we make is better than anything that exists outside of our press.

Isaac Diggs and Edward Hillel, Electronic Landscapes, 2021

Do you think photographs communicate differently in a book versus on the wall?

Of course. For one, because you can look at a book anywhere- you can be at home, you can put it in your backpack and show it to your parents, you can send it to another country. You can never be inspired by something if you’re not with it; you can’t see a print once you leave your home, but with a book you can take it anywhere and be inspired. Books and photographers are made for each other because they also allow you to have the whole project as opposed to just one image. I mean, prints and books are both special, but I think books are more important than prints.

And make it accessible outside of the institutions of fine art

Yeah. Of course, the most accessible thing we have is the Internet. I mean, I think photographers should have all their stuff on their websites- not just a selection but the full series, because that’s really the only place for anyone to see them. Realistically, only 500-1000 people in the world are probably ever going to see your book, and maybe 300 people will see your work in a show. If you promote it on your website, hundreds of thousands or maybe even millions of people will see it. I think that sometimes artists want to be in the print world so badly they forget how enormous the world is beyond that.

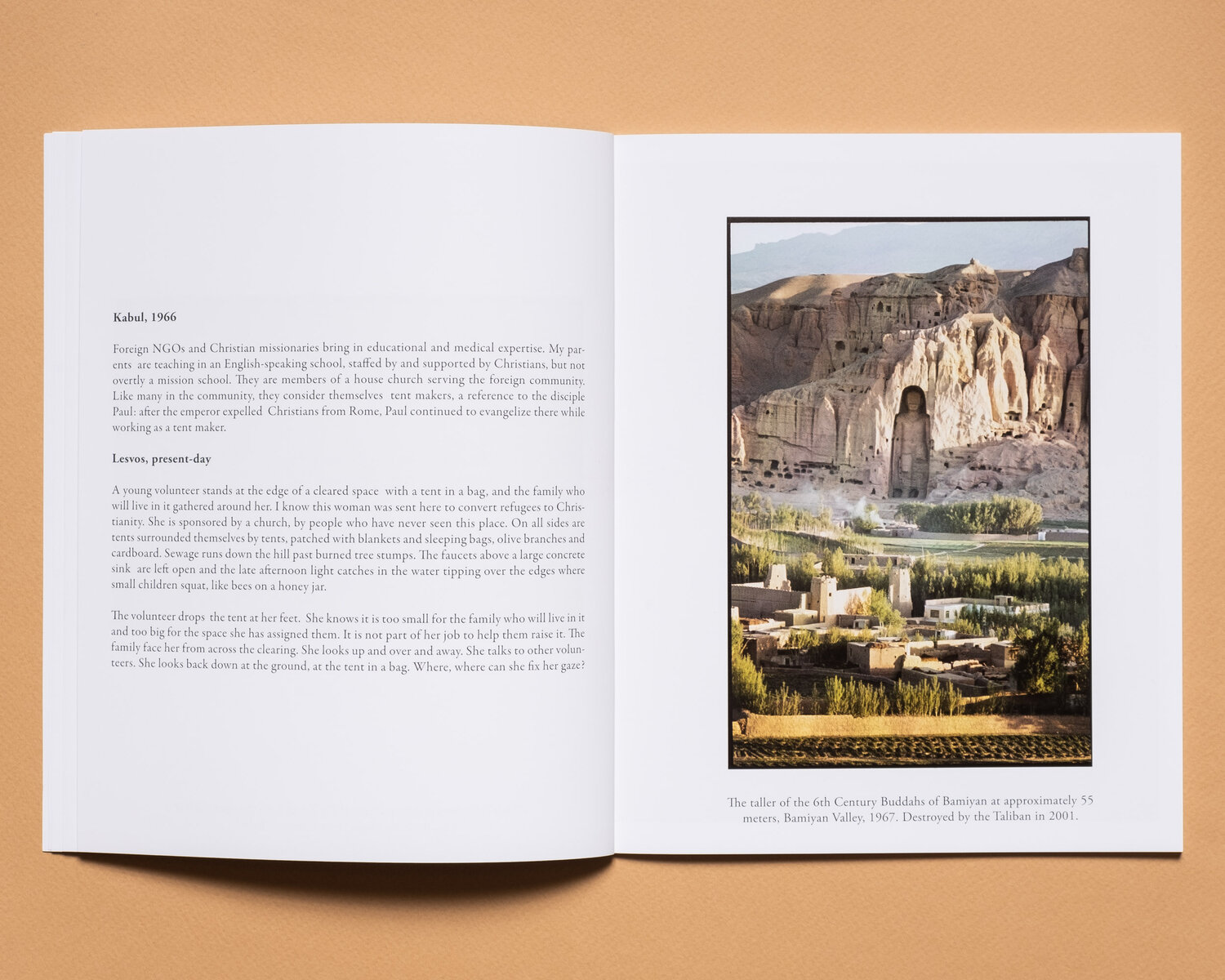

Kenneth Wrye and MaryLynne Wrye, Afghanistan, 1966-1974

How big is your organization?

It’s myself and a designer I work with often, along with the artist.

What is the typical timeline of a project, from the beginning to the finished product? How many books do you publish in a year?

Good question. They’re all different; I’ve been working on some books with friends for over a year now. I think everyone should allow for six months at a minimum, but I think that’s still tight. Usually, six to nine months would be a good amount of time to make a book comfortably. You can do it in less if you’ve already worked on the material and you have a designer lined up; you can probably get a book out in two months, but it will take another two months just to get the books from the printer.

I’ve been publishing for six or seven years and made about a hundred books, but over half of those have been in the last three years.

