Interview with Kate Greene: Photographing What Is Unseen

I first met Kate Greene as a visiting artist in one of my final critiques of undergrad. We later reconnected the following year once I moved to the midcoast of Maine, where I got to know her and her work better.

She’s so eloquent with her words and I’m always fascinated when I have the opportunity to hear her talk about work, especially her own. Her approach to image-making feels so methodical and deliberate in every choice she makes. I really enjoyed the conversation we had, and the opportunity to learn more about her practice.

Can you talk a little bit about your background before coming to photography? Especially if dance has played any role in shaping your practice.

I was a dancer from pretty early on until my early 20s. Studying dance formally at Emerson College in Boston when I was 18 until I was about 21. However, I ended up studying abroad and had the opportunity to study in Holland for half a year. That was kind of a game changer for me because I didn’t take any dance classes there. I took all art history and writing classes, and so I had a sort of visual art boot camp that semester. We were so spoiled by studying the “thing” and then being able to go see the “thing” while in Amsterdam.

And so, I started to really think about the language of visual art in a serious way and the advantages of being able to communicate through a visual language symbolically. I was studying a lot of Dutch still life paintings which have this whole symbolic language to them, and it sort of blew my mind. I was like, “What? How could these flowers actually be a conversation about death and mortality?” I didn’t understand… So there was something really impactful about that moment for me, seeing those paintings which are so hyper-descriptive, they almost look like photographs.

And so when I got back to Boston, I had a really hard time transitioning back into the dance studio. I felt like I was a different person, and at the time, I decided to leave school and briefly moved to Los Angeles. I worked a stupid job at a management firm in Beverly Hills, I was a receptionist for a firm that represented huge celebrities, and I was so nauseated by it. I hung up on Brad Pitt *laughs* which was like the biggest no no, and how you get fired as a receptionist in LA.

The vapidness of that drove me towards seeking other things that I could engage with and brought me back to that headspace from when I was in Holland. So I would go to the Getty Museum a lot, which was free and felt like another world. It’s like a spaceship from the future, the museum is insane, and they have an incredible photo collection. Which was the first time I had seen Diane Arbus’s work, and it just kinda cracked something open for me. I never really understood that a camera through a specific eye could crack things open in such a different way. For me, before it was “the machine that everybody had” and it just recorded the world, I didn’t understand that it could be that powerful.

So that disrupted things for me, I started photographing a lot… Or maybe destabilized things for me *laughs* and so I decided to go back to Boston and finish school. For a while, I just didn’t know what I wanted to do. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to go back to Emerson, so I took some classes at New England School of Photography, and then I was advised to apply to MassArt. Then I did, and everything kind of changed.

Sorry that was really long-winded… but that was sort of my trajectory *laughs* life crisis then move to LA… I’ve done that twice by the way *laughs*

But yeah, it wasn’t a straightforward path, and I don’t totally know if there’s a one-to-one from being a dancer to being a photographer. Certainly, there was knowing who I am as an artist in the world, but not knowing how to do that early on.

And, in terms of your development as a photographer, what was the timeline like for your different modes of making and finding cohesion between them?

I think early on at MassArt I found the view camera and that was a tool that really clicked things into place for me.

I was studying with some really incredible landscape photographers, like Barbara Bosworth and Laura McPhee, but then also studied with Abe Morell, who has a more experimental approach, and so, I feel like that’s where I built up my technical chops and learned how to make pictures. For my thesis project at MassArt, I was really interested in this landscape in Central Massachusetts that had this sordid history, where girls had a history of disappearing. And so I was making landscape photographs in those locations and also making portraits of young women in the area.

It was the kind of project where I felt like I had reached a moment with the way I was making pictures that could only take the work so far. So, I decided it would be a good moment to apply to grad school since I wanted to push the picture-making in new directions.

I already knew what I was interested in. I’ve always been obsessed with this idea of the persistence of the past in relation to place, so that was a part of my work really early on, and it’s still a driving force behind it. When I went to grad school I sort of let the content go for two years and just experimented with new ways of making pictures. That’s when I started working in the studio for the first time, which was a game changer, opening up a new practice that was in conversation with the landscape work. I did a lot of these bananas long exposure pictures in the middle of New Haven with my view camera, that just felt like it was trying to… I was trying to un-know what I knew about making landscape pictures in a way. So that was the formative educational trajectory, but then once I got out of grad school, it took a long time to get those voices out of my head and figure out the work I really wanted to make, and sort of bring all these things together.

