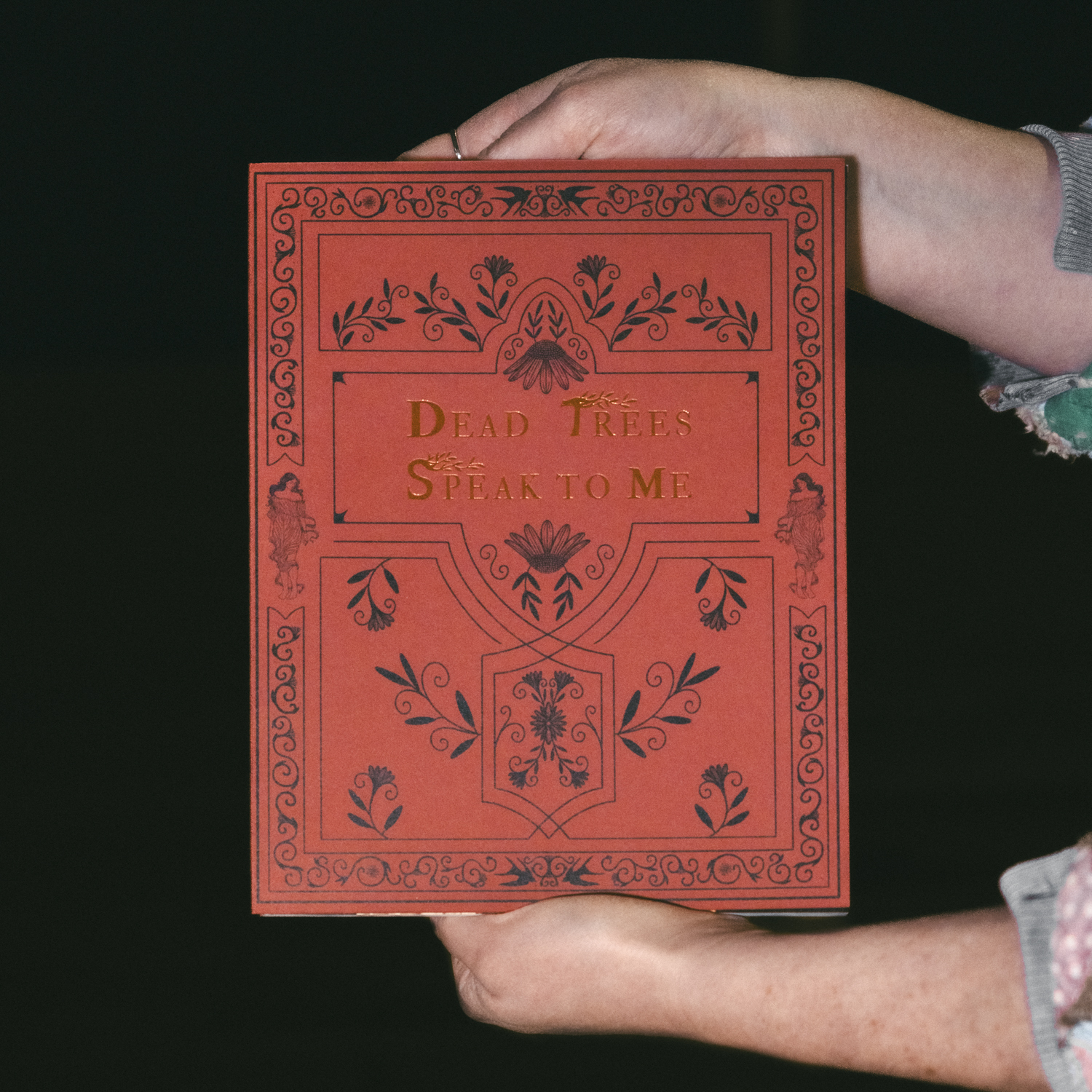

Interview with Tabitha Barnard and Jake Benzinger: “Dead Trees Speak to Me” and Independent Photo Book Publishing

“Dead Trees Speak to Me” is a culmination of photographs spanning ten years. Tabitha Barnard was raised oldest of four sisters in a close-knit Maine family. Through theatrical and fantastical image-making she explores the self-created mythos of her siblings, whose childhood was steeped in fairy and folk tales. Set against the backdrop of rural New England, their own rituals and legends took shape as children, exploring the woods behind their home and swimming in quarries. Fort Baldwin was transformed into Rapunzel’s tower; an abandoned fishing shack–a witch’s hut. As adults, they revisit these locations from childhood to experience the same magic. This collection of images weaves a narrative of sisterhood, isolation, blood, and desire.