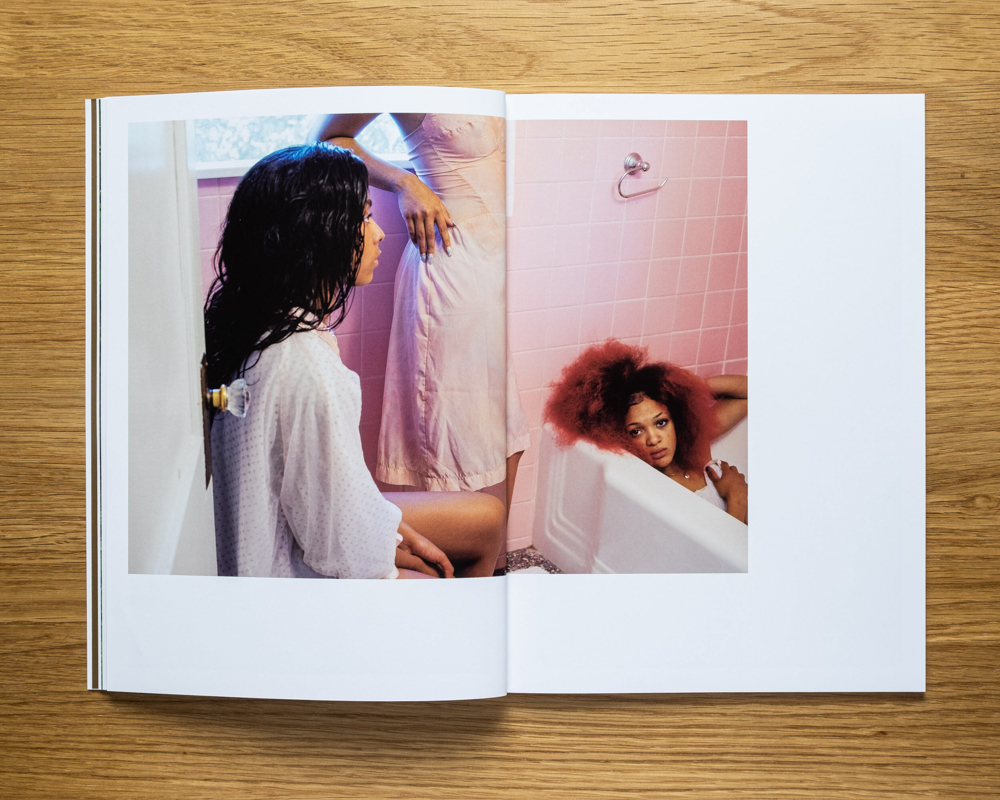

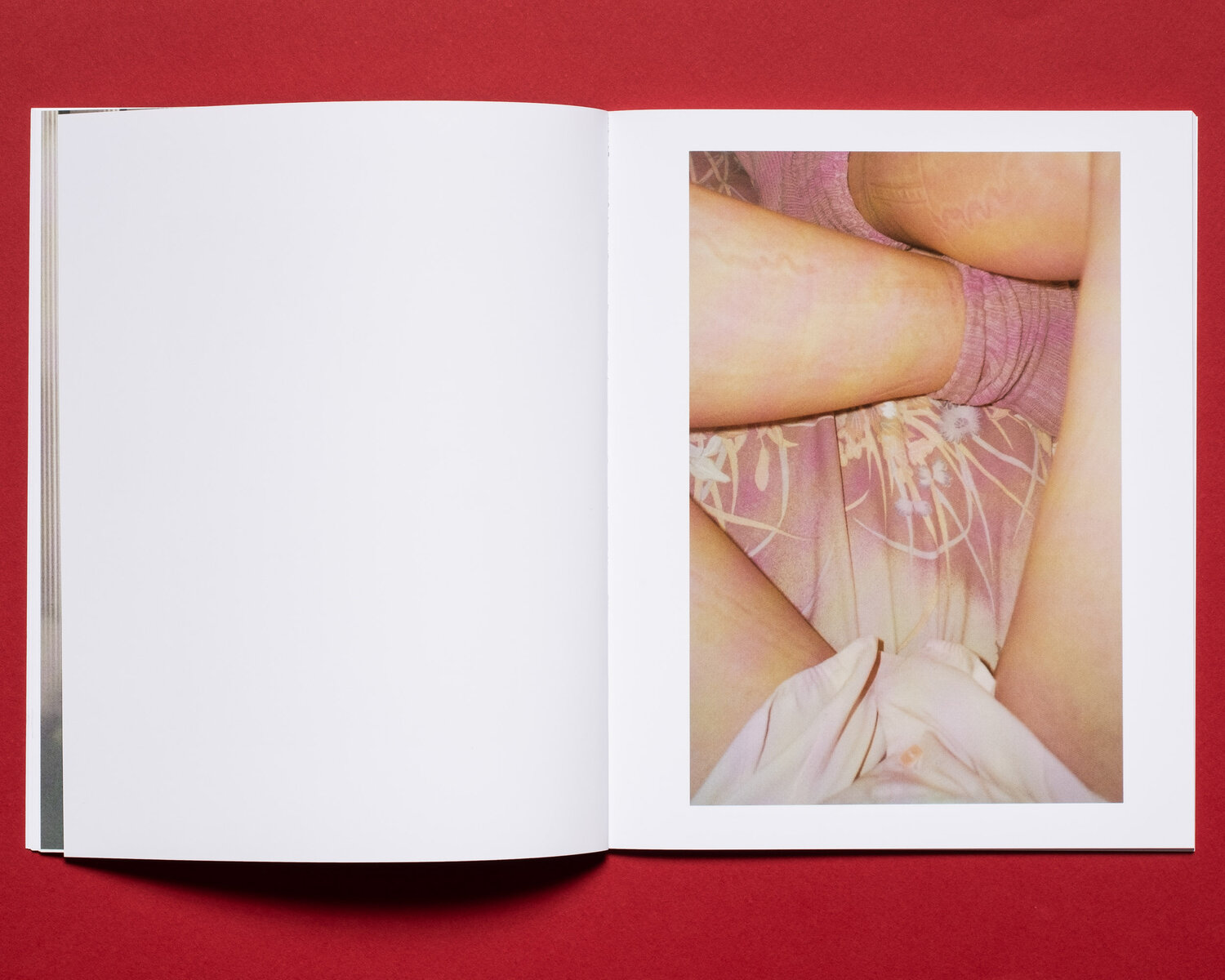

Nydia Blas, Revival, 2021

How can an artist get their work in front of you, and how do you choose which projects to publish?

