Photographers on Photographers: Claudia Ruiz Gustafson in Conversation with Ana De Orbegoso

©Ana De Orbegoso, Saint Rosa of Lima, 2007

When Lenscratch contacted me to do an interview, I immediately thought of Ana De Orbegoso. Ana is also a Peruvian artist living in the USA. I have actually never met Ana in person. A few years ago when I was in Lima visiting my family and doing my usual gallery and museum tour, I stumbled upon an exhibition that took my breath away: “Virgenes Urbanas (Urban Virgins)”. It was in a gorgeous gallery in the heart of downtown Lima. The gallery felt like a magnificent temple with walls covered by large paintings by the Escuela Cusqueña (Cusco School is a Roman Catholic artistic tradition based in Cusco, Perú during the Colonial period, from the 16th to 18th centuries). But when I looked closer, I realized that they were photo composites that Ana created by placing indigenous women and children’s faces and hands on the paintings. That immediately became a powerful political statement for me. This reminded me of my first trip to Cusco where I learned that the Quechua people painted the Catholic Virgins with huge puffy dresses shaped like mountains, because contrary to Catholic [teachings] they surreptitiously adored the mountains. I admire when artists are able to blend art and activism, after that experience, I have been following Ana’s work from afar. Her latest work is a video titled “La Última Princesa Inca (The Last Inca Princess)”. This piece is now touring important archeological sites in Perú. But let’s start the conversation now.

Ana De Orbegoso is a New York based Peruvian/American interdisciplinary visual artist. She explores the politics of gender, race, identity and historical memory in videos, photography, and multimedia productions that incorporate performance, projections, and audience interaction. Through the use of popular iconography, her aim is to confront the viewer with a mirror, so as to spark thought and memory.

Ana De Orbegoso is a New York based Peruvian/American interdisciplinary visual artist. She explores the politics of gender, race, identity and historical memory in videos, photography, and multimedia productions that incorporate performance, projections, and audience interaction. Through the use of popular iconography, her aim is to confront the viewer with a mirror, so as to spark thought and memory.

De Orbegoso is a 2008 fellow in Photography from the New York Foundation for the Arts. She received grants from NALAC – National Association of Latino Arts & Culture; En Foco New Works Awards and Julia Margaret Cameron Award among others. Her video art “The Last Inca Princess” was awarded Best Experimental Short at the 2015 Big Apple Film Festival and the 2016 California Women’s Film Festival, with a Special Juror’s mention at the 2015 World Festival Cine Extremo de Veracruz, Mexico.

Her work is in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago; the National Museum of the Women in Washington D.C.; the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Perú; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Lehigh University Art Galleries, Penn.; MALI Museum of Art Lima; Museo de Arte U. San Marcos, Lima; ICPNA Peruvian North American Cultural Institute, Lima and the Joaquim Paiva Collection at the Modern Art Museum of Rio, among others.

Her project “Urban Virgins”, a decolonization project, is being continuously exhibited since 2006 around Perú’s different regions, along with a performance with local artists’ participation. To this day it is the most locally exhibited art project in Perú. Instagram: @anadeorbegoso

Claudia Ruiz Gustafson is a Peruvian-born, Massachusetts-based visual artist, educator and curator. Her work is mainly autobiographical and self-reflective, often portraying themes of femininity, memory, dreams and personal mythology. She regards image making as a powerful medium for exploring her inner world.

Claudia has exhibited in museums and galleries across the US and abroad at venues including the Danforth Art Museum, Agora Gallery, Millepiani Gallery, Galleria Valid Foto, Fountain Street Gallery, Griffin Museum of Photography, Cambridge Art Association, Concord Center for the Arts and the RI Center for Photographic Arts. She had her first solo show in 2020 at the Multicultural Arts Center in Cambridge, MA, titled “Historias de Tierra y Mar (Stories of Land and Sea)”.

