Daniel Kariko: Impermanence: Environmental Collapse of Louisiana’s Vanishing Coast

This week, we will be exploring projects inspired by place. Today, we’ll be looking at Daniel Kariko’s series Impermanence: Environmental Collapse of Louisiana’s Vanishing Coast.

I found Daniel Kariko’s work while I was applying for graduate school. I resonated with his explorations of place through time and imagery. I am so fortunate to have worked with Daniel and to watch his process and practice grow. While Daniel was my instructor, he largely balanced work between Louisiana and bugs – the bugs he could work on at home in North Carolina, while the Louisiana work was a long-term (often summer) project. During the school year, people were constantly coming down to the Photography Studio with new bugs they’d found, and the fridge was always stocked and waiting for their close-up. If he wasn’t photographing bugs, he could be found scanning film from the Deep South. Both projects stemmed from his love of place.

Daniel captures the objective truth of his subjects. Impermanence: Environmental Collapse of Louisiana’s Vanishing Coast is now a twenty-three-year-long project that continues to grow. He effectively merges concepts of time, the Anthropocene, and documentation through formal landscape portraits. In his images, viewers can see the dedication and love Daniel has for the practice of photography.

Daniel Kariko is a North Carolina based artist, and a Professor of Fine Art Photography in School of Arts and Design at East Carolina University, in Greenville, North Carolina.

Kariko’s images investigate environmental and political aspects of landscape, use of land and cultural interpretation of inhabited space. He worked on several long-term photographic projects in his native Serbia, recording the aftermath of the war in Balkans. Since 1999 Kariko documented the endangered wetlands and dramatic changes in the landscape in Barataria- Terrebonne region of South Louisiana.

Kariko’s work has been shown nationally and internationally in galleries and museums, including: Noorderlicht Photofestival, Groeningen, The Netherlands; Yixian International Photography Festival, Huangshan City, China; Manchester Science Festival, UK; Rewak Gallery, University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates; Edinburgh International Science Festival, UK; Museum of Contemporary Art of Vojvodina, Novi Sad, Serbia; Rijeka Foto Festival, Croatia; Fries Museum, The Netherlands; Festival della Scienza di Verona, Italy; Photon Gallery, Vienna, Austria; Royal Albert Hall, London, UK; ArtCell Gallery, Cambridge, UK; Galata Museo del Mare, Genova, Italy; Orlando Museum of Art, Orlando, FL; and The National Museum of Nuclear Science and History, Albuquerque, NM.

Kariko’s work was featured in a number of online and printed publications, including: Communication Arts, Nature, Art Papers, CNN Photos, National Geographic Proof, PetaPixel, Wired, Design Observer, and Discover Magazine.

Kariko received his Masters of Fine Arts from Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona in studio arts with a concentration in photography.

Follow Daniel on Instagram at: @danielkariko

Impermanence: Environmental Collapse of Louisiana’s Vanishing Coast

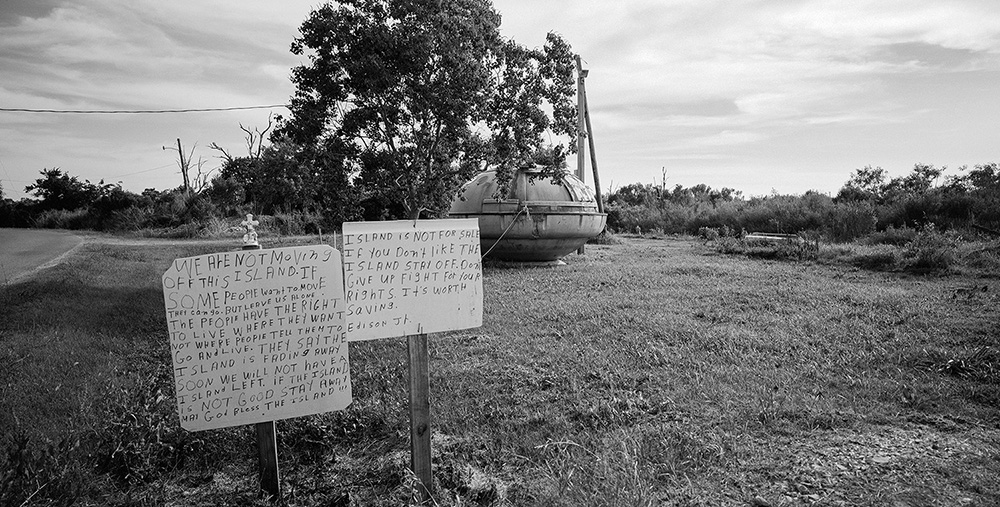

Louisiana is at the forefront of global sea level change, experiencing the highest rate of coastal erosion in America, losing about one hundred yards of land every thirty minutes- land loss the size of a football field every half-hour. In addition to global sea level rise, in this century alone, a dozen major storms, including Katrina and Rita in 2005, and Ida in 2022, drastically changed the geography of Louisiana’s coast.