We accept submissions, which I look over and hope to get back to you in a timely fashion. We get a lot of submissions, but I don’t work with people through submissions that often because I usually have a lineup of projects set a year or so in advance. But one of the projects I’m publishing in the next year did come from a cold email, so it does happen. It happens all ways- emails, friends of friends contacting me, or just seeing art that I really want to publish. I find art in a lot of different ways, but I’m the only person who chooses what we make.

So you also find art via exhibitions or Instagram, etc. as well- sometimes it’s you reaching out to the artist, not just the artist reaching out to you?

Correct, yes. I will definitely reach out to people if I want to make a book with them.

Isaac Diggs and Edward Hillel, Electronic Landscapes, 2021

How collaborative is the design process with the artist?

I usually have final say, but if an artist wants something really specific then we’re going to try and make it happen for them; that’s usually how we treat it. Artists are our only priority- that, and getting the books into museums and institutional collections. Everything else is kind of secondary to me.

Do you prefer artists come in with their own design ready?

No, that’s not necessary. It’s cool when it happens, but usually that’s not the case and that’s totally fine.

Tess Roby, Montreal

How is the financial side of the project structured between publisher and artist? Does the artist

contribute to production cost?

We only ask the artists to secure enough pre-orders so that we can cover production costs because we can’t really make books without pre-orders at this point. We can usually get at least 75% of the money through pre-orders. That doesn’t happen all the time, but if we get close enough I’ll just pay for the rest. Artists never pay for books unless they want something so special that we can’t afford to cover the cost.

What are some examples of things that would be considered special?

Most often it happens when an artist wants to use a specific paper that’s much more expensive, or if they want a hardcover book, which increases the cost of the book by $2000-3000.