She has received grants and awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Cambridge Art Association, L.A. Photo Curator: Global Photography Awards, PX3 de la Photographie Paris, and The Gala Awards, among others.

Claudia has self published several books that incorporate her photography and poetry. She is the owner of a portrait photography business and also teaches creative photo workshops in the Boston area. Currently she is curator and participating artist of the traveling exhibition “Crossing Cultures: Family, Memory and Displacement”, a multi-media project made up of artwork created by multi-cultural artists reflecting on identity and diaspora. Instagram: @claudiaruizgustafson

©Ana De Orbegoso, Video Still “The Last Inca Princess”, 2015

Claudia Ruiz Gustafson: Tell us about your growing up in Perú and what led you to becoming an artist.

Ana De Orbegoso: I come from a family that has been very present in Peruvian history. From my father’s side, my great-great grandfather fought in the Peruvian independence war against the Spaniards. My grandmother was very creative and she motivated me to do art through arts and craft kits, which I loved. My mother, a composer, was passionate about Perú, and I learned to love it as a child through her music. All this gave me a strong awareness of both the beauty and the problems of my country and caused me to question what I saw — to be more reflective about it. One day I left Perú, leaving everything behind with the determination to find the way to become an artist. I loved Perú, but the world was bigger. Through art I wanted to find the meaning.

©Claudia Ruiz Gustafson Tus calles mientras dormías, 2020

AO: Claudia, you are also Peruvian yourself, how did you grow up?

CG: My parents were very young and very poor when I was born; my father’s first job was a door-to-door encyclopedia seller. We didn’t even have a proper home, but a temporary drafty construction on the roof of my grandmother’s town house. You are lucky your mom was an artist; my family never encouraged me or my brother to be interested in art. I don’t ever remember going to a gallery or museum until I was in college, where I became a socialist, a nationalist, a feminist and discovered photography. I am grateful for my college education.

My family, despite their humble origins, were very racist. I remember when I was a child they used to tell me who to play with and not to play with. Racism is very systemic in Perú, very open and very damaging. Even though my parents struggled earlier on, my father went to become a manager in one of the most important pharmaceutical companies in the country. He is very intelligent but he also benefited from his lighter skin, had he been darker, the story would be very different. Every time I visit Perú, I see progress but it is way too slow.

©Ana De Orbegoso, Neo-Huaco 3, 2016

CG: As I mentioned in the introduction, I admire you because your art is also a form of activism. Even though you are based in New York, your art is very much rooted in our country. Do you consider yourself an activist?

AO: It was really very exciting to receive your invitation. Thank you Claudia, and I deeply appreciate that it has opened my horizons and let me get to know about your powerful and interesting work.

Do I consider myself an activist? I believe life has made me develop the protester in me. Since I was young in my country I questioned why there was numbness, a kind of lethargy in everybody’s attitude towards national issues. Racism, discrimination and abuse were natural. As an adolescent I went to marches. At the same time I discovered what an incredible tool photography was to express my opinions. Later I understood also, that as a woman in our society, I was going to spend the rest of my life protesting. It may sound ironic that living here I wanted to do works based on Peruvian history. But Perú is where my heart is, and I wasn’t going to change my trajectory just because I wasn’t there physically all the time.

©Claudia Ruiz Gustafson, Los que se fueron, 2017

AO: Your work is self-reflective and deeply immersed in personal memory. Memory connects me to loss and longing. Do you feel your work serves you as a connection in order to close the circle of your memories, to convey a sense of loss? Is this what connected you to do art?

CG: Yes, my work always has an autobiographical element. I also feel that the themes are recurring. I feel I am always going through the hero’s journey over and over again. Memory plays an important part in my family trilogy series. It all started with the death of my last grandparent. I received a phone call that rushed me to the airport, but I arrived too late and couldn’t say goodbye to my grandmother. She was the family storyteller, the storykeeper. When I returned from that trip I brought with me a suitcase full of photographs and memorabilia that she wanted me to keep. She was passing me the storytelling baton. Along those photographs were letters and other documents in which I learnt many secrets she took with her. That embarked me on exploring and piecing together the story of my family from both sides and starting “Historias Fragmentadas (Fragmented Stories)”. To go back to your question, yes, this project is important to me, connects me deeply to my culture, to the ones who are not longer here and makes me understand myself better.

