Redefining Historical Narratives Through Indigenous Perspectives.

Mural as part of the exhibition Garden for Boston at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. June 22 to October 12, 2021 * Bank of America Plaza on the Avenue of the Arts * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In honor of Indigenous Peoples’ Day 2023, LENSCRATCH sat down with Marina Tyquiengco, PhD, the inaugural Ellyn McColgan Associate Curator of Native American Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston to discuss the goals for the future of collecting Indigenous work, what she looks for as a curator regarding new acquisitions, and why Indigenous creators are so important in giving context to the existing collection. Tyquiengco is a CHamoru scholar of global Indigenous art with an emphasis on Indigenous Australian and North American works.

Marina Tyquiengco, Ellyn McColgan Assistant Curator of Native American Art at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. August 18, 2021 Native North American Gallery *Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Marina Tyquiengco is the inaugural Ellyn McColgan Associate Curator of Native American Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. A CHamoru scholar of global Indigenous art with an emphasis on Indigenous Australian and North American art, she has previously taught at Brown University. She has published articles in Feminist Studies and Lateral: Journal of the Cultural Studies Association as well as reviews for First American Art Magazine. She holds a PhD in Art History from the University of Pittsburgh.

View of Elizabeth James-Perry’s installation, Raven Reshapes Boston: A Native Corn Garden at the MFA, for the exhibition Garden for Boston, showing Appeal to the Great Spirit with corn and crushed shell border at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. June 22 to October 12, 2021 * Bank of America Plaza on the Avenue of the Arts * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Tell us a little bit about your background in the arts, and how you came to be the Ellyn McColgan Associate Curator of Native American Art at the MFA in Boston?

Art has always been important to me, and though I no longer make art, my family used to joke that I started drawing as soon as I could hold a crayon. I grew up first in Malessu’, Guåhan (Guam) where my father’s side has always lived. On the island, CHamoru language and culture was part of public education. Later, my family moved to Northern Virginia, and my family often went into D.C. to visit the museums. In high school, I took my first art history class and I realized that my passion for studying art exceeded my personal passion for creating art. My education at the University of Virginia and University of Pittsburgh were crucial in shaping me as an art historian and thinker, but learning about my own culture as a child and then having the privilege to visit many exhibitions growing up led me to pursue a curatorial path. I feel honored to be the inaugural associate curator of Native American art at the MFA in Boston. I began this role shortly after finishing my PhD, so I have turned that focused drive to learn and write to the MFA. What I bring to this role is a deep desire to better understand and communicate to the public the many histories of Native American art, rooted in Indigenous knowledges and my own understanding of myself as an Indigenous person and scholar.

Visitors at Elizabeth James-Perry’s installation, Raven Reshapes Boston: A Native Corn Garden at the MFA, for the exhibition Garden for Boston at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. June 22 to October 12, 2021 * Bank of America Plaza on the Avenue of the Arts * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, BostonYou have developed/created/curated many exhibitions over the course of the last several years, what have been some of the most memorable exhibitions, and what а some of the objectives in putting an exhibition together?

You have developed/created/curated many exhibitions over the course of the last several years, what have been some of the most memorable exhibitions, and what а some of the objectives in putting an exhibition together?

Garden for Boston (June 22-October 12, 2021) was an extremely impactful project for me to collaboratively curate with colleagues from the Department of Contemporary Art and Art of the Americas. It was composed of two installations, Raven Reshapes Boston: A Native Corn Garden at the MFA by Elizabeth James Perry (Aquinnah Wampanoag, born 1973) composed of a corn, beans, and squash garden, and the Radiant Community by Ekua Holmes (African American, born 1955), composed of a thousand sunflowers of many varieties. It also included two mostly photo-based murals collaboratively made by the artists. Both installations were creative responses to Cyrus Dallin’s Appeal to the Great Spirit, 1912, a sculpture meant to show support of Native peoples, but which has been difficult for many to encounter as it seems to set Native peoples in a mythic past. At the same time, Dallin’s sculpture, which stands on the MFA’s front lawn, remains an icon of the collection for many others. Responding to a bronze sculpture with two growing installations by women of color was poetic and incredibly thoughtful. Along with labels, my major contribution to the exhibition was co-organizing a series of conversations on intersections of Black and Native histories in Boston and beyond. It was mid-2021 and Zoom fatigue was widespread, but the three conversations between Black and Native scholars, knowledge holders and artists that we organized were very popular, with hundreds of sign-ups and attendees. There is a lot of knowledge held in this region outside of the museums and institutions. The popularity of these programs showed me that audiences want to understand and engage with relational histories that have not been learned.

