Toni Pepe in Conversation with Douglas Breault

It is nearly impossible to view the artwork of Toni Pepe and not see your own maternal figures mirrored in the images. The further you get from being a child the more you begin to see the caretakers in your life as real people outside of their role as your caregiver, opening up a complicated set of feelings to understand them as individualized people. You begin to understand the decisions and actions of their lives differently when you see them beyond this role. Pepe illustrates a potent and emotional intimacy in her work that focuses on children and mothers to describe the passage of time. The spirit of photography is rooted in holding tightly onto an instant in time, and Pepe’s exploration in photography is not solely a first account of motherhood, but rather an attempt to untangle the inescapable fears all people share in understanding the intersection of life and death through beauty and contemplation.

©Toni Pepe, from the series Second Moment I

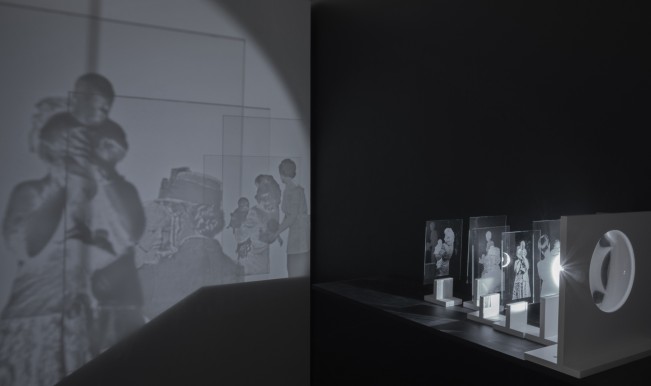

I first recall seeing Toni Pepe’s images in the series “Second Moment 1”, which embraces seemingly floating figures of mother and child in a deep Caravaggio-esque depth of black negative space. The beauty in the images is tinged with a foreboding element of fear, as the maternal forms attempt to balance and contain a baby in erratic waves of water. The scenes are reminiscent of a dream, or potentially a nightmare, where you are desperately attempting to maintain a grip on a precariously flailing baby against the elements. The images are steeped with a tenderness of touch contrasted with a necessary strain in the arms and legs of the mother in order to maintain poise. Pepe understands the paradox of caretaking and the ambiguity of safety, both in reality and within our own psyche.

