Parker Thompson: Always Been

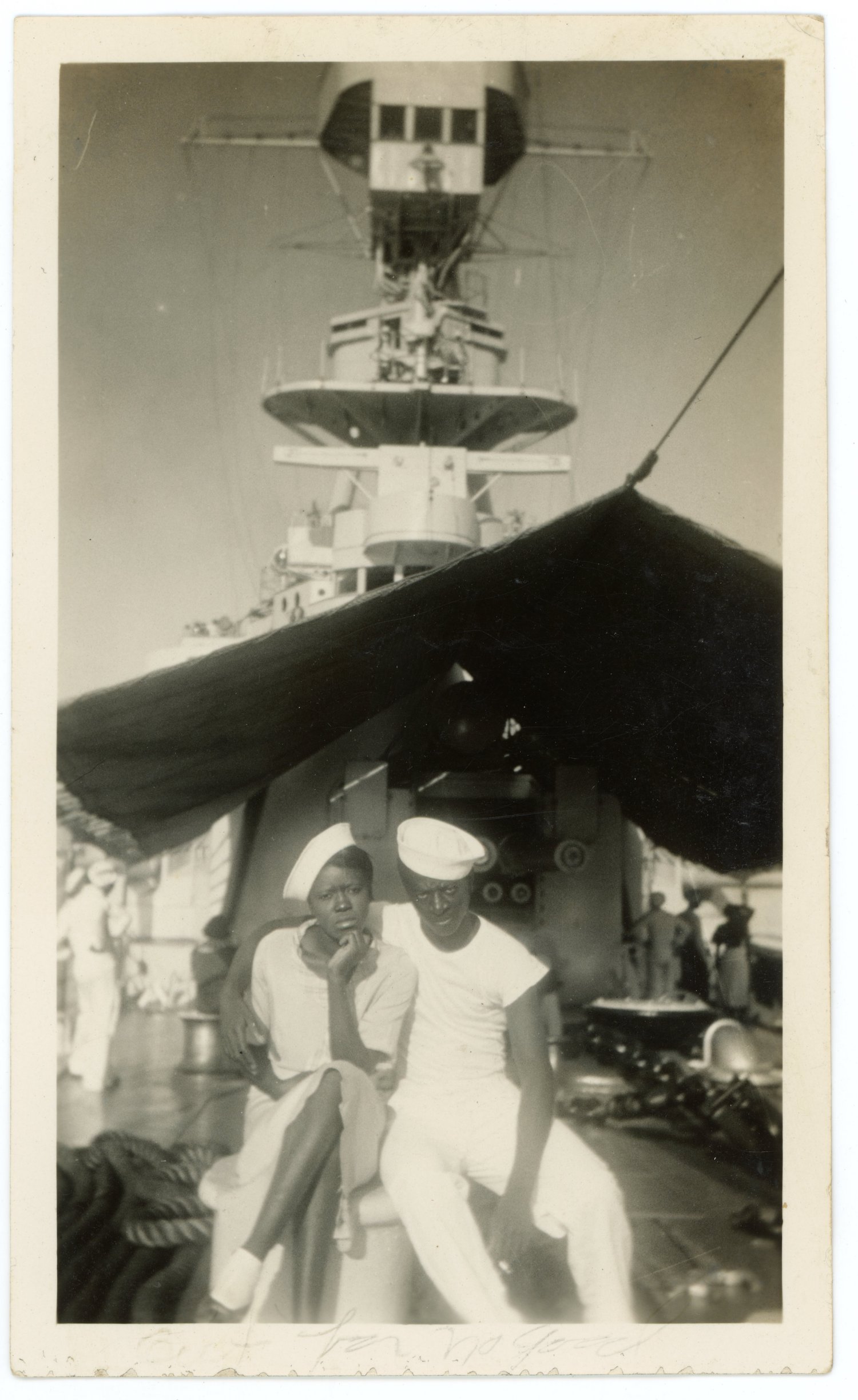

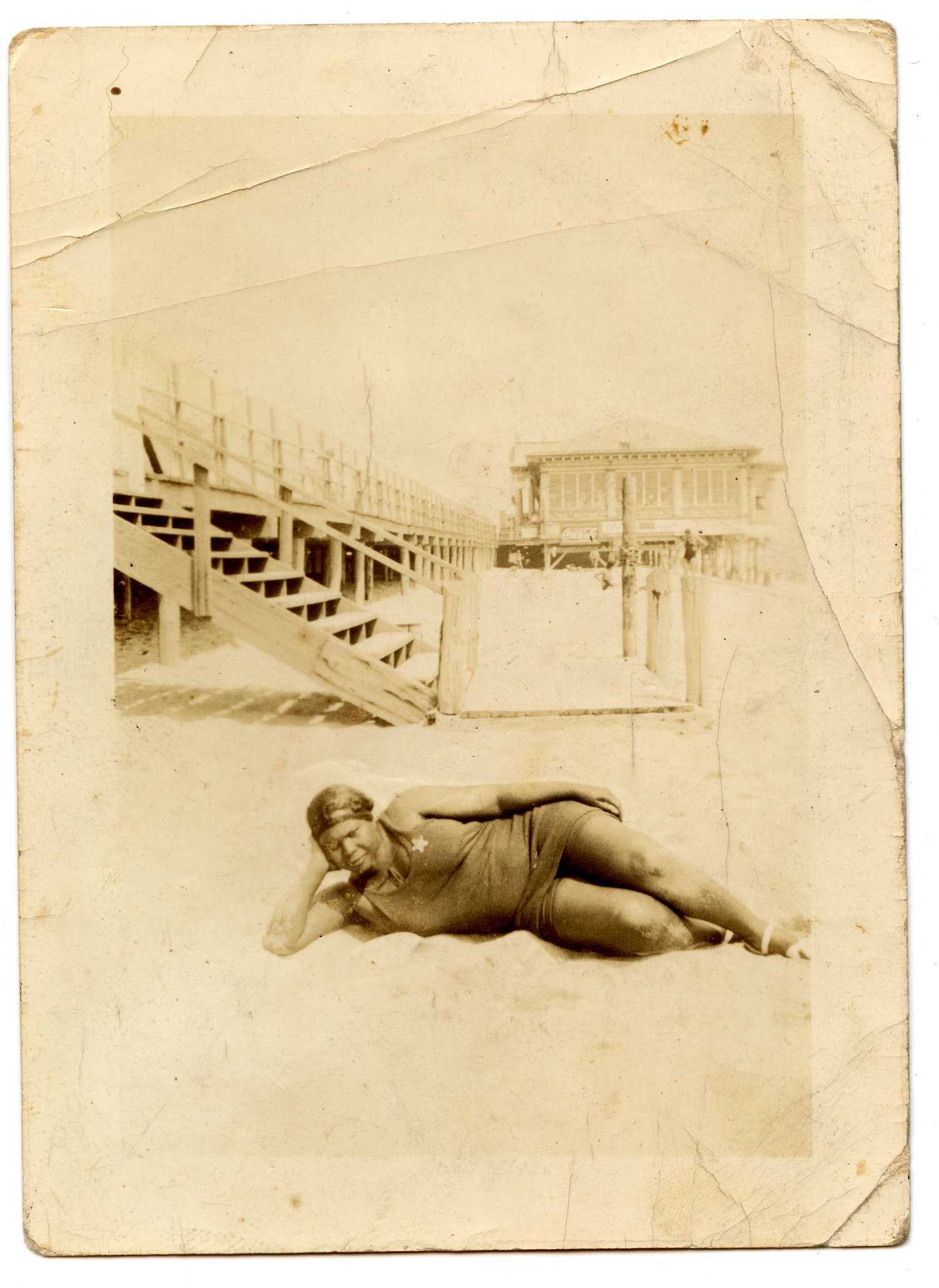

When Parker Thompson and I met at our university’s media lab, he was digitizing a collection of old photographs of Black life in America that he had assembled with meticulous care. As he generously showed them to me over the syncopated light beam of a wonky Epson scanner, it became immediately evident that he was onto something of immense cultural value. For who knows how long, the heartwarming array of snapshots was lost in the mists of time. Today they reach your eyes thanks to Thompson’s keen curatorial sensibility and his countless antique store adventures and bookmarked eBay tabs.