I am currently working on the first of a two-part exhibition of contemporary prints, some of them photo-based, with Edward Saywell, the Chair of the Prints and Drawing Department, and our co-curator Duane Slick (Meskwaki/Ho-Chunk), who is an artist and a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design. Opening this November, the first exhibition, Marking Resilience: Indigenous North American Prints, celebrates the efforts to intentionally grow our collection of prints by First Nations and Native American artists.

There are multiple objectives when putting an exhibition together. I approach exhibitions as invitations to audiences to contemplate works of art and learn. I always seek to highlight the beauty and innovation of Indigenous works of art and demonstrate connections to continuing ways of making. I aim to provide useful context for visitors in an engaging and approachable tone.

View of Ekua Holmes’ installation, Radiant Community, for the exhibition Garden for Boston at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. June 22 to October 12, 2021 * Bank of America Plaza on the Avenue of the Arts * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Talk about some of the artists in your upcoming and most recent exhibitions and how they have helped the collection evolve?

Some of the most significant artists whose work I have displayed have been drawn from the MFA’s own collection. In April 2022, the MFA acquired Hanödagayas: Town Destroyer, a six-photograph suite by Mohawk artist Alan Michelson, who grew up in Boston. I have long admired Michelson’s thoughtful practice, which often highlights Indigenous history through lens-based installations and incorporates meaningful objects and sound. Hanödagayas: Town Destroyer presents six images that tell the story of the Clinton-Sullivan campaign.

Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer): Whirlwind Series Alan Michelson (American, born in 1953) 2022 Archival pigment print, printed using Epson P 20000 printer * Edwin E. Jack Fund * © Alan Michelson * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

As the Ellyn McColgan Associate Curator of Native American Art at the MFA in Boston, what аre some of your personal goals for the future of the collection that you curate and manage?

Before I started, there was already an effort by other colleagues in Art of the Americas to incorporate Native American art into displays around the museum. Since I started in September 2021, I have been working to incorporate more Native American art thoughtfully and appropriately throughout the Art of Americas Wing as well as in other colleagues’ exhibitions and gallery rotations. I have been working to rethink our collection displays to incorporate more Indigenous perspectives. A longer-term goal is rethinking the Native North American Gallery. In addition to the curatorial work, I am working to build and strengthen relationships between the MFA and our local Native communities.