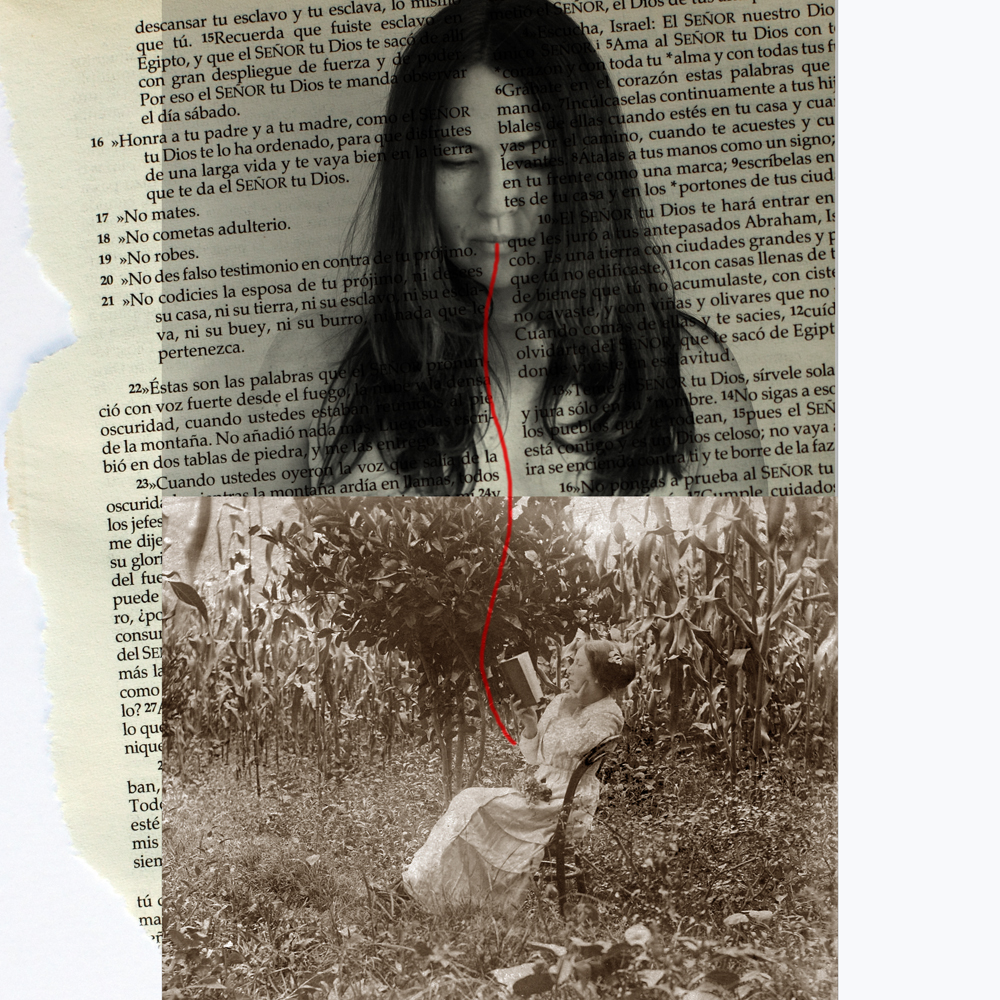

©Claudia Ruiz Gustafson, Lazos de sangre, 2017

AO: I have a fascination with collages. Your works have a narrative, they tell stories. In your series “Fragmented Stories”, the compositions have layers. You construct your ideas with objects, people and texts placing them in situations that invite the viewer to dig deeper. In fact, it is a thread in most of your work. Do you write scripts for your pieces?