Building off that, can you talk a little bit about the choice for shooting with infrared and how you use that as a way to get more meaning out of the landscape?

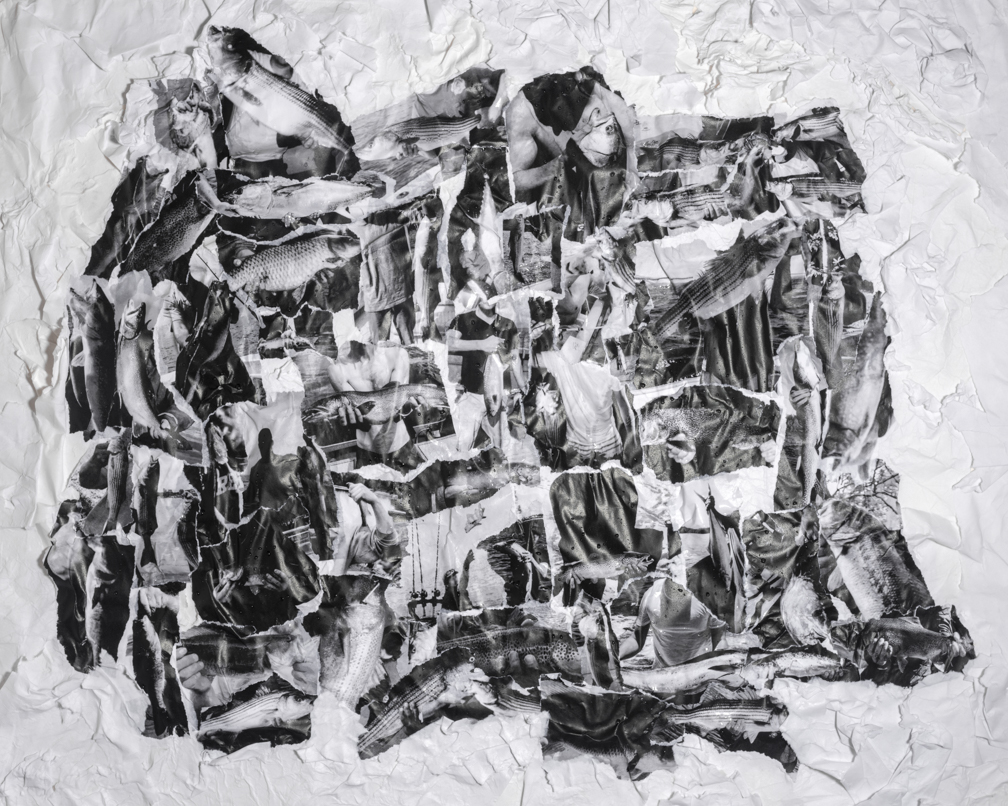

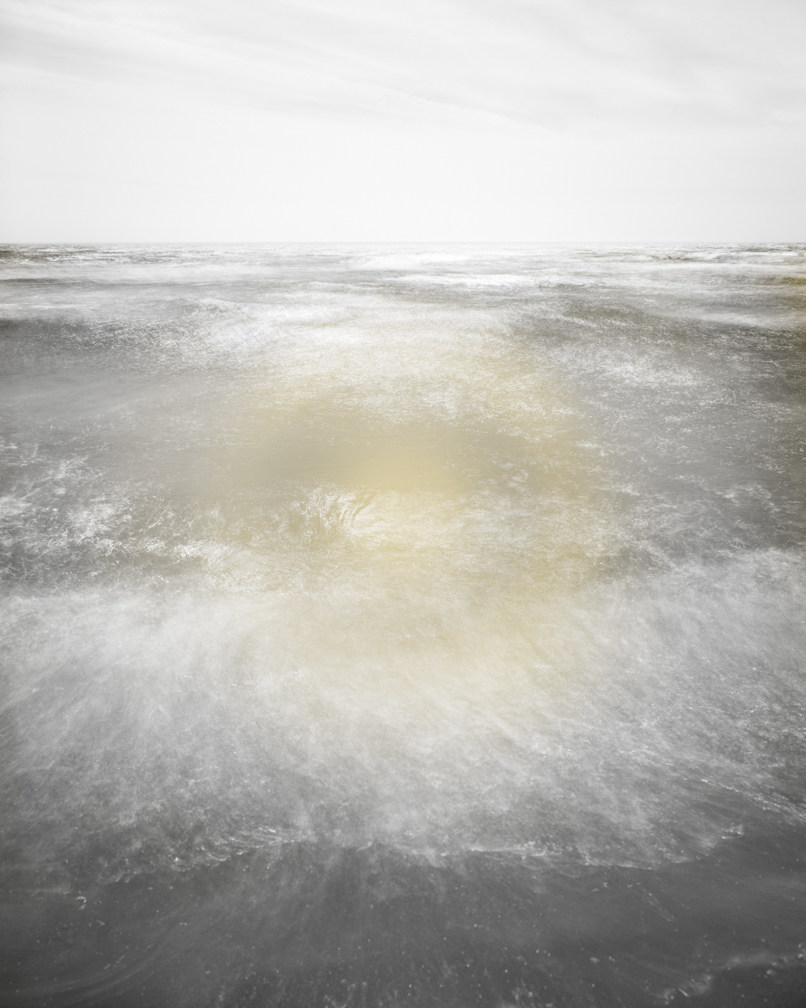

Yeah, I think I came to that when I was revisiting the Central Massachusetts pond landscape, and that was through the fishermen really. I had been working in the studio with that archive of the fishermen, and I just kept thinking about that pond, and that narrative there. And how fishermen were involved and… you know I wasn’t trying to connect those stories in any way but it was this sort of unresolved body of work that I thought I wanted to figure out in a new way. So I was there for months with just a camera and a flash trying to figure it out, and it occurred to me that what I really wanted to get at is what is unseen.

The idea of being able to filter out all the visible light through the infrared, and only reveal a spectrum that is not visible to the eye was a real turning point for me. It felt like a conceptual gesture that was sort of missing from the work.

Was there any media or some form of inspiration that led you to be so interested in the landscape, and its ability to hold onto or absorb history? Or what sprouted that interest and eventual investigation?

I think I’m interested in cultural mythology and the ways stories perpetuate through culture. And how, especially growing in New England, there are stories connected to so many specific spaces. When I was younger I was obsessed with all of those land art people, I was obsessed with Ana Mendieta and those kind of land artists who thought about the land in a really symbolic way. Robert Smithson would always talk about the substrata of disaster that landscape contains, and so I was really attracted to that work because of that.

I was never so interested in making stories through the camera, but I was interested in looking at places that contained stories. Which is harder since you can’t really let the viewer know what you’re looking at *laughs* but it’s what leads me to the place, and with the most recent landscape work… I was so fascinated by this sort of triangle in Massachusetts. It has all of these kinds of paranormal stories connected to them, and this one forest I ended up photographing over the course of several years, is known to be one of the most haunted forests in the world.

And you know, I have a lot of questions about that. It’s like stories that sit on top of one another, and that landscape in particular, it’s a story of settler colonialism. Which, in my opinion, is what’s really haunting us here, and so there’s so many things… I’m an overthinker in case you can’t tell… and photography really allows me to make sense of things in a way. Or at least it’s my way of making sense of the world… because you can’t make sense of it, but you can try to look at something closely over a stretched-out amount of time, and negotiate it in different ways, and try to get to a different understanding of it.

Kind of still in that same realm, how does ritual or the repetition of returning to a place play into your practice and how you explore a landscape?

