Thesis Project: Hugo Teixeira and Brandon Ng

©Hugo Teixeira, Chaparral A, April 2020

Anyone who’s done it will probably tell you that getting through graduate school is a challenge. For me, the period after graduating was just as difficult. Besides finding a job, I had to find a way to keep making work without the university’s facilities. I also had to figure out how to connect with the community outside of school, and I wasn’t really sure where I belonged. I think most people go through a similar experience after they graduate, and in our current moment that sense of uncertainty that comes with starting a new chapter in life- not knowing what the future looks like or your place in it– feels more relatable than ever. With the ongoing pandemic making financial resources more scarce while forcing the cancellation of the events that bring us together and the closure of the venues we rely on to exhibit our work, all of us- individuals and institutions alike- find ourselves charged with a similar task of carving out a place for ourselves in the world and finding a way to thrive in an unfamiliar, rapidly changing landscape.

I know I’m not alone in feeling moments of acute anxiety and despair about the challenges we’re facing. However, I also feel inspired by the way museums, non-profits, and individual artists are finding solutions to these limitations that actually expand our community and strengthen our connections. At Lenscratch, we created Thesis Project not only to give some members of our community who have been especially impacted by the pandemic an opportunity to share their work, but to facilitate a conversation about that community- what it means, what it looks like, and how it functions- in a time when supporting each other is more important than ever.

With this in mind, I would like to begin with the work of two artists who are exploring the ideas of place, community, and belonging in deeply personal ways. In Dog Days on the Chaparral and Lure of the Local(e), Hugo Teixeira and Brandon Ng use non-traditional methods of presentation to physically engage the viewer in their investigations of the relationship between location and identity in a way that feels dynamic and fresh. Although they look very different, both are a thoughtful reflection on the self.

©Hugo Teixeira, Chaparral A (detail), April 2020

Hugo Teixeira

Dog Days on the Chaparral

Dog Days on the Chaparral is an installation comprised of three photographic sculptures made in response to the question, “where are you from?” Although I define myself as both Portuguese and American, as someone who immigrated as a child, my identification as either ebbs and flows. The work embodies this slipperiness—a complicated emotional geography. To do so, I fabricate sculptures which collage images of two landscapes, the California chaparral and Portuguese montado, as proxies for these two homes and identities. I employ vernacular building materials, such as lumber and common fasteners, to create a literal and conceptual framework to which I affix an arrangement of contoured photographs. Hacking together disparate materials and technologies to create multi-layered sculptures reflects the Sisyphean efforts made to collage together a sense of home and belonging. The resulting photo objects are both visual and haptic and function as icons or shrines soliciting quiet contemplation of a place just beyond reach. When I contemplate these photo objects, I reflect on my family, our history, in this country and the old country, and collapse the distance between me and that narrative. Although the body of work is rooted in my idiosyncratic immigration experience, it reflects a wider migrant narrative. It may take generations for migrants and their descendants to feel grounded again when forces like poverty and conflict cause homes and nations to crumple like paper. –Hugo Teixeira

©Hugo Teixeira, Chaparral A (reverse), April 2020

Kellye Eisworth: In this time of social-distancing and greater isolation, how have you adapted your studio practice to the current situation, and and how is it impacting the work you’re making now?

Hugo Teixeira: We received news that RIT would be transitioning to a distance learning model during spring break. I was in the middle of production for my thesis show and I worked day and night knowing that I might not have access to the facilities after the break. Since then, I’ve still been working with landscape images, but I’m relying more heavily on digital manipulation and I’m experimenting with new ways of bringing 2D imagers into the third dimension. Right now I’m working with die cut paper and laser projection to achieve this. This will enable me to keep working until I can setup a personal studio again.

KE: As the traditional model of brick and mortar exhibition spaces become more difficult to sustain, both the arts organizations and the artist need to find solutions to sharing photographs. How best can an organization support the artist and visa versa?

HT: I think organizations can best support artists by tapping them into larger communities of artists and patrons. Organizations have a privileged position from which they can better survey the art landscape–certainly more so than young artists. As such they can connect individuals and groups with similar goals and interests quickly and effectively. In turn, artists can support organizations by volunteering to collaborate with their peers and serve in an advisory roll when needed. Low-residency art programs are pioneers in this respect and could serve as models.

