Matt Black

For a number of years, a good friend who is a nurse in an agricultural area in California, has shared with me her efforts to help a community of farm workers from an region in the mountains of Mexico called Mixtecapan, where the inhabitants don’t speak Spanish, but their own pre-Colombian languages. They have had a difficult transition into American culture, and little ability to communicate their needs and struggles. I was delighted to learn about Matt Black’s project, The People of Clouds, focusing on this population and am thrilled to be able to help bring exposure to his Kickstarter campaign.

Matt also comes from an agricultural community in California and began taking photographs at an young age. He worked as a newspaper photographer, and went onto to become a photo journalist whose interest is in changing rural economies, migration and cultural change, themes that he has been exploring photographically for over a decade.

Matt’s work has received grants and awards from the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Rockefeller Foundation, the California Arts Council, Pictures of the Year International, the California Council for the Humanities, the Alexia Foundation for World Peace, the Sunday Magazine Editors Association, Communication Arts, American Photography, Lightwork, and the Center for Photographic Projects. His work has also been named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and has received a Golden Eye award from the World Press Photo Foundation.

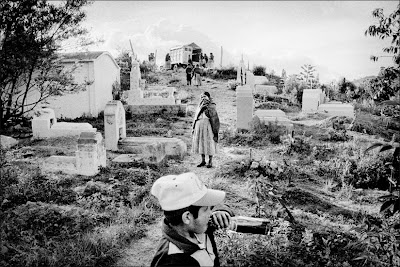

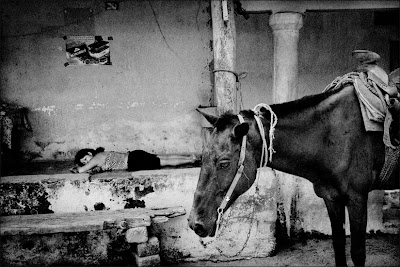

The Mixteca, a rugged mountain range in southern Mexico, is one of the most isolated and impoverished regions in Latin America. Named during the reign of the Aztecs as Mixtecapan — “Place of the Cloud People” — the Mixteca’s isolation and rugged landscape have sheltered its people from the outside world since before the Spanish conquest. Still today, pre-columbian languages like Mixteco, Trique, and Asmuzgos are spoken more widely than Spanish, and cars, electricity and indoor plumbing are recent introductions, if they exist at all.

Named the “Place of the Cloud People” by the Aztecs, the Mixteca is home to one of the oldest and largest indigenous cultures in the Americas. Rugged and remote, the isolated region sheltered a pre-Colombian way of life that largely vanished from the rest of Mexico in the aftermath of the conquest. At its heart, it’s a culture of the land, and corn. Along the region’s hillsides, it is still possible to glimpse ancient terraces, canals, and runoff channels that protected the Mixteca’s rich but fragile soil, and nourished its inhabitants, for thousands of years.

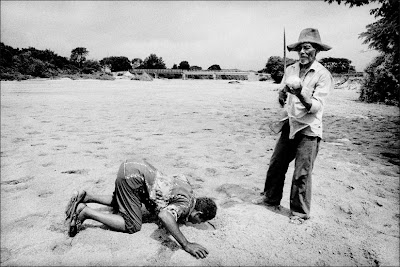

But today, these ancient farming traditions have been lost, replaced by chemical fertilizers, hybrid seeds, and herbicides, the trifecta of modern agriculture heavily promoted in indigenous communities by the Mexican government and international charities as part of the “Green Revolution” of the 1960s. When combined with slash and burn farming, the Mixteca’s steep terrain, and the loss of other indigenous soil-preserving traditions like multi-cropping, these imported industrial agricultural techniques have turned Mixtec corn farming, one of the world’s oldest and most perfectly integrated agricultural systems, into a soil-eating machine.

Today, much of the Mixteca has been declared an “Ecological Disaster Zone,” the result of unchecked erosion, deforestation, and soil exhaustion. Per capita maize consumption is less than ten ounces per day, 90% below US rates, and fewer than a third of children under the age of five show normal growth by weight and height. Ranked on the UN’s Human Development Index (HDI), the Mixteca’s poverty is deeper than nearly all of Latin America’s, comparable only to areas of Africa, India, and the Gaza Strip. Far from sparking a Green Revolution, the industrial farming techniques prescribed to the Mixtecs have resulted in their becoming unable to even keep themselves fed.

Nearly a quarter million Mixtecs have emigrated to the US. Some villages have lost as much as 80% of their population and have become little more than ghost towns. “I only think about dying,” one elderly man told me. “My only worry is how my funeral will be.”

I am seeking your support to help tell this important story. Your pledge to this campaign, a collaboration between Orion Magazine, the nation’s premier environmental journal, and Daylight Multimedia, a leading pioneer of online documentary work, will enable me to create an in-depth chronicle of this modern day, man-made Dust Bowl and document the profound social repercussions left in its wake.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Shinichiro Nagasawa: The Bonin IslandersApril 2nd, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Lorraine Turci: The Resilience of the CrowMarch 16th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Rayito Flores Pelcastre: Chirping of CricketsMarch 14th, 2024

-

The International Women in Photo Association Awards: Louise Amelie: What Does Migration Mean for those who Stay BehindMarch 12th, 2024

-

Brandon Tauszik: Fifteen VaultsMarch 3rd, 2024