CG: Most of my work is conceptual; I normally do some writing and draw sketches before I start shooting. In the case of “Fragmented Stories” that didn’t happen because I was working with an array of objects so my practice was different. Every morning I would arrange and rearrange objects from that suitcase I brought from Perú. At the beginning of my practice those compositions were mainly digital but later on, they were physically arranged on a white cardboard and photographed. For that project, I also used staged imagery, mostly self-portraits, to transport my physical presence into the spiritual past as seen in the compositions. That project took five years in the making. The story of my family is a piece of the Latin American experience, a story that is not told enough here in the US. The thread is perhaps my own story and the story of the people who came before me.

©Ana De Orbegoso, The Virgin of the Musket, 2007

CG: Ana, you also work with collage in your “Urban Virgins”, tell me more about this project.

AO: Baroque colonial paintings and relics of our past cultures are part of the iconography that surrounds us as children growing up in Perú. It came naturally to me to use these symbols in my work as they were a common language. Besides being religious symbols, these paintings are our historical objects. But what struck me about them is that they don’t talk about my culture but of another culture, that of the conquistadors. I decided that it was time to reclaim these images and to decolonize our history. Using paintings from the School of Cusco, I created digital collages, substituting Spanish characters, backgrounds and symbols with images that reflect the cultural, spiritual and physical diversity of present-day Perú. I traveled around the country to immerse in history and take photos of people, ancient objects and archeological sites.

And then I created “Urban Virgins”, new non-religious and non-colonial icons to represent Perú. As these were mostly Andean figures, I wanted to honor their culture by including messages in Quechua so I invited Odi Gonzales, a Cusco poet, to collaborate in this project by giving voice and daily life to the characters of the works. I opened this project in Cusco. The life-size canvas photos were installed at the entrance patio of the Inka Museum, a patio also used by native artisan weavers hand- working alpaca wool. The day of the inauguration I realized that this exhibit had to travel around Perú, visiting its own country. What comes from the land goes back to the land.

©Claudia Ruiz Gustafson, Qué solo me he quedado en esta sombra tan sóla, 2018

AO: Can you talk about the other two chapters of your family trilogy “Poet of the Lake” and “María”? Have you thought of doing more projects in our country?

CG: “Poet of the Lake” is a project I created in memory of a family member I never knew personally but whom I identified with the most myself. He was first generation Peruvian Italian, lived in Puno, Perú and dedicated his life to writing poetry about the beauty of the Aymara culture. He was a social justice advocate and a critic of the system that exploited the indigenous people. He struggled with alcoholism and died in 1958, his last poem was about the impossible love between him and an Aymara woman.

In 2018 I traveled to Puno and found out he has an entire plaza and a monument named after him in his honor. His poems had been adopted by local indigenous organizations who are reclaiming their heritage and when I asked kids in the streets if they knew who Dante Nava was. “Yes,” they replied, “he is the Poet of the Lake.”

©Claudia Ruiz Gustafson, La estampita de María, 2020

“María” was entirely shot in my family home in Perú, this past January, right before the pandemic. That house is very special to me and holds a lot of ancestral energy. There was a lot of synchronicity while working on this project, including the way I found my model to represent María, a maid who lived with us for many years and who influenced me deeply. This was a project to honor her, an important woman in my life. “María” is connecting and resonating with so many people and taking a life of its own. That and this interview, your work Ana, I think that’s a sort of message for me. I feel now I want to go back to where everything started, I need to go back to my roots, my culture and draw from there.

©Ana De Orbegoso, Video Still “The Last Inca Princess”, 2015

CG: Tell us about your video “The Last Inca Princess”. How has been the receptivity in Perú? Do you have plans to bring it to the international market? I love its message of resistance!