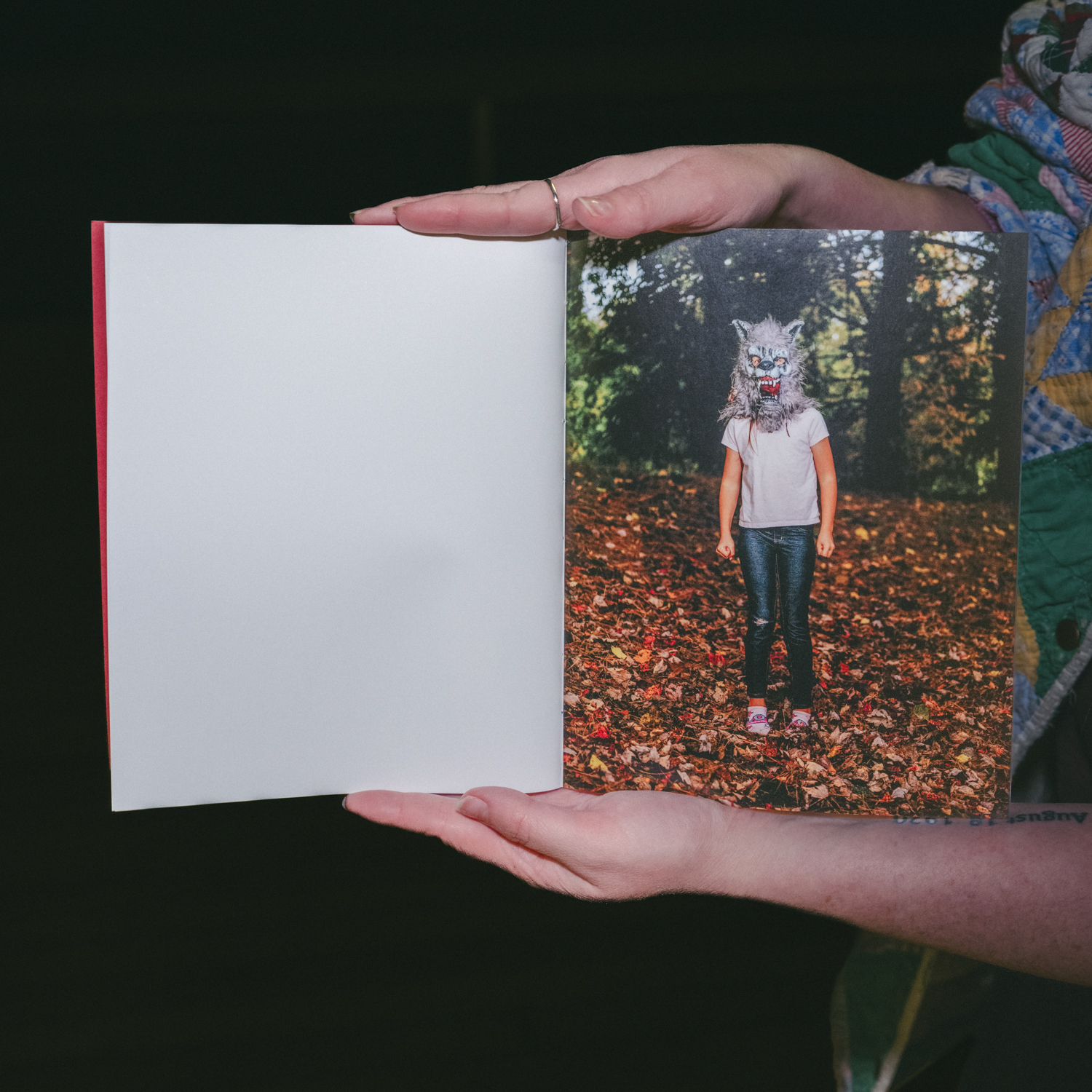

“In our childhood, my sisters and I loved folk and fairy tales. Our favorite ones were the ones that scared us. The ones that made the woods behind our home feel dangerous and exciting. Salem’s favorite was Baba Yaga—a witch whose house sat on chicken legs. Mine was Bluebeard, while Claudia and Grace preferred Heckety Peg.

