Karen Navarro: “Somos Millones” at Foto Relevance

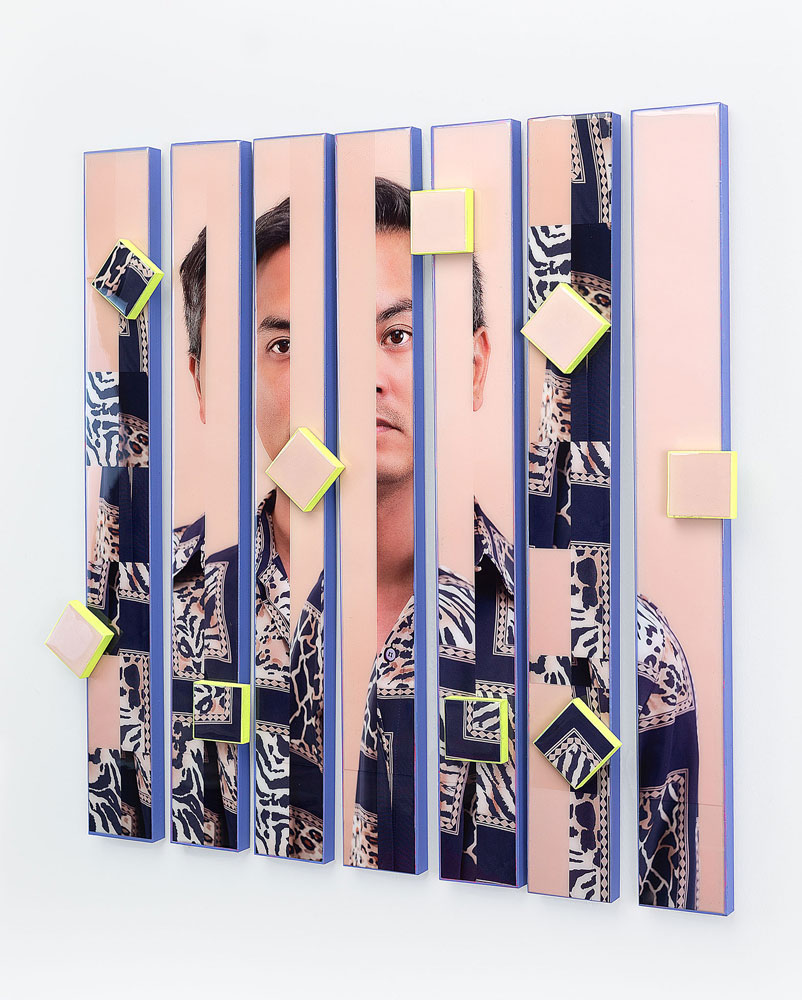

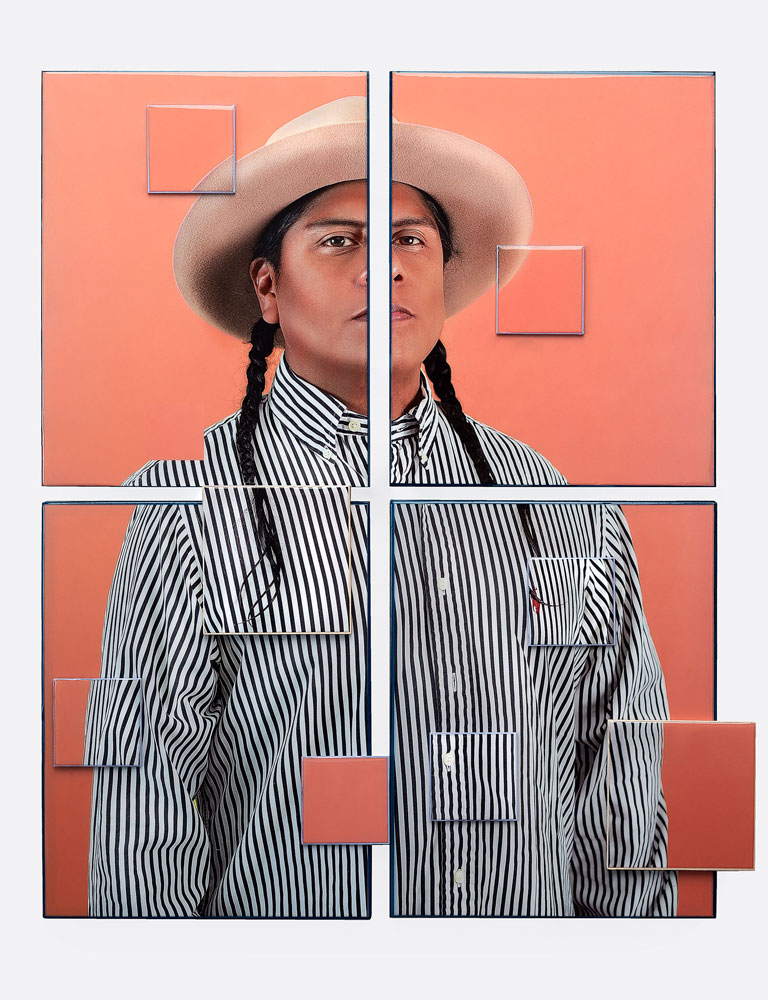

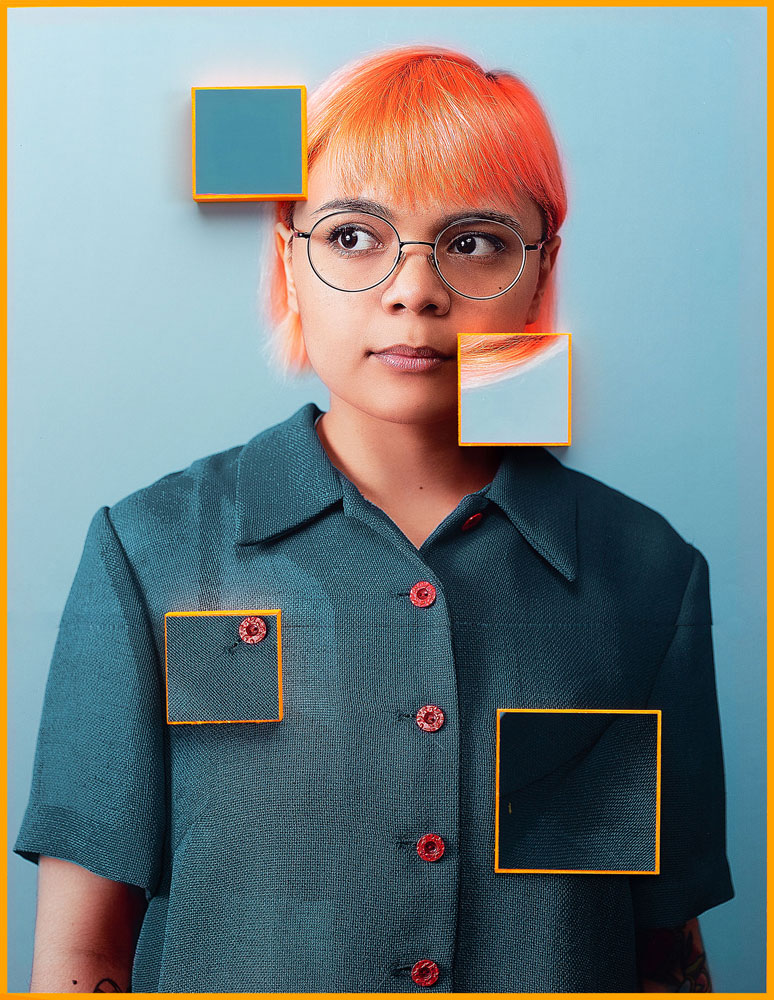

HOUSTON, TX—Karen Navarro‘s multifaceted celebration of immigrant diasporas in the United States in her newest exhibition Somos Millones represents an expansive milestone for the Argentine artist. Accompanying her acclaimed deconstructed portraits with light works, crowd-sourced skin tones, text, demographic data, and participatory installations, Navarro dynamically reassembles fragments of public identity and the aesthetics of dislocation into the playful allure of the abstract. Colorfully echoing the playful modularity of Robert Heinecken’s Multiple Solution Puzzles and Glenn Ligon’s light works, Navarro has created a unique visual language of prime craftsmanship and forward-thinking vision that is irrevocably her own.

After immigrating to the United States, the Argentine artist began to navigate her own mobilized identity by photographing the immigrant communities around her. This co-creative yet deeply introspective act of seeing herself through others presents itself as another question rather than the end of her inner quest: How can we migrants define ourselves outside of the hegemonic norms through which ‘immigrant-ness’ is normatively constructed, entrusted, and performed in the historic consciousness of the United States? The jigsaw-like and topographical quality of the works suggests an answer as mobile and adaptable as the “ambivalent psycho-geography”¹ of the immigrant population that sustains an integral part of the U.S. workforce and post-industrial economy.