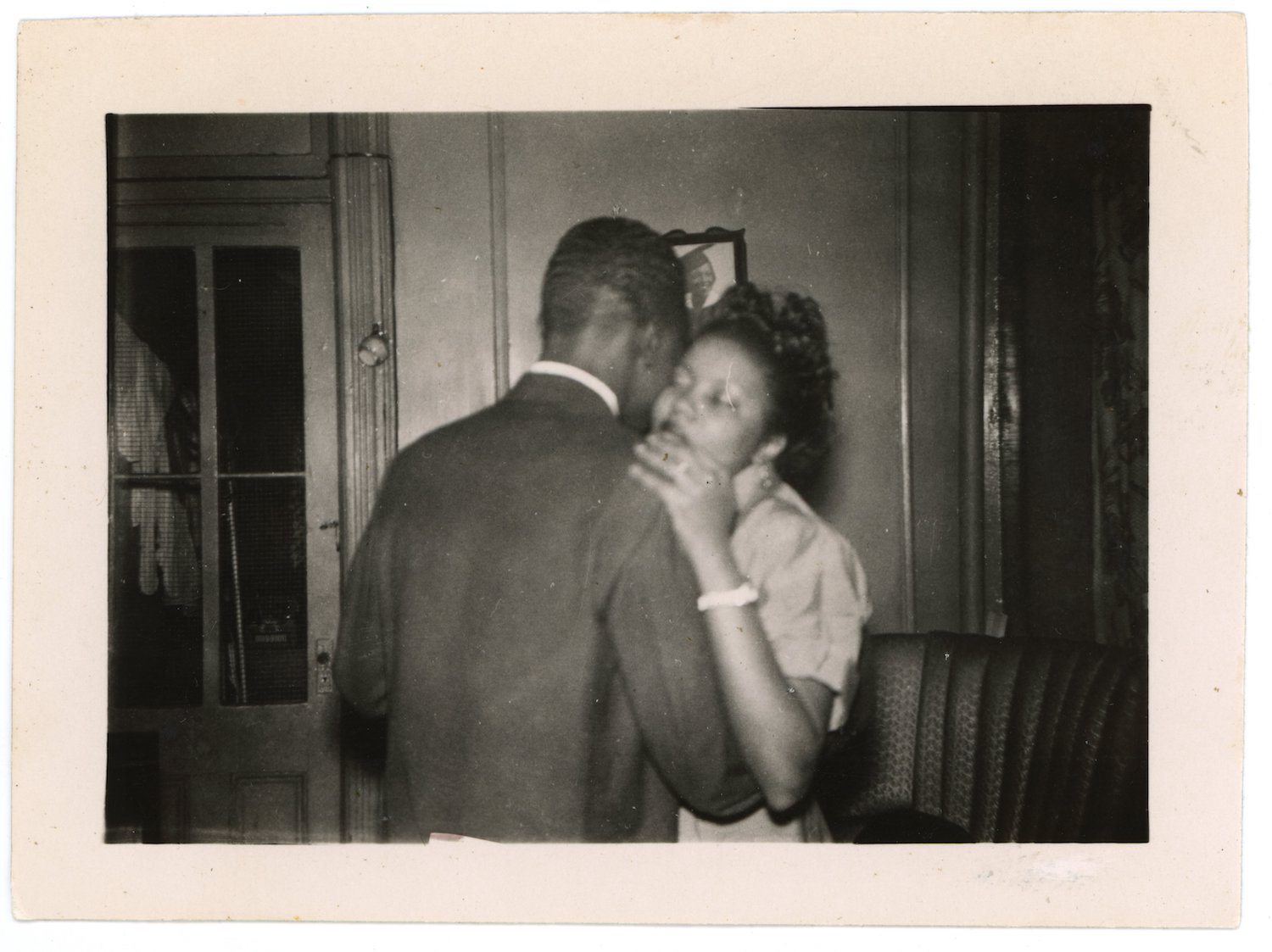

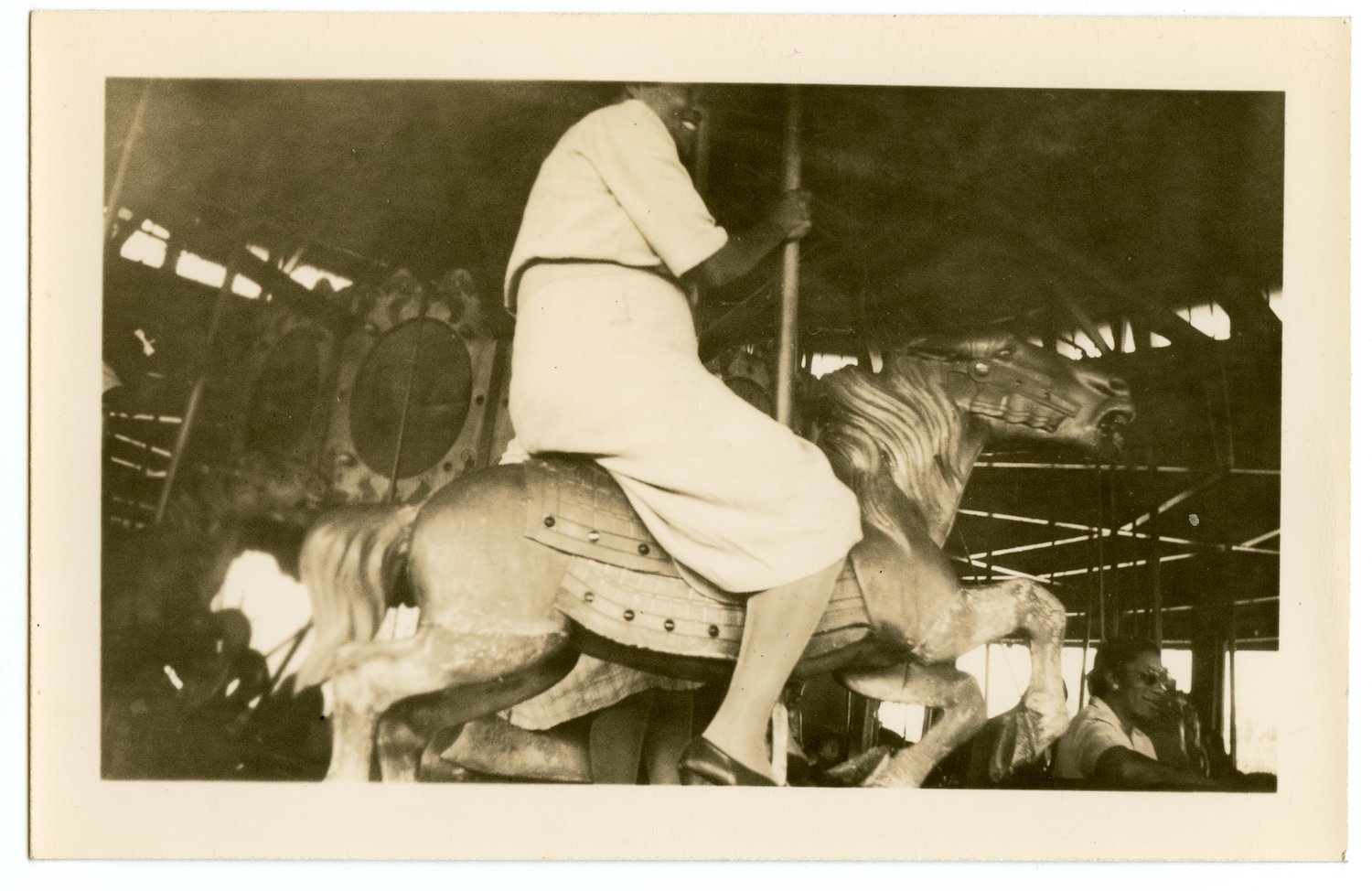

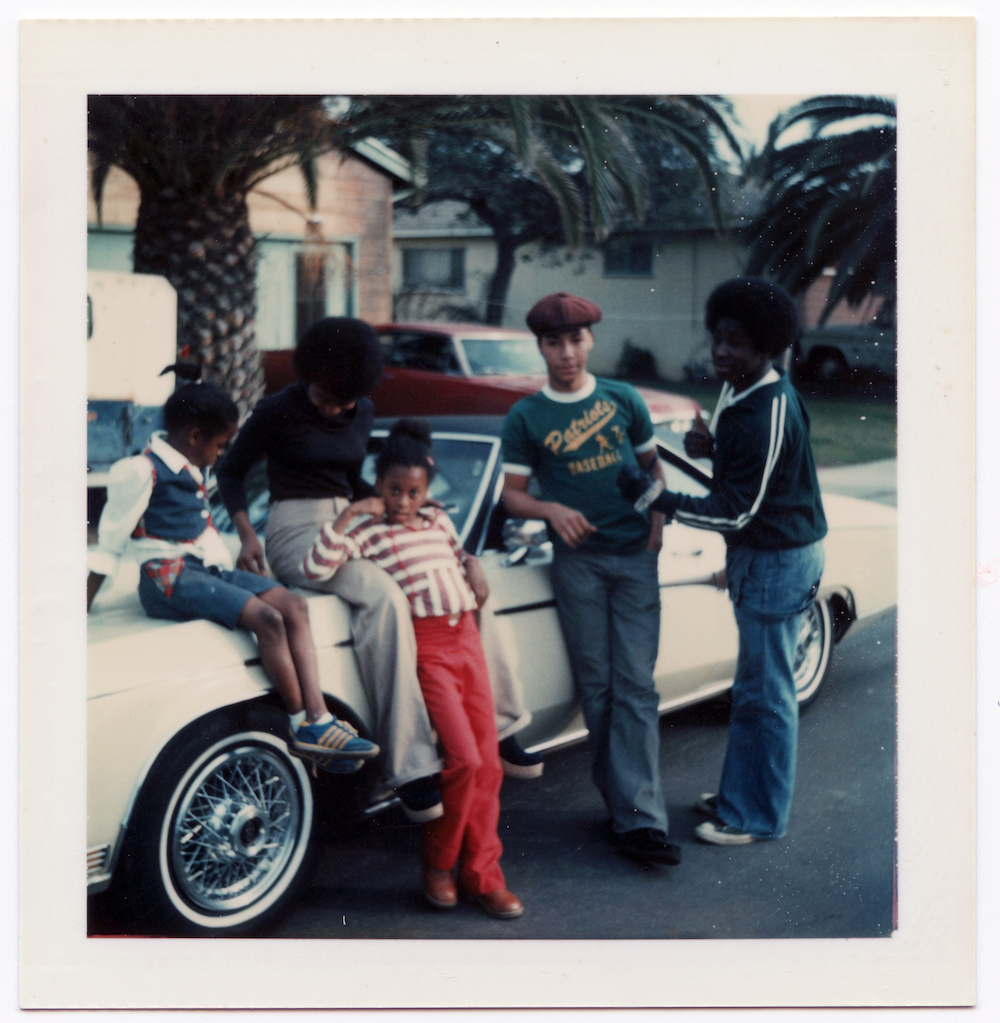

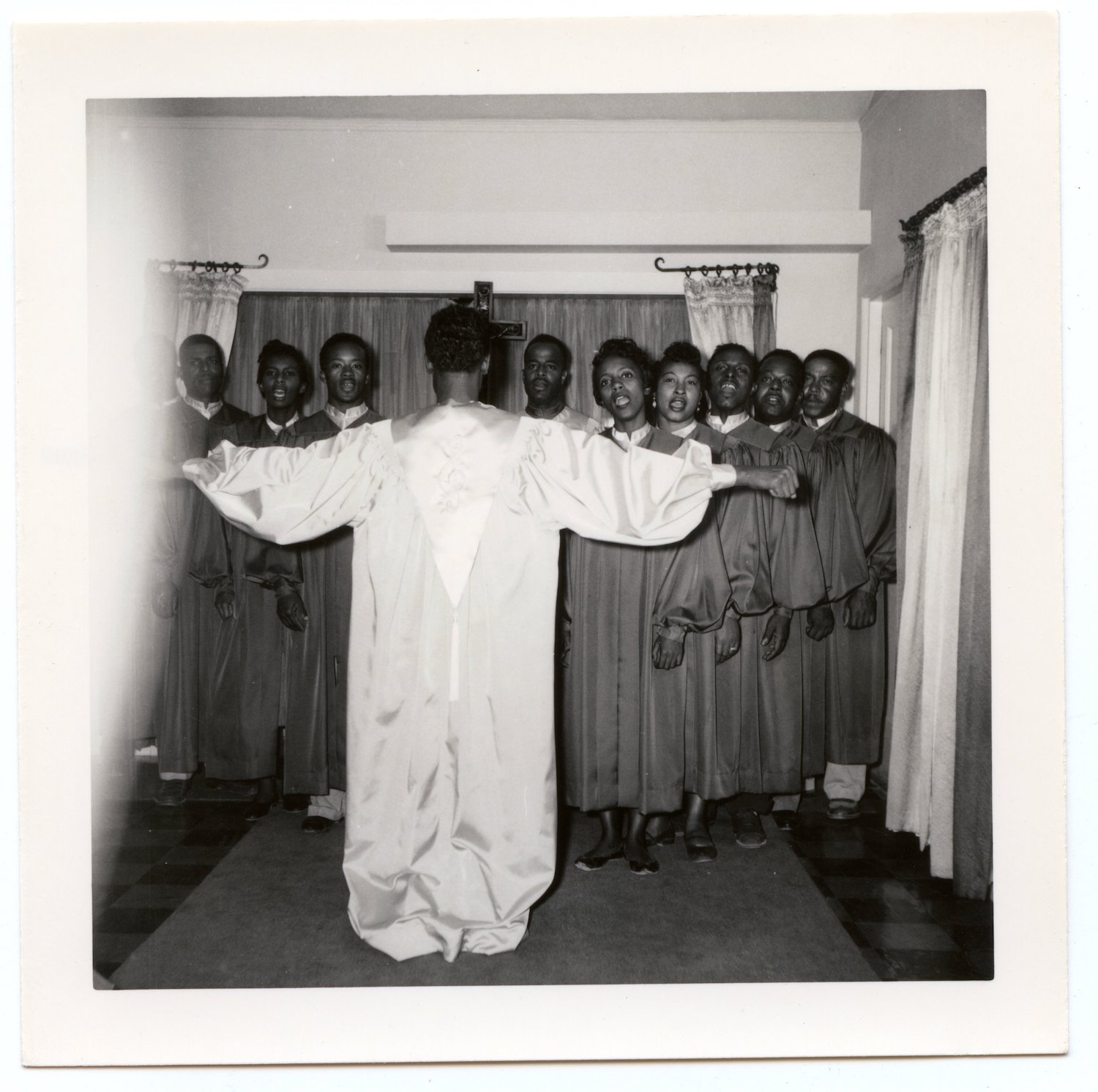

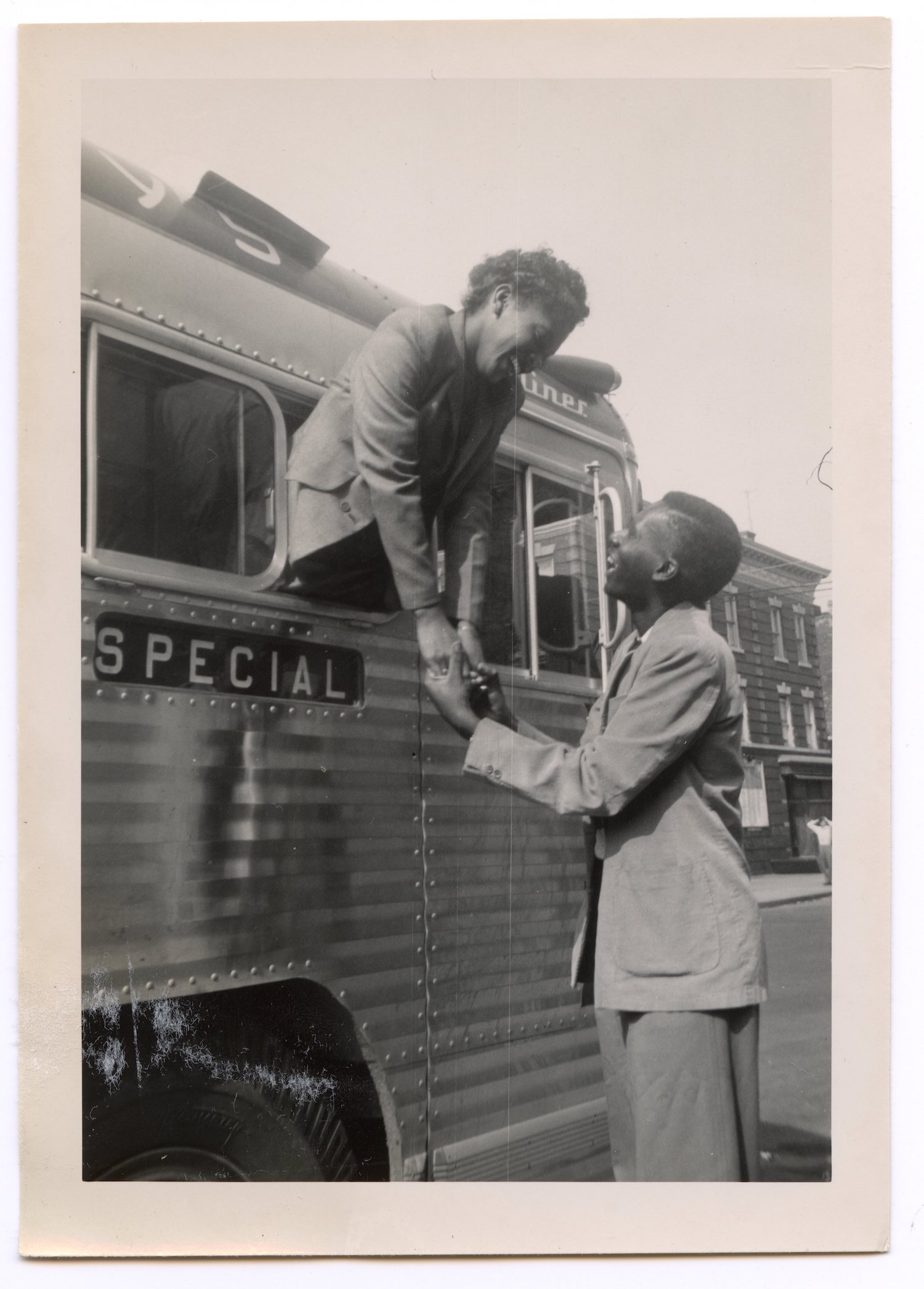

Always Been—the digital archive where these images can now be found—shatters the obstructive lenses and pervasive canons through which generations of Black Americans have been stereotyped and dehumanized in photographic media. In our era of polarizing politics—and in the contemporary photographic landscape—few projects of counter visuality take such a meaningful and celebratory approach to historical accountability. Each photo brims with love and exudes the almost palpable reverence that undoubtedly went into their creation and rediscovery. Today’s interview celebrates that love and everyday people—the vital forces from which culture originates. Only this embrace with its generative power can expand our public memory and collective history to encompass everybody for who they truly are.

