Interview with Morganna Magee: Reverence for the Land, Animals, and People

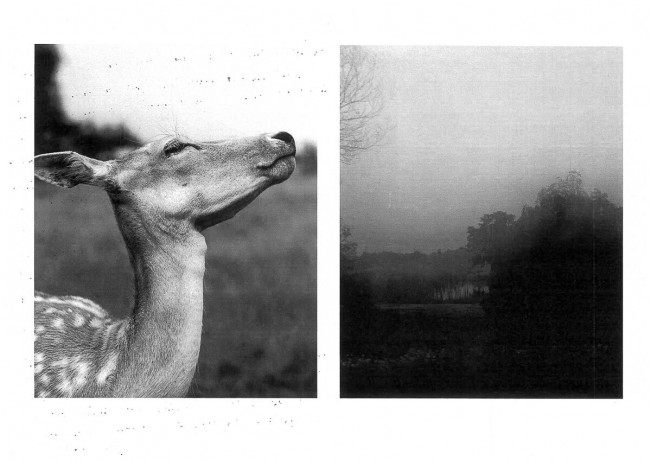

“I acknowledge my position as a settler on stolen Bunurong land in my daily life and art practice. This land has been a place of art making, ceremony, learning, design, politics, wisdom and care for 85,000 years before my existence and will continue to be long after I am gone. I believe I have a duty to show love and care to the country on which I am situated and use my position as a photographer to pay it reverence. The process I use to make photos is slow and deliberate. All images made of the more than human world are done with respect and care. I do not trod on areas where no paths have been made and all animals are free to come and go willingly from the frame of my camera. I never photograph with a long lens, the animals in the photos I make have chosen to allow me to be close and I endeavour to listen to animals however they wish to tell me if they do not want to be photographed. I will never photograph an animal in distress. Images of animals deceased are made to honour their lives and allow me to reconcile my own grief for their deaths. “

– Morganna Magee, Ethical Statement

Off the bat, I was curious about your approach to making work from a historical and mythos perspective. What’s your process like for photographing? Do you work from research in terms of letting it shape and inform how you make images, or is it a separate part of your practice?

It’s really interesting Jake… so I’ve been a photographer for about 22 years, I worked as a photojournalist for a long time, and then I moved into this documentary portrait kind of practice. Which is more of what I was known for for a long time, and is very research-heavy.

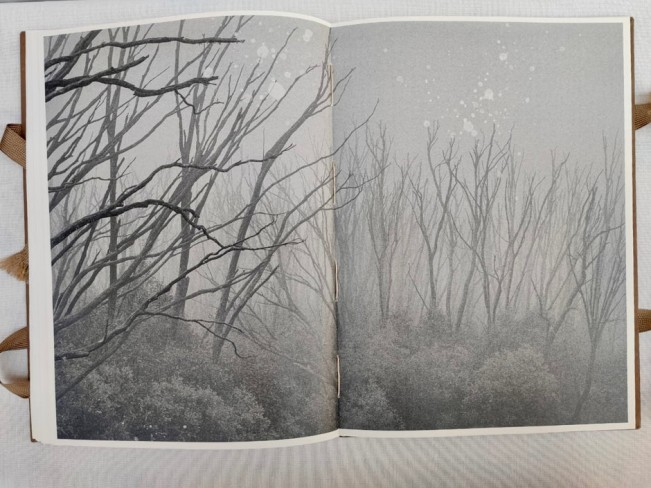

But, the work that I do now, the work that’s become the books, I’ve been really interested in the idea of research as a kind of holistic way of learning. So, the research that I do right now is actually through observation, through being in places.