Somos Millones—on view at Foto Relevance from January 13 through February 25, 2023—delivers a critical reminder amid a climate of increasingly hostile xenophobic demagoguery: Portraiture as an act of defiance attests to the power that counter visuality plays in reshaping the immigrant experience into a legitimate identity in the global imagination. However, such feat is only possible if we defy every internalized constriction that occludes our capacity for self/representation in the larger cultural and political arena. Much like the hybridity in Navarro’s photo works, it is this “potential for diversity and variability of structures”² that will allow millions to enact such pivotal agency. Only then can we envision a society where the wide spectrum of migrating identities can fully blossom in the shifting tectonics of a more pluralistic American national identity. As art historian and cultural critic T.J.Demos has noted, “far more radical is universalizing the migrant as the experience of being human, and determining a politics of equality on that basis.”³

In this interview for Lenscratch, Karen Navarro speaks to Vicente Cayuela about her inspiration to create work addressing photo-sculpture, race, indigeneity, and her experiences as an immigrant in the United States.

Karen Navarro is an Argentinian-born multidisciplinary artist currently living and working in Houston. Navarro works on a diverse array of mediums that include photography, collage, the use of text and sculpture. Her image-based work and multimedia practice investigate the intersections of identity, representation, race, and belonging in reference to her migrant experience, her Indigenous identity and the history of colonization and its influence. Her constructed portraits are known for pushing the boundaries of traditional photography and the use of color. Navarro has won numerous awards and grants for her mixed-media photography, among them the Artadia Fellowship, the Top Ten Lensculture Critics’ Choice Award, and the HCP Beth Block Honoraria, and has been shortlisted for several more, including the Photo London Emerging Photographer of the Year Award and The Royal Photographic Society, IPE 163. Her work has been exhibited in the US and abroad. Selected shows include Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH), USA; Galerija Upuluh, Zagreb, Croatia; Holocaust Museum Houston, USA; Artpace, San Antonio, USA; Melkweg Expo, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Houston Center for Photography, Houston, USA; and Museo de la Reconquista, Tigre, Argentina. Navarro’s work has been featured in numerous publications, including ARTnews, The Guardian, Observer, Rolling Stone Italia, and Photo Vogue Festival Italia.

Follow Karen Navarro on Instagram: @karennavarroph

Somos Millones at Foto Relevance

Vicente Cayuela: Karen, congratulations on your new exhibition! First of all, I am very interested in learning what the biggest challenge was when you began working in the three-dimensional realm, and the most exciting.

Karen Navarro: Thank you, Vicente! I would say the most challenging is finding the right materials and logistics, and the most exciting is the process. I always have to be open to adapting to the work’s needs rather than what I want to make. It’s a constant tension between me and the work—a dynamic that generates an internal dialogue.

VC: I am glad you bring up this idea of growth and materiality. Most visual artistic practices require a great deal of manual labor—especially sculpture. However, many immigrants lack social mobility and are stuck doing repetitive manual labor. Is that something you think about in your sculptural work?

KN: Indirectly, in a way. I grew up in this kind of environment. My grandmother made and fixed clothing for a living; and my stepfather—who is a refinery worker and who occasionally took on construction and mechanical work to make ends meet—built our house from the ground up with his own hands.

VC: Thank you for this lovely anecdote about your family and for taking us to Latin America for a moment—a place that informs not only your background but also some of the materials you used in this exhibition. Can you tell us more about the obsidian stone in your work Somos Millones?

KN: The obsidian stones take on various meanings and have been vastly used by ancient peoples from the Americas to make weapons, implements, tools, ornaments, and mirrors. I was particularly inspired by its use as a mirror and its meaning. Aztecs believed that by gazing into an obsidian mirror, sorcerers traveled to the world of gods and ancestors. Metaphorically, the mirror catches my reflection and includes me among them. I’m no longer the “other,” I’m part of it all. Somos Millones (we are millions) makes reference to the population number of Indigenous peoples, specifically Mapuche, in Argentina and Chile.

VC: I love that the material allows you to reposition yourself within the rich history and mythology of Latin American culture. Is the act of photographing others also an act of self-reflection, a mirror of sorts?

KN: There is a very meditative process that comes with the labor-intensive work I do. I take this time to reflect upon my identity as well as our collective ones. In making portraits of others, I look to connect. Even though our experiences are vastly different, there is a certain understanding between first, second, and third-generation BIPOC American immigrants and myself, that I can’t get with anyone else. It’s also a form of validation. To me, it is a way of re-framing the history of portraiture and answering the questions “by whom” and “for whom.” I want the subjects to be celebrated, to be part of history.

VC: This idea of “validation” is very interesting to me. Immigrants constantly have to face stereotypes that shape how we see ourselves and also push us to conform to canons of “Americanness” and “immigrant-ness.” On top of that, the media often promotes forms of “sanitized discrimination” by which xenophobia is made more palatable to American audiences. How do you think we can transgress these impositions?