In the forests of New England, we created our rituals, our mythos– ones completely insular to our quartet. Whether they were real or imagined didn’t matter. Folktales warned girls not to stray from the path, or obey their husbands. But in ours, we found freedom and power. My sisters became characters, never confined to just one role.”

I first learned about Tabitha’s work many years ago and have followed it from a distance. So what a wonderful surprise it was when I found out my friend Jake Benzinger was working with Tabitha on a book of her work! Sometimes these small world connections bring together the perfect people and ideas. I have seen the process of making this book, from the sheer beauty of the work itself to the painstaking effort of putting the pictures in the right order, to tell the story the way it ought to be told. Jake and Tabitha did this one right and the result is a debut book that is special in every way. When I flipped through my copy the first time I felt moved in a way a book has not moved me in quite some time. So of course I had to talk with Jake and Tabitha about the book: how it came about, where the inspirations came from, and the process of being a young artist and a young publisher nowadays. I hope you enjoy.

-Drew Leventhal

Drew Leventhal: Thank you both so much for being here. I’m really excited to have this conversation about publishing and about this new book you both put out together, Dead Trees Speak to Me. So Tabitha, I’m going to start with you. I actually found out about your work a long time ago. It might’ve been the Gomma Grant or right here on Lenscratch. But I remember seeing your work and thinking that it looked incredible and really very different from a lot of the other work that I had seen. Can you talk a little bit about how you developed your distinct aesthetic? Are you shooting film, digital? Can you talk about the colour choices that you’re making and how all of that came from your upbringing in photography?

Tabitha Barnard: I think it’s best to start chronologically. I found photography when I was in middle school and my dad got a DSLR for the first time. I have always been really obsessed with narrative storytelling and was not very good at drawing or writing. And so all of a sudden this kind of avenue of photography opened up where I could make my sisters kind of act out these stories for me and the camera. I started photographing them probably when they were in elementary school. Then as I got into high school, I was gifted my own digital camera for the first time. I was also really lucky to have a teacher that was a photo specific person. And so from all of that I got super super into photography specifically from a kind of narrative slash fashion perspective.