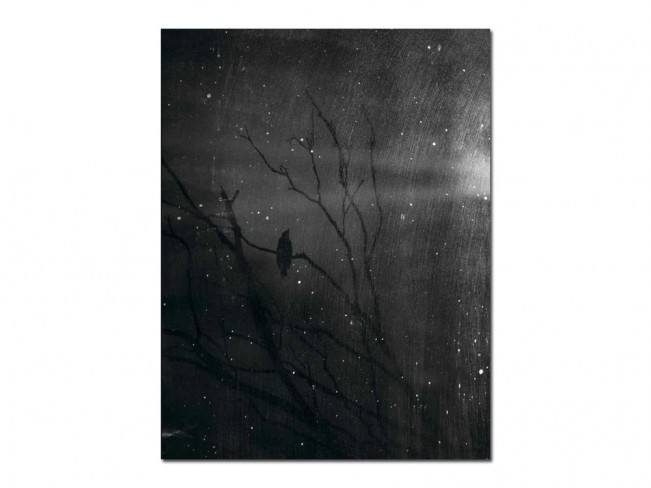

The place that I’ve been photographing, the one I was photographing this morning, I go there literally every single day. It’s 500 hectares, it’s a huge state park, it’s a site of significance to the original owners of the land. And I feel like my research now comes from just being there in the quiet, looking, and trying to understand what I’m seeing.

Then the funny flip side is that I’m also doing a PhD, which is super research-heavy. So, I still feel like I get that kind of academic itch scratched I suppose. But now on a day-to-day basis, it’s really intuitive, which is lovely.

Also, thinking about your approach, and the respect given to the land and animals in your work, do you consider spirituality or animism as a theme you’re exploring? I feel like it’s definitely there, but I was curious to know if there is a concrete connection in terms of it being more of a focal point.

I’m actually pretty misanthropic, to be honest with you Jake *laughs*

And it’s only getting worse as the world gets worse, and as I get older. But I think as a person, I find I’ve always had a very easy relationship with animals in a way I don’t have with people. And that’s not that I can’t speak to people, or that I’m not energetic… but my natural state is actually pretty introverted. So I find being around animals to be incredibly calming for me, I never feel scared around an animal… I feel like I can predict their behavior in a way that I can’t really predict humans. So I have a very biocentric view of the world, which is that all life is equal, I don’t see any hierarchy in the animal kingdom, nor the human/animal kingdom. I think we’re all sort of on par with each other, and that really influences the way that I photograph.

I look at animals through the beautiful tradition of them as symbolism in photography, but I see them as individuals as well. So when I’m photographing a kangaroo, a horse, or a cat, I feel like I’m making a portrait of them in the same way I used to make portraits of people.

Kind of on that point, and especially considering some of your early work, this idea of respect towards the subject, whether it be land, animal, or the person, has always been this thread or tether between everything.

I was wondering if that was ever at the forefront of choosing a subject matter. Is it something that you actively think about and let guide you, or perhaps is it just natural and subconscious?

Well, I’ve gotta say, Jake, that’s one of the kindest things anyone’s ever said about my work *laughs* especially about my older work. Which I sometimes feel a bit uneasy about, the work about strippers specifically I made when I was 18. I think photography and privilege come really intertwined and there’s a very interesting dialogue about it.

I feel like in the States it’s very explicit, where as in Australia, it’s starting to come out. We’ve got some pretty amazing scholars and artists working here to talk about the role that photography has with imperialism and the disrespect that’s been shown through photography in this country, and all countries. So I definitely feel that if anything, human, or more than human, is giving me grace and allowing me to photograph them, respect is the minimum I can show.

Weirdly, my first job when I graduated with my diploma, was for a tabloid newspaper, which was the total opposite of that. It was like, you’ve gotta do paparazzi work, I was so bad at it Jake, I was incredibly bad… like I don’t know why they hired me *laughs* cause I was just like, nah I’m not doing it!

I think having respect, but also for me… reverence, for what I‘m photographing is really important, and I think those two things are quite intertwined. I think if you really revere and admire something, you have to show it respect.

Building off that, would you mind talking a little bit about your PhD work with kangaroos?

Yeah! So I’m about halfway through the PhD now and I’m looking at a couple of different things.

I’m looking at why this animal, which is a national symbol and literally an emblem, is quite intensely disrespected. It’s disrespected in online culture, in meme culture, but it’s also disrespected here. Kangaroos are hunted essentially for dog and cat food. It’s this weird thing where this animal is so symbolic of this place where I live, but then also settler culture is so abusive towards it.

And I know that happens in a lot of places. Like there was a pretty horrible case in the States actually, I think in Montana, of someone trapping and killing a grey wolf which was filmed, distributed, and monstrously horrific.

