On Finances and Accessibility: Drew Leventhal and Alayna Pernell in Conversation

This conversation with the fabulous Alayna N. Pernell felt like a breath of fresh air. Discussions around money and finances and costs can feel awkward and taboo. We have been taught that it is impolite to compare pay or talk about where somebody gets their money. These are conversations that can feel dark and dirty.

It is time to bring them into the open. It is time to create transparency around finance and money in the photography world. In the past few decades, the art photography community has become a more diverse and accepting place (with so much more work to do) but we still have a blind spot when it comes to socioeconomic class and wealth. The truth is we are failing young and emerging artists. The financial barriers to enter into the contemporary photo world can be insurmountable. Gear, degrees, applications, reviews, workshops all siphon the often meager pay artists get freelancing or teaching.

This conversation is not a list of grievances. It is not perfect. It is a specific story. It is a call to action, a call for transparency, and a call for change. It is a start. My hope is that by sharing experiences and conversations like this we can see gaps in our vision, places where we fall short, and where we can do better to help one another. –Drew Leventhal

Drew Leventhal: Alayna thank you so much for sitting down to talk with me, I am very excited.

You graduated with your MFA in 2021. I want to start there and ask what it was like when you first got out of school? It can be a jarring experience to leave the challenging but safe environment of the academy and find your way in the real world as a young artist.

AP: It was really scary. I remember crying the night that I graduated because I didn’t have a job lined up. I was thinking to myself, ‘I should be really happy, but I’m not’. So I kind of floated around that summer babysitting, hanging out with friends and doing fun stuff around Chicago. I didn’t get a job until two weeks before I was making the decision that I needed to go back to Alabama.

DL: You were about to leave Chicago and go home.

AP: Yes, I got an adjunct position as a photography instructor two weeks before I was about to leave, but it was also less than three weeks before the semester started.

DL: You got thrown in the fire a little bit with no time for you to prepare. I’m just curious if you can talk more about the experience of that first adjuncting job and how it went.

AP: When I got the job I was so excited that I was given the opportunity to teach. I honestly didn’t pay attention to how much the pay was going to be. All that I was thinking was ‘Oh, I have a job now. I can stay in the Midwest and it’s gonna be great.’ Quickly after my first semester I realized a lot. The first thing I realized was that I had quite a heavy teaching load. I’ve been teaching three classes every semester.

DL: A 3/3 in academia terms.

AP: Exactly, which is a lot on top of not getting paid very much for it. Things like prep time for class, the expectation to show up for students outside of class and more are not well accounted for in the pay range. It is different from being a student where there’s a lot more resources that are given to them. If a lot of those resources were equally provided to faculty members and especially adjuncts who are teaching, it would make a big difference. Not to mention, the majority of adjuncts (myself included) have to work another job to stay afloat. That was a hard lesson for me and it’s still a struggle.

DL: Your point on resources for adjunct faculty is spot on and seems like something very doable. How could we expand already existing resources to adjunct faculty, treat them more like the essential and valued employees that they are?

I want to hold onto your thoughts about transparency and adjuncting. I appreciate you saying that these are uncomfortable conversations around finances and inequality. They’re not easy but it’s important to talk about it openly. It’s important to recognize that adjuncting as it exists now is not a sustainable living in many places and I think that needs to change because the structure can not hold much longer.

AP: I agree. I actually have a question in return for you. Are there different resources that you’re given at RISD? I’m so curious about if this is a school by school thing or if this is a nationwide problem.

DL: I would say it’s pretty similar across the board. There’s a fundamental divide between how much money is coming in and how much goes out in terms of sustaining a practice. We can do better for our adjuncts, especially as we increase the number of them. In academia more broadly, there’s so many more adjuncts now than there were even 10, 20 years ago. It’s a model that is unsustainable for these young faculty.

I will pivot to talking about trying to balance work and practice, always a difficult challenge. I’m curious how you have made time for your practice outside of your teaching and also your other jobs. How do you find the time to make your work or think about your work?

AP: I think balance is actually a really new thing for me since last summer. My first year of teaching I had completely neglected my practice and I despised that. I went months without even touching my camera. This isn’t to say that I wasn’t thinking about art or engaging with it, but I wasn’t at the level of creativity that I was at before teaching. When the fall semester hit, I became vocal with my students about my availability and set hard boundaries about when they could reach me and when I was going to be unaccessible. I had to set that boundary because I’m actively learning how dangerous it can be to have a set salary or stipend versus an hourly wage. It’s so easy to take advantage of someone if you are not paid hourly.

DL: A little bit of time here, a little bit of time there. It adds up to more work for less pay.

