Deborah Orloff: Elusive Memory: Lost Histories

This week, we will be exploring projects that use the found photograph. Today, we’ll be looking at Deborah Orloff’s series Elusive Memory: Lost Histories.

One of my friends in graduate school introduced me to the work of Deborah Orloff . I was immediately enamored with how she brings new life to photographs that have been harmed in some way. She is able to embrace the flaws and show a deeper intimacy of the images at hand.

One of my favorite pastimes is going to antique and second-hand stores. Anytime I see a found photograph, I not only have so many questions but I also think about Deborah’s work. In an antique store with others’ family photos, we think about the personal history they hold and how they ended up here – were they discarded? Sold after an estate sale? Are people and events in the photographs even remembered by anyone alive today? There are many places we can go with these questions and Deborah addresses them intimately through Elusive Memory: Lost Histories.

Deborah Orloff is a photo-based artist and Professor of Art at the University of Toledo. Originally from New York City, Orloff received her MFA from Syracuse University and her BFA from Clark University. Although her primary medium is photography, she has also worked in video and installation. Her artwork has been included in numerous exhibitions at national and international venues including: the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, The Museum of Fine Arts in Nizhny Tagil, Russia, and the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh, Scotland. Orloff’s current project, Elusive Memory, was selected by the Museum of Contemporary Photography as part of their Midwest Photographers Project and received sponsorship from Hahnemühle Paper. Orloff has been the recipient of dozens of grants and awards including the Ohio Arts Council’s 2019 Individual Excellence Award and most recently, the Arts Commission’s 2022 Merit Award. Her newest work, Elusive Memory: Lost Histories explores the relationship between photography and memory while evoking the universal experience of struggling to recall the past. The images allude to lost family histories – particularly as they relate to forced migration (the case for her ancestors who fled Russian pogroms) – and speak to the ephemeral nature of memory.

Elusive Memory: Lost Histories

We know that memories are inextricably linked to photographs, but what happens when we lose access to our family photos and the histories associated with them? Like many Jewish Americans, searching for my family’s roots has led to myriad dead ends; I’ve found names, dates, and random facts related to a handful of ancestors, but nothing close to a complete narrative. Details of individuals have been lost as people die and their memories disappear with them. This is further complicated by the fact that I come from a diasporic culture where most official records from Russia and Eastern Europe cease to exist, and histories depend on oral traditions.

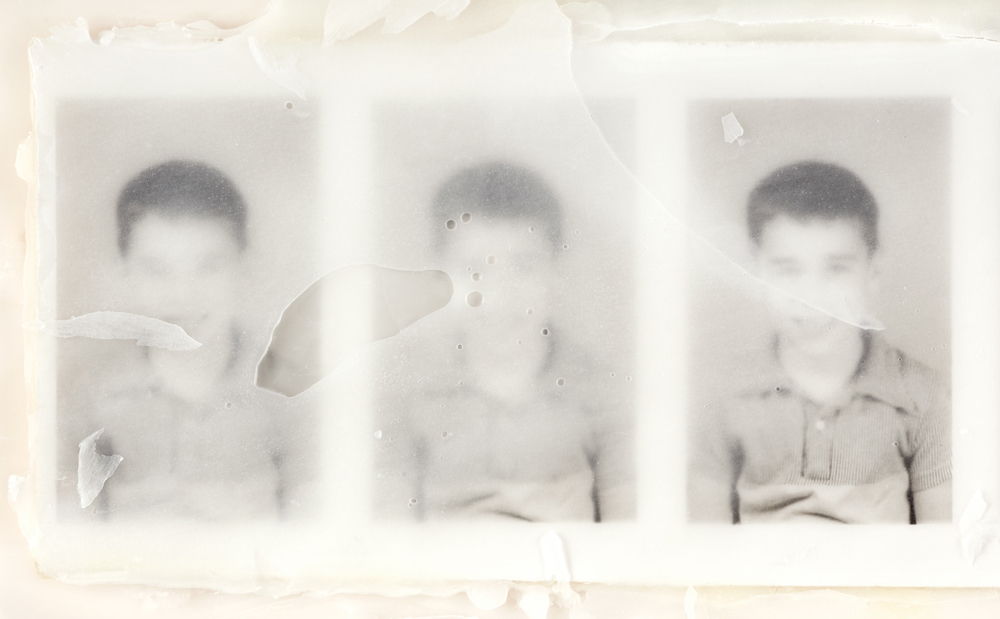

Elusive Memory: Lost Histories is a series of intimate photographs that deny viewers much of the visual information photography normally reveals. The images allude to lost cultures, stories, and identities – especially in situations of forced migration (as was the case for my ancestors who fled Ukraine during Russian pogroms). My photographs represent the universal experience of struggling to recall details of the past – often with little clarity. In their final presentation, banal objects remind us of lost family histories and speak to the ephemeral nature of memory.

