Photographers on Photographers: Julia Schlosser on Hyewon Keum

For the entire month of August, photographers will be interviewing photographers–image makers who have inspired them, who they are curious about, whose work has impacted them in some way. I am so grateful to all the participants for their efforts, talents, and time. -Aline Smithson

Korean artist Hyewon Keum’s work concerns monumental depictions of the urban environment. Hyewon is drawn to hidden, in-between spaces, to places that underpin, facilitate and support the functioning of society at large but which often remain underground, inaccessible or concealed. In her body of work entitled Cloud Shadow Spirit, the artist turns her eye to the burgeoning animal death care industry in Korea, Japan and the US. Hyewon examines pet cemeteries, columbaria, crematories and mourning facilities, as well as the practice of preserving animal bodies by freeze-dry taxidermy or by turning animal cremains into “memorial stones.” Vivian Sming, artist and creator of Sming Sming Books, an artist run publishing studio based in California, first introduced me to Hyewon’s work. It was Vivian who originally suggested that I interview Hyewon. I was able to curate Hyewon’s work into the exhibition Remembering Animals: Rituals, Artifacts and Narratives, 2018. Hyewon’s work influenced me personally when I had the opportunity to photograph my own pet’s cremation. Her haunting images gave me permission to look at what I might otherwise have turned away from.

Cloud Shadow Spirit was supported by Parkgeonhi foundation and Artsonje Center.

Julia Schlosser, MA, MFA, is a Los Angeles based artist, art historian, and educator. Her artwork elucidates the multilayered relationships formed between people and their pets. Her writing and research interests focus on contemporary photographic artwork that depicts animals’ lives and deaths. She curated the exhibition Remembering Animals: Rituals, Artifacts and Narratives, 2018, and chaired the 2017 inaugural Seeing with Animals Conference. She is a lecturer at California State University, Northridge and Citrus College where she teaches photography and the history of photography.

Julia Schlosser, MA, MFA, is a Los Angeles based artist, art historian, and educator. Her artwork elucidates the multilayered relationships formed between people and their pets. Her writing and research interests focus on contemporary photographic artwork that depicts animals’ lives and deaths. She curated the exhibition Remembering Animals: Rituals, Artifacts and Narratives, 2018, and chaired the 2017 inaugural Seeing with Animals Conference. She is a lecturer at California State University, Northridge and Citrus College where she teaches photography and the history of photography.

Hyewon Keum is an artist based in Seoul, Korea. Her photography work encompasses the observation and interpretation of modern life in urban spaces and underlying social phenomena. Her solo exhibitions have been featured at Artsonje Center and Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea. Her works have also been exhibited throughout Korea and internationally, including at Seoul Museum of Art, The Museum of Photography Seoul, Lishui Art Museum, Pyeong Chang Biennale, Nanjing International Art Festival and Seoul Photo Festival. Keum is the winner of the 12th Daum Prize from The Parkgeonhi Foundation of Culture. Her works are part of the permanent collections of The Museum of Photography Seoul, Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul Museum of Art, National Museum of Contemporary Art (Art Bank) and The Jeju Museum of Art.