Thomson’s curatorial debut, Intimacies, Long Lost: Selections from the Always Been Collection, is currently on view at the Griffin Museum of Photography in Winchester, MA, from January 12 to February 26, 2023.

Always Been is made possible with generous support from the following institutions and programs: Fori and Robert Kay Creative Collaborations, Maurice J. and Fay B. Karpf and Ari Hahn Peace Awards, Provost’s Research Fellowship, Brandeis University, The Tauber Institute Social Justice Initiative.

Parker Thompson

Parker Thompson is a photographic researcher, collector, and student based between Charleston, South Carolina, and Waltham, Massachusetts. He is the curator behind Always Been, an archival and curatorial project focused on the humanity, dignity, and joy of Black life as seen through the lens of snapshots and vernacular photographs. He is currently studying history at Brandeis University.

Always Been: Celebrating Black Selfhood and Joy Through the Magic of Found Photographs

“It is a more arduous task to honor the memory of anonymous beings than that of famous persons. The construction of history is consecrated to the memory of those who have no name.”

—Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History

Vicente Cayuela: Parker, I have been wanting to interview you for over two years. I am so happy that we get to present your work to the Lenscratch audience. I think everyone should know the amazing curator behind this critical and restorative archive. Can you tell us about Always Been?

Parker Thompson: Vicente, thank you for having me! Always Been is deeply entrenched in my own personal relationship with photography, family, and race. I grew up in the American South (Charleston, South Carolina) and, as a bi-racial but often white-passing person, felt alien in my body for most of my life. Compounded by an uncontrollable distance from much of my family, I was lost when I wanted to explore my relationship with Blackness more deeply. All throughout my teenage years, I immersed myself in the world of fine art photography and eventually discovered the world of snapshots and so-called “vernacular” images—essentially any picture made for non-artistic purposes.