AO: “The Last Inca Princess” was the most ambitious project I had envisioned. As a photographer, I had worked alone or with small crews. This time I had to look for collaborators, a producer, an assistant director, actors, fashion designers, composer, choreographer, technicians, locations (a theatre, an archeological site and a guinea pig farm among others) and a whole set of technical equipment. Not too many art videos have been done in Perú on history. It was an intricate project to elaborate, and promised myself to enjoy the process, and I managed!

The piece brought to life a colonial painting from the School of Cusco documenting the marriage of the last Inca Princess to a Spanish captain. The 15 minute film is a reinterpretation of the historical events behind the painting that give crucial answers to Peruvian history. Its narrative axes are the experiences and memories of the princess. She represents the passing of the transcendence from her mother to her, and from her to her mestiza daughter. The video documents the story of this character and her daughter, communicating a message of feminine resilience and the struggle to maintain an ancestral identity.

This project includes not only the film but a multidisciplinary installation, including animation and virtual games, which was first presented at Lima’s Museo Pedro de Osma. Since then we have created a multi-media show around the film. We travel around the country, projecting the video on the structures of millenary pyramids and presenting a live song and dance performance, with the participation of the singer Sylvia Falcón and Miriam Sernaqué, the actress/dancer of the video.

©Claudia Ruiz Gustafson, María, 2020

AO: How do you navigate in the artistic world? How do you get into exhibits? How do you find exposure for your work?

CG: This is where I struggle because I don’t have much time or money to promote my work. Besides my fine art practice I run a portrait and event photography business and I have a child with special needs. I have never been to a national portfolio review, except for the ones that are offered in my own state. It’s my hope that now with the new online platforms like Zoom these events can now be offered online so more artists can benefit. I also find that a great way to democratize the arts is to apply directly to curatorial proposals, and those have been amongst the most rewarding experiences of my career so far. Let’s think of projects that include collaborations, diversity in ideas that are able to move us, question us, inspire us to action and help us become better humans. That should be the purpose of contemporary art, I think.

©Ana De Orbegoso, The Virgin of Mercy, 2007

CG: What about you Ana? You have an impressive resume!

AO: Thanks Claudia. I believe that time makes a resume, but I do understand your point. Navigating the artistic world was quite a challenge for me too. I didn’t have the money to study for an artistic degree, so I took non-matriculated classes at the ICP, SVA and NYU. Getting into the art world in New York hasn’t been easy as I didn’t belong to a local group and didn’t have a mentor here.

On the other hand, the fact that I was not living in Lima made it also difficult to maintain my presence there, but being that it is my hometown I managed well. My art practice has been crucial in my life. It held me together through vulnerable times from the feeling of displacement that comes with living between two cities. Being far from Perú allowed me to reflect with more objectivity about it, opening a space of questions and answers that resulted in the work I originated. Opportunities arose by presenting myself in person, by applying to grants and contests, also exhibit invitations came as my work started to be more known. I do agree with you about the democratization of art — it should be experiential within a community towards the quest of becoming better humans.

CG: What would you like your art to accomplish?

AO: I consider “Urban Virgins” the most complete work I have done, it closes a circle. Not only did it let me give back to the land, but it gave me life. As artists, we create, then we exhibit, and then we put that show on hold because we have another one on the way. So the creations “die” and sometimes a long time passes until they come back to “life”. The virgins will never die, they are alive and will keep that way because they don’t have a restriction, they are on the road honoring community after community every time, and by that, they will keep on bringing me life. This, I feel, I could only accomplish because the subject matter doesn’t belong to me anymore, it belongs to an immense community, so I cannot take it lightly. It is their story, it deserves much respect. This is what I would like to continue to accomplish with my works, that they will take on a life of their own.

©Claudia Ruiz Gustafson Yaw Yaw Puka Polleracha, 2020

AO: I love to be surrounded by art, going to exhibits exhilarates my life and I love to see the work of other artists. It inspires me. Are there many artists who have influenced your work?