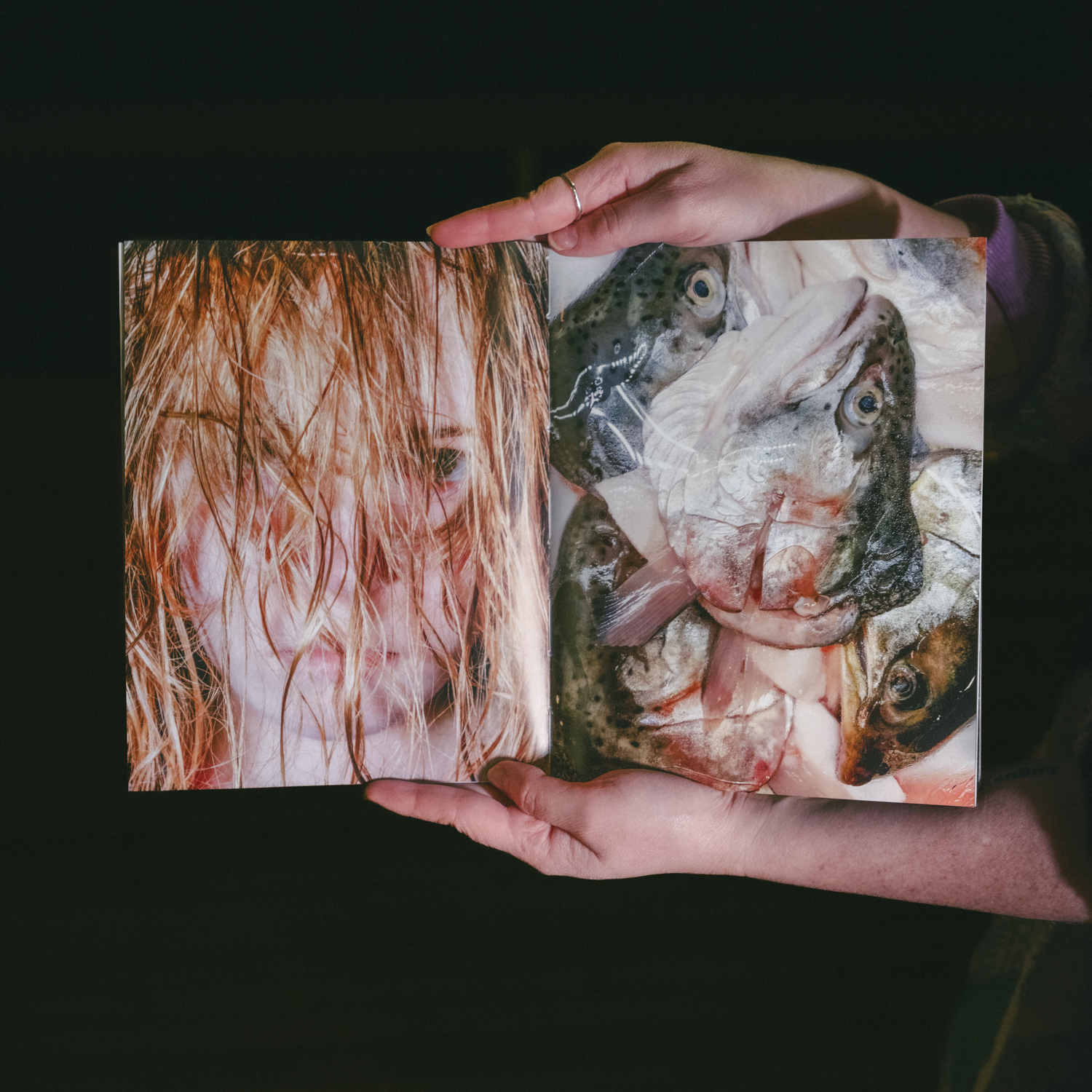

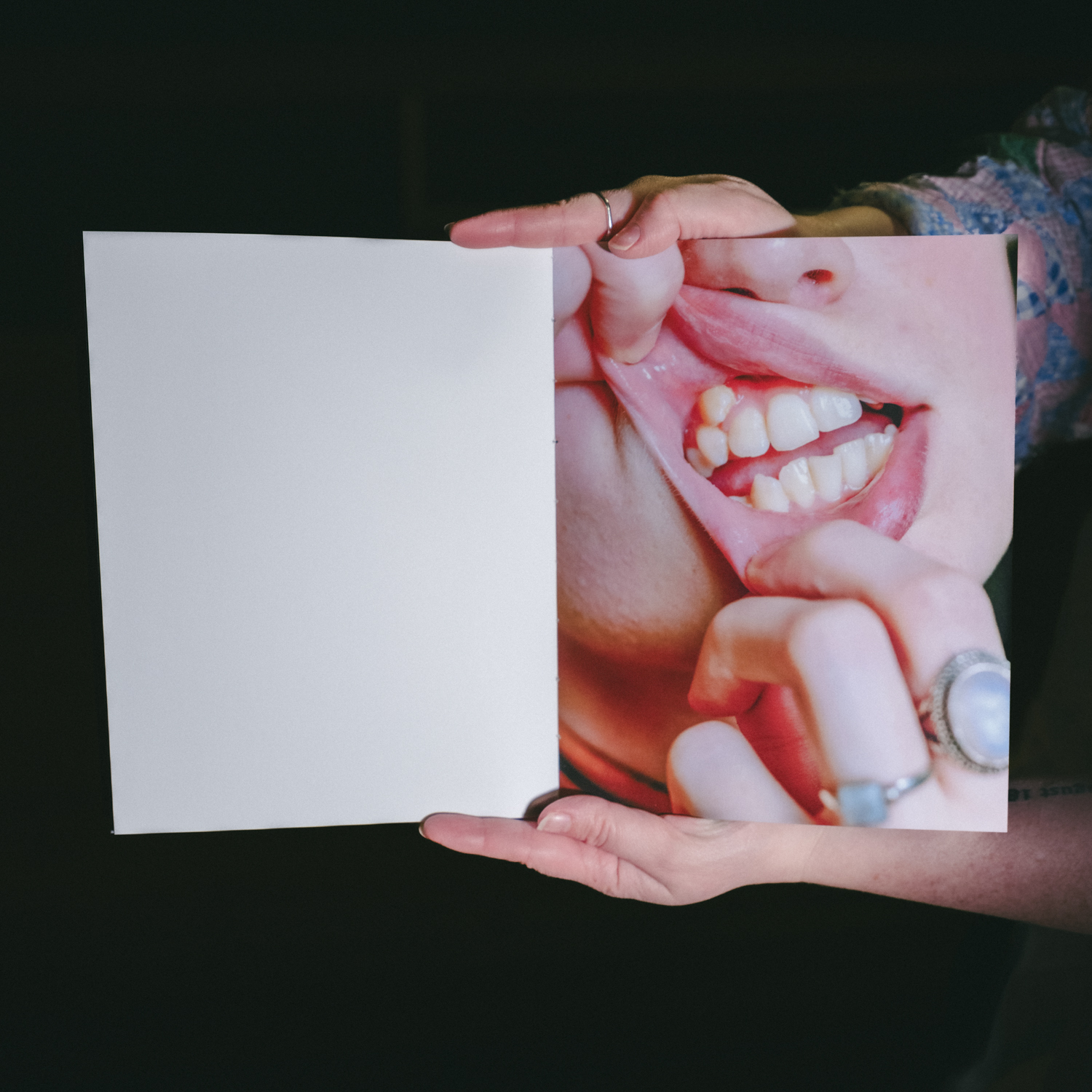

I think the visual language really developed from watching a lot of horror movies made in the 70s-90s. My sisters and I were super into them and even though my parents were pretty religious we were introduced to things like Interview with a Vampire (1994) and all of these crazy horror films that I never would ever think to have been interested in. And so this language of really bright flashes and a lot of red and this kind of almost melodramatic acting, it definitely stemmed from watching a lot of those types of films. Growing up, I was also obsessed with a lot of these really traditional witchy folk tales. Jake and I have talked about the story of Baba Yaga before, but I was also into this book that my mom read us. It’s called Heckedy Peg and it’s about a witch that turns kids into food and all the colours in that book are these bright reds and oranges So that definitely played a huge, huge part.

DL: Wow I didn’t know that you were influenced by horror films but now that you say it the references come to me very clearly. Are there specific horror movies that you were thinking about when you are shooting?

TB: Absolutely. The one that I always think about and reference all the time is Black Christmas (1974). It’s like a Christmas horror movie, which is kind of ridiculous, but it’s still super unsettling to this day. It’s set in a sorority house too, so it’s all women and it feels very 1970s, with all of that 35mm colour film saturation. Also the Village (2004) is great. That was one that I totally watched growing up. And anything like Fearless Vampire Killers (1967) my mom and I loved.

DL: That’s actually a great pivot to my next question, which is about this connection to femininity and religion in your house and how that has influenced your work. Can you talk about that and how that corresponds with horror? Those are the two things that I might not have put together originally. How did you forge a connection with your sisters through photography?