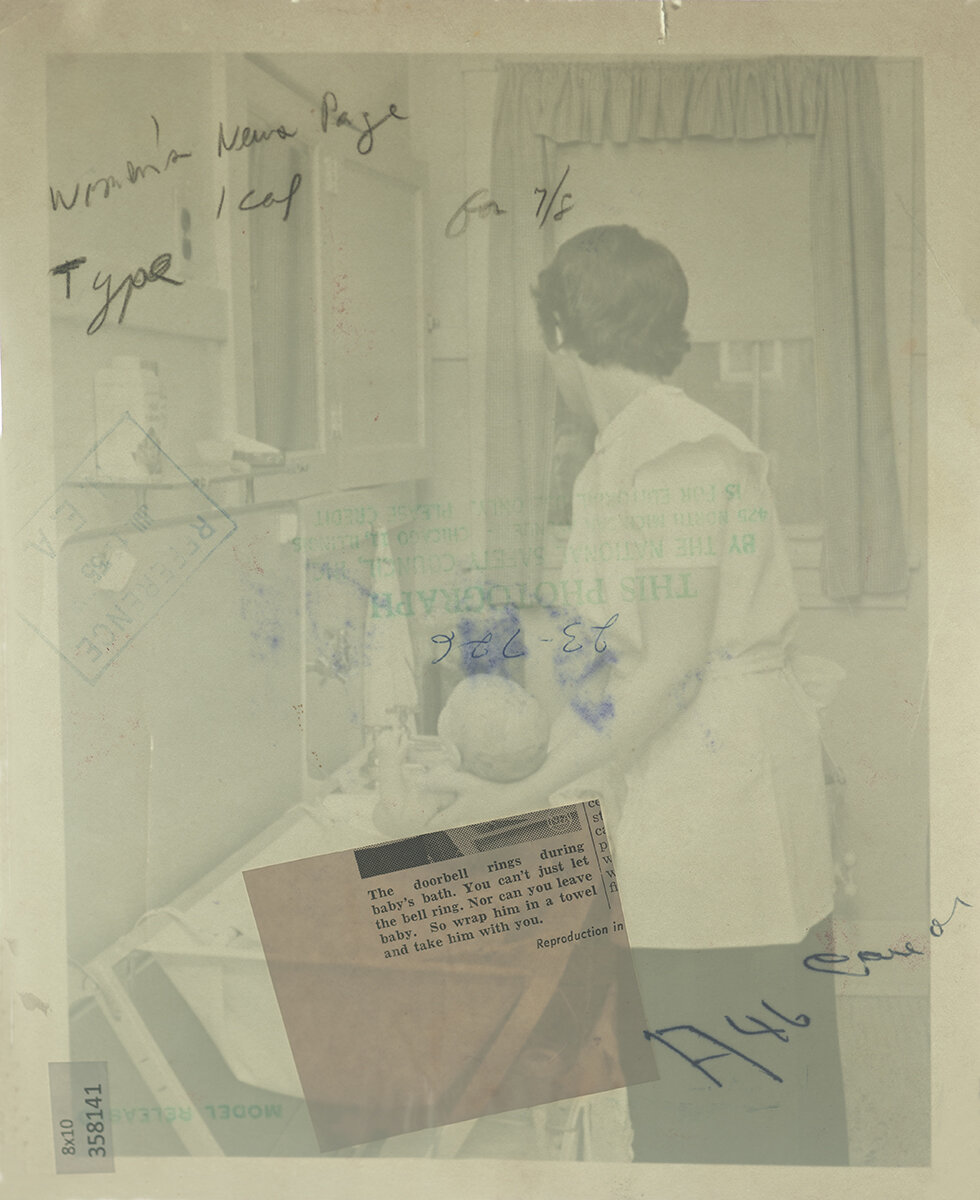

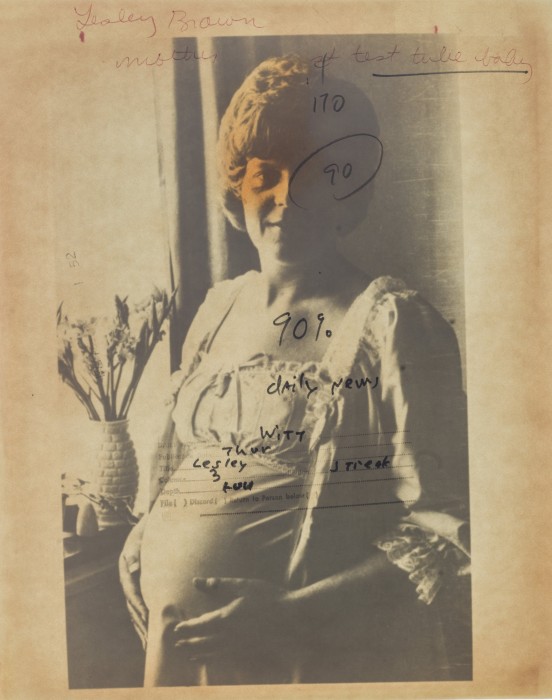

The everyday use of photography is related directly to memory – holding onto celebrations, accomplishments, and milestones as a relic of evidence and truth. A photograph can serve as a reminder of a life lived, and often the value of that photograph is not realized until that life is lost. While Pepe’s work is rendered from an account as a mother, her work instigates an appreciation of beauty in human intimacy. In the series “Mothercraft“, I return to the tender feelings of being small and protected by the embrace of my mother. The fragmented handwriting in the archival images reminded me how familiar I am with my own mother’s handwriting, and how special that individualized notation can be. Pepe touches upon the balance of love and longing and the ambiguity of safety and comfort. In an increasingly digitized world, Pepe encourages the viewer to spend time on the tactility of photography and its potential to crack open a myriad of ideas and questions being present despite the elusive flow of time.

Much of your work is a thoughtful investigation into the role of being a mother in the United States, and through the perspective of yourself being a mother. How have maternal figures in your life or your own memories of being a child influenced your understanding and portrayal of motherhood?

My work has always been informed by personal experience, but I tend to reference and articulate those experiences through a wider lens. In other words, while I use myself and my children in photographs, we are reenacting an archetype and performing the character of mother and child for the camera, as opposed to a more cinema veritas approach. I also use other people’s family albums and press imagery to create a throughline from the particular to the universal. My goal as an artist is not necessarily autobiographical, instead, I want to create a sense of the macro view of the world or the political implications of the everyday gestures of caretaking. Also, first-hand accounts from mothers are few and far between. It’s important for me to distinguish a mother’s-perspective in my work from my own childhood memories.

A recurring theme in your work is the tension between birth and death. What types of symbols or concepts do you enlist to illustrate that precarious line between life and death in your work?

I’ve been exploring the idea of mothers as givers of life and death in my own work for several years now. This notion comes from the writer Samantha Hunt, who upends the sentimental versions of motherhood by integrating the sobering idea of death. There are many ways in which birth and death intertwine. They are events that should exist on opposite ends of a pole but echo a certain kind of commonality in their mystery and significance. In becoming a mother, I had to face my own mortality and my children in ways I never did before. I became much more aware of the r line between life and death and that the joys of parenting are not exempt from this encroaching darkness.

I use a variety of materials and visual techniques to point toward the relationship between birth and death. I work mainly with photographic materials from the 20th century because this is the period in which the practices surrounding birth and death moved from the home under the management of women to the hospital where it became professionalized by mostly male doctors. In addition, during the mid-20th century, the paternal voice of the doctor is introduced via figures like Dr. Spoke and Dr. Sears. The snapshot and press photographs found in my work are also suggestive of our fear of death. The photograph is supposed to be a static, legacy of our lives and collective history. The photograph, however, has never been static. Its physical qualities are in constant flux (photographs fade, crease, stain, etc.) and their meanings shift over time, depending on who is doing the looking and under what circumstances.

