Dillon Bryant: From There to Here and Never Back Again

This week, we will be exploring projects that use the found photograph. Today, we’ll be looking at Dillon Bryant’s series From There to Here and Never Back Again.

I first became friends with Dillon Bryant when we were both in our undergraduate education at the University of South Dakota. I remember him constantly being found in the Photography Studio, whether he was working in the darkroom, scanning prints, or cutting out images for collages. Dillon is one of the most approachable and kind people I’ve ever met. He’s so excited about whatever you’re doing in the arts and to share his ideas.

Dillon is able to capture the feeling when you remember something looking at a photograph, but the surroundings are foggy. His recent foray into digital collages using scans of physical objects leads to new layers in his work. This experimental layering plays with the relationship between photographic processes, alteration, and memory. They make us question the truth and stories we tell ourselves.

Dillon Bryant (b. Spearfish, SD) is a queer artist and photographer currently based out of the upper American Midwest whose practice explores construction of home, desire, family mythologies, and the Western landscape through collage. Bryant has exhibited across the United States and abroad, appearing in shows at the South Dakota Art Museum, the Washington Pavilion of Arts and Sciences, the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art, the Czong Institute for Contemporary Art, and Filter Space. Bryant holds a BFA from the University of South Dakota and has taken graduate courses at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

You can follow Dillon on Instagram at: @illo.b

From There to Here and Never Back Again

New Lands!

Hope reborn in the souls of men with souls.

Hardship suffered for freedom from hardships.

Faith in God deepened as the living passed the dead.

New lands-

New hopes-

A new nation impatient to be developed

And thirsting more than faith to quench its thirst.