©Hugo Teixeira, Chaparral B, April 2020

KE: How are you finding community (online and in person) in a climate in which we increasingly rely on digital platforms to connect with each other?

HT: I find that despite the relative ease afforded by digital platforms in communicating with other artists, a personal connection or recommendation is vital. To that end, I lean on the relationships I’ve established offline, with professors, peers, friends and others to open doors for me. Simply asking someone who knows me and my work, “who should I be talking to?” puts me way ahead. Of course, these offline relationships need to be cultivated with emails, chats, coffee, and help of all sorts–in short, building real relationships based in kindness and reciprocity.

KE: What are your thoughts on being a photographer today?

HT: I’m disheartened when I hear my colleagues and students, with their freshly minted BFA and MFA degrees, say they are uninspired to create new work in light of the pandemic. I have great sympathy, but I believe that work breeds inspiration, not the other way around. Being a photographer today might require more work than yesterday. We have to dig deeper to find that inspiration. I have no doubt that it is still there, waiting for us to uncover it by the sweat of our brows.

©Hugo Teixeira, Chaparral C, April 2020

Hugo Teixeira grew up in the Luso-American community in San Jose, California. A linguist by training, he studied photography at San Jose State University and Lisbon’s Escola Técnica de Imagem e Comunicação and is currently a candidate in the MFA in Photography and Related Media program at Rochester Institute of Technology. His artwork relies on photography, common materials, advanced technical skillsets and memory to create contemporary conceptual sculptures. As an artist and teacher, Hugo has exhibited work in the United States, Portugal, and the Macau Special Administrative Region of China.

Instagram: @hgtxphoto

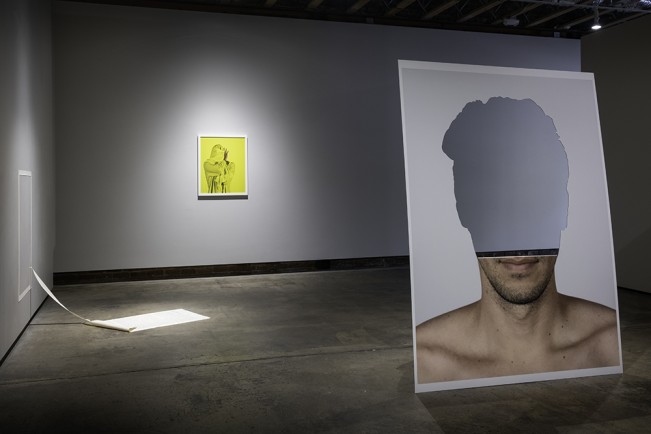

@ Brandon K.H. Ng, Lure of the Local(e) Installation, 2020

Brandon K.H. Ng

Lure of the Local(e)

Lure of the Local(e) investigates the complexity of belonging. Through the use of portraiture, object, and photographic sculpture, Ng considers the role of the settler, the citizen, and the human. Reflecting on experiences from his home in Hawaiʻi to the continental United States, the artist explores how land and place specificity affect individual and collective positionality. The exhibition’s title samples Lucy Lippard’s book “The Lure of the Local: Sense of Place in a Multicentered Society.” The text focuses on how the body connects to place by examining its relationship to history, geography, and culture. Ng’s remix of the show’s title includes the inclusion of an “e” at the end of local to call attention to the body and place specificity. Furthermore, it refers to “local culture,” a particular political and cultural identity marker in Hawaiʻi. This paronomasia acknowledges subversive notions of land passivity while activating critical discourse surrounding race, power, and settler colonialism. Lippard describes place having a particular pull, one that “operates in each of us, exposing our politics and our spiritual legacies. It is the geographical component of the psychological need to belong somewhere, one antidote to a prevailing alienation.” Ng’s work is a critical self-examination of the spaces where history and the body overlap. In doing so, the question he asks himself and his audience to consider is not if I belong, rather how I belong. – Brandon K.H. Ng