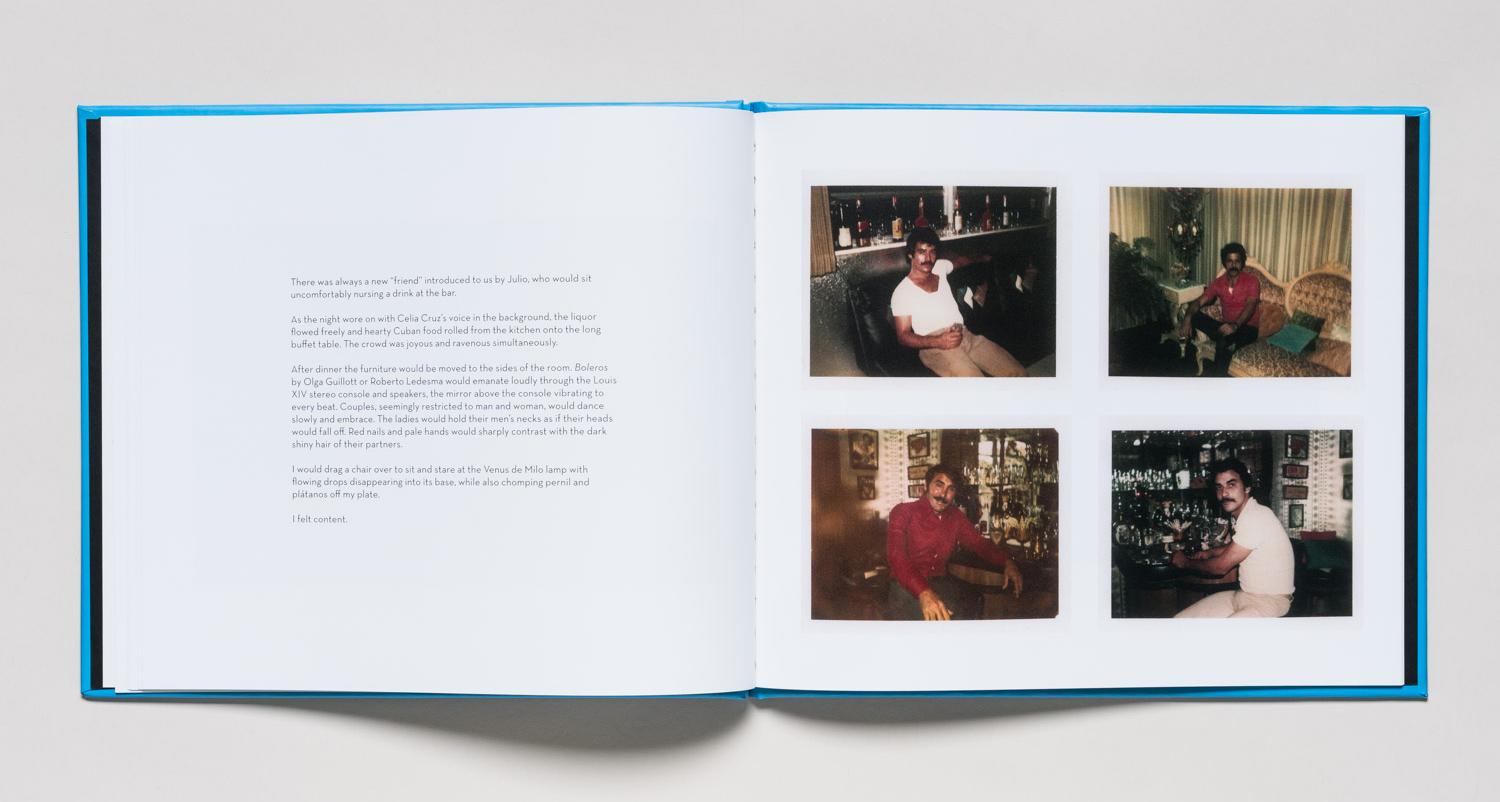

Orestes Gonzalez, Julio’s House, 2017

Is the size of the audience you think an artist can bring in terms of pre-orders one of the factors you consider when choosing what to publish?

Slightly, but not really. I try to focus on artists who are the best in the world. But, usually those artists don’t have a following like the most famous artists because the biggest artists are almost never as good as the smaller artists. If I like the work then I’m going to try and make it work, and usually if I like the work, a lot of other people already like the work. For example, if you have like five thousand followers, we’d have to imagine that at least fifty to a hundred people would buy a book. If it’s a small book and you sell it for $30, that’s about $1500. If you can sell ten prints at $200, that’s another two grand, so you’re getting close to making $3500 for the hundred or so books you sold. You’d probably need to sell double that for a larger book or a hardcover book, but that’s how it works in my mind. And if we can sell a hundred copies from an edition of three-hundred books during pre-order, it’s pretty likely that we’ll sell almost all of the books within a year or so.

How is that money divided between you and the artist?

The artist doesn’t make any money, but they get 10% of the books (i.e. if I make five hundred books I send the artist fifty copies as payment). Then I just pay myself back and pay for marketing. There’s really not much money in books. I’m actually not sure if we make a profit on anything; we don’t seem to be losing money on books, but I would be surprised if we made a profit on anything we publish. The artist pays for nothing, the artist is indebted to us for nothing. But we also don’t pay the artist, so it works both ways.

What support do you give artists in terms of marketing or distribution? Do you attend book fairs?

We have books in Photo-Eye or Printed Matter from time to time, but we don’t sell to bookstores and we don’t distribute anything. We make about three hundred copies of a book and aim to sell them all within a year or a year and a half.