-forward in “These Hills are Yours” by Edward Sundberg, 1952

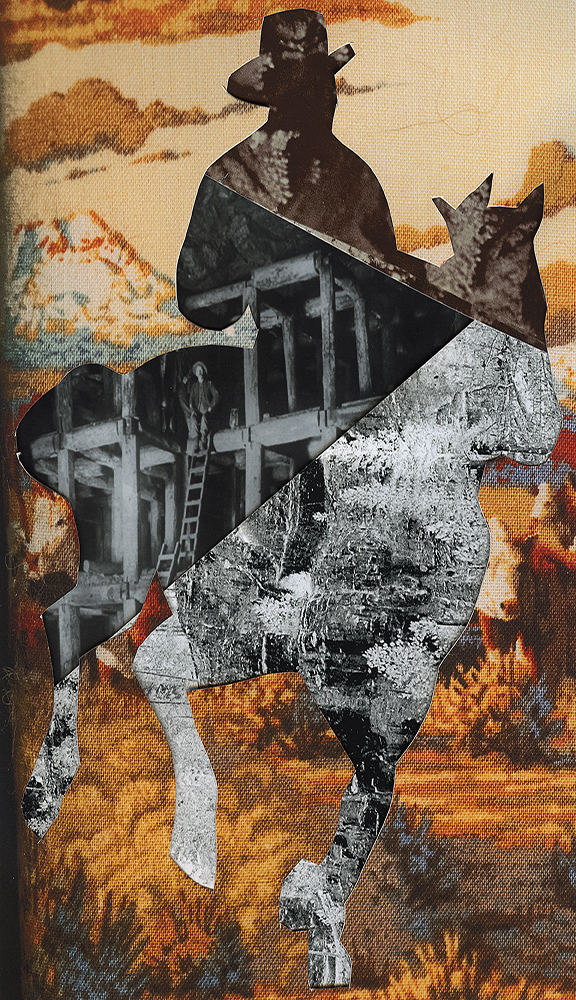

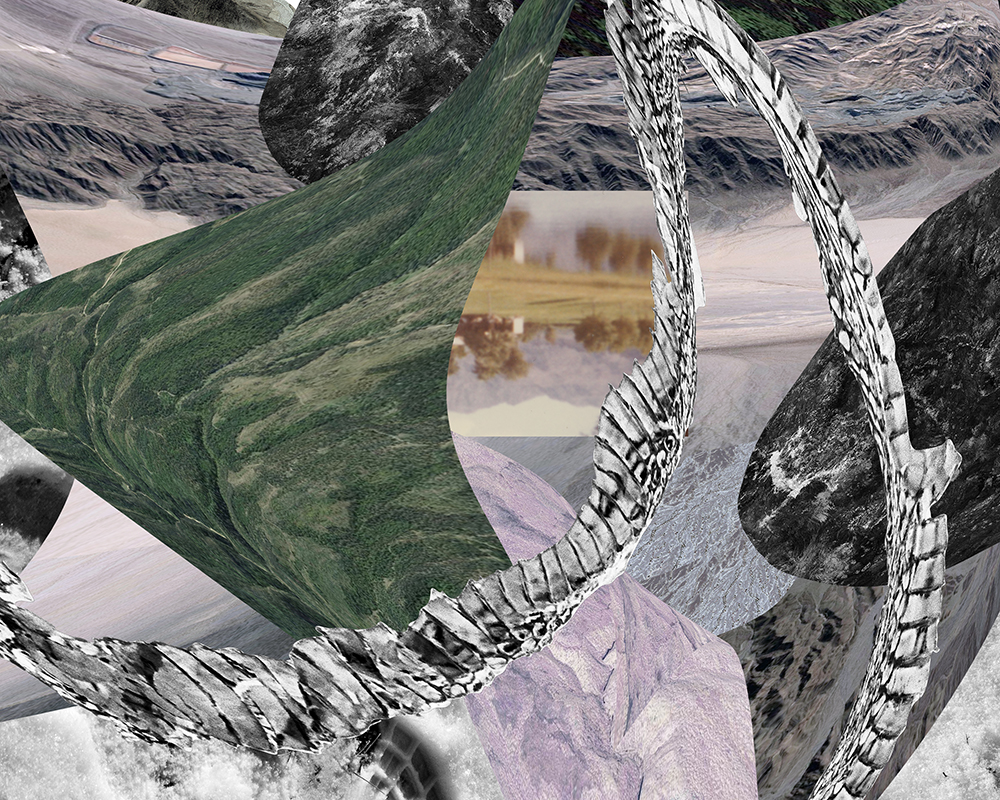

My practice explores constructions of home, desire, family mythologies, and the landscape in relation to the LGBT+ experience through collage and photography. Taken and found images sourced from family albums, maps, guide books, magazines, and other archives are reorientated to examine the legacies of western expansion and mining in the American West with focus on sites in South Dakota (SD) and California. Collage deconstructs and queers the arranged scenes of found images and assembling pieces by hand references the labor of space building. The consciously constructed nature of these collages and images calls attention to the photograph as an arranged object.

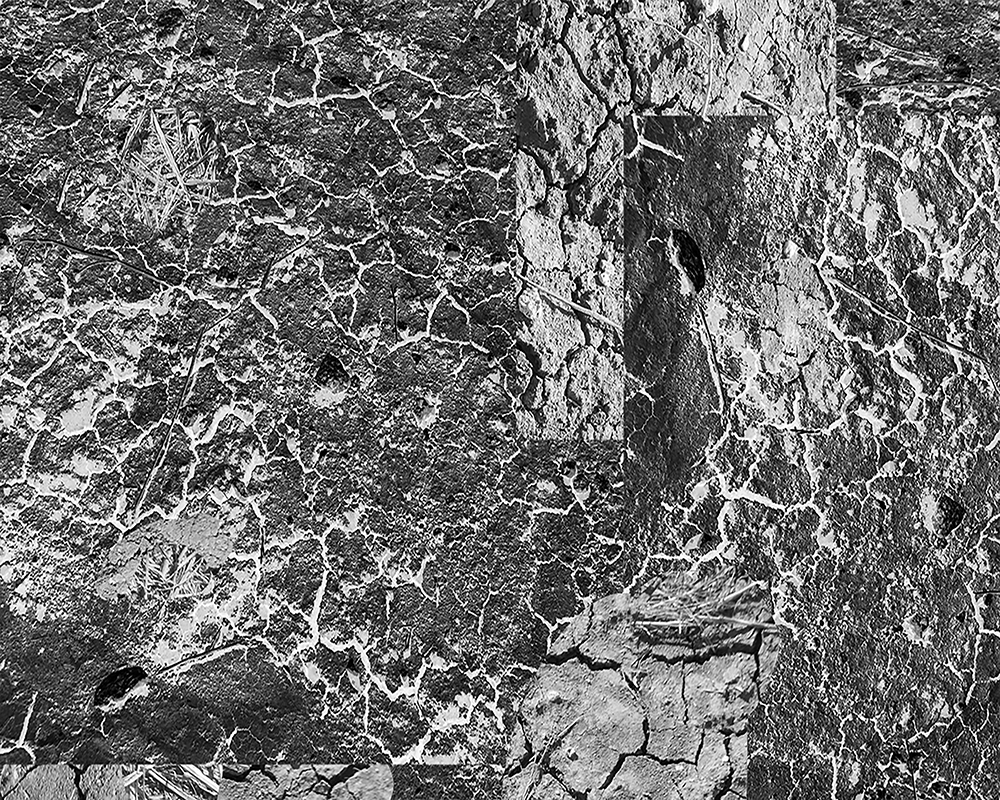

The Black Hills of SD and the Colorado Desert, are contentious spaces. The Black Hills are an occupied landscape that have been embroiled in land sovereignty issues before prospectors discovered gold in the region’s gulches in the 19th century. They are the traditional and sacred lands of the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Arapaho, Crow, Arikara, Pawnee, and the Oceti Sakowin peoples. California’s Colorado Desert is the homelands of the Cahuilla, Gabrielino, Serrano, Luise-o, Chemehuevi, and the Mojavi that were similarly displaced due to settler expansion. The pursuit of mineral resources has shaped popular conceptions of the American West.