People of Louisiana are closely defined by the landscape they inhabit. Unfortunately, this fascinating correlation between people and geography is under a dire threat of vanishing simply because the land they occupy is physically retreating. Our modern technology and engineering is capable of physically slowing the coastal erosion, but it is not very good at preserving the cultural heritage. Many of South Louisiana’s coastal inhabitants, including Indigenous Americans, Cajuns, and Asian Americans are affected by loss of natural resources, economic impact, and direct loss of property. Every year, many small local communities are abandoned and gradually sink into the wetlands.

These images are a recent selection of a long-term investigation of rapid changes in wetlands geography and population in Southern Louisiana, largely due to human activity. The photographs are results of more than two decades of annual revisitation of the specific geographic area, The Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary. Witnessing this physical unraveling of landscape became a personal visual metaphor for the disintegration of my native country of Yugoslavia.

The global environmental concerns that place Louisiana in center of world’s attention make this project timely in its relevance. It is the longest undertaking of my career so far, chronicling the continuous shifting of the landscape and adaptation of humanity to our new, warmer and wetter world.

Epiphany Knedler: How did your project come about?

Daniel Kariko: My project started as an annual darkroom photography/ coastal ecology workshop in Louisiana wetlands in 2000. My former photography professor, Dennis Sipiorski and his biology colleague Dr. Gary LaFleur were interested in taking students to Barataria- Terrebonne National Estuary. The idea was a collaboration between arts and sciences from the get-go, and it was successfully run for a decade and a half. Since then, I’ve continued my annual trip to Louisiana to revisit the same locations, and people.

EK: What relationship does place or location play within your practice?

DK: The specific locations within this project serve as markers of change. I don’t try to replicate the photograph from the same angle, but use the locations of cemeteries, trees, or buildings as anchors to the continuing story of the geological change. In my other projects, the relationship with the location is less exact, however, no less important. For my first seventeen years, I grew up in former Yugoslavia, now northern Serbia. I observe the landscape through a prism of an immigrant. I investigate societal and/or environmental connection to a location, more or less, in all of my projects.

EK: I know time has played a big role in this series; is that something you initially knew or was it a reaction as you spent more time with the project?

DK: There is a repeating joke (or perhaps not a joke) with my closest friends and collaborators on the project- We always say: “This is probably the last time we photograph this place.” And so it goes from year to year, for the past ten years at least. Every time we feel there is a logical conclusion to the effort, something significant happens. The most recent event was Hurricane Ida in 2021. It was extremely destructive to the area’s people and geography. So, I felt that I had to continue…

The project originally started as an examination of the threatened coastline, and over the years became a chronicle of a location that is extremely important to nation’s infrastructure, and culture to the people who inhabit it. It grew more important with every annual trip back to the wetlands. While I did not realize that time would play such an important role in the series, it organically became one of the unique aspects of the work. I also realized that physical disappearance of Louisiana’s coastline became a personal metaphor for dissolution of my native Yugoslavia.

EK: I understand a lot of this project started with pinhole Polaroids but have since switched to digital; can you elaborate on that decision?

DK: The project morphed through several photo and video process versions over the years. I originally photographed it in 35mm BW film. The decision to switch to 4X5 pinhole and shoot it with Polaroid Type 55 film happened in 2006, my first trip after Hurricane Katrina. I wanted to be able to develop film at the location and use longer exposures. This was out of practical reasons, but also because I wanted ALL the physical and chemical processes to occur at the place of the origin of the images. Another nod to the connection with the landscape. I was photographing the disappearing location with the disappearing process.

I eventually had to conclude the Polaroid chapter of the project, because my supply of film ran out. I may go back to photographing with my pinhole camera again, in the future.

By 2015 I switched to using a medium format 6X12cm panoramic camera. I started to enjoy composing the images of that very flat landscape with a format that would emphasize the horizon.

EK: What’s next for you?

DK: Hard to tell. I would like to eventually produce a book of this work, but I still enjoy returning to the Louisiana coast and creating new images, now, 23 years into the project. Perhaps I need a quarter century perspective of the effort. I always have at least two other projects going simultaneously. I enjoy long-term dedication to places.

Epiphany Knedler is an imagemaker sharing stories of American life. Using Midwestern aesthetics, she creates images and installations exploring histories. She is based in Aberdeen, South Dakota serving as a Lecturer of Art and freelance writer. Her work has been exhibited with Lenscratch, Dek Unu Arts, F-Stop Magazine, and Photolucida Critical Mass. She is the co-founder of MidwestNice Art.

Follow Epiphany Knedler on Instagram: @epiphanysk

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anna Guseva: The Black Night Calls My NameJanuary 26th, 2026

-

Nathan Bolton in Conversation with Douglas BreaultJanuary 3rd, 2026

-

Jake Corcoran in Conversation With Douglas BreaultAugust 10th, 2025

-

Matthew Cronin: DwellingApril 9th, 2025

-

Jordan Gale: Long Distance DrunkFebruary 13th, 2025