But my thinking is that, with that really lovely thing you said about respect, I think that if you can respect something that you’re photographing, you’re forced to understand it, you’re forced to slow down, and you’re forced to think. The premise of the PhD is essentially that we can use photography to decolonize the representation of kangaroos, and the way that I’m trying to do that is by trying to understand them as individuals.

So like, I don’t know if you have any pets or animals in your life, but, my cat is my cat, my dog is my dog, and we see these individual personalities and traits in them. But that is with domestic animals, and definitely in Australia, again with settler culture, we don’t attribute that to native animals, they’re seen as pests, something in the periphery.

So, I’m interested in trying to work out how to photograph animals in a way where they almost explicitly give me their consent. Actually, after I speak with you today, I’m heading out to see a kangaroo rescuer to talk about the body language of kangaroos and how they respond to each other when humans aren’t around, versus when humans are around. They’re very social animals, they live in what’s called mobs. They have these big family friendship groups, it’s a matriarchically society and they even have “cool girls” within their social groups *laughs* they have like a queen bee, which I think is just the cutest thing ever!

The other girls will follow her around and the boys will try to suck up to her, and so they’re these incredibly complex social animals, despite that again kind of meme culture idea of them being these big strong angry alpha males. So, I’ve been using AI a bit to sort of work through archival images and rework them in ways that play on the idea of what we think animal value is… but, what I’m hoping to be able to do, because a lot my process is 8×10 large format, is to be able to get to the stage where I can make a portrait of a wild kangaroo with that camera. But to know that it is comfortable, it’s not scared of me, I’m not scared of it, and it’s really allowing me to photograph it.

I think as photographers and practitioners in 2024, and as humans in 2024, we need to be thinking about these things. We need to be thinking about the consequences of our actions, no matter how big or small, and it’s very important to me, especially with animals, that they’re not scared when I’m photographing them. I don’t want to participate in anything that is scary or makes anyone or anything uncomfortable.

On the topic of that body of work, do you see it becoming a book? Or how do you think the work will culminate outside of the PhD and research side of things?

It’s interesting because with the PhD it’s really about testing ideas.

At the moment, I’m looking at using some virtual reality for the final outcome. I love the idea that you in Maine might be able to experience this as well. That being said, I’m still the practitioner I am, and I’ve got three and half years to do the PhD, but afterward, I would love to do a book.

If I know that a kangaroo could be comfortable being photographed the way that I want to photograph them, I would loooove to do a book. I would absolutely would love to do a book about them.

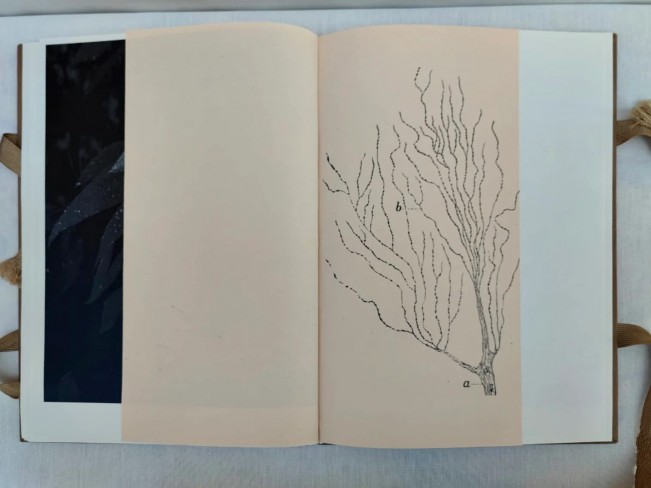

If it does become a book, do you think text alongside images would be more integral, like if it were to be this more research-heavy project? I’m curious about that, especially thinking about Phenomena. In the book, there are diagrams included, and there appears to be a more scientific approach to making a photobook… it doesn’t even really look like a photobook from the outside, it looks more like a journal.

So, with that in mind, I’d be interested in seeing how a project with so much research behind it could unfold, and what form it’d take.