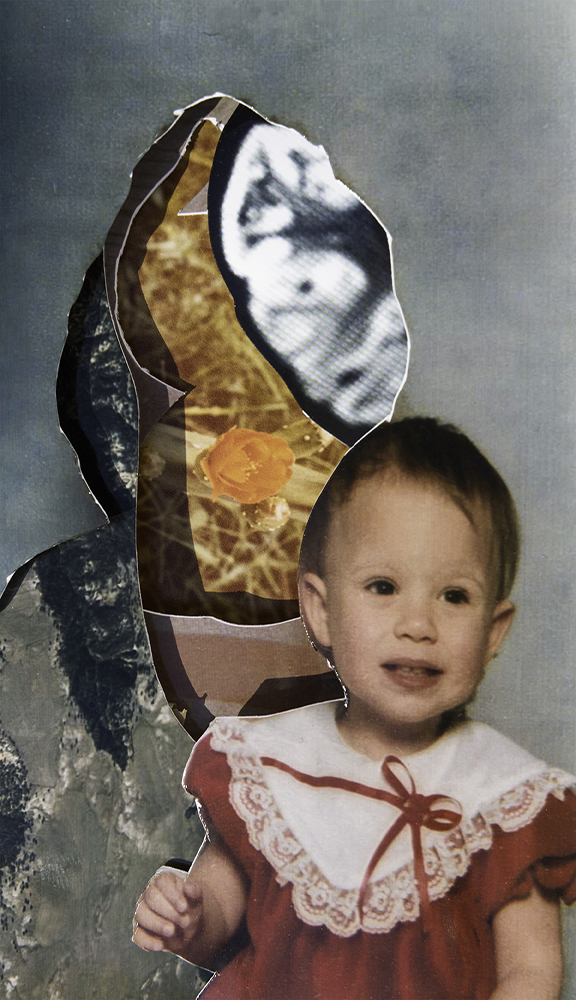

The turn in focus to my family’s round trip migration from SD to California stems from recent family tragedies. In May 2022, my mother suffered a catastrophic and fatal stroke. My mother’s family was born and raised in Eagle Mountain, a mining community in California’s Colorado Desert. Within the span of a generation, the ore veins dried up and the town was abandoned in the 1980’s. The Black Hills share a similar mining history and until its closure in 2002, housed the Homestake Mine, one of the most productive gold mines in the Western Hemisphere. My perception of California and the West is informed through images as I have never been to California. With my mother’s passing, my connection to this part of my family’s history is severed.

I use cameras and scanners to redocument and digitize images and cut pieces to create multiples from which I manipulate and layer into constructed images. Scanners and cameras in archival contexts are tools employed to preserve media and I attempt to queer this function by introducing my hand and other visual glitches by manipulating materials while they operate and in post-production editing. Fixing the collages in this way without adhesive glues and tapes suggest the ephemerality of memory.

©Dillon Bryant, Coachella, Scanned collage made from found images, children’s drawings from Eagle Mountain Middle School (1967), 2022

Epiphany Knedler: How did your project come about?

Dillon Bryant: The genesis of this project occurred while I was visiting my family in the Black Hills over the winter break of 2021. I was staying at my grandfather’s empty house in Spearfish over the holidays and the house is like a time capsule from before the time he passed away in 2019. His furniture, decorations, photographs… nearly everything is where he left it. The house contains so many records of my family’s life in California.

I was going through the basement looking for photo albums when I uncovered a cassette of slides documenting an art project his 6th grade class made at Eagle Mountain Middle School in 1967. Eagle Mountain was a small mining town in Southern California that was abandoned in the 1980’s once the ore ran out. My grandparents and their children witnessed the rise and fall of this community. They returned to the Black Hills shortly after Eagle Mountain became a ghost town.

Growing up, I felt a sense of estrangement from my family growing up queer in a very conservative, traditional area. As a result, I knew very little about my grandfather unfortunately. I know even less about my family’s life in California- I still have not been. Finding these slides was like uncovering a connection to a side of my grandfather I did not know existed. While the project has not fully integrated these slides into the work yet, the impact they had is still important for me to acknowledge.