TB: Great questions. So I think in terms of religion and horror movies like I said, I was raised pretty religious. Both my parents, especially my dad, were really involved in our church, which was non-denominational Christian but definitely skewing towards more Baptist. I went to church camp as a kid and we had this old woman who would always teach the girls’ bible study and would just be doing the typical stuff, “You need to dress this way, you don’t want to be a temptation.” Our youth pastors were doing the same thing, creating huge pressure to settle down as proper women.

But the horror films became this huge fascination for me because most of them have this baked in Christianity component, and on top of that there’s the sort of final girl trope where the woman that survives is the woman that’s the most wholesome or good. I think that the subversion of that in a lot of horror is super interesting to me. I think horror is this really interesting space where women and oftentimes queer people can tell these allegories through the guise of this monster.

DL: It’s a reflection back on our own society, right?

TB: Absolutely. I read this book when I was in grad school too, where this woman is talking about girls often identifying with the monsters in films, not only because of the monstrous feminine and the body becoming this sort of space for horror in a Freudian way, but because they connect with the feeling of being rejected by society. And so I, the woman, sympathise with the monster who’s experiencing that rejection.

I’m lucky that all of my sisters (there are four of us total) are artists in some ways. My youngest sister illustrates and her twin writes and our middle sister Claudia is a huge ceramicist. And so they kind of got it right off the bat. But it definitely became a way for us to connect a little bit more, especially with my youngest sisters. When you have four people, not even just girls, you kind of split into teams pretty young. So when I started making photos of them, it kind of gave us this excuse to have to get along and bridge the gap a bit. It became almost a collaborative process where we’d throw out ideas for a photo. I’d be like, “Okay, we’re going to maybe try this.” And someone would respond, “That sounds like a Grace photo, that needs to be Grace in that picture, not Salem or Claudia.” So it has definitely brought us back to this space of being kids again, when we would have to play together because no one else is there.