Cloud Shadow Spirit

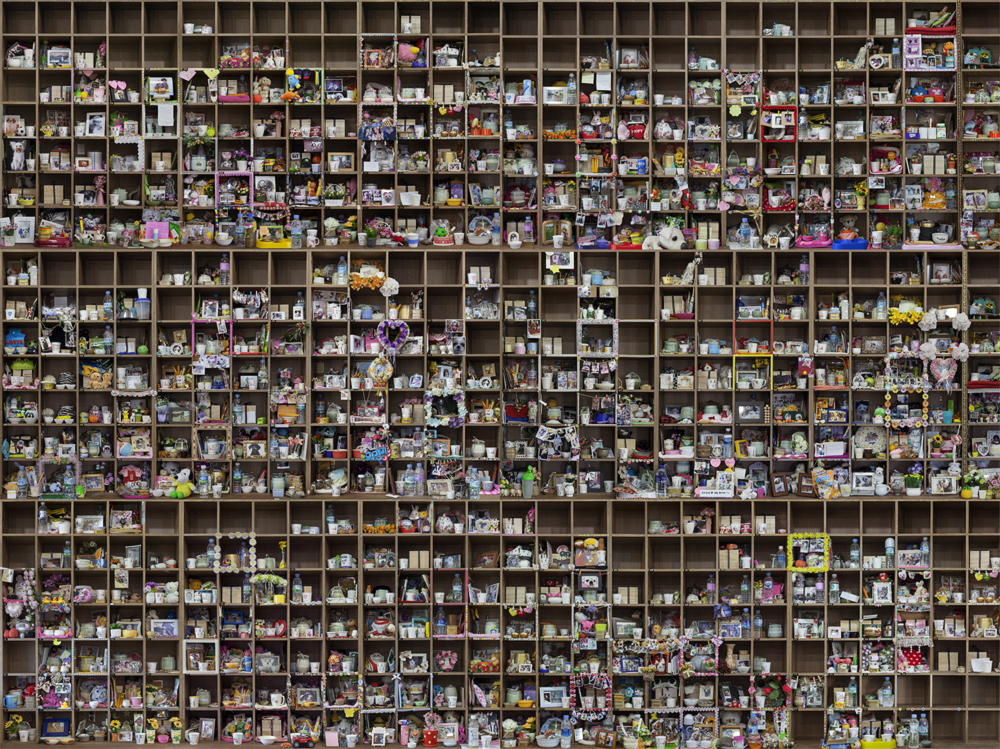

My photographic series, Cloud Shadow Spirit, showcases various societal attitudes toward the death of companion animals. I have traveled to Korea, Japan and the United States, shooting photographic images of funeral rites for animals, animal crematories, pet cemeteries, pet columbaria, memorial stones (which are also called ‘angel stones,’ a recent trend in the market), and stuffed companion animals. Both the United States and Japan have their own history of funerals for animals that reaches back almost 120 years. I also chose these two countries because of their significant influence on the funerary culture in Korea, as well as for their diversity and specificity of funeral for animals. Alongside the two countries, I observed Korea, as it has a short history of animal funerals yet is experiencing a rapid growth of demand for such funerals. The sites of processing the deaths of companion animal, attitudes and ways of commemorating the dead, and the wide variation of types of such places and activities are recorded in the process.

The realm of death is usually separated from the realm of life. That attitude is well displayed in commemorating the deceased in spaces such as cemeteries or columbariums. However, people sometimes keep death within the territory of their lives by having taxidermists preserve their pet to place where they will be encountered in their ordinary lives, or by having memorial stones produced to carry around with them.

As I have been observing and recording the special bond between people and their companions, I intend to highlight the ways that such relationships may reveal the solitary quality of life in modern society. I believe contemporary culture of funeral rites for companion animals is not a subject that is solely related to personal loss and grief but is an issue that should be examined through a comprehensive and sociological perspective. – Hyewon Keum

Julia Schlosser: Can you talk about your decision to photograph companion animal funeral culture in your series Cloud Shadow Spirit?

Hyewon Keum: The motivation for this project is based more on the experiences of people around me than from my own personal knowledge. When I was about to start the research for this project, it so happened that a group of my friends all had to let go of their beloved dogs at around the same time. I had several friends who were surprised by the sudden death of their dogs, and others who were preparing for the imminent mortality of a sick or elderly animal. One of my friends even embarrassed me by comparing the loss of her dog to the loss of my father. This does not mean that I do not consider the death of animals to be a serious issue. However, that conversation raised a fundamental question for me about the relationship between humans and companion animals, a question about the emotional environment of our contemporary lives.

JS: In your statement about your series Cloud, Shadow, Spirit you mention both the extreme emotion felt by grieving pet owners and the economic explosion surrounding the rapidly expanding pet memorialization industry. Can you speak more about how your photographs comment on the dichotomy between the personal emotions of the pet owners and their actions as consumers?

HK: As the photographs show, the rituals and formalities surrounding animal funerals reflect a condensed version of that of human funerals. These days, companion animals are often chosen as family members, are raised like humans and then die in a similar manner. As I witnessed people mourning for the loss of their companion animals, and holding funerals and memorial ceremonies as if they were losing a child, I could tell how much they relied on these relationships and how much comfort they received from them. This is a very human process for letting go of an animal that accompanied them for so long.

However, issues of dominance and possession complicate our relationships with animals. For many, a relationship with a companion animal presupposes an intimate relationship, which rivals that of another family member. However, animals are bought and sold and are not given the same societal rights and agency as are people. How do the financial decisions and funerary choices that a person makes for their companion animal reflect their relationship with and attitudes toward that animal?