Epiphany Knedler: How did your work come about?

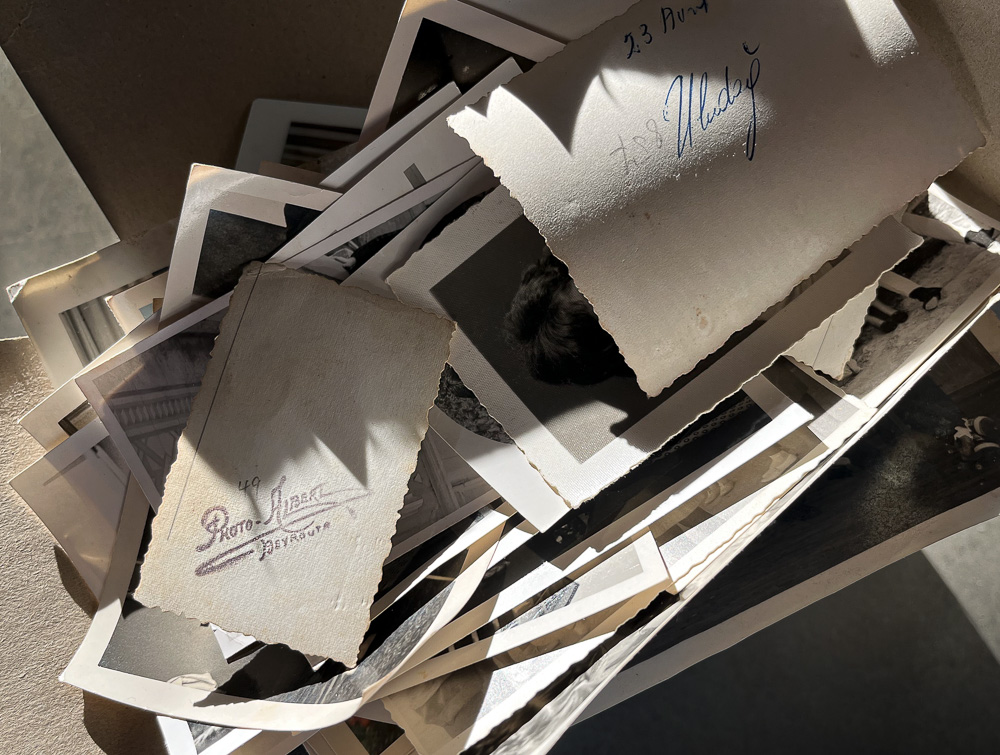

Deborah Orloff: Elusive Memory, is a long-term project that explores the complicated relationship between photography and memory. I started thinking about this connection after my father died unexpectedly; as I was writing his eulogy, and recalling memories to draw upon, I was picturing each memory as a still photograph. I realized I couldn’t distinguish my memories from the photographs I was recalling, and I started to wonder if I really remembered specific moments and people or if I’d just seen the photographs so many times, I’d fabricated memories. I knew I wanted to make work about this phenomenon, but I didn’t know what form it would take until 10 years ago when they were selling my dad’s house. Cleaning it out we discovered cartons of old photographs that had been damaged from years of flooding in the basement. It wasn’t until I started photographing individual objects and enlarging them significantly that I saw them as a visual representation of the way we remember (and misremember) with their disrupted imagery and missing content. That’s when I realized what the project would be.

EK: Do you manipulate the images in any way? Why or why not?

DO: Every photograph is a manipulation of reality. When we choose what to include and exclude, how to frame the subject matter, how to light it, where to focus, and how much depth of field to use, we manipulate the subject. In this sense, I am manipulating the photograph – but less so in post-production where I am making subtle adjustments to what is already there.