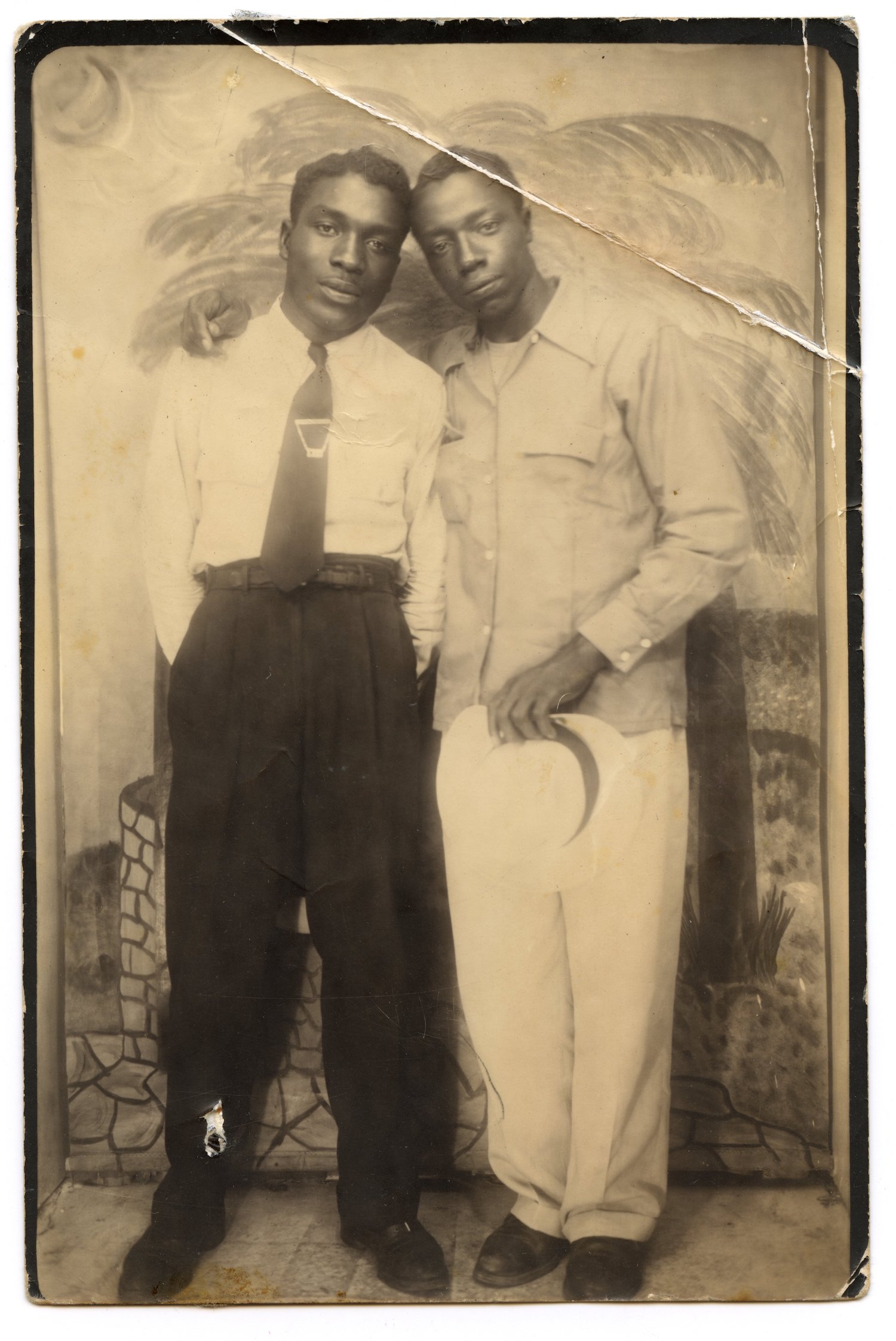

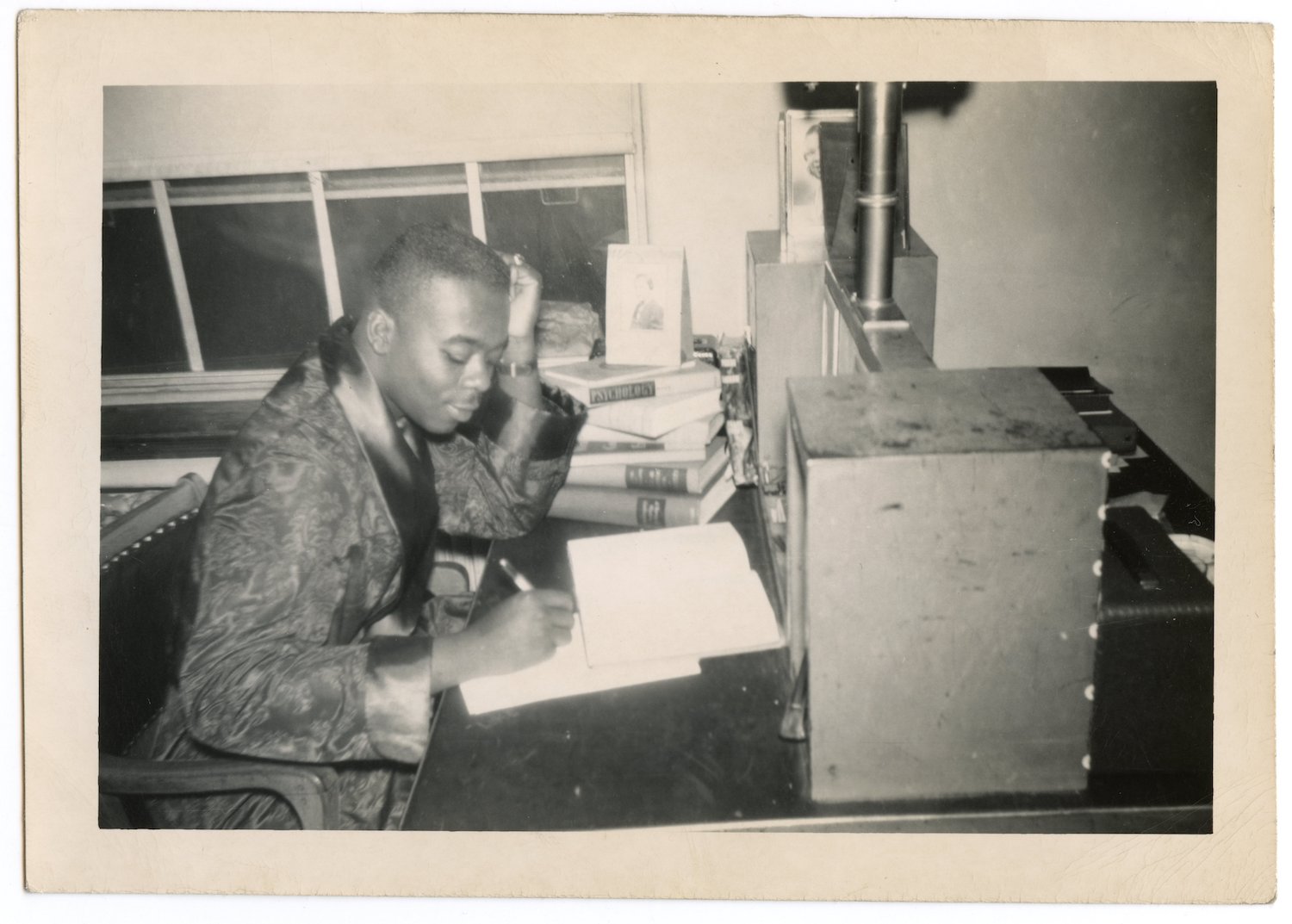

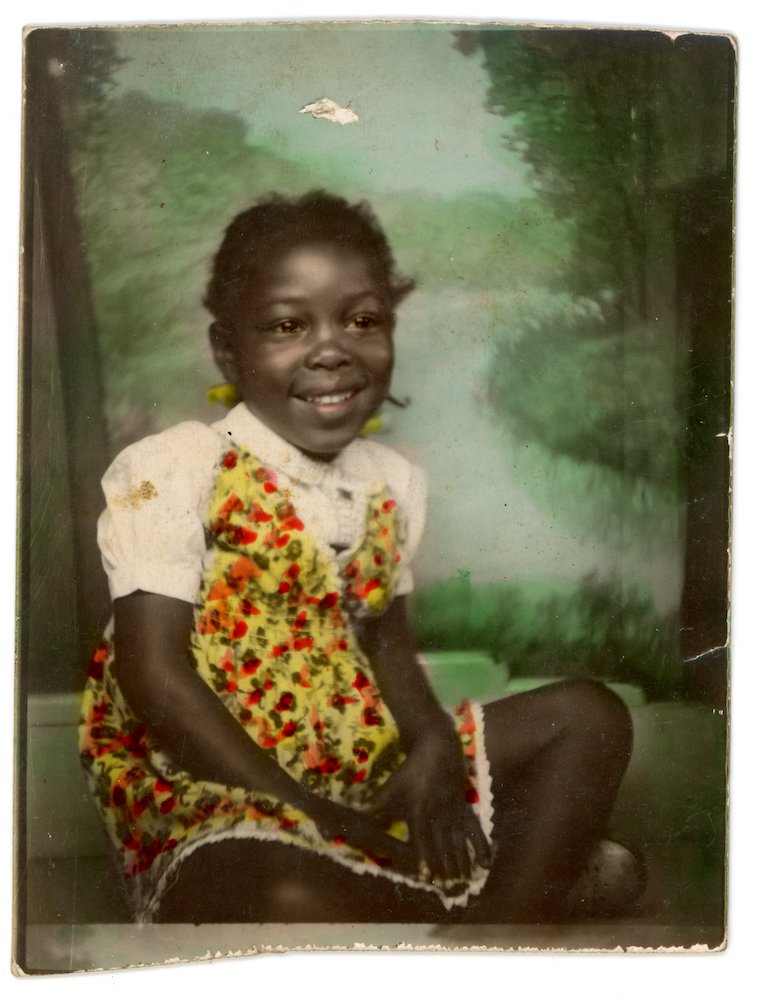

Browsing snapshot images online, it didn’t take long to realize that the snapshot, just like fine-art photography, was overwhelmingly white. I began to explicitly seek out snapshots of Black life which unleashed a sort of avalanche that has thrust me deep into the sparsely-explored world of Black everyday photography. I found that the images I saw were not only personally compelling but rich with personality, history, and visual culture. More than anything, the reformation of Black visual history is at the core of Always Been. A specific set of narrow representations pervade the visual history of American Blackness and overwhelm popular consciousness. The snapshot and its vernacular counterparts, which make up the collection, are essential tools through which we can better understand Black imagination, selfhood, and, more broadly, history.

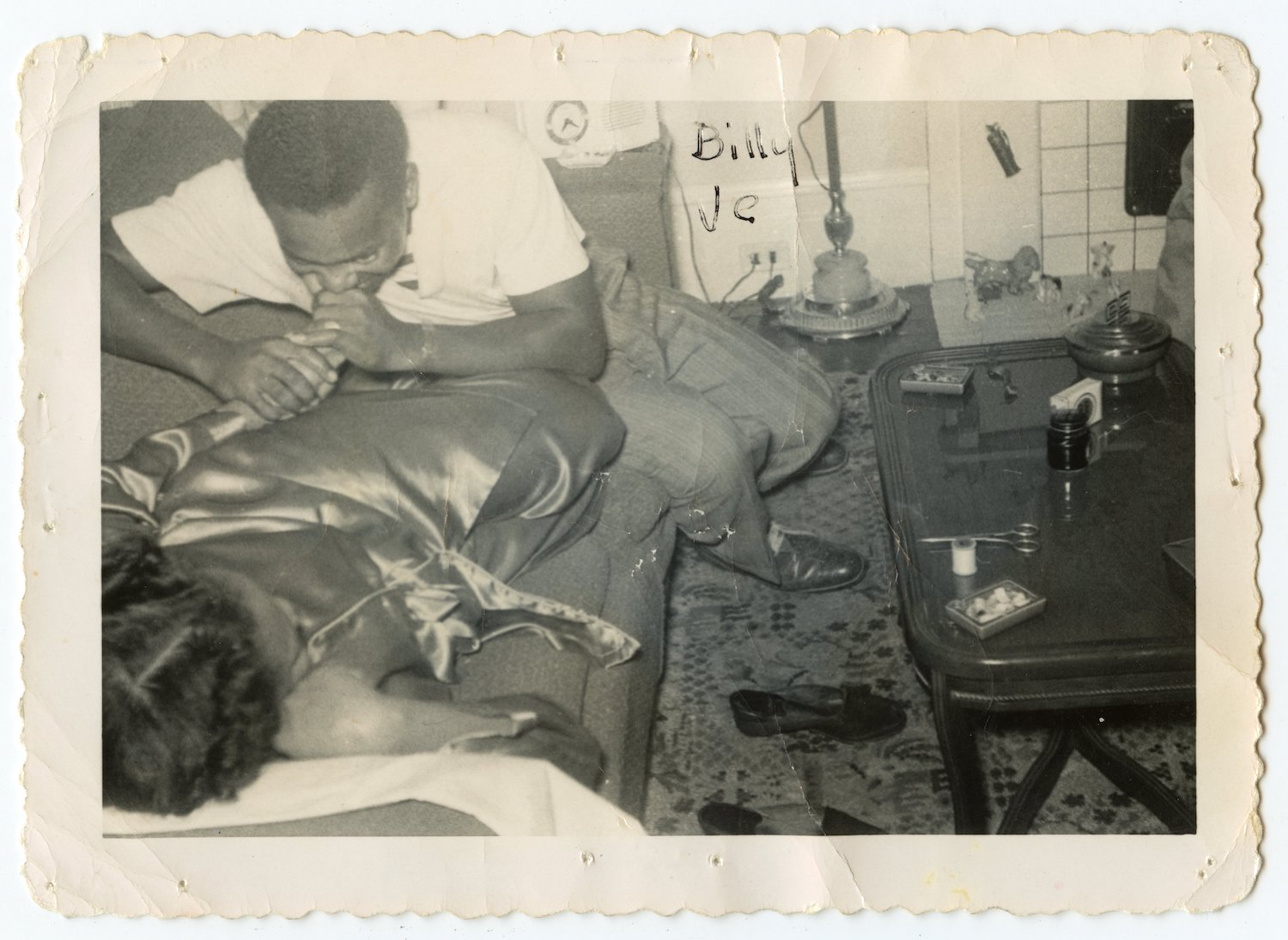

VC: Thanks for sharing those intimate details about yourself. I could spend all day looking at these candid registers of families, lovers, and friends… How do you go about finding these? And what do you look for in a photograph as a curator?

PT: I often find the answer to your first question quite embarrassing, but really it’s incredibly important to understand and contextualize the work of Always Been. A few come from Etsy, a handful are found and mailed in, but the vast majority come from one source: eBay. There is a very layered marketplace on eBay for all kinds of snapshots with over one million listings that is deserving of its own dissection one day. There is a not insubstantial marketplace actively dealing in lost and missing photographic memories of all kinds—it’s a complex and questionable world, to say the least. When it comes to a photograph entering the collection, I tend to look for those pictures which push the visual conventions of Black history and collective imagination. I am also especially attracted to those images that show a deep engagement with the camera and the act of making a picture.

VC: I love what you say about expanding descriptions of Blackness in the collective imagination. Given photography’s past, we must remain critical of these “by who” and “for whom” conundrums as photo-based artists and curators. Would you mind elaborating on how the white visual and cultural hegemony has created distorted representations of Black people, especially through photographic media?