CG: I love your process. I also love going to exhibits, galleries, museums, art films, and live theater. I devour the books by Isabel Allende and Carlos Ruiz Zafón, who died recently. I would never survive in the wilderness or the countryside for too long. I love art, I love culture and even though I am an introverted, I love people and their stories, so the pandemic has really affected me. I am now spending too much time in front of my computer. Artists who have influenced my work? I feel in my early work I was strongly influenced by the mystery of Francesca Woodman and the lyricism of Julia Margaret Cameron’s images. Recently, I have discovered the films of Andrei Tarkovsky who has become my favorite filmmaker. I already see myself going in that direction, creating bodies of work that tell the story of a unique human being including his/her inner life, his/her dreams, fears, and nightmares.

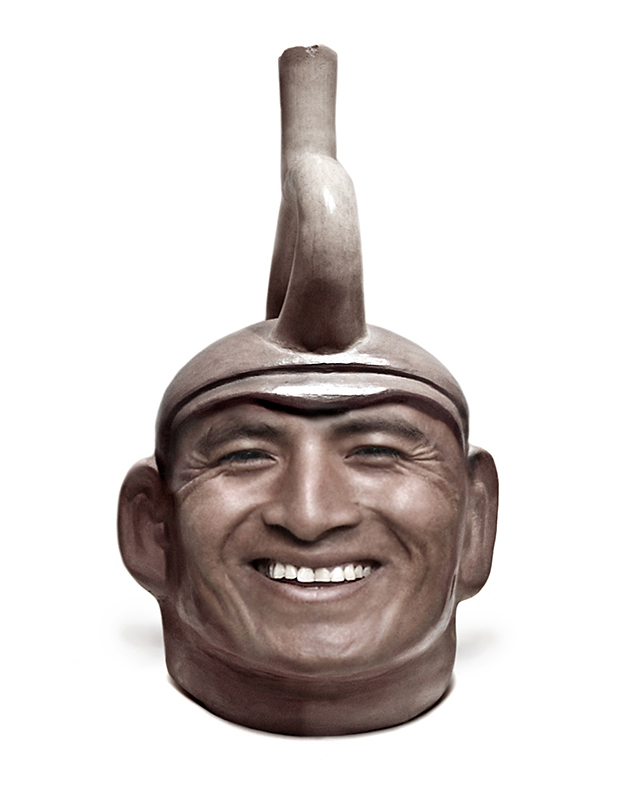

©Ana De Orbegoso, Neo-Huaco 1, 2016

CG: What’s next for you, Ana?

AO: With “Urban Virgins” I had nailed an important subject I wanted to bring attention to — racism, discrimination and gender equality. “The Last Inca Princess” continued this line. Closing the trilogy was “So what do we do with our history?” in which I reinterpreted ancient Mochica portrait ceramics. All of these were inspired in ancient iconography to reflect on the present. I have now turned my attention to reclaiming a different history and memory.

My recent work “Feminist Projections” is geared to supporting the women’s movement for equal rights. In order to keep the conversation present, I walk around the city wearing a Power Vest I created, projecting images of women empowerment in all kinds of places, buildings, objects and on people. I showed the first iteration of this project in February in Zona Maco in Mexico. But there is more to come. It is still in development. What’s next? Keep going. Never stop.

©Claudia Ruz Gustafson, Como un cielo Puneño en el crepúsculo, 2018

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Ben Alper: Rome: an accumulation of layers and juxtapositionsJanuary 23rd, 2026

-

Suzanne Theodora White in Conversation with Frazier KingSeptember 10th, 2025

-

Maarten Schilt, co-founder of Schilt Publishing & Gallery (Amsterdam) in conversation with visual artist DM WitmanSeptember 2nd, 2025

-

BEYOND THE PHOTOGRAPH: Q&A WITH PHOTO EDITOR JESSIE WENDER, THE NEW YORK TIMESAugust 22nd, 2025