DL: That’s awesome to hear. Jake, I’m going to pull you into this conversation. This is Wych Elm’s first big monograph. Can you talk about why Tabitha’s work felt like the right project to start with? Can you talk about the decision to do two books back to back with the same artist? You did the zine with Tabitha right before this new monograph. How did that model work and where the inspiration for that come from?

Jake Benzinger: So I had been thinking about launching a press for a few years now, and it was originally more of a self-publishing endeavor, but I wanted it to grow into something more. I released what was my undergrad thesis book and it picked up way more steam than I could have ever imagined. Within only 6 months, it got shortlisted for the Lucie Prize, sold out of its first edition, and got a solo show with Griffin Museum. It came at me all at once and straight out of school, it felt like an absolute whirlwind. Above all else though, it made me want to double down on starting the press and gave me confidence in what I was doing. Getting so much unexpected attention and praise felt so validating, especially amidst the transition from being a student to simply a practicing artist. I committed to launching the press late last December, after some conversations and encouragement from my friend Dylan Hausthor, and a really inspiring lecture and portfolio review with Dana Stirling and Yoav Friedlander from Float Magazine.

I formally announced the press by making a hand-bound zine with an artist I had become friends with, Sari Soininen. Alongside that project, drawing down the moon, I grandfathered in the remaining second edition copies of my thesis book, Like Dust Settling in a Dim-Lit Room (Or Starless Forest). The two of those projects were what I had at the beginning, and I got the branding done to officially launch Wych Elm in March of 2024. Ironically, the branding came out looking a lot like Tabitha’s work. We didn’t formally know each other at the time, but we had a lot of mutual overlaps and I think followed each other on Instagram. I was talking to one of our mutual friends and mentors, Kate Greene, and told her that I really wanted to work with Tabitha. She gave me a nudge, telling me that Tabitha would say yes, so I asked her, and now we’re here!

I’m really, really grateful to have gotten to work on this book and for it to be our first major release. Tabitha was the artist I wanted to work with the most, and I initially envisioned building up to it, so it’s a little surreal looking back on it now. I think it’s been seven months of work, we started in early March, right around the formal launch of Wych Elm. The zine, THE WOODS GLOW PAST MIDNIGHT, that you mentioned, came about rather suddenly over the Summer. I made it in one night because I’d just been spending so much time with Tabitha’s work and began seeing a lot of connections between our images. So, I put that zine together, it just sort of flew out of me. I texted her like, “Oops, I made a zine! Hope you like it!” There are a lot of pairings in it where my work feels like supporting images, and I think they uplift Tabitha’s really well. It came about only a few months into collaborating and was also at the point where we were discovering how in tune we are as artists. We share a very similar visual vocabulary and have a bunch of pretty uncanny parallels as people. It was a fun spur-of-the-moment way to generate some buzz, take a stab at pairing our work together, and also raise more money to fund the book.

DL: I’ll follow up because I wanted to ask about publishing and choosing artists. It’s one of the things that artists always ask me about as a publisher: How do you find or pick the artists that you want to work with? What are you looking for when you’re looking for artists to work with? Does Wych Elm have an overarching theme or aesthetic or is it one of those things where you know it when you see it?

JB: I think of the press similarly to a record label, it’s a collective of artists that mirrors my curatorial eye. Most importantly though, it’s a group of people that can become a community. From the moment I had opportunities coming my way, I felt strongly about sharing the momentum and any bit of platform I received, so Wych Elm is an extension of that. In terms of the selection of artists, my curatorial eye leans towards what I’m interested in and what is influencing my work. I’m very very fortunate to call most of my favorite artists friends, or to be half a person removed from most of them, like originally with Tabitha. To boil it down simply, the aesthetic is all things witchy, occultist, and inspired by mythos. Being immersed in the New England art community is almost a magnet for that sort of stuff, so it’s all come about pretty naturally.

DL: Let’s turn to the book now, I have my copy right here. Tabitha and then Jake, can you talk about the process of sequencing this book because it feels very smart and there’s a lot of visual motifs that I want to dive into. Correct me if I’m wrong, but all of the portraits are of your sisters?

TB: So we have worked on this sequence a lot together and it started when I sent over this huge chunk of work just all of the stuff and pieces that I’ve wanted to find a place for. I think that was a huge thing. I tried to think about the book as pieces that I really like but have never been able to show or feel like they are beside the point of a sequence that I was in. So this is a chance to get some of those little images their time to shine.