Yeah! I think it’s an interesting thing with text in books as well. I feel like with a photobook, and the reason I like them so much, is because it’s a way for someone to experience your work away from you. I find exhibitions really awkward… because I’m awkward *laughs*

It’s like, “I put everything up on the walls, say something nice about it.”

I always feel a little uncomfortable. Like now there’s a giant print behind me from a recent show I was in, I just end up with all these things around my house. I tried hanging this big one and it went through the wall, like the nail went through the wall and ruined the bathroom… so I think that kind of just sums up everything *laughs*

But, I think text in books can be very interesting. It has to be done well though, and I work at a design school so I have so much respect for designers. I think that with the photobooks that I’ve done, the ones with Tall Poppy, and also with Phenomoena, it’s been so great to work with other people who can have ideas, and I’m super open to collaboration.

There’s a book here, Oreille Coupée, by Julien Coquentin, have you seen it? It’s about the wolves in France. The photos in there are quite stunning, and they use text quite well as sort of chapters. He’s got these incredible landscapes, but then what I looove, is that he used a trail camera and made images at night, that he then turned into cyanotypes.

It’s about this village where wolves had disappeared, and then they suddenly started coming back. What I love about this book, is that he had made all these trail camera images, and he couldn’t quite get “the” photo of a wolf, and then, he was trying to make them cyanotypes. Something went a bit whacky with the chemicals, which is why they have that green and yellowy/bluey cast to them. But then he realized afterward, with his research, that it mirrors how wolves see, which I thought was incredible!

So I love the idea that as he was making this book, he discovered more things through the book-making process, that’s something for me that I love about book-making. You make this work but then it becomes this whole other thing, it’s so exciting!

But I feel like with text, it can work really beautifully, it just has to be considered.

I guess, with thinking about putting the kangaroo work into a book… after the PhD is finished, I could write something poetic, or even bring in a writer who could speak about the majesty, which I could intertwine with some of the facts as well. But yeah, we’ll see!

Also, thinking about how you’ve worked with a couple of different publishers, has there been a difference between how much creative control you’ve had over your multiple projects?

So, Matt Dunne runs Tall Poppy Press, and now I’m in it as well, but he approached me in 2020 when we were in lockdown, wanting to turn Extraordinary Experiences into a book. At that stage, he had only done one book, and when he contacted me, I just kind of thought, “What do I have to lose? Why not?”

I know that I really liked the work, but I didn’t really know where to put it, certainly, no one was having shows in 2020, so I was like, “Yeah, let’s go for it!”

What was really interesting about working with Matt, who’s become a good friend, is that he’s very earnest, very enthusiastic, and very open! We couldn’t physically meet for a little while, so we were just sort of trading ideas back and forth about what the book would look like. But he was really receptive to the idea of Extraordinary Experiences feeling a little bit scrapy.

The work is quite complex, and I like the idea of what its held in being a little unassuming, so we went back and forth and he sent me the first draft. I felt he was being very polite with the work. So, I said, “Let’s play with it,” and we ended up really codesigning the book. It was kind of incredible, from ideation to being ready, even with lockdown constraints, it was probably like 6 weeks. It was just this really natural flow, and I remember when it was going to press I said to him, “Should I be worried? Should it have been this easy and gone so simply?”

I guess I was just worried we may have rushed it… but I wouldn’t change anything about that book, to be honest, I really love the way it came together. With the second book we made though, I had a clearer idea of exactly how I wanted it to look, and Matt wanted to play with a few design things, so it was very hands-on.

Whereas, Phenomena, was a really different experience that I could have only had after doing the first two books. They helped me understand exactly what I liked and didn’t like. So, when Origini contacted me they said, “We like your work and we want to do a book with you.”

I love what they do, and have for a long time, so I said, “Of course!” I don’t know who would say no to that, but definitely not me *laughs*

I said, “I’ve got all of this work, because I make work every day, and I’m going to send it to you and you can do whatever you want with it.”

