Jaulas // Cages: Steffanie Padilla

In a show of solidarity for those who are being held captive against their will, oppressed, and colonized by this authoritarian regime “Jaulas // Cages” is a week celebrating emerging Latinx Image-makers who I am interviewing to gain their insight and voice on the current danger it is to be outside the white patriarchal standard the current US government is striving for. This week is dedicated to all immigrants, and to those who do work or are currently in a cage. A cage being anything from physical, emotional, mental. These “Jaulas” are struggles we ALL have been within at points in our life: An enclosure of gender, a cage of identity, the pens of oppression, a box to be tokenized by.

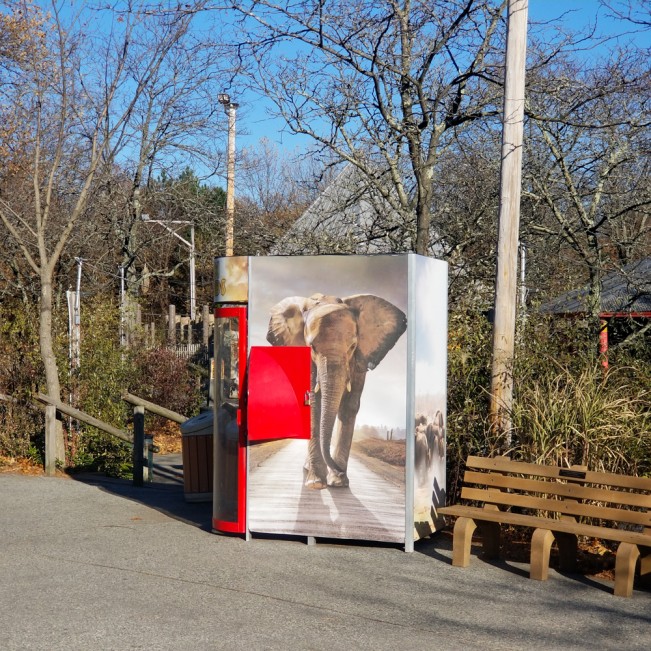

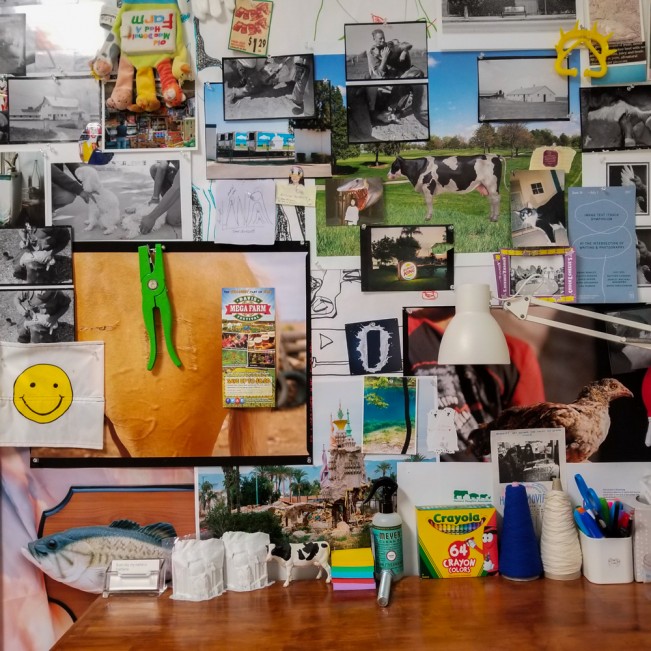

steffanie a. padilla (b.1989) is a méxican-american conceptual artist based in providence, rI and is a current mfa photography 21’ candidate at rhode island school of design. her research interest focuses on examining the human/nonhuman animal relation within media studies, popular culture, and technology. steffanie’s work uses: video, sound, analog film, found objects, 3D forms, and the archive—as a way to question and better understand how nature and animals reveal their plight against human apathy and fantasy.

When you hear the word Jaulas//Cages, what are you thinking of?