DL: Some pictures are really good for a book, but don’t do so well on the wall, and the same is true in reverse.

TB: Yes, exactly like that. Which is something we would always say in crits: that’s one for the book. It doesn’t belong on the wall. The other thing is that these pictures were made over a huge span of time, nearly 10 years. When I’m looking at such a wide breadth of time, what photos are going to still feel narrative and connected even with this huge gap. And it was really helpful having Jake and having someone else to look through this with me and see some of these connections that I had not seen.

We talked a lot about the sort of narrative that runs through it, making sure that it had that sort of semi melodrama without feeling like this is a bedtime story. And yeah, it’s all my sisters in the book. There’s a couple of instances where someone else appears, but I think the way that we’ve sequenced it and the pictures we’ve chosen, they’re kind of surrogates almost for the four of, or the three of them. The four of us.

JB: Yeah, the sequencing process was really, really, really fun. It’s my favorite part of being a photographer and bookmaker.

Initially, we were at a crossroads, we were like, is this going to focus on psychological tension or more on “girl summer”? We chose psychological tension. What eventually became the interlude to the book, the first eight spreads before it’s broken up by the publisher name, is the project’s heart. This short sequence is pretty close to what I originally presented to Tabitha as a potential direction for the book. We started by constructing these runs of photos that set the mood, atmosphere, and what we wanted the narrative to be, and then we built out from there. That’s typically how I approach creating a book, giving it a heart, and then building around that core. We had a bunch of Zoom calls, in-person meetups, and have had an ongoing text conversation throughout the whole process, usually going back and forth a little bit every day or two.

That beginning run has stuck through since the very start and sets the stage for the book. Thinking of sisterhood as a coven is what made it fully come together though. Sisterhood is so core to Tabitha’s work, and it was a little absent at first. Finding a way to incorporate it into the narrative structure and atmosphere set in the opening was the aha moment. Also, there’s almost this passing of the torch where Claudia (one of Tabitha’s sisters) is the witch or Midsommar-esque May Queen at the beginning. Then, throughout the sequence, it’s almost as if it gets passed on to Grace (one of Tabitha’s other sisters) by the end, there’s even a full circle moment where the initial image after the interlude is of Claudia, with a crown, and the final image is of Grace with one.

DL: Tabitha, you mentioned that this is a long period of time of work. This is like 10 years of work, right?

TB: Just under 10 years yes.

DL: What I wanted to ask about is how you have changed as a person and as an artist over this time. Personally, I take different pictures now than I did 7, 10 years ago. How did you see those pictures changing and how did you all think about incorporating older pictures into the newer ideas that you’re thinking about post grad school? How is that meshing process?

TB: My practice started around the documentary tradition where I was really just interested in my own family dynamic and my sisters specifically. Since then it’s evolved a bit to become more theatrical. It’s a lot more tableau specific. It’s not so much in the book, but I think things have shifted a lot now that I have my sister-in-law, my brother-in-law, and my husband in the pictures. They have started to play different characters in our family.

DL: There’s a couple motifs that I wanted to jump into. Ritual is obviously a huge one. Jake. I’m going to go back to this initial sequence that you were just talking about. These first eight pictures here. I really do think it’s a brilliant little bit of sequencing here. Can you talk about what visual motifs you were trying to establish with this opening sequence? It builds the foundation for the rest of the project. You have to establish your themes early so that later on when you bring them up and reference them, people are not shocked.

JB: Early on Tabitha and I pretty quickly realized that we have a lot of similar niche interests in media. Suspiria (1977) was a really big one and super important to a lot of what we’ve been talking about thematically. The movie follows a cult of witches being unraveled and discovered in an all-girls school. I think that ominous underbelly of something being off, yet slowly revealed and not explicitly shown for the longest time, is what we keened in on. In the book’s opening sequence, there are a lot of biblical references as well. That was the question for us, how do we access those feelings and imagery quickly in the book? Everything else afterward is characterized and informed by what came before, which can be quite transformative in some cases. In the interview I did with you and Owen, we talked about how we all react going through a sequence. I have a very physical reaction as I’m going through a book. I bob my head forward with each page turn, almost rhythmically, and if it doesn’t feel right and match my physical cadence, it’s off. Sequencing to match the narrative flow of a song or an album is really important to me.

