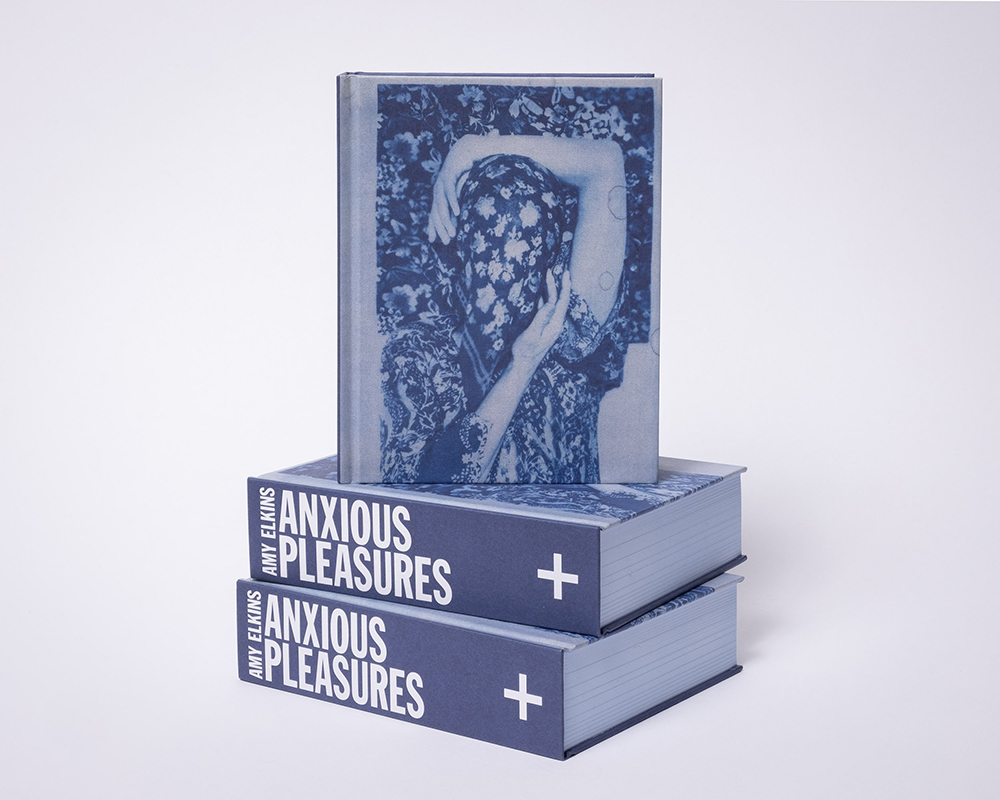

Amy Elkins: Anxious Pleasures

Amy Elkins’ second monograph Anxious Pleasures, published recently by Kris Graves Projects (+KGP), is the result of Elkins turning the camera on herself to make self-portraits everyday during the hardest part of the COVID-19 pandemic: 377 consecutive days in lockdown before reliable and regular testing or vaccination was available.