Birds. Caged parakeet birds to be exact. As a kid I grew up seeing swap meet vendors selling all kinds of birds in cages, sometimes rabbits and chicks too. Certainly I wouldn’t think of humans in cages. Although, that is the kind of gruesome reality we’re facing in places like detention centers here in the U.S. There is one photo I have seen that has stayed with me throughout the years that shows the immigration system in its dehumanizing light. The caption reads: “A boy from Honduras watches a movie at a detention facility run by U.S. Customs and Border Protection on September 8, 2014 in McAllen, Texas. The Border Patrol opened the holding center to temporarily children after tens of thousands of families and unaccompanied minors from Central America crossed the border to seek asylum in the United States during the spring and summer. Migrants refer to the facility as ‘la perrera’, or dog kennel, because of its cage-like fencing.” Photo by John Moore can be seen here: (https://www.luciefoundation.org/programs/the-story-behind-the-image/)

How would you describe your upbringing and how you came to be an artist?

I would describe it as american in the sense that I consumed copious amounts of television and fast-food. I had a very loving and supportive upbringing, the question of how I came to be an artist is perhaps not so clear. I think I have always had this fascination with wanting to be surrounded by things that made me want to believe in magic. Things like: computers, lava lamps, glitter, music videos, cartoons, video games, toys, mood rings, glow in the dark stickers, magazines, holographic cards, gifs and CD’s. I found all to be wildly intriguing and still do to this day. Part of being an artist I think is the ability to see the world in an entirely new way, which may involve a lot of unlearning, reflexivity, and sensibility. After studying photography for some time, I think I came to be an artist when an image was no longer an image but rather this two-way communication surface that acts seemingly neutral and definitive. Or when my favorite computer game or animatronic became a machine running on circuits and 1’s and 0’s. Basically I came to be an artist when my world crumbled and now I am carefully rebuilding it.

From your upbringing and work, what does Latinidad, mean to you? Does being Latinx inform your work?

While being born and raised in Southern California in a predominately latin neighborhood, I wouldn’t exactly know what Latinidad means to me other than a sense of community. Despite my overall work not being explicitly informed by being Latinx (other than a project I worked on about my mother’s hometown in Chihuahua, México) I do think this part of me will always be an underlying layer that lives within the work in some form or another.

Who and/or what inspires you?

People who persist in asking questions because they truly want to understand and have a sense of urgency. Recently that has been Bell Hooks and artists James Bridle and Olafur Eliason. Also, author Richard Louv and Dr. Kate Darling who is a leading expert in robot ethics at MIT. All remarkable thinkers and researchers.

The work you make challenges the viewer to reflect on our consumption: food, media, space. When do you think you started to reflect and challenge the human-centric viewpoint we are conditioned to cling to?

I think my growing concern over our physical and conceptual separation with the natural world was fueled by two films, Earthlings (2005) and Samsara (2011). The two films provide a sober look into how complex systems work by documenting scenes either done through an aerial perspective or hidden camera. When opaque systems such as immigration, agriculture, or the internet function at a magnitude scale that is difficult to comprehend, they become harder to think about and change. My hope is that we find solutions to overcome digital noise and feelings of apathy and continue to exercise our critical thinking muscles because our future depends on it.

What do you want to see more of in the art world?

I would like to see more work that deals with interrogating how we’ve come to understand certain sets of knowledge by virtue of media, especially with animals, and if that may say anything about our current understanding of the climate crisis. To the second part of the question, I don’t think the art world necessarily wishes to cage artists as in to control them. I think it depends, but I do think it can happen, especially once one starts working with larger institutions.

What advice would you have for up and coming Latinx artists?

I would say this applies to anyone regardless of where you are from or how you identify. Try to understand your history in whatever form that may be. What has your culture taught you? What has your environment taught you? Why do you think it is important to make the work you’re doing now in the year 2020? Keep asking questions and then ask some more. Listen and feel within.

What is next for you?

Something that hopefully involves not looking at a screen (zoom fatigued) and being with nature.

Thanks for having me!

*All images in this feature were taken with a phone. To see the work please visit www.steffaniepadilla.com

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Salua Ares: Absense as FormNovember 29th, 2025

-

Ricardo Miguel Hernández: When the memory turns to dust and Beyond PainNovember 28th, 2025

-

Pamela Landau Connolly: Columbus DriveNovember 26th, 2025

-

KELIY ANDERSON-STALEY: Wilderness No longer at the Edge of ThingsNovember 19th, 2025

-

Jackie Mulder: Thought TrailsNovember 18th, 2025