PT: My primary thinking about the snapshot is informed by my belief that photography is historically grounded as a tool of control and subjugation. From its earliest beginnings, the daguerreotype was incredibly popular among the upper echelons of Southern slave societies, and some of the earliest known photographs are those taken of enslaved Black people. Those roots grew with photography all throughout the 20th century, and as a result, the images that dominate Black visual history are those that depict segregation, brutality, and political struggle. While those facets of American Blackness are undeniably crucial to our history, the predominately white visual culture has only continued to exercise undue control, erasing the equally—if not more significant—everyday existence that is captured in snapshots from our history and consciousness.

VC: You put that so perfectly. I spend a lot of my time musing over the histories that collecting institutions choose to preserve and whether they can truly offer the “closeness to culture” that they profess. Given that culture starts with the people, how can collecting institutions engage with this intimacy? And why is it so critical?

PT: When we look at the acquisition and exhibitions of snapshots and vernacular photography in particular, we see a very limited, conservative approach. I understand the hesitancy of many museums to take on these small, abundant images that, at times, have very little or no relation to art, but ignorance about this medium has pervaded the system. I can only hope that museums and cultural institutions, especially those not already doing significant work for and with American Blackness, will re-examine the significance of the Black every day, especially with attention to snapshots, vernacular photographs, and those artists who closely work with the material.

By looking at and interrogating snapshots, we can understand how Black people and Black communities have imagined themselves in their most authentic form. We can see their vibrancy displayed free from outside gazes. We can move away from the predominately white visual culture through them—understanding the agency that not only exists for us now which is being used powerfully in Black communities but also remarkably existed a century ago. In my mind, snapshots are really the closest, most authentic visual representations that we have in the medium. While some might point to photojournalism or documentary photography, I believe the intentions and imagined spaces that exist in the snapshot realm are far more clear and get us as close as we can to “real” representations.

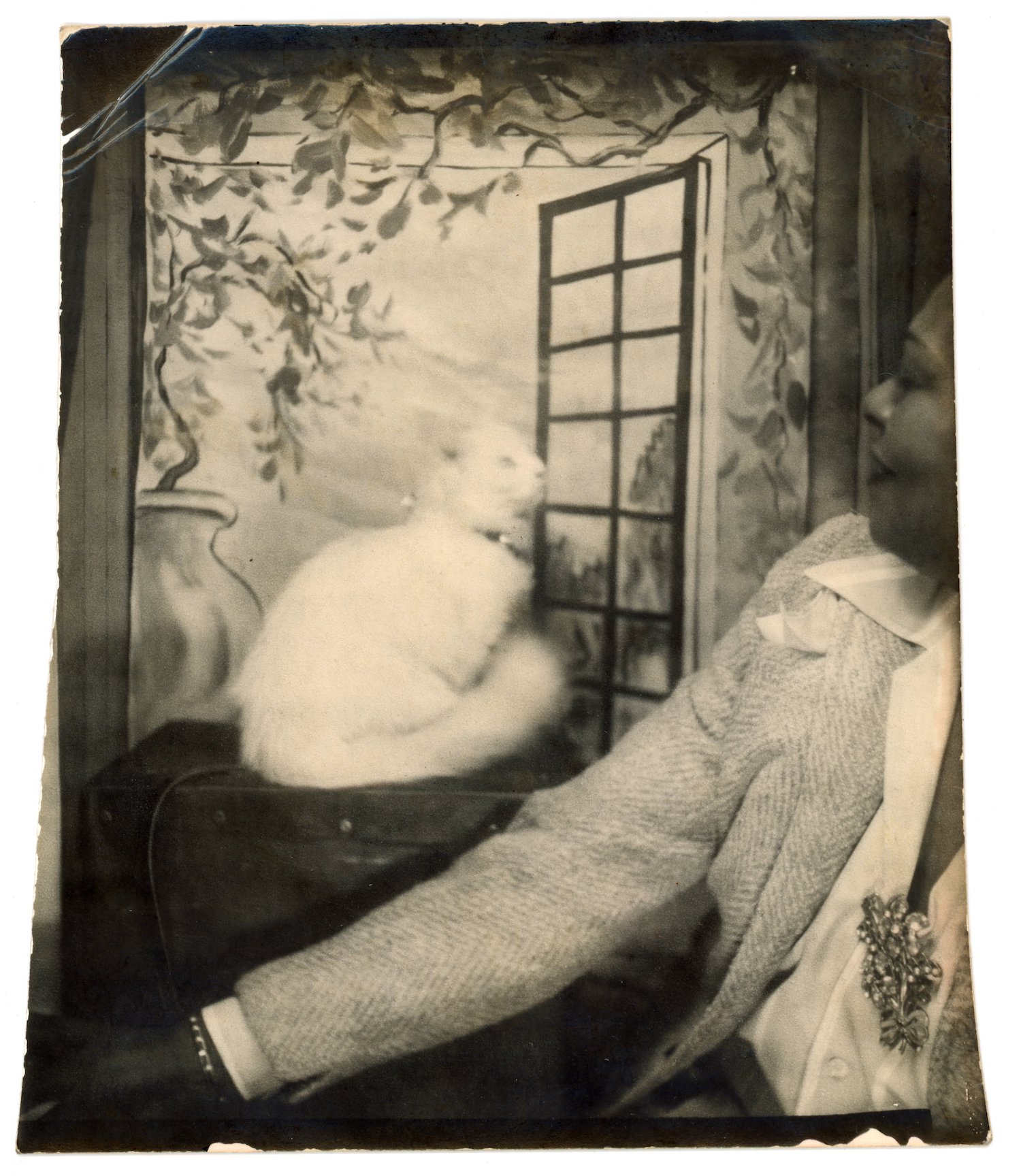

VC: What’s your favorite photograph from Always Been?

PT: I feel as if this should be a hard question to answer, but I really don’t believe it is. There is one particular image, a larger-than-usual photo booth print, of a woman and her cat, a seemingly simple concept that turns out to be representative of everything important about the snapshot. It’s a remarkable image, this woman and her blur of a cat gazing longingly at each other. I can’t imagine another picture that could communicate the complexity, beauty, and significance of the snapshot and its “vernacular” counterparts.