EK: Do you manipulate the images in any way? Why or why not?

DB: Manipulation occurs at all steps of my workflow and it is something I am recently more thoughtfully engaging with. Previously, I was committed to “faithfully” reproducing the objects and found images out of a sense of respect to my family but I felt creatively stuck. I felt more comfortable experimenting with copies, a reproduction is a reproduction after all. What is most exciting for me is the moment where I am able to cut into the images and layer prints and pieces together. How these arrangements are fixed, being photographed, scanned, or with adhesives affects the final image. I am particularly interested in the flattening that occurs when collages are photographed or scanned. My methodology has changed as a result of the lack of access to printers since I have left school and I have had to move digitally. Post-production offers new opportunities for manipulation as well as the ability to make more instant cuts with quick and pen selections through Photoshop.

EK: Can you tell us about your artistic practice?

DB: I spend a lot of time scouring albums and archives, both digital and physical. I also conduct research on the locations that are depicted in the images as well as trying to learn from those who are familiar with the images themselves. This has become a source of heartbreak as my family has shrunk so much recently with the passing of my grandfather, aunt, and mother over the span of 3 years. My grandfather’s house has become a house of the dead.

When I have a critical mass of images accumulated, I begin making cuts and layers to turn into collages that will either be photographed or scanned. Having the collages exist not as physically fixed objects interests me because it speaks to how ephemeral knowledge and memory are. In archival contexts, a physical object offers the chance to make reproductions while still keeping the original intact. Digital files are anxious and fragile, carrying the risk of degradation and becoming lost.

I am still articulating what the void means in my practice. Photography and images play a key role in how information is shared in our world. Tension is created when visual information is redacted. It speaks to both the impossibility of understanding an archive and its gaps. The void provides privacy for its subjects as well as opportunities for speculative alternatives and excavations.

There is a story about a relative of mine that continues to influence how I work with and think about the archive. In the 90’s when the last of my family was returning to SD from California, my uncle was driving through Wyoming when a blizzard struck and he became stranded. He would succumb to the cold. He has become a legendary figure in my family and his passing continues to reverberate still. My grandfather dedicated an entire room in his house in his memory even.

Thinking more directly about this mythology, I have been experimenting with submerging and freezing images in ice. This intervention directly links to this event but also to the photographic act where time is frozen. In everyday contexts, objects are generally frozen for preservation. They can be thawed for later retrieval. Information can (hopefully) be found again. The ice acts as a temporary screen, clouding parts of the image. The physical cutting of information speaks to the challenges of coming to terms with what is lost. Winters in South Dakota tend to bitterly overstay their welcome but it will provide plenty of time to experiment.

©Dillon Bryant, Family Mythology (Matthew), Documentation of submerged and frozen photograph with void, 2023

EK: What’s your relationship to the found photo? How you come up with stories or meanings with these images?

DB: My relationship to the found images is often mediated through some familiarity with their subject matter, if it’s a family archive or images relevant to a location I am researching. I definitely have a romantic sentiment that influences how I work and I believe we all have this desire to know where we come from. Growing up estranged from my family as a queer person and having family members coming and going constantly, it sometimes felt like I was surrounded more by strangers than relatives. With found images, it becomes easier to project a certain ideology onto them that would be lost if they were more concretely fixed. Collage is so special and vital to my practice because the process takes in the raw material of the world and allows you to create an alternative.

©Dillon Bryant, Desert Pieta, Scanned collage made from found and taken images, children’s drawings from Eagle Mountain Middle School (1967), construction paper 2022

Epiphany Knedler is an imagemaker sharing stories of American life. Using Midwestern aesthetics, she creates images and installations exploring histories. She is based in Aberdeen, South Dakota serving as an Adjunct Instructor and freelancer. Her work has been exhibited with Lenscratch, Dek Unu Arts, F-Stop Magazine, and Photolucida Critical Mass. She is the co-founder of MidwestNice Art.

Follow Epiphany Knedler on Instagram: @epiphanysk

Posts on Lenscratch may not be reproduced without the permission of the Lenscratch staff and the photographer.

Recommended

-

Time Travelers: Photographs from the Gayle Greenhill Collection at MOMADecember 28th, 2025

-

Photography Educator: Juan OrrantiaDecember 19th, 2025

-

Bill Armstrong: All A Blur: Photographs from the Infinity SeriesNovember 17th, 2025

-

Rebecca Sexton Larson: The PorchApril 28th, 2025

-

Matthew Cronin: DwellingApril 9th, 2025