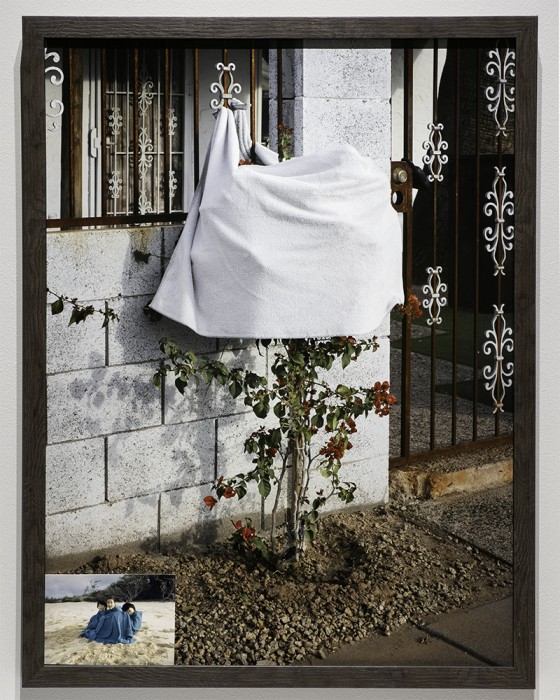

@ Brandon K.H. Ng, (Winter) Banana Tree (Summer) Banana Tree, 2019

Kellye Eisworth: In this time of social-distancing and greater isolation, how have you adapted your studio practice to the current situation, and how is it impacting the work you’re making now?

Brandon Ng: The short answer to this that I havenʻt adapted yet. At least not the physical studio work. Like most students, I was doing the mental preparation necessary to anticipate the loss of institutional facilities. When COVID-19 hit, that transition period went out the window. So, for now, I’m focusing on the administrative side of being an artist, which I consider an essential part of studio practice. I’m doing things such as updating my CV and website, searching and applying to open calls and residencies, and looking for jobs. Currently, I’m editing a video of this exhibition, which has not been easy because I know nothing about editing videos. But I’m learning things along the way, and it feels productive. And if it feels productive, I feel okay about it.

@ Brandon K.H. Ng, Aloha Wear, 2018

KE: How are you finding community (online and in person) in a climate in which we increasingly rely on digital platforms to connect with each other?

BN: I’m not that tech-savvy, so I rely on in-person interaction and engagement. Being in graduate school provided many opportunities to access the artists and thinkers brought in by the institution. These events are usually open to the general public, so keeping an ear to the ground for creatives coming to town is always a good idea. As I meet more people in the photography/art community, I began to realize that the art world is smaller than I initially thought. Chances are you know someone that knows an artist whose work you genuinely admire, and from that, you can make connections. I believe that is one of the lovely things about working within a creative field; by putting yourself out there, you will find those like minded people who share your passions and curiosities.

@ Brandon K.H. Ng, Lure of the Local(e) Installation, 2020

KE: What are your thoughts on being a photographer today?

BN: I think it’s exciting to be a photographer today. I mean, I assume it has been exciting to be a photographer from the beginning. It’s because this media is so alive, and is continuously evolving with every jump in technological advancement. We’re in a moment in our history where photography has infiltrated seemly all aspects of our lives. Just today, I was at an ultrasound and found myself talking to the doctor about how light and shadow were created from sound projections to make an image. It’s fascinating to me that this is just one out of infinite methods employed to create a picture. And perhaps this is where I accrue part of the motivation for my work. In this idea that boundaries of photography are challenged from both the position of necessity and curiosity to catalyze new ways to create and consume images.

@ Brandon K.H. Ng, Untitled, 2020

Brandon K.H. Ng (b. 1984, Honolulu, HI) received his BFA from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa (2012) and is currently completing the last year of his MFA at Arizona State University (2020). His photographic and installation works focus on the complexities of identity and place distilled through historical, social, and political systems.

Instagram: @b_kh_ng

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Earth Week: Aaron Huey: Wallpaper for the End of the WorldApril 26th, 2024

-

Earth Week: Casey Lance Brown: KudzillaApril 25th, 2024

-

Tara Sellios: Ask Now the BeastsApril 6th, 2024

-

ALEXIS MARTINO: The Collapsing Panorama April 4th, 2024

-

Emilio Rojas: On Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands: The New MestizaMarch 30th, 2024