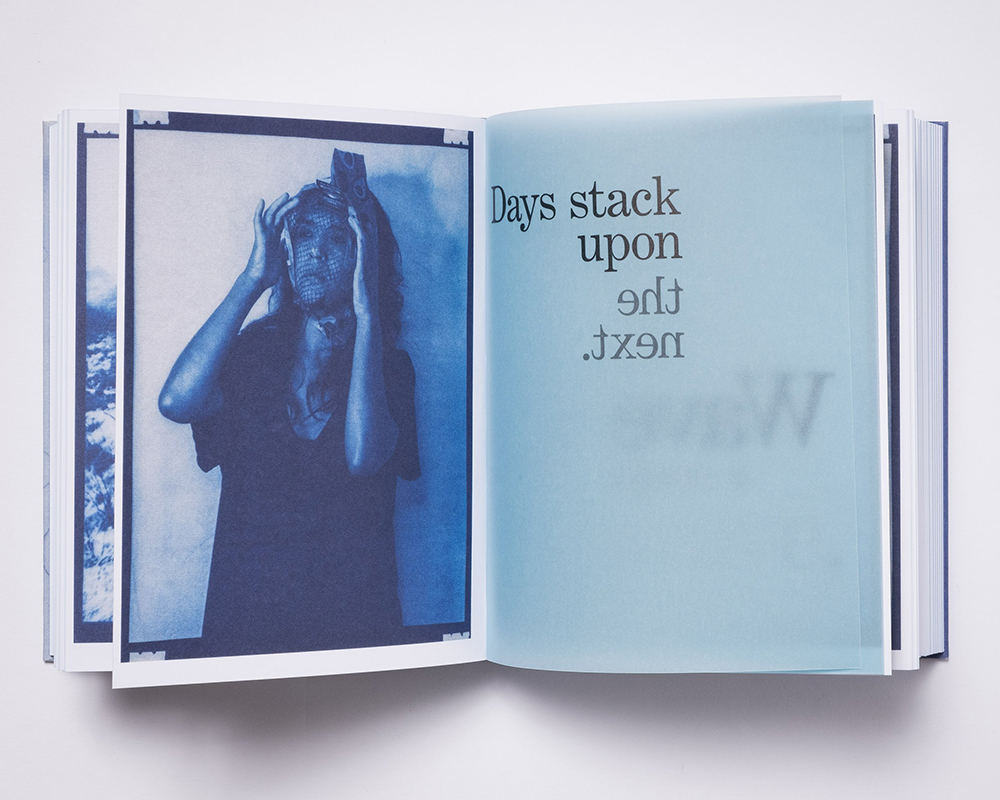

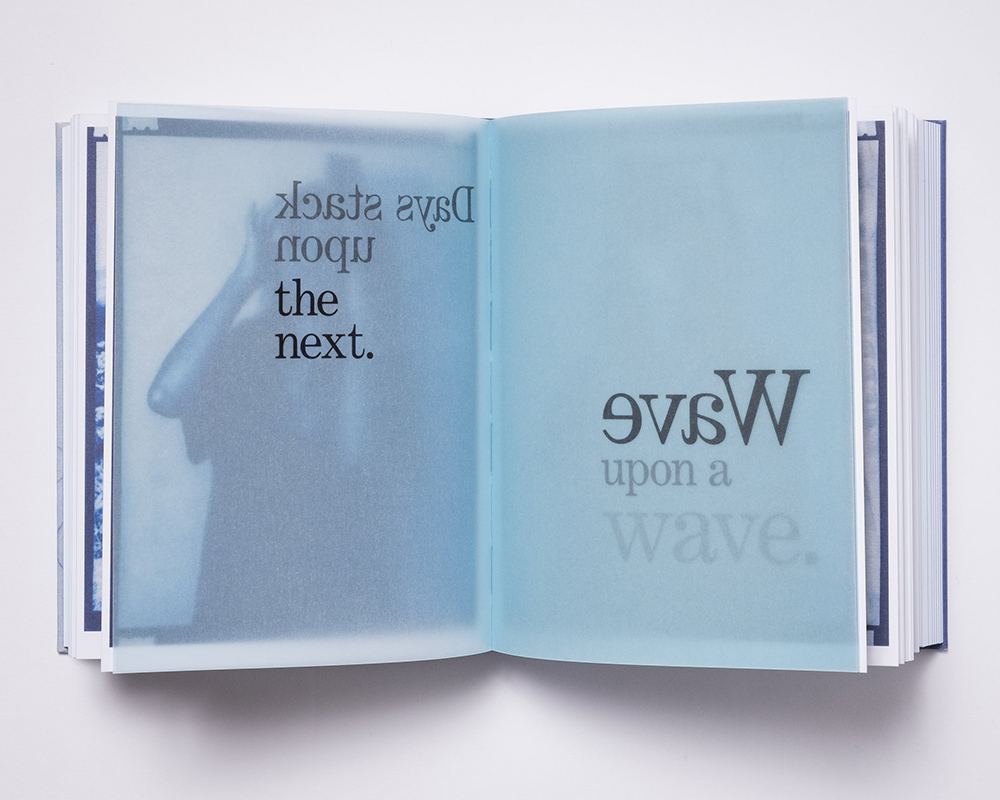

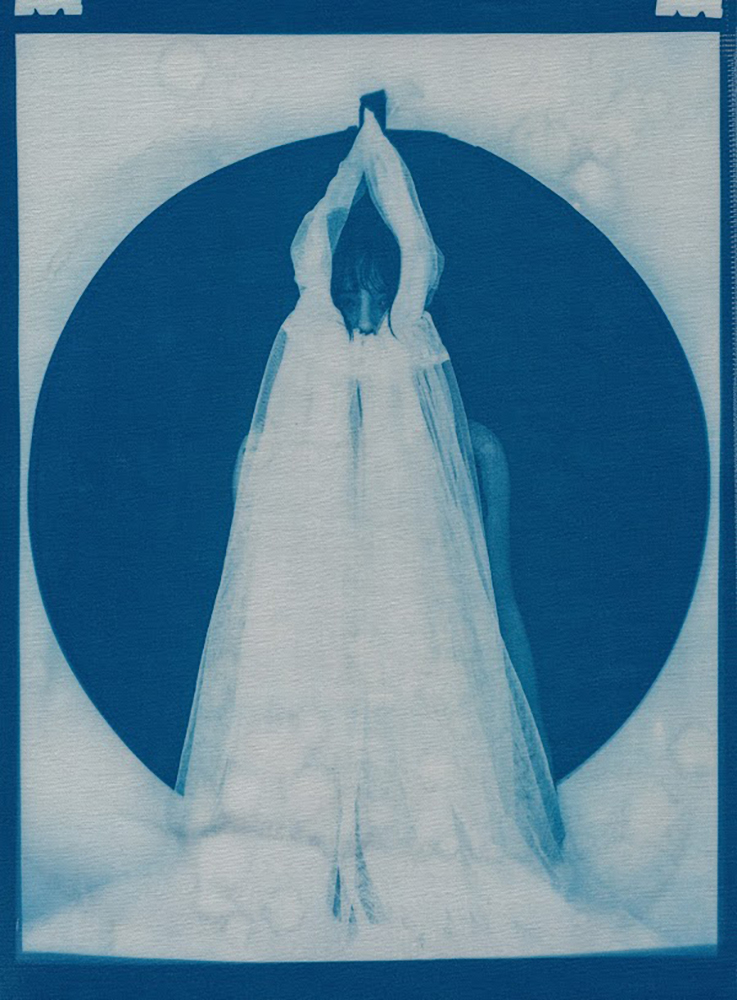

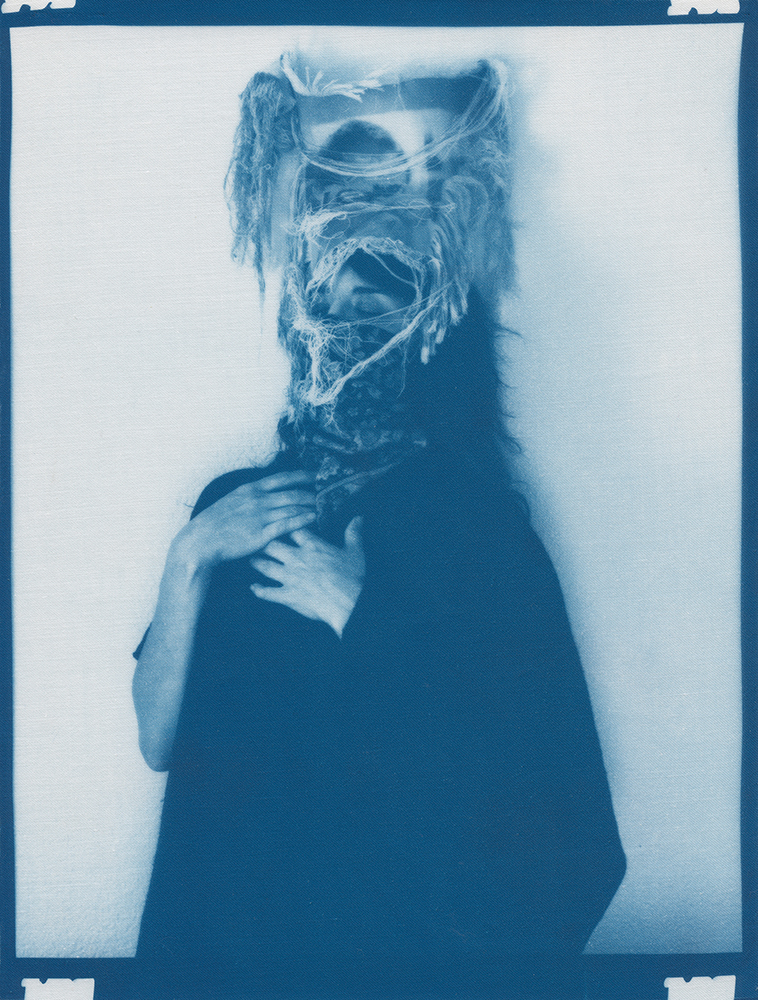

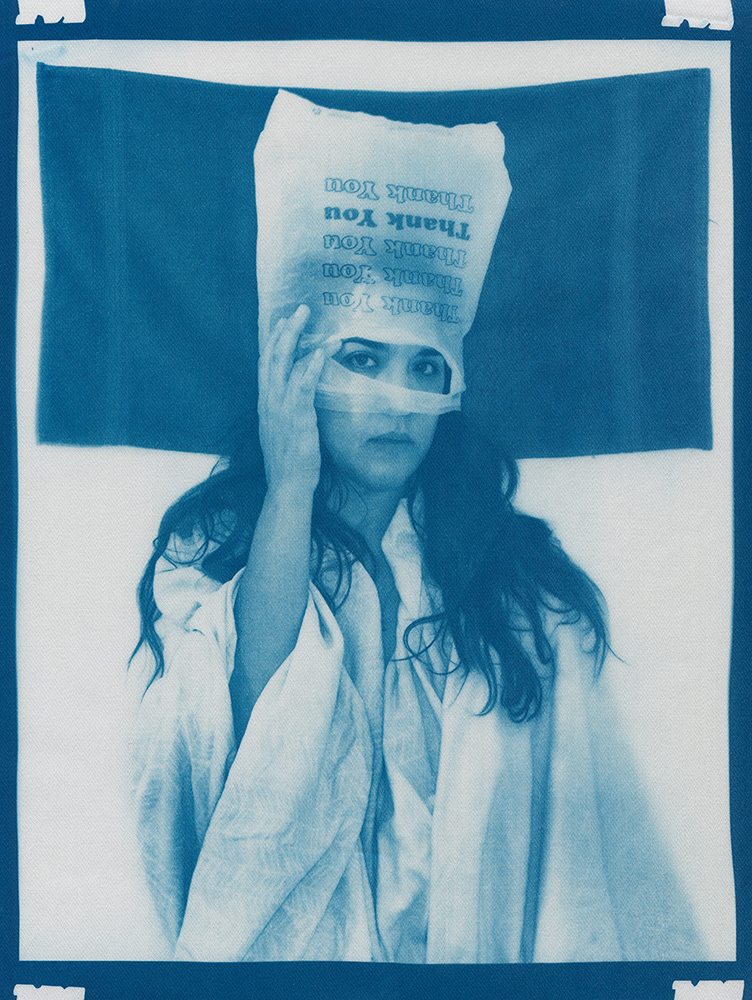

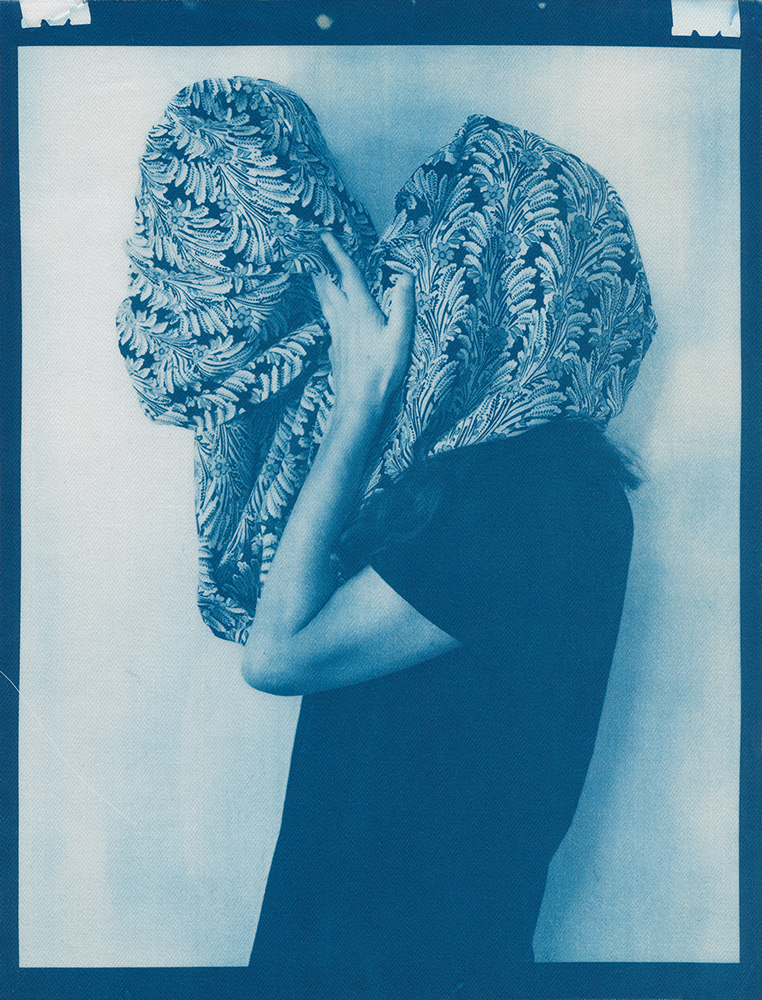

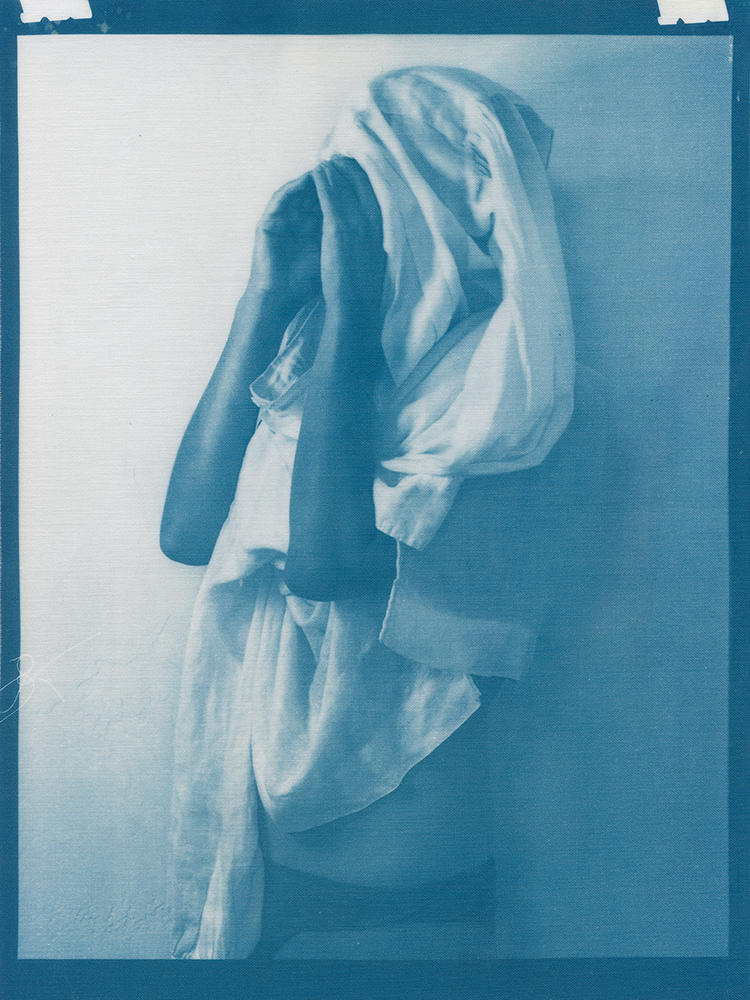

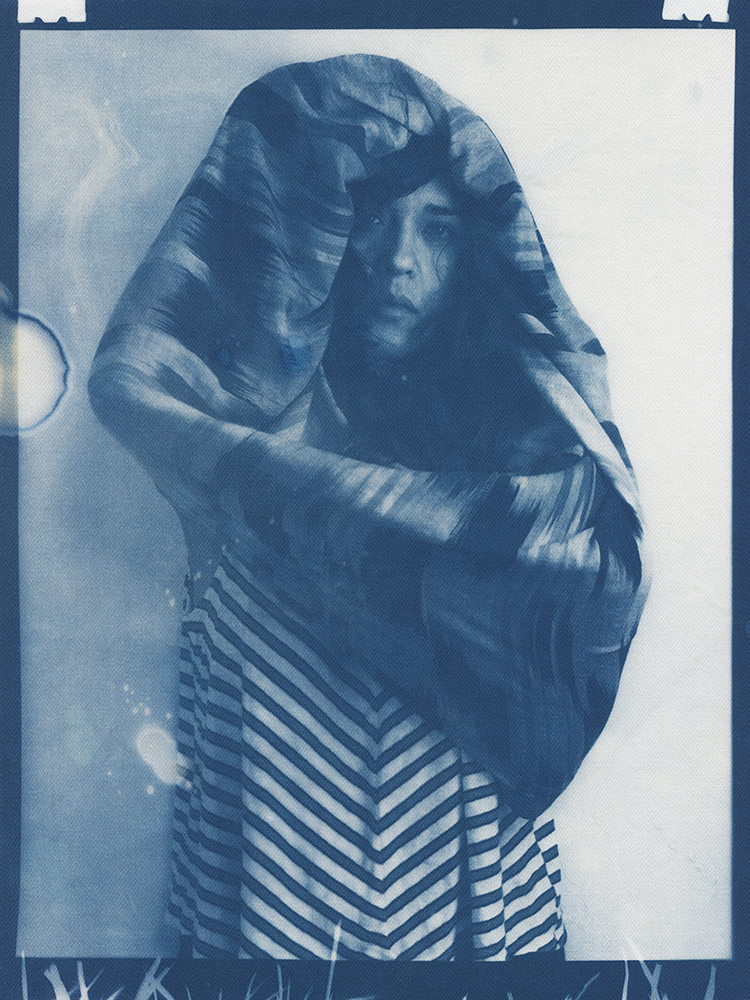

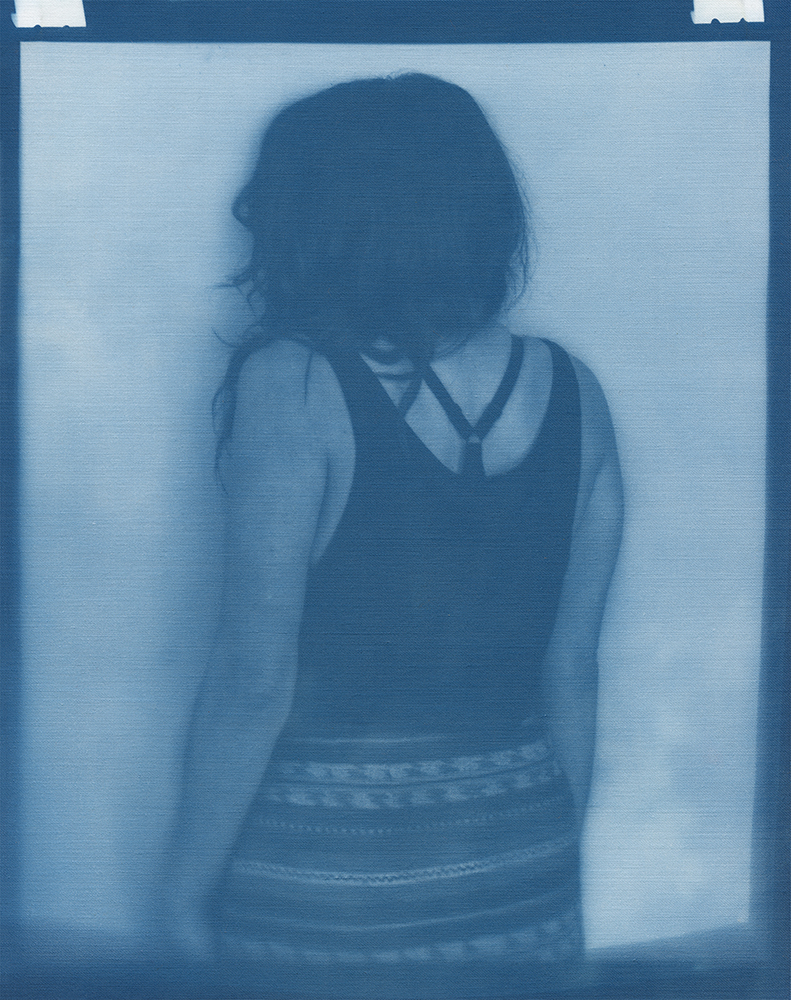

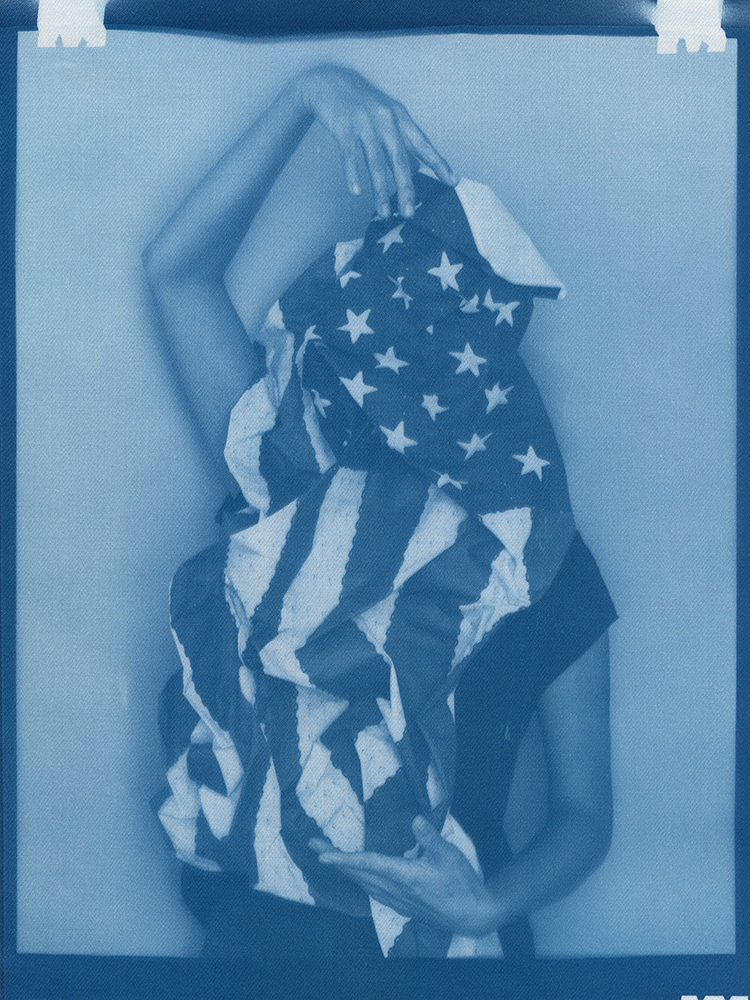

Reading the book is like accessing someone’s private journals from those uniquely frightening and isolating days. The photographs and accompanying text, written by Elkins herself and contributor Joy Sullivan, convey a contiguous cache of information that communicate the most unpredictable and lonely time of the pandemic. And yet, rather than banal and ordinary pictures made at home, we’re shown a fascinating record of the unraveling and rebuilding of a person confined to their private space and sensibilities. Household items, the 19th century cyanotype process and