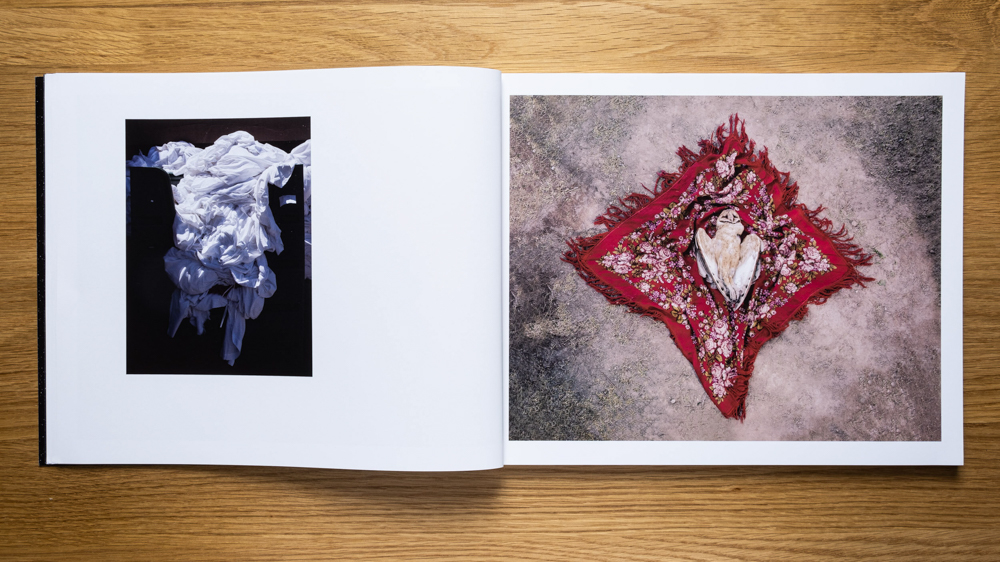

Hannah Altman, Kavana

Do you have any advice for photographers who want to publish a book?

Yes. First, make sure that you’re ready for a book- do you think your project is done and deserves a book? That’s important to ask yourself. Don’t rush it. If you can’t sell a hundred copies of your book by yourself then it’s going to be difficult for anyone else to sell, so I think everyone should build their own collector base first to see if there are enough people who will buy something. And then, you can either make it yourself- I actually think a lot of people should just be making their own books. I would say be careful with the presses if you’re trying to get into the book world because they’ll tell you they love your project and then try to charge you tens of thousands of dollars to produce a book. Personally, I wouldn’t pay any publisher $30,000 to make a book of mine. I don’t think there’s a return in that; I think I will try to find that return on the Internet instead. I mean, there are pluses and minuses to working with a publisher like that. If you’re good, it can get you a lot; if you’re not good, then you’ve wasted $30,000. So, you have to be ready.

Marshall Scheuttle, Morningstar

What are the difficulties publishers face?

It’s definitely not the easiest field; not many people buy books. The first book an artist publishes usually sells well; second and third books usually don’t, unless they’re just popular. The world exists as a popularity contest, and we choose to make books with people who are really great at photography but not necessarily popular. It makes it a lot harder for sales, but I also wouldn’t have it any other way.

Are there any upcoming projects you want to tell our readers about?

I have a set of two books of my own work dealing with landscape in America and the problems that exist in that landscape coming out at the beginning of the year. KGP will be releasing a book with Amy Elkins, and Monolith will be working with a UK-based photographer and poet named Marie Smith. Don’t miss these books!

Is there anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

You know, just that the artist and I work hard to make the books the best we can every time and we’re trying to bring you projects we really enjoy. I hope people take a moment to think about how much time and effort goes into it and support us by buying the books so we can continue to make more.

Follow Kris Graves Projects on Instagram: @kgpnyc

Follow Monolith Editions on Instagram: @monolitheditions

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: Smog PressJanuary 3rd, 2024

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: Kult BooksNovember 10th, 2023

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: ‘cademy BooksJune 25th, 2023

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: Brown Owl PressDecember 10th, 2022

-

Publisher’s Spotlight: DOOKSSeptember 26th, 2022