AP: Yeah, exactly. Setting boundaries has been really fulfilling and I’ve been able to create and do more than I did my first year of teaching. I refuse to neglect my practice like that anymore because I’m an artist first and teacher second– maybe even third these days.

DL: I want to think now about the costs of building a career as an emerging artist. A lot of that career building is done through portfolio reviews or applications for competitions. All those costs and application fees are very expensive and they can quickly add up to become prohibitive to artists already struggling to make a living. I know that the photo centers and organizations that run these events are also strapped for cash. But I’m wondering how we can figure out ways to incentivize younger artists, artists of diverse backgrounds of all types, to participate in these spaces that can be really financially inaccessible. Do you wanna talk about your experience with those kinds of costs and also how can we theorize alternative models?

AP: In my second year of grad school, I made the decision that if something had an application fee that was more than $10-$15, I was not going to apply for it. Even with my students, I do not share opportunities with them that have a price tag on it because they should be free and as a student funds are tight. Several of my career opportunities did not cost me a dime. I run away from applications that have the structure of paying $30 for a set amount of images and then an additional cost for adding more images to be reviewed. I don’t understand where the cost comes from. It’s both terrifying and disheartening. I think there either needs to be a reconfiguration of budgeting or fundraising for other sources of money to help mitigate fees.

DL: I fully agree with you. In a way it feels slightly vampiric, relying on application fees from artists who may not be able to afford them. This is where fundraising, from donors and/or board members, has to step up.

AP: In a way, expecting people to pay large amounts of money for something is another way of prioritizing privileged artists…

DL: Yes, exactly. And I think it’s a really good example of how organizations are missing a huge swath of extremely talented younger and emerging artists because they can’t afford to buy a membership or pay the application fee. You’re missing so much, cutting so many people out of the conversation, and pigeonholing yourself into only selecting certain kinds of photography.

AP: You can be an incredible artist and still not have a lot of money. That is the case for a lot of people. So if you’re going to be an establishment that is open to all, being open to all should not just be based on race, gender, sexuality, etc., It should include the financial aspect as well.

DL: Absolutely. I think the photography community, more than most worlds, has been trying to be more accessible and accepting. But there’s a huge hole in terms of talking about socioeconomic inequality and financial accessibility. And it’s just a missing thing that people aren’t talking about because it can be uncomfortable. So what are some solutions?

Something that feels like a realistic start is just focusing on transparency and dialogue around these topics. A lot of these competitions, you know, they’re getting application numbers in a range of 200 to 300, maybe up to 1,000 if you’re one of the bigger ones. I think there should be a part of these submissions that asks, ‘Hey, are you gonna have trouble paying for this application fee? If so, tell us why and we will work something out.’ That is a very simple thing but it would go such a long way towards helping.

AP: I agree with you. It makes me appreciate the organizations that don’t have submission fees. We are speaking for a Lenscratch article right now, but even if we weren’t, I would bring this organization up as a wonderful model thanks to Aline Smithson. There are no submission fees and they still do a phenomenal job of supporting artists.

DL: Again we have to recognize that these things do cost a lot of money to put on and require a lot of logistical coordination and a lot of labor. It is an issue I have not found a solution for, it feels like an impasse. It’s this fundamental question: how do you create and support/fund an equitable photography community? Every solution I come up with has massive ramifications and issues. Maybe you have one off the top of your head?

AP: I wish that artists were paid to be artists. That could be a start, though I don’t know if that would backfire if the government made us prove that we’re artists in a nonsensical way.

DL: What’s interesting is they actually have started to do that a little bit in Ireland. Just recently. It’s a pilot program that the Irish government started this year. They chose 2,000 artists and they gave them $350 a week. It’s a stipend from the Irish government to be an artist.

AP: I love that.

DL: That sounds amazing to me. Already some of the artists that they chose were saying it was life changing. They had time to make their work, photography, sculpture, whatever it is. They didn’t have to take a second, third, fourth, job. So maybe the answer is federal funding for the arts again.

AP: That sounds incredible. It should be what we do here in the states. I can’t help but acknowledge that in comparison to other media such as painting, sculpture, etc. that have been around for ages, photography’s only been around for a blip in time. That may or may not play a role with the push for accessibility of photography and photography opportunities. Though I do question if this part of the “why” behind there are almost always costs. Is there gatekeeping at play?