aesthetic, and cultural symbols become fodder and commentary on what it meant to seek protection from the virus in the uncertain time of “flattening the curve” prior to the availability of biomedical measures.

Today Sara J. Winston and Amy Elkins discuss the making of Anxious Pleasures, which will launch at the New York Art Book Fair (NYABF) on Sunday, October 16 at 2pm at +KGP Booth (F23) where the artist will be signing copies of her book.

Anxious Pleasures

“In the spring of 2020, panic surrounding COVID-19 erupted and mandatory shelter in place orders went into effect, forcing me to abandon long-planned portrait shoots, travel, and work in progress in my art studio. I found myself in a 340 sq ft apartment in a Bay-area neighborhood that was emptying by the day. The buzzing silence was profound. Two weeks into isolation, my drive to connect with others and make portraits only amplified. With no safe way to do so, I spontaneously turned the camera on myself to create a portrait. I printed it as a cyanotype, a simple nineteenth century photographic process that was only feasible due to the basic materials I happened to have on hand—a budget printer, transparency film and a package of fraying sheets of cotton pretreated with cyanotype chemicals. At first, I exposed the prints in the unpredictable spring sunlight coming through my third floor apartment window. As the seasons changed, I went on to make them in a garden, on the top of a car, or a patch of wobbly concrete tiles. I rinsed them in water and varying shades of blue emerged. I created a daily self-portrait using this technique for more than a year.

I made most of these self-portraits inside various studio apartments that I lived in alone. To make the earliest pictures in the series, I had to move a couch every day to create space against a white wall near a window. I took others in fleeting spaces while traveling—in a guest room, in a medical examination room, during a pause in the wilderness, and later against