DL: One of the things that I noticed in the opening section is that there’s no pictures that hit you right in the face, direct eye contact with the camera. It actually feels like you’re kind tiptoeing a little bit around what’s happening. And then you get to the proper “start” and the first picture is bam, right in your face. I actually really like this slow, gradual, almost ominous, buildup. And then you hit get the flash to start off the story proper.

JB: I think what you just described is more in line with my way of image-making. I almost always conceal faces and keep things at a distance. There’s this thread of tiptoeing around and navigating the tension of confronting something. I love that ebb and flow of tension, getting really close to snapping, but then reserving, maintaining the build-up, and continuing that rise and fall. I’ve even photographed Tabitha and she has her hair flipped over her face. I typically conceal identities and faces, so I think what you described just comes from my approach to her work as an editor. It’s a bit of my narrative spin on Tabitha’s incredible images.

DL: That just shows the relationship that the artist and the publisher have to have together. It has to be a combination of two sets of eyes and languages.

TB: We didn’t have a single disagreement and were totally aligned making the book from start to finish. I couldn’t be happier to have an experience like this for the first book.

DL: I just have one question for both of you. What’s next? What’s coming after this?

TB: That’s a great question. I personally have no idea right now, but I think that’s kind of nice to just sort of be letting it happen a little bit. I think this book was a really amazing project to work on and it’s definitely gotten me excited to go out and make new photographs. But I think I also need to sit for a second and absorb.

JB: I’m really antsy to get back into making work. Tabitha and I have a two-person show next May, so I’m excited to dive into that. I haven’t had time to think about my own practice lately, so regardless of working together or alone, I want to make more images. Wych Elm also has some more books in the pipeline, nothing I’m ready to share yet, but definitely some cool releases set for next year.

DL: That’s awesome. Thank you both for doing this. I really appreciate it.

Click here to purchase “Dead Trees Speak to Me”

Tabitha Barnard (she/her) is a photographer who grew up as the oldest of four sisters in rural Maine. She works primarily in analog color photography, exploring themes of femininity, religion, and ritual. She received her Bachelor of Fine Art from the Maine College of Art in the Spring of 2016 and her Master’s degree in Fine Art Photography from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in the Spring of 2021.

Tabitha currently lives and works in Portland, Maine, teaching at the Maine College of Art and the University of Southern Maine.

Follow Tabitha Barnard:

Jake Benzinger (he/him) is a photographer, book artist, and writer based in Rockland, Maine; he received his BFA in photography from Lesley University, College of Art and Design in Cambridge, MA. His work explores self-created mythos, and through the dislocation of space, he weaves together imagery to construct a world that exists in the liminal—navigating the space between fiction and reality and investigating themes of identity, mysticism, animism, and death.

His work has recently been featured by Float Magazine, Transference Magazine, and Fraction Magazine, and has been exhibited both nationally and internationally. Jake’s body of work, Like Dust Settling in a Dim-Lit Room (Or Starless Forest), was self-published, shortlisted for the 2023 Lucie Photo Book Prize, and sold out of its first edition of hardcover books. A second edition was released in late 2023, coinciding with a solo show at the Griffin Museum of Photography.

Jake is currently the assistant gallery manager, associate curator of photography, and curator of books at Blue Raven Gallery, a content editor for Lenscratch, and the founder/director of wych elm press.

Follow Jake Benzinger/wych elm:

Drew Leventhal (he/him) is a photographer working with themes of colonial history, family, and the way memory shapes identity. He attended the International Center of Photography and completed his MFA in photography at the Rhode Island School of Design.

Valley Books is an independent publisher of photography books. We focus on small run, handcrafted books that elevate the images they contain. By blending the photographic monograph with the traditional artist’s book, we want to create unique objects that will stand the test of time.

Valley Books was founded in 2023 by Drew. It began as a way to combine his passion for bookbinding with a desire to publish the books he wished existed.

Follow Drew Leventhal/Valley Books:

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Michael O. Snyder: Alleghania, A Central Appalachian Folklore AnthologyJanuary 18th, 2026

-

David Katzenstein: BrownieJanuary 11th, 2026

-

Amani Willet: Invisible SunJanuary 10th, 2026

-

THE 2025 LENSCRATCH STAFF FAVORITE THINGSDecember 30th, 2025

-

Kevin Klipfel: Sha La La ManDecember 29th, 2025