DL: You hit on a really interesting point, which is that photography prides itself on a low barrier to entry. Anyone can have a camera. I have a camera right here on my phone. Anybody can take amazing pictures. But like you just said, there’s a huge amount of gatekeeping that happens in the art photography world that I think primarily revolves around financial structures. That feels fundamentally at odds with our view of photography as the most accessible medium, the idea that anybody can be a great photographer. It’s become: anybody can be a great photographer, if you can pay for it. We claim to be accessible, let’s make ourselves accessible.

AP: I agree. I talk about these things with my students a lot because I try to mimic what I would like to see in the real world. I have this thing where I have my students give artists presentations. They pick an artist that they like and I tell them it can be any artist that they want. It doesn’t have to be an artist that is so famous they have a Wikipedia page. I’ve seen people bring in YouTubers. I’ve seen people bring in bloggers or people who aren’t necessarily on Instagram or renowned, but they are just photographers who have really great careers just in a different sector of photography. All of this variety can be appreciated and celebrated.

DL: It’s true though. The more we have these conversations around money and class the easier it becomes. So I’m wondering if this is something you do with your students or if it’s something you would be interested in doing with students, is when they’re researching these artists if they can find information about how they made a living. Between the point where they started their art career and successful or sustainable. In that gap, which I feel like is the space you and I are in right now, there needs to be more transparency.

AP: It isn’t currently, but I’m going to add it. I appreciate anybody being open about finances. A lot of people don’t like to share how much they’re making, but if it’s not shared, you get stuck in this cycle where people continue to accept what they’re given. I know The Luupe has made a section on their website where photographers show how much they charge for the services they’re offering. It shows other people both how much they should charge to take care of themselves but also shows companies that anything below a certain amount is not acceptable. This model of transparency is important.

DL: I think we are going to have to wrap up for now. Hopefully this conversation is just a starting point. This is a call to action because I really think that we, as younger artists of this new generation coming up, can take charge and can make new paradigms happen. The photo world doesn’t work without us. It doesn’t work without our labor. It doesn’t work without us teaching and working at art centers and applying to things. The photo world needs us just much as we need them.

AP: Very true. We have a lot of power. My closing point is reiterating the importance of being transparent about how artists are living in that space between emerging and established. Also, expressing more gratitude is a great place to start; especially for places that are already working and thinking about these issues. Lenscratch is a great example again, they’ve provided mind-blowing opportunities like the Student Prize for free. There needs to be more organizations and spaces like this and I’m glad that Aline was ahead of the game.

DL: I agree, so I will end by saying I am grateful to you for speaking with me, and I am grateful that Aline and Lenscratch brought us together!