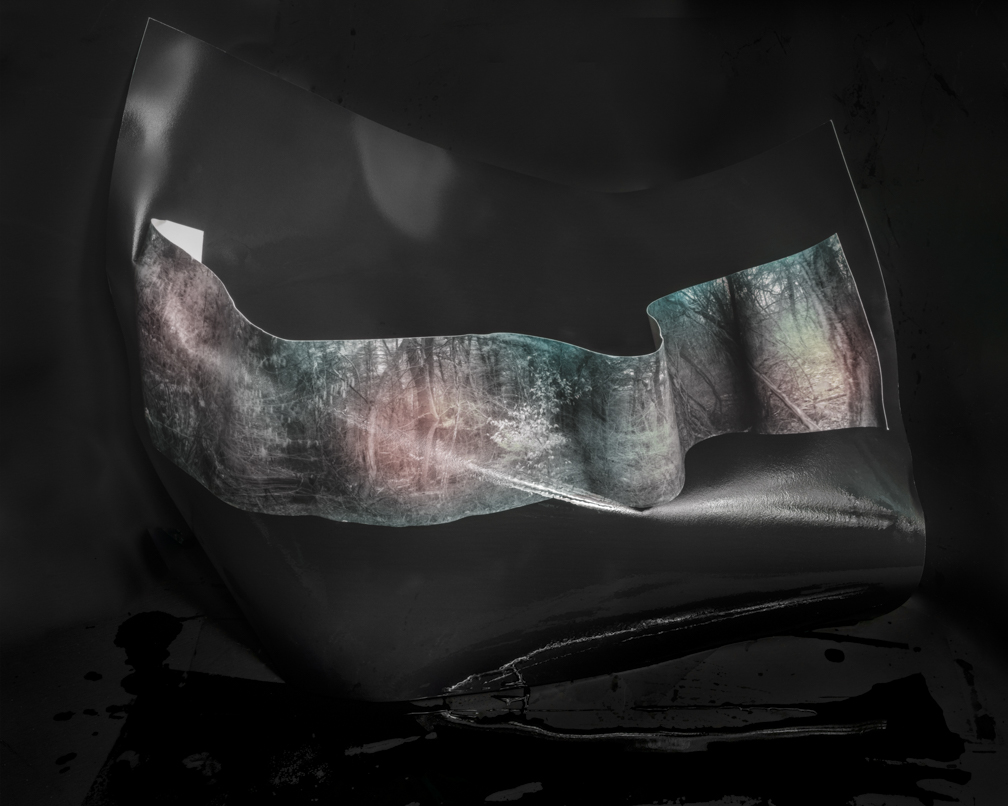

Once I’m interested in a space with a story I go back again and again and again and again over the course of several years. It takes me a long time to figure out how I want to eventually render or describe it. So, I’ll always be photographing, but with the forest, nothing clicked into place until I kind of translated it in the studio.

Speaking more about your earlier work, I feel like there was a theme of plant life and its intersection with the domestic. Can you talk about that interest, and if it was a motivator for making work?

That was definitely in my early work. Early on I was really interested in unsettling… there was this early series I made right after grad school when I was living in Northern California, where I was cataloging toxic house plants in this strange house I was living in. It looked like a set to me… and it kind of became paranormal in a way *laughs*

And I think that was probably the most personal work I ever made because my marriage was sort of unraveling, so it was kind of a reflection of my relationship to domesticity at the time.

I was like, “I’m going to look at these toxic house plants because I feel like one…” or like… there was a toxicity, and I felt the need to make the Vanitas or make a Dutch still life through the plant life.

So I think I moved away from that, domesticity isn’t something I really think about so much with my present work… but that definitely was a really personal body of work early on.

Is there any new work or interests that you want to talk about or share?