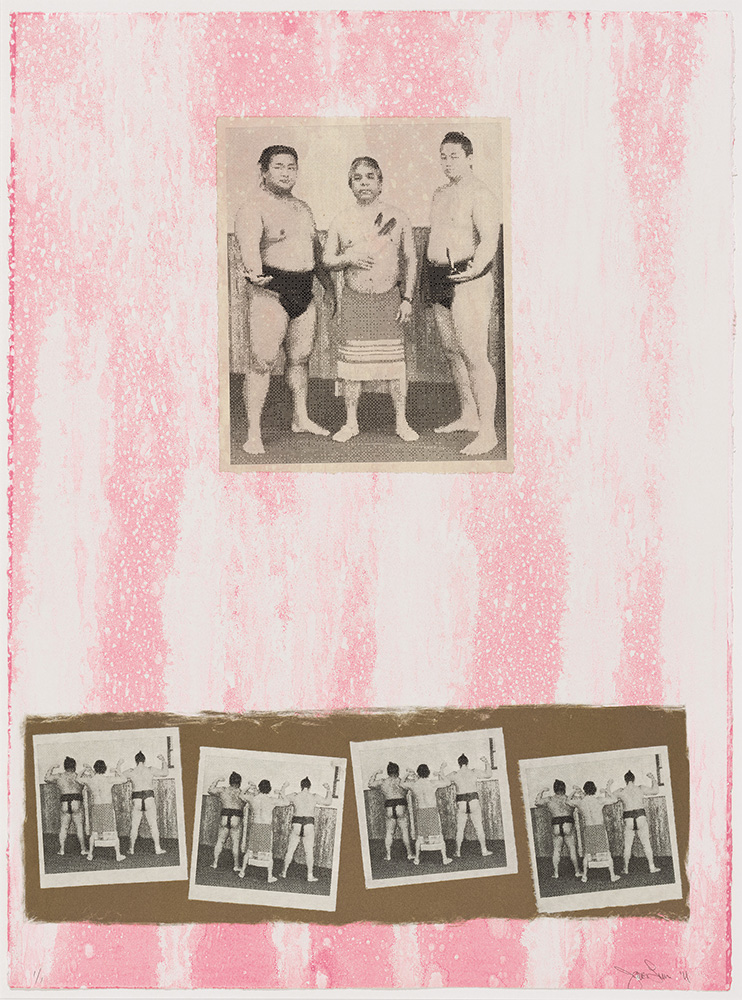

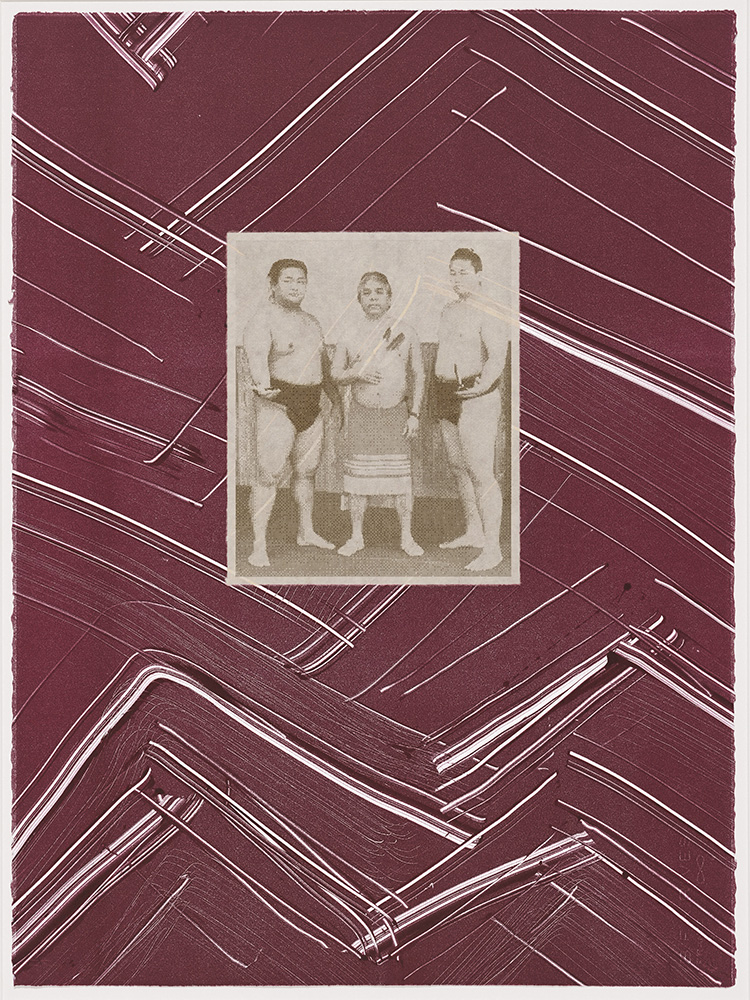

Sumojazz (13) James Luna (1950 – 2018) 2011 Monotype * Lee M. Friedman Fund * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

When you аre looking to add work to the permanent collection of Native American Art for the MFA Boston, what аre you looking for?

This is a great question! In general, curators begin with assessing their own collections, understanding first what is under their care and what is well represented. Curators often acquire works to fill gaps and strengthen particular areas of the collection—for example, collecting a piece from an artist unrepresented in the collection, but whose community is well represented. I am also looking for works that provide different views of histories that are already told through the collection. For example, I am in the process of collecting some works of art by Wabanaki makers, as our collection includes many fine paintings of Dawnland.

Sumojazz (3) James Luna (1950 – 2018) 2011 Monotype * Lee M. Friedman Fund * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Why аre Indigenous creators so important in giving context to the existing collection of American Arts at the MFA Boston?

The Native American collection at the MFA started in 1877, quite early in the history of the Museum, but there was not a gallery dedicated to Native American art until 2010. Although 2010 seems late and is, this gallery was among the first of such spaces found in museums across the country.

The history of Boston is deeply embedded in the history of the United States and central to that history is encounters with Native peoples. Our foundational myths as a nation are nearly 250 years old; Indigenous understandings of this place are immensely older. Contemporary Indigenous creators, especially those creating lens-based art, can provide new context for histories we think we understand. Historical Indigenous creators allow us to better understand the world of making at particular time and place. Art has tremendous cultural meaning, and it’s crucial for us to tell more complete narratives of American art and to celebrate Indigenous ways of making.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: The Photobooth Technicians ProjectNovember 11th, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Rafael Hortala-Vallve: AUTOFOTONovember 10th, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025