the wall of an old California bungalow sandwiched between the mountains and the sea. In the beginning, I often tried to cover as much of my body and face as possible as a commentary on my fear of the virus and my efforts to guard against it. My armor and props ranged from common household items—potholders, tinfoil, dish towels, bedsheets, and toilet paper— to more telling evidence of the unusual consumption that resulted from being stuck indoors indefinitely— Amazon packaging, takeout bags and trash leftover from groceries purchased while wearing rubber gloves and sterilized in whatever way was possible and later consumed. These items shifted as the duration of the pandemic blurred into an unknown stretch of time. The portraits became less about those initial fears and more about confronting the boredom, anxiety, grief, and fatigue of living in indefinite isolation during a global pandemic.

In total, I made these portraits for 377 consecutive days. I made the first portrait on March 30th, 2020, a day when my head was raging in pain, my throat was constricted, and the fear that I might have contracted COVID hung over me before testing was easily accessible. I made the last portrait on April 10th, 2021, the day I received my 2nd vaccination. The days, weeks, and months in between feel like a fever dream—frayed and flickering in multitudes of blue.”

Sara J. Winston: Congratulations on your book, Anxious Pleasures! It is an incredible tome and pandemic time capsule. Thank you for taking some time today to answer a few questions about the process and experience of making it.

Amy Elkins: Thank you. It’s my pleasure. And I love that this coincides with the NYABF where my book launches Oct 16th.

Sara: You state very specifically in your artist statement when you began making self-portraits, March 30, 2020, and when you stopped making self portraits, April 10, 2021, a total of 377 days. At what stage in the project did you know that this work would become a book?

Amy: To be honest, I never thought that far ahead with this particular project. I made the work one day at a time to get through the hardest parts of the Pandemic, when lockdown was the most suppressive and all of us were reassessing how and where we were spending our time. I ended it the day I received my second vaccine, because at the time we all thought these vaccines would mean the end of Covid. Shortly after my last portrait was posted and the end of the project was announced, Kris Graves Projects approached me to make a book… and here we are.

Sara: How did you decide on the book objects scale: 5.13 x 6.5 inches, vertical, hardcover?

Amy: The designer (Caleb Cain Marcus at luminosity lab) spent time with every step. I believe logistically to give space to each of the 377 images, the book needed the scaffolding of a hardcover to keep it together. We wanted it to feel intimate, yet overwhelming and the small but brick-like scale brings these concepts together in a lovely way.