Your photographs in Second Moment I and Second Moment II are documented performances with babies and toddlers. What do you think now when you look back on those photographs since your children are older? Do you have ideas for how your work will change as your children become older?

I am fascinated by time and the futile attempts to structure, distort, or forget about it. Much of my work is about the perception of time as seen through the lens of motherhood. The daily rituals give shape to time and provide a comforting sense of purpose. Also, the incremental changes that happen to the body often go unseen day to day, but when viewed from a distance, maybe 6 months or a year, the growth becomes more apparent. The feeding and sleep schedules that morph into school calendars and pick-ups/drop-offs, create a rhythm for time and a form that fluctuates in tandem with the development of the body.

I look forward to my work changing as my children (and myself) age. I will continue to observe the unfixed, ephemeral nature of time and its relationship to the physical and specifically photography. My process is directly inspired by literature and Annie Ernaux’s memoir, The Years is informing what I’m making right now. Ernaux skillfully illustrates the inconsistencies of time – it’s expansion and contraction or the way it can flash in front of our eyes or unfurl in front of us as a seemingly endless path. She also ties the perception of time to photography, memory, and the body in a way that I hope to convey in my own work.

What do you hope your work communicates about you for future generations of artists and mothers?

I hold my work closely and put a tremendous amount of pressure on it when it’s in my studio and I’m making my way through it. After it leaves, however, I tend to let go and hand it off to the audience. I understand that I have my intentions as an artist, they certainly inform what I am making and how I am making it, but once the viewer is in front of the piece, I can only hope that the work encourages them to question their perception of time, history, memory, and their relationship with photography. I want my work to unsettle and dislocate a viewer’s understanding of caretaking and reveal connections for viewers that may go unseen. I am not comfortable with mother artist labeling; it feels too limiting and exclusive and runs counter to my attempt to widen the scope of caretaking and offer a more expansive narrative that presents the complicated and layered experience of care far beyond the Madonna and child archetype.

Toni Pepe is a Boston-based artist whose creative practice is grounded in photographic processes, memory, storytelling, and identity, as seen through a feminist lens. Found photographs from both private and public collections play a crucial role in her practice. Pepe often uses vernacular or press imagery to explore alternative notions of an archive as well as different modes for collecting and preserving knowledge. Pepe enjoys finding the possibilities and limitations of photography – how it can make us both remember and forget, make something feel entirely present and absent, and show us something beyond the frame. She views the medium of photography as a tool amongst many that she uses in the studio. Occasionally, the camera is the answer to her creative question, but oftentimes, she is using other techniques including mold-making, assemblage, embroidery, performance, and laser etching. As Pepe weaves these varied processes into her practice, her focus is always turned toward how these materials relate to photography in an expanded sense.

Pepe is currently chair and assistant professor of photography at Boston University where she has helped to build and now launch a new MFA in Print Media and Photography. She received her MFA from the Rochester Institute of Technology and an MLA in visual culture from Boston University. Pepe has exhibited both nationally and internationally including at the Center for Photography at Woodstock and the Wege durch das Land, Music & Literary Festival. She was a finalist for the Massachusetts Cultural Council Fellowship, a Critical Mass top 50, a Review Santa Fe 100, an SPE Imagemaker, and an Artist Trust Grant awardee. Her work is in the permanent collections at the Danforth Art Museum, Candela Books & Gallery, the Magenta Foundation, as well as many private collections. A solo exhibition of her work is now on view at the Danforth Art Museum through January 29, 2023.

Follow Toni Pepe on Instagram: @toni.pepe

Douglas Breault is an interdisciplinary artist who overlaps elements of photography, painting, sculpture, and video to merge spaces both real and imagined. His work has been collected, published, and exhibited nationally and internationally, including at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the Czong Institute for Contemporary Art (South Korea), Space Place Gallery (Russia), the Bristol Art Museum, the Rochester Museum of Fine Arts, Amos Eno Gallery, and VSOP Projects. Breault has been an artist in residence at MassMoca and AS220 and was awarded the Montague Travel Grant to study in London and Paris in 2017. Douglas is a professor of art at Babson College and Bridgewater State University, and he has been a guest critic at MassArt, Wellesley College, Kansas City Art Institute, and the Slade College of Art, among others. Douglas is the Exhibitions Director at Gallery 263 in Cambridge, MA. He received his MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University and a BA in Studio Art from Bridgewater State University, and he currently divides his time between Boston, MA, and Providence, RI.

Follow Douglas Breault on Instagram @dug_bro

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Richard Koenig: Field Notes: View from a Hotel WindowFebruary 13th, 2026

-

Beyond the Photograph: Editioning Photographic WorkJanuary 24th, 2026

-

The Next Generation and the Future of PhotographyDecember 31st, 2025

-

Spotlight on the Photographic Arts Council Los AngelesNovember 23rd, 2025

-

100 Years of the Photobooth: Celebrating Vintage Analog PhotoboothsNovember 12th, 2025