I think that they initially, and I haven’t spoken to them about it, but maybe they weren’t expecting me to be so hands-off, but I just really trusted them! I had never met them, we don’t speak the same mother tongue, but I was like, “I love what you do!” So, we worked on the sequence, which was really of back and forth, a couple of WhatsApp messages, things like that. Then, I get this parcel from Italy with the dummy of the book, and this was the moment that I cried. I could not believe it. I felt like these people had seen into my soul or something. Everything about it, the use of the peach, the paper stock, the drawings, as you said, the little bit of text in there, the gold thread going through, everything… I just could not believe that these people, whom I’ve never met, on the other side of the world, get me!

I don’t know if I will ever have that experience in my career again, and it’s interesting because a lot of the time people focus on the darkness of my work, because it’s literally dark, and sometimes people think there’s this element of spookiness or creepiness. I feel like Origini just saw it as a celebration and saw the magic in it. I am so grateful for everything that they’ve done!

Even just the print quality… it’s so yummy!

It’s so yummy!! Sooooo yummy! *laughs*

I was just showing it to one of my best friends for the first time the other week, and I feel like it’s not even about my images. It’s so lovely that my images are in it, but just as an object, and the way it’s printed… it’s just so beautiful… and they’re all handmade! 250 copies, and she did everything… all of that incredible work, you know with the spine, the little bow binding… she did that, handmade! And she even made the unicorn stamp, which is insane, because I have a unicorn tramp stamp tattooed on the back of my spine *laughs*

Speaking about book-making, has becoming a book artist reshaped your process of image-making? As in, has your practice as a photographer evolved around making images with books in mind?

I don’t know that I’ll ever move away from books. It’s not necessarily on my mind while I’m out photographing, but I’m very active on Instagram, which is sort of like a journal for me to remember where I was and what I did. But even sometimes I use Instagram for posting diptychs and triptychs, and that’s book-making.

So, I think now, even when I look at standalone images on my screen or when I develop film, I can see what “that” will sit next to. I’m definitely thinking in books a lot more than I realize because it’s been 3 books in 18 months, which is… a little silly, but also fantastic and has been really wonderful!

I’ve got another book in me at the moment but I’m just working out if I should hold back a little. I was thinking about doing a small edition of like 10 handmade books, I don’t know that I’ve got the skills to do it though, I’m a little bit of a hot mess *laughs* so we’ll see how that plays out.

It’s interesting though, a friend of mine who’s done some really beautiful books talks about how she’ll edit a book, find holes, and then go and photograph to fill those holes. I don’t work like that at all, I go off what images work together, and what images feel like they unfold nicely together, and I’ll sit with a sequence for a little while.

But I think as I’m making this work, because like I said, it’s all photographed in the same place, and it’s all in that similar mindset about the eternal nature of the world, and how finite humans are, and what will be here after we’re gone. I think putting it into book form just comes really naturally after making the photographs.

Thinking about how your work has progressed as an artist, it feels like ideas of family, home, place, the land, and grief, have been pretty consistent throughout. Have you always approached making work as a way of healing or processing emotions? Or was there a sort of light-switch moment?

100% a light-switch moment!

I discovered photography as a teenager like a lot of people did, and it was my way of understanding how to be in the world and how to get myself out of my own head. I was a pretty shitty little teenager *laughs* but photography gave me something to hyper-focus on, so that was really great.

So, with a lot of the early work, it was a way to look at the outside world, but then when I undertook my master’s, I started making work specifically about my mother, and my relationship with her.

Then, that kind of snowballed, so in 2019… I’m quite a spiritual person, I think about rituals, and I think about traditions and cycles… 2019 was my bad year. I think every 7 years I have one, but that was the worst that I’ve ever had, and I essentially had a mental breakdown.

I was dealing with a lot of unprocessed things, one of the biggest ones being grief. My father died when I was in my 20s, and my brother and I were carers for him for a long time. So the experience of my home life as a child, and everyone’s experience is their own, but mine wasn’t necessarily happy. My dad was an alcoholic, so there’s all these things around that, and then when he died, I sort of just pushed away all those feelings and got on with being in my 20s, doing everything that comes with that.

Then, when I started making this master’s work about my mother, I realized I needed to include my brother, who I hadn’t spoken to since my father died. So it was a lot… like a lot… a lot to put on myself for a master’s and probably wasn’t healthy. Then, subsequently to that, all this other shit went down in my life, and photographing became my way to process it.