Sara: At what point in the process did you title the work Anxious Pleasures? Is the title a play on the phrase “guilty pleasures,” or a reference to something else?

Amy: It honestly feels a bit blurry to think back to the title coming to be but it stems from what this project meant to me while making it. The days were very uncertain. We all kept pivoting and shifting in so many ways: isolating, curfews, shortages, travel bans, closures, remote work, remote learning, being afraid of the breath of strangers or the proximity of others… the world stood still yet buzzed with collective anxiety. This project gave me a glimmer of pleasure in the thick of all of that. A salve of sorts. My daily anxious pleasure was the making of this work: finding the right props out of what I was stuck indoors with, sorting what to do with them, shooting a self portrait, editing and printing it as a digital negative and then, of course, as a physical cyanotype. Each part of the process took time and consideration and distracted me from the world seemingly collapsing outside.

Sara: What role, if any, did social media play in the process of making this work?

Amy: Since we were all forced into isolation, social media platforms became a form of community for many. I posted my cyanotypes each day I made them with a small amount of text, including what day of making I was in. This felt sort of like a daily check in with the world to announce that I was still alive and creating despite our separation. I started noticing my following was growing and the work was resonating with people from all over the world. That dialogue, of sharing and receiving Covid/isolation/creative experiences pushed me to keep going. The “live audience” felt like it held me accountable.

Sara: Would you share a little about the collaboration with Joy Sullivan on the text? Was Joy brought on after you finished photographing or was the poetry made at the same time as your cyanotypes?

Amy: Similar to how strangers found my work on IG to resonate with their experiences during Covid, I stumbled across the work of Joy through mutual friends and fell in love with the way she used words in such a palpable, and at times, heartbreaking way. When the idea of a book came to be, I knew I wanted some text to accompany my images and Joy was the first person I thought to ask. She wrote the four part poem in the book as a reaction to my photographs. I absolutely love what she came up with.

Sara: The portraits are an interesting taxonomy of who you were and who you were becoming during the fever dream of pandemic isolation. I’m curious if you took more than one portrait each day. Are there any outtakes?

Amy: I did take a handful of portraits with each costume/prop set up each day and selected my favorite to work from. There are many outtakes buried in the mix. Perhaps one day I’ll unearth some of them.

Sara: Does this work in the book form surprise you? Do you find that you ended where you intended, or someplace different?

Amy: I think the book is a beautiful object. Kris and Caleb did such wonderful work from start to finish. And I do think the work is a powerful archive of my experiences throughout the first year of lockdown. What startles me in some ways is how physical, permanent and intimate this book feels compared to the ephemeral blur of isolation they were made in. During the midst of Covid isolation I was creating and sharing these portraits as an act of staying busy and feeling purpose… a way to carry me through from day to day. The portraits and social media posts surrounding them were for the most part raw and uncensored, ranging from playful and absurd to sorrowful and dark. They lacked a self-consciousness. Now that we are… or are pretending to be.. on the other side of Covid I feel far more vulnerability in sharing the 377 portraits in book form that got me through the early days. That and I feel a huge sense of pride in being able to make work daily during such a challenging time. Given the very different experiences of sharing in the midst of vs sharing after, I feel we landed in a beautiful way with this book.

Amy Elkins received her BFA in Photography from the School of Visual Arts in New York City and her MFA in Art Practice at Stanford University. She has been exhibited and published both nationally and internationally, including at The High Museum of Art in Atlanta, GA; Kunsthalle Wien in Vienna, Austria; the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, AZ; the Minneapolis Institute of Arts; North Carolina Museum of Art; among others.

Her first book Black is the Day, Black is the Night won the 2017 Lucie Independent Book Award. It was shortlisted for the 2017 Mack First Book Award and the 2016 Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation Photobook Prize as well as listed as one of the Best Photobooks of 2016 by TIME, Humble Arts Foundation, Photobook Store Magazine and Photo-Eye among others.

Kris Graves Projets (+KGP) collaborates with artists to create limited edition publications and archival prints, focusing on contemporary photography and works on paper that address issues of race, identity, equity, gender, sexuality, and class.

Sara J. Winston is an artist and contributor to Lenscratch.

Follow Amy Elkins, +KGP, and Sara J. Winston on Instagram:

@thisisamyelkins @kgpnyc @sarajwinston

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Luther Price: New Utopia and Light Fracture Presented by VSW PressApril 7th, 2024

-

From Here to the Horizon: Photographs in Honor of Barry LopezApril 3rd, 2024

-

Shinichiro Nagasawa: The Bonin IslandersApril 2nd, 2024

-

Kristine Nyborg: Learning to Speak BearApril 1st, 2024