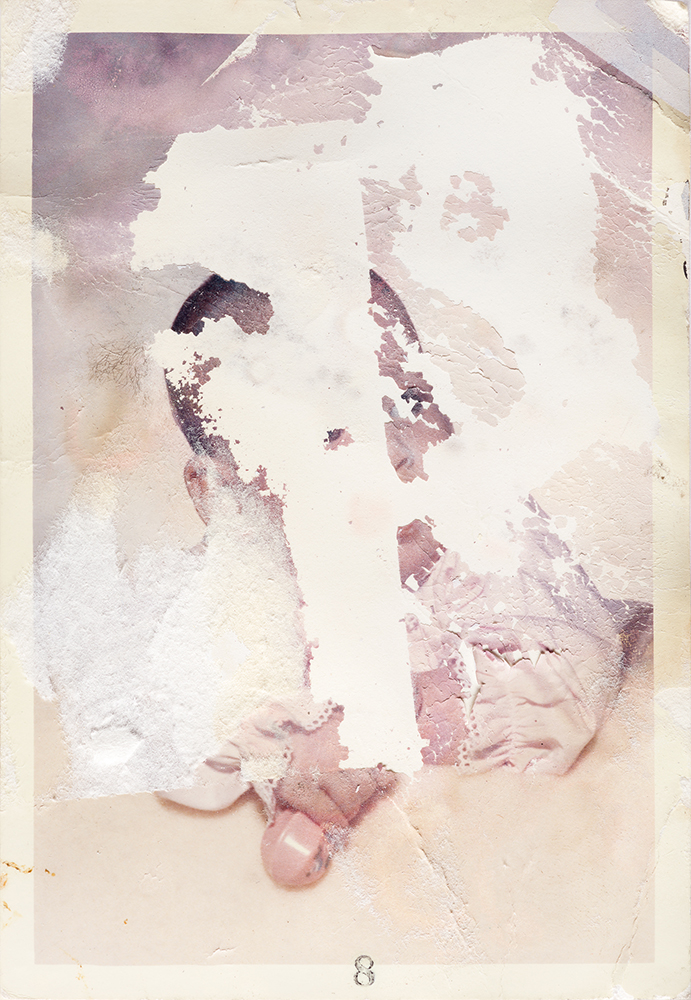

In the large-scale images from 2013-2019, I present the photographs as uniformly sharp prints (about 30×42”) to emphasize every surface texture and detail from the water damage. Rather than scanning the images (which tends to flatten them out), I use studio lighting to create a trompe l’oeil effect, so the textures (only visible in the enlargements) look three dimensional and the viewer feels like they are in the presence of an intriguing object, rather than a photograph of an artifact.

Conversely, in my new, smaller-scale work, I’m intentionally making it difficult for people to see the details of my subject matter. This strategy may seem antithetical to photography, but my recent pieces are about the things we can’t see or know. So, I’m manipulating what’s in front of my lens by using shallow depth of field, layering objects on top of each other, and turning over photographs to deny viewers most of the visual information that was physically in front of my camera.

EK: Can you tell me about your artistic practice?

DO: Personal experiences are usually the impetus for a project but I’m always interested in finding a universal aspect of that experience in my artwork. I tend to let ideas simmer for a long time before I act on them. Something has to “click” for the momentum to begin. With Elusive Memory, it was seeing the damaged photographs enlarged on my 27” monitor. Once I have a sense of my concept, I start playing. At first, I just start putting things in front of the camera and experimenting to see how I can best communicate the idea. You have to make a lot of bad photos to get a few good ones!

In the beginning of Elusive Memory, I was photographing the damaged pictures exactly as I found them (though not always in their entirety) on a copy stand with studio lighting. In some case prints were stuck together and I loved the idea of hidden pictures and what that could represent. Then I started taking liberties with the subject matter and creating my own (physically) layered images, hiding identities and other details. By 2020 I was actively trying to communicate what it feels like when you’re trying to remember something but can’t quite see it. This led me to create an installation (In Search of Memory) with 25 small, faded photographs floating on the wall – some of which you can barely see. That led me to make relatively small (7×10 – 16×20”) photographs with shallow depth of field to allude to the people and stories we can’t remember and the experience of struggling to recall details of the past. The project is still evolving and Elusive Memory: Lost Histories has become an extension of the original project. I’ve started incorporating non-photographic objects (such as letters, boxes, and cultural artifacts of deceased relatives) into my latest pieces.