I didn’t realize it when I was doing it, that body of work is called, All the Things Unsaid, it looks different from what I do now, it was all color large format, but it was the start of me slowing down a little bit with the way I photograph, and really considering it. I made that into a book… a terrible book, it’s bloated and awful *laughs* but it was fine for what it was, but will never really see the light of day.

That was the start of it though, and after the mental breakdown, we entered lockdown. So it was this really weird thing, starting 2020 not knowing what my future was, and being so depressed and not wanting to leave the house… and then we went into lockdown, and I literally couldn’t leave. We had a pretty extreme lockdown here.

But for me, it gave me the space to process the grief and depression I was feeling in a way that was almost like… luxurious? I feel terrible saying that because the pandemic was this whole other than what our lockdown was, it was awful and terribly destructive… but it forced me to really sit in my feelings because there were no distractions.

Now, I’m not depressed anymore, but that growth and experience have certainly carried through my work. That process of being able to be in the world with a camera and be in a meditative, hypnotized state, is completely integral to the way I work. It’s interesting with my family too, because photography completely became a way to heal. You’re quite literally shielded with a camera, especially an 8×10… what a stupid way to photograph your family you haven’t spoken to in 10 years *laughs*

But I think it gave my brother a chance to atone as well, since he had to really obey me, and I’m the baby sister so I liked that. He really had to sit there and listen, and he let me photograph his children, my niece and nephew, who I still photograph. Which I think is also a little bit of an atonement as well.

It’s an interesting shift in my work, and it’s probably the reason I don’t work commercially anymore, because after that, I started thinking about what photography is to me, how important to me, how it’s a real lifeline for me, and I didn’t want to muddy that with capitalism *laughs*

Morganna Magee is based in Melbourne, Australia, living and working on the unceded land of the Bunurong/Boonwurrung people of the Kulin Nations, the foothills of the Dandenong ranges. Her practice explores human relations to the more-than-human world using traditional photographic practices in non-traditional ways.

In 2022 she published her debut monograph “Extraordinary Experiences” with Tall Poppy Press. The book was nominated for Australian Photobook of the Year, and was listed as one of the photobooks of 2020 by both Gabriela Cendoya and Robin Titchner. Enjoying the process of bookmaking so much, Morganna joined Tall Poppy Press with Matt Dunne and has since published “Beware of People Who Dislike Cats” in 2023. In addition, “Phenomena” a collaboration with Italian publishing house Origini Edizioni was launched at Polycopies, 2023.

Her work has been awarded and exhibited both nationally and internationally recognised by institutions such as The British Journal of Photography, The National Portrait gallery Australia and Miami Art week. She is regularly commissioned for editorial and large-scale community arts projects.Her images have appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Guardian, The Age, Art and Australia magazine amongst others

Morganna is the Major Discipline Co-ordinator for Photo Media, at Swinburne University of Technology and is currently undertaking her Ph.D ‘Not Tame Enough‘ which questions how colonial photographic practices have misrepresented the Kangaroo.

Follow Morganna:

Jake Benzinger (he/him) is a photographer, book artist, and writer based in Rockland, Maine; he received his BFA in photography from Lesley University, College of Art and Design in Cambridge, MA. Through the dislocation of space, he weaves together imagery to construct a world that exists in the liminal, investigating themes of mysticism, identity, ritual, and animism.

His work has recently been featured by Float Magazine, Transference Magazine, and Fraction Magazine, and has been exhibited both nationally and internationally. Jake’s body of work, Like Dust Settling in a Dim-Lit Room (Or Starless Forest), was self-published, shortlisted for the 2023 Lucie Photo Book Prize, and sold out of its first edition of hardcover books. A second edition was released in late 2023, coinciding with a solo show at the Griffin Museum of Photography.

Jake is currently a gallery assistant, a content editor for Lenscratch, and the founder of wych elm press.

Follow Jake:

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

In Conversation with Louis Jay: Marrakech Face to FaceFebruary 15th, 2026

-

Shane Hallinan: The 2025 Salon Jane Award WinnerFebruary 12th, 2026

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026