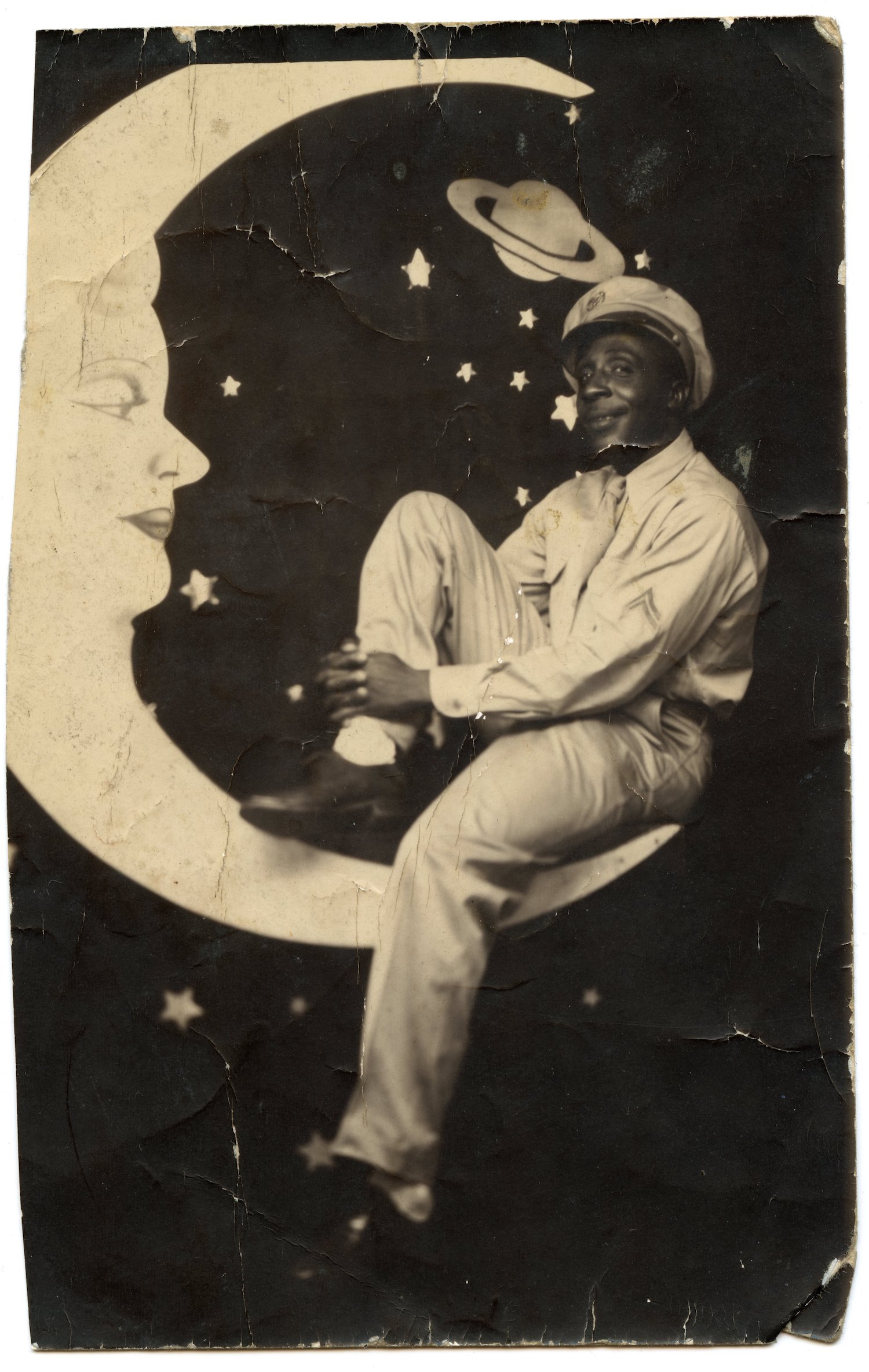

VC: This picture of a man in a studio setting is fascinating. Why did you choose to collect this photograph and can you tell us what you know about its historical context?

PT: This particular photograph is an example of a popular visual set piece used in 20th-century studio photography: the paper moon. Appearing first in the late 19th century, the moon sets grew massively at the turn of the century as popular culture took interest in the “romance of the moon.” As you can see in this particular image, the paper moon is an undeniably playful setting through which the sitter may situate and present themselves. Many of the moons were personified with facial features, increasing their photographic potential – moving the studio photograph away from formal portraiture and toward a more dynamic range of pictorial opportunities. I have found that paper moon photos with Black subjects are remarkably difficult to find, and when I saw this listing, I actually cried. In fact, I have the moon from this particular photo tattooed on my left arm.

VC: In addition to being a prolific collector/curator, you’re also an avid reader. While historically understudied, there is a growing popular and scholar interest in Black photography. Can you give us some reading recommendations?

PT: Absolutely. As a starting point to understand Black snapshots, I am practically required to point you to bell hook’s remarkable, very consumable essay In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life. The anthology Picturing Us, edited by venerable photo historian and artist Deborah Willis, is a must-read. For some historical approaches and background, Matthew Fox-Amato’s Exposing Slavery and Catherine Zuromskis’ Snapshot Photography: The Lives of Images. Lastly, the very recent To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness by Robin Coste Lewis—it’s an astounding combination of poetry and snapshot.

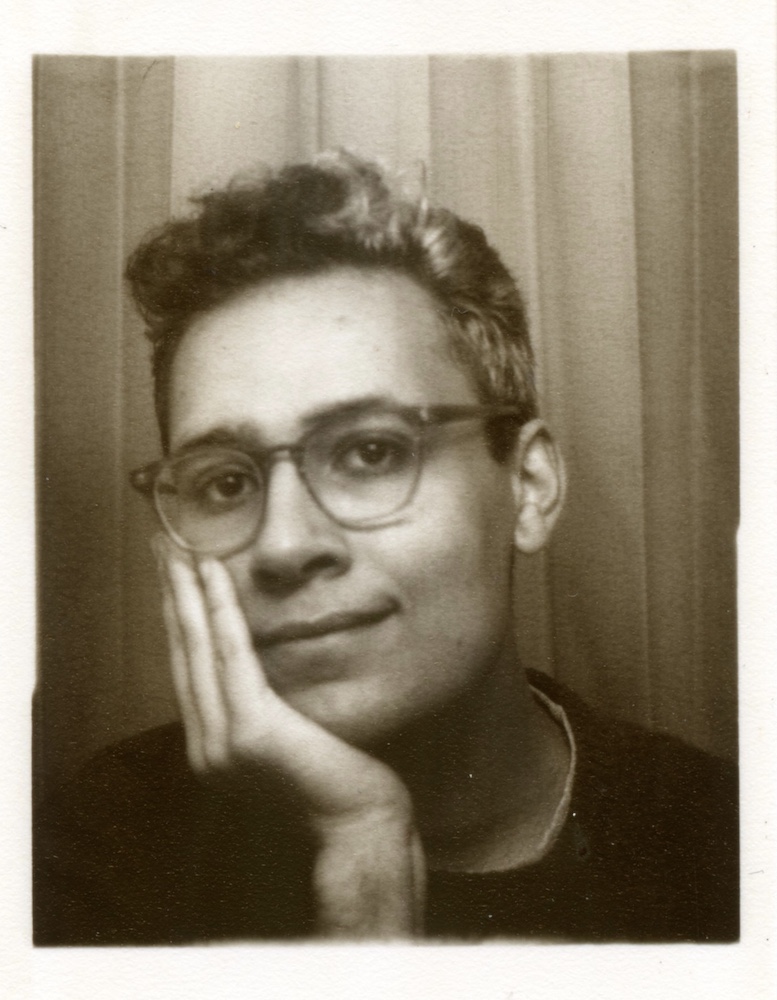

VC: Parker, thank you for sharing some of the highlights from your collection. Before we part, I also see a portrait of you. You are daydreaming and gazing into the horizon. What’s in store for Always Been? And for yourself?

PT: Really, I wish only to be surrounded by pictures and by people who love and appreciate them. Maybe that is in a museum or an archive, but maybe it is an entirely different world; as long as I am looking and thinking, I will be happy.

Vicente Cayuela is a multimedia artist working at the intersection of staged photography, sculpture, and installation. His handcrafted photo-based artworks create colorful scenes of graphic overload and tongue-in-cheek cultural commentary inspired by juvenile aesthetics and material culture. His work has been exhibited in New England at the Griffin Museum of Photography, PhotoPlace Gallery, the St. Botolph Club, and the Abigail Ogilvy Gallery, and published nationally and internationally. In 2022, he was awarded the Emerging Artist Award in Visual Arts from the St. Botolph Club Foundation, in Boston, MA, and was one of the seven winners of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize. Cayuela holds a BA in Studio Arts from Brandeis University, where he received the Susan Mae Green Award for Creativity in Photography and the Deborah Josepha Cohen ‘62 Memorial Award in Fine Arts.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025