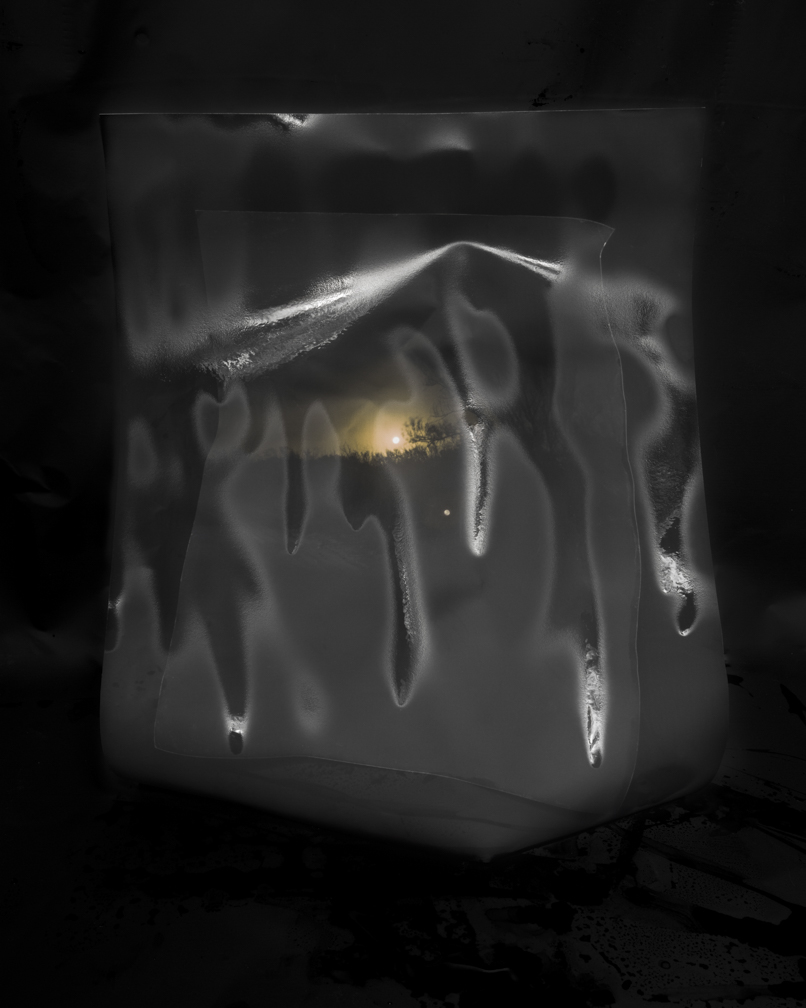

I don’t know how much I want to share right now, but right before I had to go back to Providence, I was spending a lot of time with this spiritualist church in Northport, ME. It’s a church of mediums, and I would go to services every weekend and it just felt so… I just became so interested in these women. Because you sit together and meditate, and then they give readings for everyone in the room of what spirits say, they can see things that I can’t.

And so I started this work in the studio that’s sort of “in-between things”. Meaning like it’s sculptural, it’s painterly, it’s a photograph, but it’s… kind of none of things too.

So I’m experimenting there with this idea of the in-between, and that’s sort of a new direction I’m heading in. It’s basically paper studies that are painted…

They’re kind of strange… they’re not a thing yet.

It sounds really interesting, I’ve heard a bit about the church in the past. So I’m really intrigued by it all!

It’s a little uncomfortable for me because it is really churchy in a lot of ways. Like I don’t feel totally comfortable singing from a handbook, but I’m so fascinated… I’m sooo fascinated!

Like there’s something palpably going on. I don’t think it’s fraudulent in any way, it feels very real while you’re there, these women are mediums. So just being in their presence feels really potent.

And this new life in the mid-coast… I feel like there’s something I’m really interested in swimming around in there.

Do you have a background interest in spiritualism and religion?

I think that I’m really really interested in what’s beyond the limits of the things we can know scientifically and structurally in the world… like “what is beyond that? How do we make sense of things that are beyond our understanding?”

And so I am definitely not a member of the spiritualist church… yet!

But I am interested in being around this matriarchal community that can see beyond what’s visible, like that’s my work in so many ways *laughs* so to be around people who embody that is really interesting to me.

So I am interested in… I don’t consider myself a spiritualist… but I am really interested in how photography has such a strange history that’s connected to spiritualism.

Kate Greene received an MFA from the Yale School of Art and a BFA from Massachusetts College of Art and Design. Her work has been featured in exhibitions at venues including: the deCordova Museum and Sculpture Park; the Institute of Contemporary Art, Maine; the Visual Arts Center at the University of Texas at Austin; the Rhode Island School of Design Museum of Art; the Guatephoto Festival, Guatemala City; Museum Dr888, Drachten, the Netherlands; Bodega Gallery, Philadelphia; Daniel Cooney Gallery, New York; and Eighth Veil, Los Angeles. Her work has been featured in publications such as the New York Times and has been favorably reviewed in the Boston Art Review and Art News. Greene has taught widely, most recently at Rhode Island School of Design, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, and the Hartford Art School Photography MFA Program. Greene currently lives between Providence, Rhode Island and Rockland, Maine.

She is represented by Grant Wahlquist Gallery.

Follow Kate:

Jake Benzinger (he/him) is a photographer and book artist based in Rockland, Maine; he received his BFA in photography from Lesley University, College of Art and Design in Cambridge, MA. His work explores the intersection of dreamscape and reality. Through the dislocation of space, he weaves together imagery to construct a world that exists in the liminal, investigating themes of duality, longing, identity, and the natural world.

His work was recently featured by Fraction Magazine, and has been exhibited both nationally and internationally. Jake’s body of work, Like Dust Settling in a Dim-Lit Room (Or Starless Forest), was recently self-published, shortlisted for the 2023 Lucie Photo Book Prize, and sold out of its first edition of hardcover books. A second edition was released in late 2023, coinciding with a solo show at the Griffin Museum of Photography.

Jake is currently a gallery assistant and workshop coordinator, a content editor for Lenscratch, and the founder/lead designer at wych elm press.

Follow Jake:

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Anne McDonald: Self-PortraitsFebruary 17th, 2026

-

Photography Educator: Erin Ryan StellingJanuary 9th, 2026

-

The Female Gaze: Alysia Macaulay – Forms Uniquely Her OwnDecember 17th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini G.E.LOctober 18th, 2025