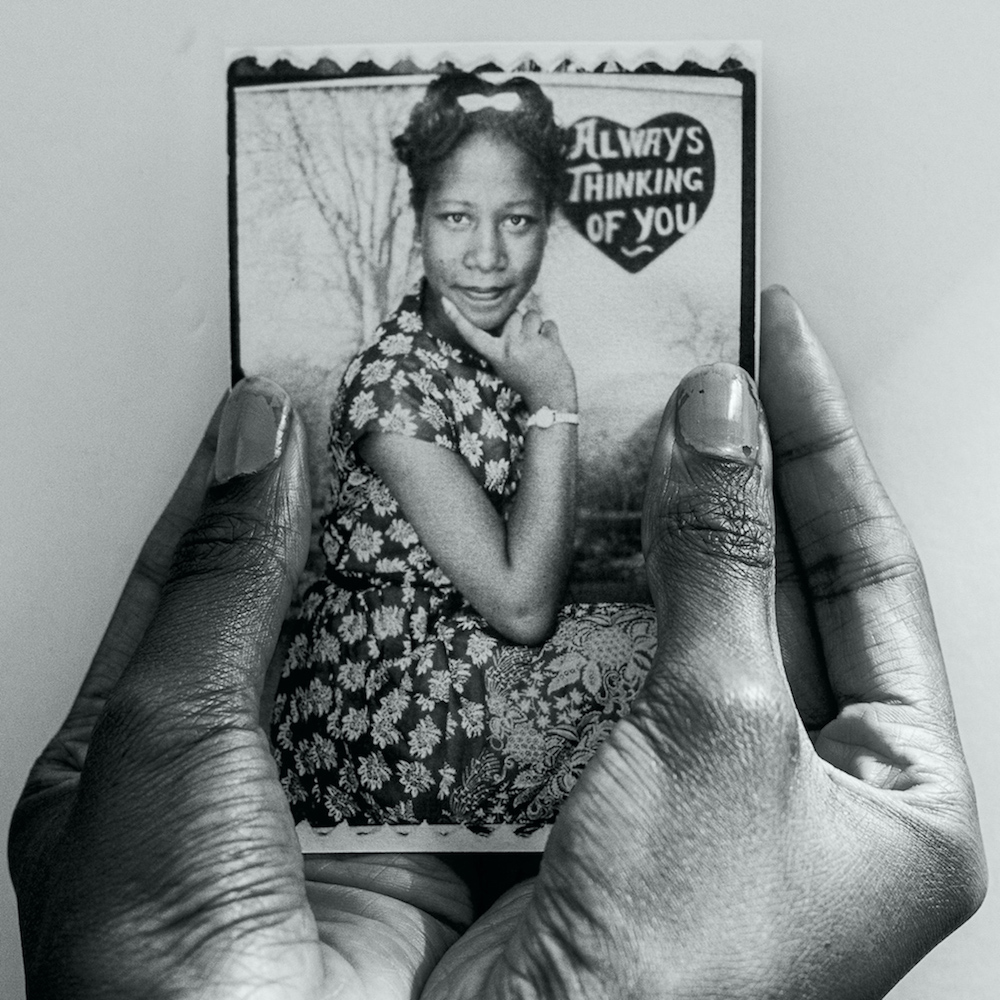

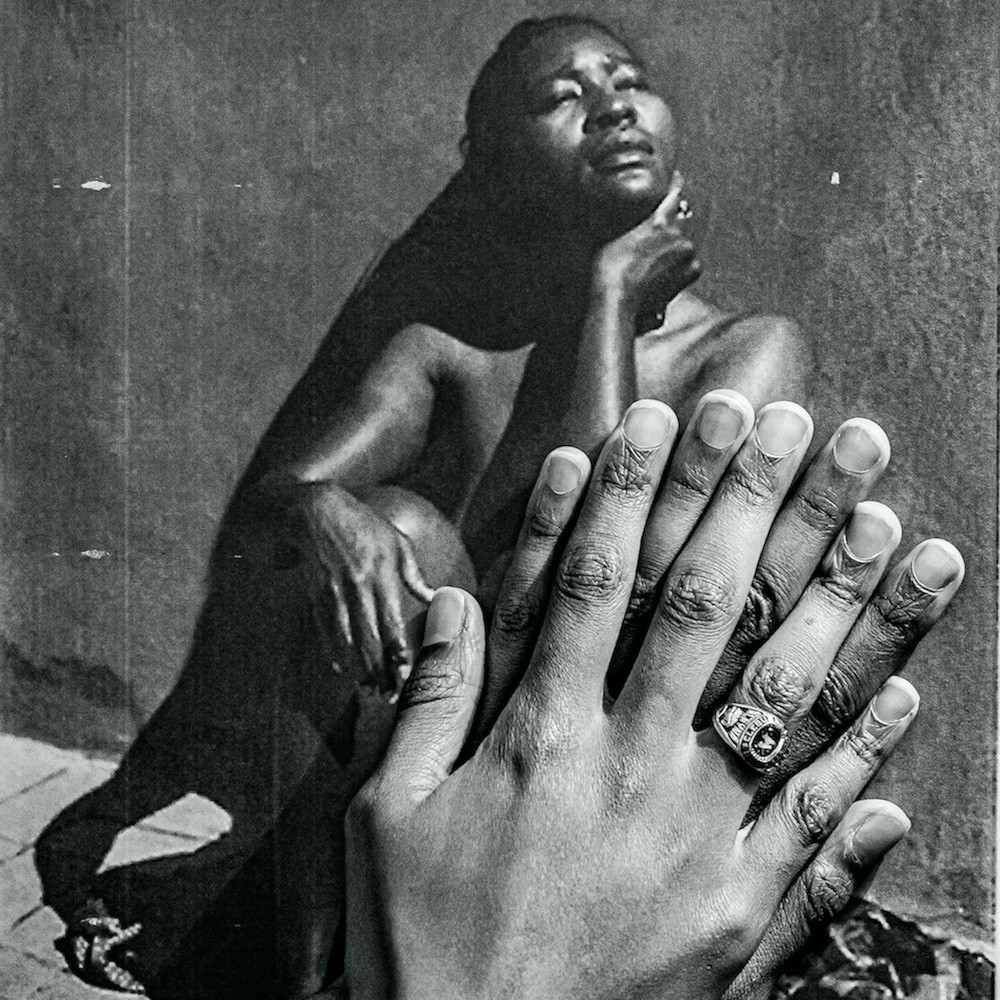

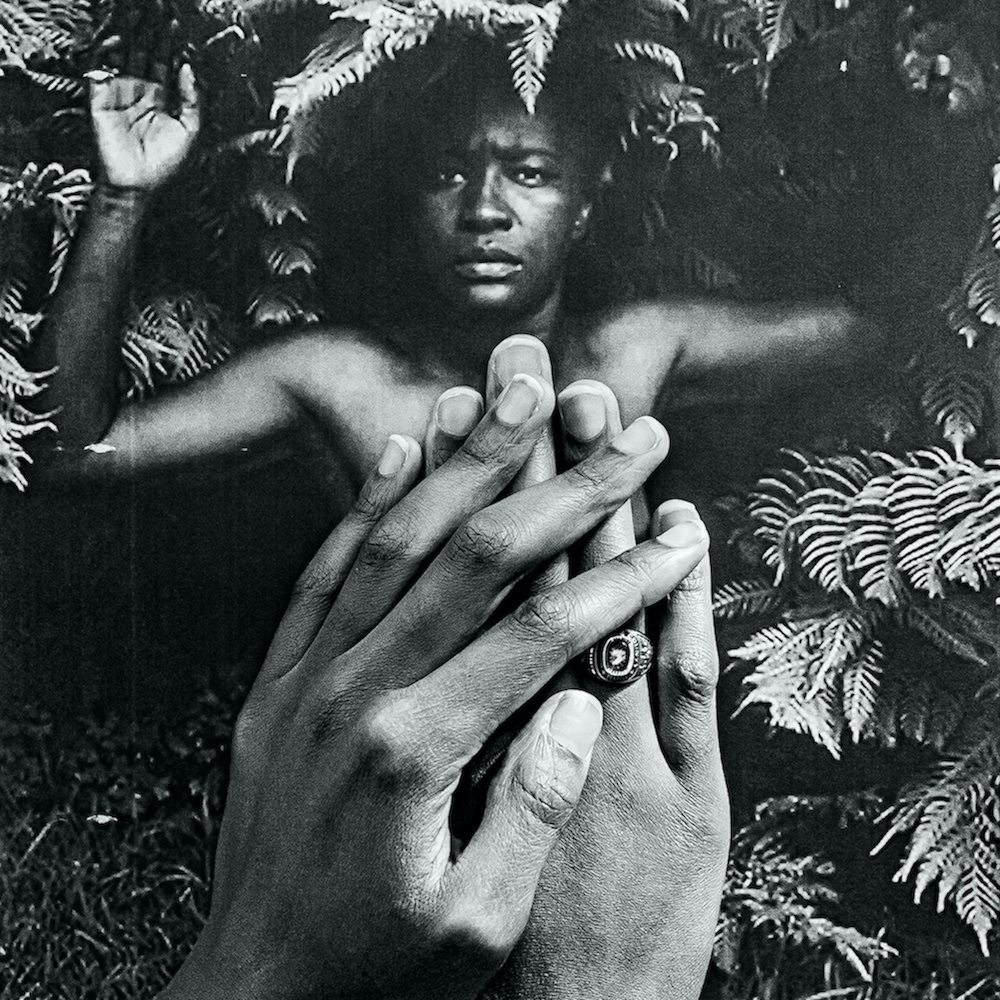

Alayna N. Pernell (b. 1996) is a visual artist, writer, and educator from Heflin, Alabama. She received her MFA in Photography from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in May 2021.Pernell’s practice examines the harsh realities and complexities experienced by Black American women and simultaneously creates space for productive dialogue by enacting an ethic of care, respect, and grace. Her work has been exhibited in various cities across the United States. Pernell was named the 2020-2021 recipient of the James Weinstein Memorial Award by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago Department of Photography, the 2021 Snider Prize recipient by the Museum of Contemporary Photography and a 2023 Mary L. Nohl Fellowship recipient. She was also recognized on the Silver Eye Center of Photography 2022 Silver List, Photolucida’s 2021 Critical Mass Top 50, 2021 Lenscratch Student Prize Honorable Mention, and more.

@alaynanpernell

Pernell will be sharing a Peek Behind the Curtain, hosted by Aline Smithson through the Center of Fine Art Photography on May 25th at 5pm MT, and will be teaching Archival Projects: Bringing the Past to Life at the Santa Fe Workshops, August 7 – 24, 2023.

Drew Leventhal is a photographer from Philadelphia. His work concerns borders, the haunting legacy of geography, and colonial history. Drew recently received his MFA in photography from the Rhode Island School of Design. He was the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize Winner and was a finalist for the 2023 Aperture Portfolio Prize.

@drew_leventhal

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: The Photobooth Technicians ProjectNovember 11th, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Rafael Hortala-Vallve: AUTOFOTONovember 10th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025