KN: The media and history have long been defining certain identities and it is hard to break free from that—whether internally or externally. The blank spaces in my work not only represent that piece of information that is missing—whether is because we have not written our own stories or because we do not have access to our ancestors’ knowledge. They are also a possibility to fill in the gaps with the story we want to tell. In América Utópica, for example, the idea of the use of neon comes from light/hope. While the work is a demographic representation of the future of the nation, there are some questions regarding the actual space that we are going to occupy and inhabit. I hope the questions to those answers will turn out positively. But only time will tell.

VC: The use of light in this piece reminds me of Glenn Ligon’s neon works America and Double America, which also deal with identity and race. Have you been inspired by Ligon in any way?

KN: Glenn Ligon has been and is a huge influence. His work is powerful, beautiful, and aesthetically simple, but conceptually complex and strong. Although both of our works have the word “America,” in them, mine is “the United States of America.” I’m always very cautious not to use the word “America” to refer to the United States because, for me, America represents the whole continent. On top of the neon, you can see the clear acrylic letters “The U.S. of.” I was also thinking about capitalism and economics. The font I used was inspired by the “United States of America” text found on the one-dollar bill.

Glenn Ligon, Double America 2, 2014, neon and paint, installation view, Broad Museum. Photo: CC BY-NC 2.0 by Robert Corder (November 6, 2017)

VC: Thank you for making that linguistic distinction. Continuing this conversation about your new light works, can you tell us more about the role that analyzing U.S. Census data predictions play in your practice?

KN: My piece Shine America 2043 was created during the confinement and around the time Black Lives Matter protests for George Floyd were happening. It was a breaking point for my art and I became more interested in research. It was a combination of things: the sociopolitical situation, ideas that I always had in mind but never executed, and the fact that I couldn’t take portraits of people because of COVID. This piece is a demographic portrait of the future of the United States. It reflects the 2011 Census data prediction for 2043, which states that all non-white groups combined will surpass the white population. The piece uses skin tones approximations from pictures submitted by participants across the U.S. Each one is placed in a square with their name, and each square holds an equal place.

VC: This is such an important issue to call attention to. A recent study showed that one in three adult Americans believe that the demographic decline of whites is intentionally orchestrated. These “replacement” conspiracy theories have moved form fringe to mainstream anti-immigration discourse and have even spilled over into actual gun violence…

KN: My work tries to spark conversations about these issues. In a very subtle way, it lures you into curiosity. I hope that people are open to trying to understand other people’s realities. In the end, todos estamos hechos del mismo barro (we are all made of the same clay.)

VC: Regarding your engagement with race in your practice, how have you had to contend with the legacy of racism in the U.S.? Did you notice a difference in the role that race plays in the cultural and political conscience in Latin America when you moved here?

KN: In my case, it was the microaggressions because I didn’t speak the language at the beginning, and also the internalized racism. As for your second question, I don’t think it’s much different, to be honest. The problem with Latin America is that they don’t recognize there is an issue with racism. Racist acts are naturalized but t I think it’s time to be more vocal about it. I’m starting to see some change. Slowly, at least in Argentina, they are calling these things out but there is still a lot of work to do.

VC: Having lived on the other side of the Andes, I think so as well—which is why I believe that the light and hope your work irradiates is so crucial. Karen, thank you so much for this interview. Before we part ways, I would like to ask you: If you could give one piece of advice to immigrant artists in the US, what would it be?

KN: Don’t lose yourself trying to fit in. Know the history of your country, your roots, and celebrate who you are. Knowledge is a powerful tool.

The author would like to thank Theo Brandt and curator Sofia Thieu D’Amico for the time and generosity given to the creation of this article.

1. DEMOS, T. J. The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis. Duke University Press, 2013.

2. JABLAN, SLAVIK, Modularity in Art, Visual Mathematics.

3. DEMOS, Ibid.

Vicente Cayuela is a multimedia artist working at the intersection of staged photography, sculpture, and installation. His handcrafted photo-based artworks create colorful scenes of graphic overload and tongue-in-cheek cultural commentary inspired by juvenile aesthetics and material culture. His work has been exhibited in New England most notably at the Griffin Museum of Photography, the St. Botolph Club Foundation, the Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, PhotoPlace Gallery, and published nationally and internationally. In 2022, he was awarded the Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the St. Botolph Club Foundation, in Boston, MA, and was one of the seven winners of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize. Cayuela holds a BA in Studio Arts from Brandeis University, where he received the Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography and the Deborah Josepha Cohen ‘62 Memorial Award in Fine Arts.

Follow Vicente on Instagram: @vicente.cayuela.art

Website: www.vicentecayuela.com

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Femina at Gallery 169February 20th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Reservoir: Loneliness, Well-Being and Photography, Part 2January 22nd, 2026

-

Reservoir: Loneliness, Well-Being and PhotographyJanuary 21st, 2026