My photographs embody various– often conflicting and ambivalent social attitudes– toward the death of companion animals in the societies in which I have photographed. Although a single photograph may not reveal the many contradictory attitudes held by a society toward the animals under its care, a series of photographs depicting various rituals and aspects of the material culture of death further elucidates the range of societal attitudes toward death and human-companion animal relationships.

JS: Hilda Kean suggests that animal cemeteries are “places…in which human and animal are blurred in various ways.” Can you talk about the ways that human and non-human animals overlap in the spaces you have photographed in Cloud, Shadow, Spirit?

HK: In fact, there are cases where animals and humans are buried together at the animal cemetery. However, beyond this simple fact, my attention was on the cemetery as a place imbued with significations about the roles and desired relationships that the humans project onto their pets. Especially, the names of the companion animals on the tombstones and the epitaphs written like a description of a human life seemed to be a point of coexistence and overlap of humans and humanized animals.

JS: What was your process in deciding to photograph spaces of mourning when they are empty of the (human) inhabitants who come to grieve or mourn?

HK: I’ve been interested in the man-made formalities per se of mourning. Even though no humans are present in the photographs, I think that places for mourning and forms of memorials speak sufficiently about the people who use these spaces. And if there had been people in my photographs, the focus of the meaning would have shifted a bit. I wanted to let the audience confront the subjects for themselves, giving them space to read and interpret the images in their own ways.

JS: Your photographs of taxidermied animals feel very different than the more formally composed images of cemeteries and columbaria from the series. Rachel Poliquin refers to taxidermied pets as “an unsettling fusion of animal form and human longing,” and reminds us that unlike other forms of remembrance for individuals who have died, taxidermied animals “are the departed.” (emphasis hers) Was your experience photographing the taxidermied pets different than the other photographs in this series?

HK: Some pet owners choose to preserve the appearance of their companion animals forever by performing a freeze-dry taxidermy procedure on the animal’s body after death. In this case, the funerary practices concerning animal bodies deviate from those regarding humans. Main-stream funerary conventions for human beings in Korea, Japan and the United States do not usually provide for the long-term viewing of preserved human bodies. In fact, the process of freeze-dry taxidermy is typically performed only on animal bodies. I am interested in discovering what this dichotomy reveals about the nature of the relationship between companion animals and their owners.

Freeze-dry taxidermied animals signify a commercialized as well as an objectified death. Taxidermied animals from the Still Life series have become still objects that will never vanish. What’s more, although dead, they still look alive. In this way, taxidermied animals resemble photographs. Consider how taking a photograph of an object is one means to appease the regret of losing that object. Similarly, the desire to taxidermy an animal is derived from the desire to hold on to the animal like one can hold on to the tangible photograph. It is important here to note that this is only possible since the object in question is an animal, not a human being. Whether the impetus to taxidermy a pet is based on the fear of loneliness and loss or whether it is based merely on personal taste, a taxidermied person would appear terrifying while a taxidemied animal can look like a lovely, cute doll. I did not photograph the stuffed animals with their owners or set in a realistic scene. This is because my intention was to have the audience confront the animals as frozen images, and to create portraits of objectified companion animals.

JS: Did your own relationship with animals or companion animals influence your choice of subject matter or the decisions that you made for this project?

HK: I had a pet when I was little. Back then, it was common to have cats to catch a mouse or dogs to look after the house, but animals were not kept simply as pets. Of course, there were those who protected and loved animals but pets fell short of being given the position of “companion.” Although the culture of companion animals in Korea did not evolve as long ago as it did in Japan, the U.S. and Europe, Korea has recently witnessing a rapid increase in related industries and markets that deal with the culture of companion animals. The motive for the outset of this project is more from such changes in the air and related influences than from my personal experience.

JS: Are you continuing to work on this series or have you moved on to another photographic project? Can you tell us what you are working on currently?

HK: As an extension of this project, I have photographed the keepsakes of various companion animals after their deaths and interviewed their owners. Although the series is not yet complete, the process of compiling primary source material and observing this funeral culture through an ethnographic lens has influenced and changed my attitude toward the work since I first started making these photographs.

I am currently working on a new project based on my grandmother’s personal history. it is intended to discover individuals, especially women, who have been excluded or unrecorded in modern history.

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Olga Fried: Intangible EncountersFebruary 18th, 2026

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026