I also do research – whether it’s reading about memory, theory, or diving into my family history – it’s an important part of my practice. I’ve been thinking a lot about family histories and how much of my own family history has been lost as older generations die and their memories disappear with them. Much of Jewish history and culture has been passed down through oral traditions and so much of our collective history is lost and unknown. Throughout the course of the project, I’ve been trying to learn about my ancestors, but I quickly found out that little information exists beyond my grandparents. I knew I had ancestors from Russia but, until recently, that’s all I knew. As I investigated Jewish history more generally, I understood why family records are so hard to find; Jews have been persecuted and essentially “on the run” for millennia. Jewish Americans can’t typically trace our ancestry back very far because records have been lost or destroyed. I discovered that my great, great grandparents lived in the “Pale of Settlement” (now Western Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Lithuania and Poland). By the 1880s, it was the only place Russian Jews were allowed to live and it essentially became a large ghetto that Russian Jews were forced into from other areas. Antisemitism and Pogroms eventually pushed out Jewish families who fled to Europe, Israel, and the US in the late 19th and early 20th century. My ancestors were part of that mass exodus. This research became important for me both personally and in my new work.

EK: What’s your relationship to the found photo? How do you come up with the stories or meanings with these images?

DO: I have always been fascinated by vernacular photography – especially old photos – but when I started photographing my family’s damaged photos, I became much more aware of their nuances and their physicality. For example, family photos from different time periods have unique characteristics: Polaroids have a certain look and sometimes still have the “pull tab” attached (you can see this in “53 Pontiac” and “the Pencil”); for many years photographs were printed with borders; photographs from the 1960s often had dates stamped on the border; prints from the early and mid-20th Century sometimes had decorative borders or scalloped edges. Then of course there are the clothing and hairstyles that place them in a specific era. I’ve always been interested in these signifiers and seeing the changes in people’s appearance over time.

As much as I love digital photography, it has practically negated the physicality of family photos. Until recently, snapshots were always printed. They were objects people held in their hands. They were placed in wallets, albums, and frames. The artifacts were precious and they were made sparingly -usually marking significant moments like life cycle events – unlike now when people take photos of every aspect of their lives constantly; the single image no longer has the same significance; it’s just part of a scroll on social media (if it’s seen at all).

Found objects also have a history. Take “Baby Portrait” for example. A baby was photographed in a commercial studio. The proud parents printed a 5×7 for the mantel and dozens of wallet size prints that were distributed to family and friends. Mom kept a small print in her wallet which became worn around the edges and was later replaced by more recent pictures. The wallet photo ended up in a drawer, then a box. The box lived on a shelf but soon ends up on the floor, and eventually in the basement where it was abandoned and neglected. Heat, humidity, and water transformed the print and now, under the scrutiny of my lens, the cracked emulsion looks like peeling paint and the baby is unrecognizable.

In my newest work, I’m including passport photos, ID cards, and other elements that suggest travel and migration. I’m seeing these documents through the lens of forced migration and antisemitism. So, when I find (and photograph) an old identification card that belonged to someone who likely immigrated around the time the card was made, I can’t help wondering about their experience, and seeing the image as being layered with the suggestion of categorizing and dehumanizing people. Suddenly the picture on an innocuous ID card looks like a criminal mugshot and conveys otherness and undesirability. The document in “Photo Identification,” reminds me of a prison mugshot with the height markings behind the man and the prominent number in the foreground. For me, it turns him into a number and conjures up images of the Holocaust and lines of immigrants being “processed” at Ellis Island. Even the embossments over faces and staples through photographs feel like a violation of the subject. I have a visceral response to these found photos; they give me chills.

Of course, my interpretation of the images is only one of many possible readings. The objects I’m photographing have gravitas. Whether they are 30×42 and uniformly sharp, or 11×14 with minimal depth of field, I want them to have a commanding presence, so people consider and perhaps imbue them with their own meaning and experiences. I’m happy to share what I’m thinking but never want to tell people how to read an image; rather, I see my work as an invitation for dialogue.

Epiphany Knedler is an imagemaker sharing stories of American life. Using Midwestern aesthetics, she creates images and installations exploring histories. She is based in Aberdeen, South Dakota serving as an Adjunct Instructor and freelancer. Her work has been exhibited with Lenscratch, Dek Unu Arts, F-Stop Magazine, and Photolucida Critical Mass. She is the co-founder of MidwestNice Art.

Follow Epiphany Knedler on Instagram: @epiphanysk

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Juan OrrantiaDecember 19th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The PorchApril 28th, 2025

-

Matthew Cronin: DwellingApril 9th, 2025